- Login

- Home

- About the Initiative

-

Curricular Resources

- Topical Index of Curriculum Units

- View Topical Index of Curriculum Units

- Search Curricular Resources

- View Volumes of Curriculum Units from National Seminars

- Find Curriculum Units Written in Seminars Led by Yale Faculty

- Find Curriculum Units Written by Teachers in National Seminars

- Browse Curriculum Units Developed in Teachers Institutes

- On Common Ground

- Publications

- League of Institutes

- Video Programs

- Contact

Have a suggestion to improve this page?

To leave a general comment about our Web site, please click here

Diverse Journeys - Americans All!

byWaltrina D. Kirkland-MullinsMy curriculum unit, Diverse Journeys – Americans All! will allow students to grasp the complex concept of being a United States citizen via birthright or through the naturalization process. Students will:

- speculate about and subsequently define what it is to be an American;

- explore different ways diverse people arrived to American shores bringing with them varied cultures and traditions;

- define the terms "immigration" and "naturalization";

- evaluate whether in the past all inhabitants within America's shores arrived via immigration, and if not, to debate whether those who did not immigrate should be considered American;

- define the rights and responsibilities of United States citizens today; and

- based on their own terms, realities, and courses of study, delineate what it means to be American.

By way of student-generated inquiry, family interviews, research projects, viewed films and subsequent story creations shared with the school community, young researchers will gain a deep understanding of American citizenship. Using select non-fictional and realistic fiction resources, young learners will strengthen reading and reading comprehension skills, synthesizing important information to make text-to-world connections, thus deepening their understanding of the subject at hand. Most important, students will come to recognize that irrespective of the journey, diverse groups of people born or naturalized in the United States constitute the American mosaic.

Through its implementation, it is hoped that Diverse Journeys-Americans All! will encourage students to embrace diversity and the unique contributions made by diverse cultures to American society.

Getting Started – Establishing the Tone

During first six weeks of the school year, I set the tone to create an engaging, culturally-inclusive classroom environment. I make every effort to collect and have on hand a wide selection of reading materials. These children's book resources—written across genre and abilities levels—reflect the represented cultures within our school and my specific classroom population. To the best of my ability, I canvass these materials to identify biased or stereotypical wording. I check the copyright date: if resources pre-date the early 70s, I place them to the side or strategically consider how to use these materials to counter misconceptions, as children's books created before this period often contain stereotypical concepts and/or images. I also make it a point to familiarize myself with the customs and mores of key cultures represented in my class. I want to ensure that when my students and their parents set foot in our learning space, they come to realize it is a classroom environment that embraces all. I make it a point to make use of key words of welcome when I meet and greet my students: Ni hao, hola, koninchiwa, kedu, an-nyong hasao, shalom, namaste, wo ho te sen, bon jour, olá, guten tag.... Needless to say, my use of salutations in diverse languages has significantly expanded. In time, however, my students come to understand and make use of these convivial greetings as well. In this way, the door to embracing one another as a microcosm of the American community is opened.

Defining Moments

Within the first week of school, our class jumps right into determining what it means to live and work in a classroom community and to be a classroom citizen. We define the term "community" and collectively decide that it is a group of people who live, work, and/or are situated in the same region. We too define "citizen" and establish that the word refers to one who is a permanent resident and rightfully resides in a country because he or she was either born or legally accepted within a designated community. The children soon agree that they are citizens within our classroom community because they were born in America and legally have a right to be in our school and our classroom.

Having established this foundation, I ask, "Do you think citizens have any special role to play within a given community? Do you have a role to play in our classroom community?" I give the children a few minutes to gather in small groups to brainstorm. Shortly thereafter, my children agree that classroom citizens need to establish class rules that include academic and behavioral standards. They additionally agree that classroom citizens should know, embrace, and strive to follow rules. (My third graders are a tough bunch: they often assert that the consequences for not doing so should be etched in stone—unless THEY have perpetrated the infraction).

We continue our discussion and subsequently create a Classroom Compact, a collaboratively agreed upon listing of do's and don'ts that coincide with our school's overall academic and behavioral philosophy. The children create and sing songs that embrace those rules. We take it a step further: to get a feel for the writing ability and oral communication skills of my young learners, I introduce a writing exercise to have them think about and record academic and behavioral expectations for themselves as being third graders. With pencil and paper in hand, each child creates a biographic snapshot. Upon completion of the first draft, each child is given the opportunity to share their work with one another. Onlookers listen attentively as each peer reads aloud to spotlight themselves and the positive behavior and social interaction they intend to live out in our classroom, deepening our relationship and understanding of one another.

By the end of the first week, my students understand that ours is a classroom community filled with diversity. We move on into broadening that concept. As part of our introduction to Social Studies, we sing and revisit the words to several patriotic songs (e.g., America, My Country 'Tis of Thee, The Star Spangled Banner...) and know each word in the Pledge of Allegiance. Although many of my students can belt out the melodies and have memorized the wording, they have not delved into the significance of their meaning. Using oversized chart paper, we list key vocabulary imbedded within each selection (e.g., allegiance, indivisible, justice, liberty, nation, pledge, pilgrim, republic...) to determine their meaning and ultimately embrace their significance.

Through these strategically planned interactions, my students sense that they are all citizens and an integral part of our classroom community. The children catch on, noting that the classroom is like a miniature world. I introduce the term "microcosm" and reinforce that we can consider ourselves a microcosm of our nation. Diverse groups of people—Americans all.

A Major Question Posed

The meaning of being a classroom citizen having been established, we broaden our scope: "Are you an American citizen? If so, how do you know?" Once again, I disperse my students into small groups and provide an opportunity for them to brainstorm and share their conjectures. Hands raised, they eagerly and almost unanimously clamor, "BECAUSE WE WERE BORN IN THIS COUNTRY!" I share that although this reality holds true for many like themselves, not everyone is born in the United States. Those who are not born here must undergo a particular process to become a citizen. Thus, the door is opened for our learning adventure to begin.

Provide Background Info

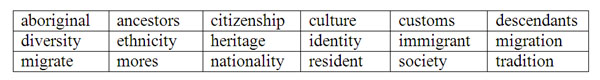

Before introducing supportive, historical background information, assess what the children already know by using a K-W-L chart. Generally ask them to define what it means to be American. Record student responses on oversized chart paper for future reference and review purposes. Subsequently, familiarize students with key terms they will encounter in their course of study:

Note that specific terms such as race, ethnicity, nationality, customs, mores, nationality, and tradition can prove complex and theoretical for young learners. Clarify these definitions through the use of open-ended discussion, role play, and related activities. In time, students will learn to understand these concepts. For starters, however, emphasize that race is a categorization of people into large, distinct groupings based on geographic ancestry, physical characteristics coupled with different and/or similar biological traits. Race is usually classified in color-coded ways, i.e., black, red, yellow, brown, white, respectively representing people of African descent, aboriginal American, Asian, Latino/Hispanic, and people of European ancestry. Highlight that ethnicity implies people identify with one another based on a shared, common heritage, language, or religion (like when we see specific ethnic groups convene to participate in culturally specific festivals and parades). Idealistically, nationality implies that an individual belongs to a nation that shares a common ethnic, language, and cultural identity. (The United States is a complex nation in that it is a heterogeneous society in which not all citizens claim to share a common lineage.)

Culture represents behaviors and beliefs indicative of a particular social, ethnic, or age group (like sitting at a dinner table and waiting for the elder in the family to say grace before the family begins the meal). Customs represent traditional practices embraced by groups of people in a particular way (like celebrating Christmas, Hanukkah, Eid, or Kwanzaa), and mores signify the habitual practices and moral values they accept and follow (like being mindful of elders or nurturing children in one's family and community).

Additionally, clarify the terms "emigrant," that implies an individual has departed from his or her original homeland to settle in a new country or region) and "immigrant," that connotes an individual has come to a new country seeking permanent residency. By introducing such terminology, we empower young learners to enhance vocabulary and make text-to-self-to-world connections as the implemented unit progresses.

Gathering Info/Digging Deep

To rouse curiosity, inform your students that they are about to undertake a grand adventure into the past. To achieve this end, they will stand in the shoes of a researcher, except that they will delve into historical and realistic fiction literature to conduct their exploration.

Introduce the world map. Review its purpose and technical aspects, highlighting directionality and territorial classifications. Point out continental land masses and introduce geographic terminology. Emphasize that somewhere in our genealogy, many of us are the descendants of people who once hailed from one or more of these represented lands. Europeans came from Europe; African peoples were dispersed from Africa, aboriginal Americans resided in both North and South America. Asia, the largest continent, spans from what we today all the Middle East through the Philippine isles; diverse groups of Asiatic people hail from this region. The Aborigines, the original inhabitants of Australia, and others from as far as Europe and Asia, reside on this, the smallest continent.

Follow up by sharing that America is a unique land in that people from diverse cultures live within its shores. Sundry people... Hopeful, thriving, laboring people... Generations of people who in some way contributed to the growth of this nation. The "splash-of-seasoning-accompaniment" we affix to the label American (i.e., African-American, Italian-American, Haitian-American Irish-American, Korean-American, and the list goes on) is reflective of that human montage. But who and what does it mean to be American?

Emphasize that when we retrace our country's history, we soon recognize that the diversity phenomena found within the United States began centuries ago. We too learn that not all of our country's residents immigrated to this new land—that the nomenclature "American" takes on new significance when the story told is culturally inclusive.

The First Americans

History and contemporary Science reveal that aboriginal populations—who have been disrespectfully and generally labeled red-skinned people and/or Native Americans—migrated to what we refer to as the Americas in three major waves as early as 12,000 years ago. Over the centuries, they spread throughout North, Central, and South America, adapting well to their environment. Those who settled in what today is known as the North American continent flourished, embracing diverse lifestyles based on the terrain on which they resided. For example, during the 14th century, northwestern coastal people had developed hunting communities; elk, deer, antelope, beavers, rabbits, and rodent were favored prey used as sources of food, clothing, utilitarian objects, and shelter. Adept in fishing, they were masters of catching salmon that traveled upstream. They dwelled in major villages situated along the coastline. Houses accommodated extended families, and a social order was well-established. The indigenous inhabitants of the Great Plains region mastered planting maize and hunting bison. A migratory group, they worked as one with the land, hunting, planting, and gathering seed in a cyclical fashion. 1 As late as the 17th century, flourishing aboriginal communities existed on the northeastern shores. For example, when Europeans landed in the regions we today call Virginia and New England, adept indigenous peoples had already established a thriving culture and communities and resided therein. 2 Ultimately, Native American people inhabited North American shores long before the arrival of European explorers and settlers.

The Arrival of Blackfolk – A Clarification

The first blacks to set foot on American soil were not all enslaved Africans. Some were members of seafaring crews. Jan Rodrigues, a black sailor and free black man for example, arrived on Manhattan Island in 1613, six years before the first group of slaves were brought to the Jamestown Colony. Some worked as indentured servants, residing under the same grueling living and work conditions as indentured whites. Around 1634, Mathias de Sousa, another individual of African descent, labored as an indentured servant. After having worked for four years in this capacity, he was granted his freedom. A freeman, de Sousa enjoyed the rights and responsibilities held by white counterparts. This free black man was among the original black settlers in what we today call Maryland. 3 Thus, although a vast majority of Africans brought to the New World were enslaved, it is a misconception to believe that all African people brought to America were in bondage.

It is also a misconceived notion that the importation of Blacks to the Americas was rooted in the Jamestown colony in the North American south. In fact, the overall enslavement of black people in the Americas began in the pacific coastal regions of South America in what we today call Columbia and Peru. (During the mid-1500s, Spanish slave traders used Africans and aboriginal Americans to mine silver in Peru. Other blacks were transported to Mexican mines. By 1570, African slaves were brought to Brazil by Portuguese slave traders, forced to cultivate revenue producing sugar plantations. During the 1600s, Spanish, French, Dutch, and Portuguese colonizers used black laborers in the cultivation of sugar and tobacco plantations, producing unimaginable empires for these European nations.)

The African slave trade was a full century old before the trade began in what we today call the United States. In 1619, twenty Angolans were brought to the Jamestown colony. Eight years later, the Dutch West India Company delivered the first load of Angolans to New Amsterdam—today known as New York City. Enslaved blacks were used to clear land, cut timber, build houses, plant crops, and ultimately produce empires for white businessmen. Black human cargo was brought to the American colony as a result of a struggle between the English, Dutch, and Portugal for the control of the lucrative trade. By 1697, the Dutch began bringing slaves directly from Africa to the Americas; like coveted consumer products, blacks were imported across the Atlantic to boost sales and the "new American economy". 4

Incredibly, 12.5 million Africans were shipped to the New World between 1501 and 1866. Fifteen per cent died in the Middle Passage, the dehumanizing slave ship route across the Atlantic Ocean, between Africa and the shores of the Americas. More than approximately 11 million Africans survived the odious journey. Fewer than half a million—i.e., 450,000 blacks shipped from Africa to the U.S. during the trans-Atlantic slave trade—were held in bondage within the United States. In this new homeland, blacks from across the Africa Diaspora were sold and forced to labor in coffee, tobacco, cocoa, cotton and sugar plantations, gold and silver mines, and rice fields. They worked in the construction industry, building homes and cutting timber for ships. They built housing for the master and others. They labored as house servants and were bred for future economic gain. 5 Although they now dwelled in America, people of African descent did not reap the fruits of liberty in this Land of the Free.

The First Processing Center?

The slave trade increased tremendously in the colonies during the 17th and 18th centuries. Blacks were brought into the United States not only to tend the fields harvesting cotton and tobacco, but to cultivate rice plantations in the South Carolinian region. Between the early 1700s through 1799, Charleston, South Carolina, became one of the major slave ports in North America. Many blacks brought into this locale hailed from rice-growing communities like the Senegambias. Their agrarian abilities proved advantageous for southern landowners, further enhancing the lucrative trade of human cargo. 6

Many slave ships that arrived to North America first took port on Sullivan's Island, a barrier isle on the north side of Charleston Harbor. At this South Carolinian site, passengers and crewmembers were held in quarantine, detained either aboard the slave vessel or on board the island from as long as ten to forty days. Crew members and the enslaved alike were scrutinized because the sailing vessels that housed them were often wrecked with infectious diseases like cholera, smallpox, and measles. In time, healthy passengers were released, with able-bodied blacks being processed and sold to fulfill the needs of supply and demand. Ironically, African people had been isolated, examined, and screened before being able to set foot on American soil, a process that would be experienced by countless numbers of immigrant newcomers in future decades. Thus, Sullivan's Island served as a processing center for "African newcomers;" the only exception is that these new arrivals came not of their own volition, but rather as shackled merchandise sold to the highest bidder. 7

European Immigration

In the early North American English colonies, countless numbers of immigrants set out from European shores to flee religious and/or political persecution. Some who had already settled in the American colonies needed workers to help cultivate the land. They offered incentives to bring in white indentured servants to fill this need. Many trustworthy and diligent laborers were hired. Oftentimes, they were duped into working as tradesmen in a new land for established periods of time, after which they would be given parcels of land. Many convicts were brought over from Britain; thieves, thugs, robbers, and rapists were among those sent to labor in the American colonies.

Many who came over between the sixteen and seventeen hundreds risked their lives to leave homelands wrought with poverty and crime; upon arriving in the early American colonies, as in Jamestown and Maryland plantations, many European immigrants worked under deplorable conditions as indentured servants. 8 Between 1760 through 1775, waves from the British Isles flooded North America. Protestant Irish, Scots, Swiss, and German-speaking immigrants stretched across the New England region, spreading out to Pennsylvania down towards Virginia and beyond. With the influx of diverse European groups came differences in religious practices and social status. The need for colonial labor, however, often outweighed those differences. As a result, established British settlers tended to ignore differences among particular groups of European newcomers, and many European immigrants found America to be more tolerable than their original homelands. 9

Between the early-to-mid-1800s through the 1920s, 23 million immigrants had sailed across the Atlantic, crammed in huge sailing vessels with the hopes of residing in the United States. Many traveled from southern and eastern Europe fleeing everything from famine and homelessness to economic woes. Some were exiled for having committed crimes in their homeland. Huge numbers, in search of a new land where a better way of life was deemed possible, stepped out on faith to make the journey. Between the 1930s to mid-60s, the influx of immigrants remained constant. Millions of people continued to come to America's shores. Some came of their own choice in search of beginning new lives; others came to escape the aftermath of war, slavery, political persecution, and famine. 10

Restrictive Surprises

Before the 1800s, it seems there were no limitations on the influx of newcomers to what we today call America. By the early-to-mid 1800s, widespread fear began to set in. Ironically, some people who had already gained citizenship status within our country took on a different view. They observed that communities were rapidly growing, some with residents unlike themselves. They held that many newcomers were impoverished and uneducated. Communities were becoming overcrowded. Living conditions for many were deplorable, and competition for employment was fierce. Because of these societal realities, many former settlers believed the government should limit the number of immigrants seeking entry and citizenship into our country.

For example, during the late 1840s, Roman Catholic Irish arrived in growing numbers. To many native-born Americans, impoverished Irishmen were inundating the cities' poor houses and asylums, having a negative impact on the economy. These points-of-view were not limited to the Irish alone. The Chinese had heavily immigrated to the West Coast during the Gold Rush era, between 1849 and 1862. Like many European immigrants who had previously settled in the region, many Chinese were in search of a better life and economic opportunities. Adept workers, they were used as a source of cheap labor in helping to build the transcontinental railroad. Working at lower wages proved problematic for many whites. Additionally, the countenance of the Chinese differed significantly from their Irish, German, and British counterparts. Repeatedly at the brunt end of racial slurs, they were often targeted because of their physical appearance. In time, Chinese immigration was banned; restrictive measures were set in place beginning with the Chinese Exclusion Act. 11

The Chinese Exclusion Act was passed into law by the U.S. Congress and signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882. The Chinese Exclusion Act was the first significant law that restricted immigration of a specific ethnic group into the United States. Although not overtly asserted, it can be deduced that race and ethnicity served as a contributing factor in the government's enacting this legislation. Interestingly, this Act proved a restrictive measure not only to the Chinese. It restricted working-class ethnic groups from immigrating to the United States: those newcomers included the Japanese, Filipinos, and myriad individuals hailing from Asian nations.

In response to increasing public opinion, Congress continued to create laws that limited the number of immigrants who could enter the United States from any particular nation. One of those laws was the Quota Act of 1921; it drastically impacted the admission of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe to our country. Additional quotas were enacted by the government: in 1924, laws were passed to counter the influx of massive immigration by Italians, Poles, Hungarians, and other European immigrants. They, too, were discriminatory in nature in that they were established based on the individual's national, religious, and ethnic background. Supposedly, immigration quotas correlated with race and ethnicity were revised and abolished in 1965. Immigration, however, continues to be a major political debate in the 21st century. 12

Processing Centers, Too!

By January 1, 1892, Ellis Island was established and served as the primary immigrant processing center for our nation. From 1892 through 1954, more than 12 million immigrants were processed through this port of entry. New arrivals underwent intense questioning and examination within the facility before being allowed to enter the country; this process was labeled naturalization. Many immigrants referred to Ellis Island as "Heartbreak Island" because of the dehumanizing interrogation processes experienced to be eligible to become an American citizen.

Similar "holding pens" existed along the west coast of America: Angel Island, a triangular land mass located in San Francisco Bay, California, was one of those sites. In 1910, legislation was passed to use it as an immigration processing site for the anticipated influx of European newcomers with based on the threat of World War I. The expected European surge never occurred; instead, a flood of Asian immigrants ensued. 13 The United States did not have a secure way of identifying or confirming whether newcomers were related to Chinese Americans who already resided in the U.S. As a "precautionary measure," immigrants were forced to reside on Angel Island for up to six weeks with no guarantee of entry. Families housed therein were isolated and incurred deplorable conditions. They never expected their dream of America to take such an unexpected turn.

It is hard to believe that many of us—descendants of these diverse cultures—reside in the United States today because of past ancestral journeys, but it is true. In time, newcomers became residents and residents became generations of diverse families born in America.

Related Activity #1: Walk in Their Shoes Journal Insert

Time Frame: Weeks 3 and 5 (3 days a week, 50 minutes per session)

Objective: To have students read select immigrant narratives. Subsequently, have them brainstorm and answer questions to demonstrate understanding of text; describe the character traits; define the experiences, motivations, and emotions of main characters within the text; and explicitly recount key aspects of each story in both oral and written form to demonstrate a thorough understanding of covered subject matter.

Focus Question: How might you have felt about leaving your homeland to begin a new life in an unfamiliar land?

In addition to the above-noted objective, students will make solid text-to-world connections via the implementation of this language-arts/social studies adventure.

Delve into this learning experience by first conducting read-aloud sessions to highlight the background experiences of select immigrants (see bibliographic children's book resource listing). Model and engagingly share a story selection. Have students close their eyes and envision themselves as the immigrant newcomer. What would the experience have entailed? What words best describe the journey? How may the individual have felt traveling from a familiar homeland to distant shores? Encourage students to immerse themselves in the imaginary journey.

Follow up and continue the read-and-share experience by having children delve into similar narratives during independent reading and/or Readers Workshop. Make a wealth of several non-fictional and realistic fiction titles pertaining to immigration experiences in the United States available. Continue to use the previously noted questions as your focus.

Subsequently, have students participate in a related writing activity. Share that they will create an imaginary, memoir-type journal insert placing themselves in the shoes of a select American newcomer. The work must be descriptively written as if you had actually experienced the immigrant's journey. "Show" the experience by using adjectives, adverbs, powerful synonyms for overused words and expressions, idioms, similes, metaphors, onomatopoeia, and other descriptive words. Adhere to the focus question. In this regard, the journal insert must include the homeland from which the individual immigrated, the reason the individual left his/her homeland, the journey specifying traversed oceans and landmasses, and what it felt like arriving in a new land.

Naturalization in the 21st Century

By this part of our unit study, students generally grasp that unless one is born in the United States (or was born abroad with either parent being an American resident at the time of one's birth), newcomers who wish to reside in our country must undergo a special procedure to become a permanent resident. Emphasize that although immigration stations no longer exist in the U.S. as they had in the past, immigrants must still undergo the rigorous naturalization process.

Today, it takes an estimated six months to complete the entire naturalization process. Generally, immigrants must complete an application to apply for citizenship (and, today, the naturalization application can be completed on-line). Candidates for admission must be 18 years old or older and must have lived within America for a minimum of five years, although some exceptions occur. Candidates must be law-biding individuals with good moral character. They must have a basic knowledge of American history and government and must be able to read, write, and communicate in English. If the immigrant candidate has ever been arrested or accused of having committed a crime or has had questionable involvement with anti-American organizations, becoming an American citizen will be impeded. Candidates must undergo physical exams. In addition to this, applicants must pay a naturalization application processing fee, during which time the individual is photographed and fingerprinted.

Candidates for citizenship must additionally pass language tests: they must be able to read fluently and be able to respond to questions in both spoken and written form. The test—administered solely in English—consists of 10 questions pooled from a larger list of 100 questions. Questions asked range from in which month do we vote for the President or what are the opening words of the Constitution to in which year was the Declaration of Independence written or if the President and Vice President can no longer hold office, who will take over?

Test takers are expected to answer 6 out of 10 questions to pass this portion of the exam.

A Worthwhile Process

Although undergoing the naturalization process is time-consuming, it has its advantages: If the candidate for citizenship passes the exam, that person has the right to vote, is qualified to have family members reside within American borders, is able to secure citizenship for children born outside of the U.S., is allowed to travel freely in and out of the country, is permitted to become a federal employee, and is able to collect social security and Medicare benefits. The new citizen is also able to run for a position as an elected official, excluding the Presidency.

Related Activity #3: Have students take a mock, on-line, naturalization multiple choice exam. Emphasize that although the naturalization exam is not administered in multiple-choice form, practicing the Q&A session on this site gives one a sense of what candidates for citizenship must know to pass the test. This activity can be incorporated as a complementary Social Studies Center or Readers Workshop on-line activity. To access, key in http://www.uscis.gov/portal/site/uscis/menuitem. d72b75bdf. Search for the "Citizenship" icon contained therein and hit "The Naturalization Test" label.

Related Activity #4. "Family Time Line" Interview

Time Frame: Weeks 6 and 7 (3 days a week, 50 minutes per session)

Focus Question: Americans have undertaken different journeys to be deemed citizens. What was your family's journey to America? Were they immigrants or American born? How did they come to reside in the city and state in which they currently live? Explain.

Have students interview parents and/or grandparents to determine how they came to live in their current city of residence. Provide parents with an announcement letter to communicate background information regarding the assignment. Clarify that information gathered will be used for a classroom writing exercise in correlation with our study of immigration and what it means to be American. Emphasize that the activity is interdisciplinary in that it (1) allows children to make text-to-world connections regarding our Social Studies unit of study; (2) helps children gain insight into understanding the similarities and differences experienced by diverse cultures, and (3) reinforces the use of logical thinking and oral and written communication skills. Ask that they be supportive in assisting their child in gathering and recording information. Also, falling in line with writing requirements, reinforce that children should record information using complete sentences.

TIME LINE QUESTIONNAIRE

In what country were you originally born? If outside of the U.S., where did you live before you moved to America?

When did you come to the United States?

What mode of transportation did you use to get here?

How did you feel about moving to a new country?

What types of traditions did you and your family embrace before coming to this country? (For example, did women stay home with the children while the men went out to work? Did you have birthday parties and other family celebrations?)

Did you understand and know how to speak English when you moved to the U.S., or did you have to learn the language?

If you had to learn English, was learning the language difficult or easy for you?

What were your first impressions when you arrived at your new country of residence? Did your first experiences live up to what you had hoped for?

What types of traditions did your family embrace after relocating to the U.S.? (Did you continue past traditions? Did you go to church every Sunday, sit at the dinner table to eat meals with your family members, participate in special organizations or community functions...)

What type of work did you do in your homeland before you moved here?

Where did you first settle when you came to this country?

What was the primary reason you moved there?

What was the final city in which you and your family resided in the U.S.? How did you come to live there? Was relocating easy or difficult? What was the community like? How did you get here (over land, by boat, by plane)? Were you ever worried or frightened about relocating?

What were your first impressions when you arrived at your new city of residence? Did your first experiences live up to what you had hoped for?

Did you experience any racial or religious prejudice when you moved to this country? What happened?

Subsequently have students write a two-page narrative about their parents' or grandparents' migratory experience, conveying the story as if they were in their family members' shoes.

Tying It All Together

The children have acquired a firm handle on what it means to be American. Based on their study, students will come to agree that the first peoples to dwell in our country are the original Americans, and that Africans brought and forced to reside in our country against their will are also American citizens. They will recognize that immigrants who undergo the naturalization process and descendants born within this nation are deemed American citizens. They too will understand that there are rights and privileges granted those of us who are citizens in this country, that we must be mindful of our rights as residents of the United States.

Foundation lain, revisit their initial K-W-L chart, this time making note of what they originally through as compared to what they have learned. Invite them to create a poetic skit to convey their understanding.

Related Activity #5. "Americans All!" Performance Poetry Creation

Time Frame: Weeks 7 and 8 (3 days a week, 50 minutes per session)

Focus Question: How can we present our understanding of what it is to be an American citizen?

Allow the children to be creative, to think ways to define what it is to be American in the 21st century. Have students share their opinions regarding aspects of American life that serve as indicators in this regards. (I preliminarily canvassed my third graders. They provided their list of indicators asserting that they have the freedom to wear trendy clothes; listen to different types of music; and to eat delicious types of different ethnic foods— including hot dogs and apple pie. They noted that they are free to worship in churches, synagogues, or temples, that they have options to attend private or public schools. They insightfully established that they are free to make choices—that for the good of the community, it is best to make wise ones. Their points of view aligned with Charles R. Smith, Jr.'s poetic work entitled "I Am America." As a result, our class collectively decided that we would to find a way to incorporate this work into their own poetic explanation.)

Preliminary Wheels in Motion

During week seven, have students begin working on the collective poetic writing effort. Have them revisit why people immigrated to America, making note that Native Americans and African slaves are deemed citizens because of the way in which they came to reside in the North America. To be inclusive, have students come up with greetings shared in diverse languages. (My children recommended including twelve salutations representative of languages spoken by students in our school in their poem. They too noted that a Native American greeting should be included as well. In this regard, I volunteered the use of the phrase "ya'at'eeh" based on a salutation I learned from YNI Fellow Barsine Benally, an adept third grade teacher and member of the Dine Nation [more commonly but inaccurately referred to as the Navajo people] in Arizona; the greeting means "all is well today." Ecstatic, my students also thought it best that some students dress up in traditional clothing reflective of aspects of the diversity represented in our classroom and school overall.)

Although we have not yet implemented our poetic production, I envision my students being strategically situated on stage, making their debut before the entire school body in our school's performance space during the first quarter of the upcoming school year. If our proposed presentation cannot be held in the performance space, the gymnasium or school auditorium will serve as an equally appropriate venue. Microphones in place, each student—using poise and prosody—will engagingly recite his or her part.

In the interim, my class has collaboratively worked on the poetic portion of their presentation as follows:

Ya'at'eeh! Hola! Bon jour! Kedu! Namasta! Hello!

We are citizens. Americans all!

We have different styles. Different ways.

Different languages, but we all can say

We live in this great nation filled with diversity.

A great mosaic—descendants in this homeland of the free.

Many of our ancestors were born first in this land

Thriving on this continent before conquests began.

Many of our ancestors traveled across the sea

In search of new beginnings and hope-filled destinies

Some sought religious freedom, some fled poverty and strife

Some came because of famine—starvation was their plight

Some came because of hopes of wealth, some came because of greed

Many were brought in yokes and chains

For others' material needs

No matter what our journey, our lives intertwined

Many helped to build this nation—this country, yours and mine!

Shalom! As-salaam alaikum! Ni hao! An-nyong! Hello!

We are citizens. Americans all!

At this point, my students will jump right in to Charles Smith's work, beginning with the lines "I am proud... I am diverse...soft-spoken and loud..." until the author's entire poetic creation is completed.

Conclusion

Learning about America's past history and the experiences of its people truly helps us understand the complexity of our country as an American community. Introducing this reality to children at a young age helps to lay the foundation for learning to embrace one another across cultural and racial differences. Putting the accent on our similarities through interconnected life experiences will help us begin to embrace one another as members of a nation united. My third graders have demonstrated that they are well on their way to embracing the American Mosaic—setting the tone to help create a more inclusive America today and in years to come!

Supplemental Activities: These fun-filled excursions are worth the trek:

Statue of Liberty - Ellis Island Immigration Museum. Have children experience an imaginary journey by taking an excursion to this historic landmark. Children will take the Staten Island Ferry across to this historic landmark. Contact groupsstatuecruises.com for group sales booking information.

Can't visit in person: take a virtual tour by visiting Scholastic, Inc website http://teacher.scholastic.com/activities/immigration/tour/stop1.htm

The American Museum of Natural History in New York City

("Suggested" General Admission applies – for additional information, contact (212) 769-5250):

The Hall of Human Origins and Cultures. Children will gain insight into the lives of people from past civilizations across cultures that existed centuries ago.

The Rose Center for Earth and Space. Particularly visit the Pangaea display; have students speculate how people and/or wildlife came to exist in the seven continents.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

TEACHER RESOURCES

Carson, Benjamin. America The Beautiful: Rediscovering What Made This Country Great. Zondervan Press (2012). A different spin on an often-revisited-and-rehashed topic.

Bailyn, Bernard. Voyagers to the West: A Passage in the Peopling of America on the Eve of the Revolution. Vintage Books, New York (March 1988). A primary source of background info re: European colonization and immigration in North America.

Dublin, Thomas. Immigrant Voices: New Lives in America, 1773 - 1986. Vintage Books, New York (1988). University of Illinois Press (1993). Provides insight into the immigration process as seen through the eyes of Russian, Puerto Rican, Italian, Vietnamese, Mexican, and other diverse newcomers to American shores.

Franklin, John Hope. From Slavery to Freedom. Vintage Books, New York (1992). This work provides an objective look at the Africa Diaspora, beginning with great empires of Africa through the slave trade up until the African's fight for freedom during the slave trade and beyond.

Collins, Editor, Richard. The Native Americans: The Indigenous People of North America. Created in affiliation with the Smithsonian Institute and the American Museum of Natural History, and Yale Ethno-anthropologist William C. Sturtevant, this work provides a wealth of background information regarding Americas original indigenous inhabitants.

Daniels, Roger. Coming to America. Second Edition: A History of Immigration and Enthnicity in American Life. Harper Perennial, New York (October 2002). Provides primary resource info and theoretical reasoning behind immigration.

(2002).Feelings, Tom Middle Passage - Introduction by Dr. John Henrik Clarke, (1995). A pictorial essay of the dehumanizing journey; browse carefully through work to determine age-appropriate illustrations for classroom use.

Gates, Jr., Henry Louis. Life Upon These Shores: Looking at African American History. A primary source of background information regarding African American Heritage, beginning from pre-slavery to the 21st century.

Manning, Marable and Leith Mullings, (Editors). Let Nobody Turn Us Around. A revealing anthology of collected works and primary source documents from civil rights leaders and activists; takes a look into American History from slavery to the 20th century through the lives and experiences of those of African descent.

Mannix, Daniel P. Black Cargoes: A History of the Atlantic Slave Trade 1518 -1865. Viking Press, New York (1978). Contains true accounts of the trafficking of African human cargo as experienced by white colonists and slave traders.

Reimers, David M. Unwelcome Strangers: American Identity and the Turn Against Immigration. Columbia University Press, New York (1999). A primary resource regarding immigration from Pre-World War II and onward, immigration policy, restrictionist views, and related debates.

Smith, James and Edmonston, Barry, et al. The New Americans: Economic, Demographic, and Fiscal Effects of Immigration. National Academy Press, Washingon, DC (1997). A comprehensive report regarding immigration and immigration issues impacting the U.S. in the 20th century and beyond.

Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. Harper Perennial Modern Classics. New York, ( November 2010). Provides a refreshing, culturally-inclusive account of American History.

STUDENT RESOURCES

Poetry

Adoff, Arnold. Black Is Brown Is Tan. Amistad/Harper-Collins Publishing Company. New York (2003). A poetic look at interracial family/relationships.

___________. All The Colors of the Race. Beechtree Books. New York (March 1992).

Myers, Walter Dean. We Are America: A Tribute from the Heart. Harper Collins, New York (2012). Thought-provoking poetic work that gives insight into immigration journeys of diverse groups of Americans.

Historical/Realistic Fiction

Bunting, Eve. How Many Days to America. Sandpiper Press. (October 1, 1990). Immigration as seen through the eyes of a Haitian refugee family seeking political asylum on American shores.

Choi, Yangsook. The Name Jar. Dragonfly Books, New York (2001). A realistic fiction work that gives a spin on assimilating into American culture, as seen through the eyes of a Korean child, Hunei (pronounced Un-hay).

Kent, Rose. Kimchi & Calamari. Harper Collins Publishers, New York (2007). A moving, realistic fiction work that addresses self-discovery, race and family as it pertains to migration and interracial adoption.

Lee, Millie. Landed. Choi, Yangsook. Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, New York (February 2006). Because of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, entering the United States from China proves challenging for 12-year old Sun. Despite having been accompanied by his father, a naturalized citizen, on the long journey, upon arriving to American shores, Sun is forced to wait for four weeks before undergoing the interrogation process. Sun frets over the possibility of having to return to his homeland, China: a gut-wrenching, often omitted-from-the history-books look at the dehumanizing naturalization process as experienced by Asian immigrants.

Levine, Ellen. I Hate English. Scholastic, Inc. (1989). A sensitive realistic fiction tale about a young immigrant girl from Hong Kong and her struggle to live in two worlds, learning to communicate in two languages.

McGill, Alice. Molly Banneky. Sandpiper, New York. (January 2009). A fiction work ground in historical truth regarding the life of British-born indentured servant Molly Banneker, grandmother to scientist and mathematician Benjamin Banneker.

Saltonstall Carrier, Katrina. Kai's Journey to Gold Mountain: An Angel Island Story. Angel Island Association, Tiburan, California (2005). A historical fiction tale grounded in fact based on the life of Albert Kai Wong regarding the Asian immigrant experience on Angel Island.

Informational

Burns-Knight, Margy. Who Belongs Here? An American Story. Tilbury House, Gardiner, Maine (1993). The tale of a Cambodian immigrant and his encounter with racism upon migrating to American shores. Accompanied by supportive, statistical data, this work is a blend of memoir and supportive non-fictional details highlighting real-life encounters experienced by newcomers to America's shores.

Gordon, Susan. Asian Indians: Recent American Immigrant Series. Franklin Watts (October 1990). Explores aspects of Asian culture, the struggles many Asiatic peoples and their reasons for immigrating to American shores.

Landau, Elaine. Ellis Island, Scholastic Inc., New York, New York (2012). Informational reference resource that takes a vivid look at immigration via this immigration stoppoint.

Mayberry, Jodene. Filipinos: Recent American Immigrant Series, Franklin Watts (October 1990). Explores aspects of East Indian and related cultures, culture, the people's struggles and reasons for immigrating to American shores.

______________. Koreans: Recent American Immigrant Series, Franklin Watts (October 1990). Explores aspects of Korean culture, the people's struggles and reasons for immigrating to American shores.

______________. Chinese: Recent American Immigrant Series (August 1990). Explores aspects of Chinese culture, the people's struggles and reasons for immigrating to American shores.

______________. Eastern Europeans: Recent Immigrant Series (March 1991). Explores aspects Eastern European culture (including displaced persons and Jewish refugees), their struggles and reasons for immigrating North America.

______________. Mexicans: Recent American Immigrant Series (October 1990). Explores aspects of Mexican culture, the people's struggles and reasons for immigrating to American shores.

Freeman, Russell. Immigrant Kids. Penguin Putman Books for Young Readers. Looks at immigration via Ellis Island with the accent on life and socialization experienced by American newcomers to American shores; includes rich black and white photography.

Maestro, Betsy. Coming to America: The Story of Immigration Scholastic, Inc., New York, New York (1999). A child-friendly resource that accentuates real-life issues faced by newcomers to America, i.e., language barriers, culture shock, and cultural/social isolation.

Thompson, Gare. We Came Through Ellis Island: the Immigrant Adventures of Emmar Markowitz. Russian Jews flee religious persecution in their homeland, immigrating to the U.S. for religious/political asylum.

Winter, Max. The Statue of Liberty. Newbridge Educational Publishing, New York (2001). A non-fictional work regarding the origins and creation of the Statue of Liberty.

Yin. Coolies. Philomel Books, New York. Often unheralded view of Chinese emigrants' quest experience re: the 1845–1851 building of the transcontinental railroad system.

ON-LINE RESOURCES

Immigration - Ellis Island: The Journey to America. http://library.thinkquest.org/20619/index.html An on-line overview of the history of immigration provided by the Teach Tolerance organization (accessed May 5, 2012).

http://www.ellisisland.org/genealogy/ellis_island_timeline.asp The Statue of Liberty/Ellis Island Foundation. Ellis Island timeline (accessed June 7, 2012).

http://www.ellisisland.org/genealogy/ellis_island_timeline.asp The Peopling of America. The Statue of Liberty/Ellis Island Foundation. Reveals statistical information regarding the influx of diverse ethnic groups via Ellis Island (accessed July 12, 2012).

http://www.angel-island.com/history.html/ Angel Island: Immigrant Journeys of Chinese Americans. Includes historical essays and photographic images re: Chinese immigrants detained on Angel Island (accessed July 12, 2012).

http://www.aiisf.org/ Angel Island Immigration Foundation official website. Includes virtual tour, contact resources, images of author/illustrator Millie Lee and Yangsook Choi and their recent collaborative effort on behalf of Asian immigrants, and more (accessed June 7, 2012).

http://www.lehigh.edu/~ineng/VirtualAmericana/chineseimmigrationact.html. Background information on the Chinese Exclusion Act (accessed July 13, 2012).

http://www.google.com/search?q=angel+island&hl=en&prmd=imvns&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&ei=CkoDUMLWD4Po6wHJpsDpBg&sqi=2&ved=0CG4QsAQ&biw=1205&bih=602 Angel Island photographic images (accessed July 15, 2012).

http://sun.menloschool.org/~mbrody/ushistory/angel/human_history/ A historical view of the island and activities occurring thereon. (accessed July 10, 2012).

The Human Face of Immigration. http://www.tolerance.org/magazine/number-39-spring-2011/human-face-immigration A look at stereotypes and bias regarding immigrant populations (accessed May 5, 2012).

http://www.fordham.edu/academics/colleges__graduate_s/undergraduate_colleg/fordham_college_at_l/special_programs/honors_program/hudsonfulton_celebra/homepage/the_basics_of_nyc/immigration_32224.asp Immigration in New York City, Fordham University Archives (accessed July 15, 2012).

http://www.uscis.gov/portal/site/uscis/menuitem.d72b75bdf98917853423754f526e0aa0/?vgnextoid=afd6618bfe12f210VgnVCM100000082c60RCRD&vgnextchannel=afd6618bfe12f210VgnVCM100000082c60RCRD&print=0 United States Citizenship and Immigration Services Mock Naturalization Self-Test (accessed July 8, 2012).

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/asian_voices/voices_display.cfm?id=25 Digital History: The Chinese Exclusion Act. Highlights background details regarding the 10-year restrictive immigration law targeted at Chinese newcomers (accessed April 20, 2012).

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/asian_voices/voices_display.cfm?id=15 Racism and the law as it pertained to Blacks, Native Americans, Asians Americans and other non-whites as affirmed by the California Supreme Court during the mid 1800s (accessed April 20, 2012).

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/race/ Stanford Encyclopedia on Philosophy: Race. Examines the definition of race from a philosophical and scientific standpoint (accessed May 5, 2012).

http://www.alovelyworld.com A Lovely World Virtual Tour. Visual images of select countries and cities from around the world. Note that this is not an all-inclusive website in that not all countries within our global community are represented (accessed April 20, 2012).

http://www.africanamericancharleston.com/lowcountry.html Background info re: Charleston, South Carolina's Sullivan Island (accessed June 30, 2012).

ADDITIONAL TEACHER RESOURCES

Mondo Non-Fictional Info Pair Resources

Journal of a New Citizen Info Card No. 8B, Grade 3, Level N

Citizenship Q&A Info Card, Grade 3, Level N

APPENDIX OF CURRICULUM STANDARDS

Diverse Journey – Americans All! correlates with the Connecticut Framework K-12 Curricular Goals and Content Standards for Social Studies and Language Arts. Students will be exposed to select children's narratives and poetic works; and scaffolded instruction, students will embrace the following:

Social Studies Curriculum Content Standards 1.5, 1.13, 2a, and 2c. Students will discuss and understand the characteristics and interactions among and across cultures, social systems, and institutions; compare and contrast identities of ethnic/cultural groups; and identify the rights of American citizens in a democratic society.

Language Arts Content Standards 1 (Reading and Responding) and 2 (Producing Texts). Students will describe their thoughts, opinions, and questions that arise as they read and listen to a text; use non-fictional and realistic fiction text structures to predict, construct meaning, and deepen understanding of text to summarize content; identify characters, settings, themes, events, ideas, relationships, and details found within the text; work both individually and on a collaborative basis in collecting and historical info; gather information from a variety of primary and secondary sources including published resources and electronic media to discover non-fictional support info; read/share their creative writings with partners, who will constructively critique the work, highlighting elements in the literary piece that coincide with select topic of study.

Endnotes

- Hurst Thomas, David. The World As It Was – Part 1: The Native Americans – An Illustrated History, pp 32 - 47

- Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States, pp 12-15

- Gates, Jr., Henry Louis. Life Upon These Shores: Looking at African American History 1513-2008, pp 12-13

- Ibid., p 27-29

- Ibid., pp 25-29

- Johnson, Charles and Smith, Patricia. Africans in the Americas: America's Journey through Slavery, pp 77-79

- Charleston's African American Heritage: A Port of Entry for Enslaved Africans. http://www.africanamericancharleston.com/lowcountry.html

- Reimers, David M. Unwelcome Strangers: American Identity and the Turn Against Immigration, pp 5-10

- Ibid., p 8

- The Peopling of America. The Statue of Liberty/Ellis Island Foundation. http://www.ellisisland.org/ genealogy/ellis_island_timeline.asp

- http://www.lehigh.edu/~ineng/VirtualAmericana/chineseimmigrationact.html The Chinese Exclusion Act (1882): Brief Overview. A glimpse at the racially divisive legislation passed by Congress and its impact on Chinese immigration.

- Ibid.

- http://sun.menloschool.org/~mbrody/ushistory/angel/human_history/ General history of Angel Island.

Comments (0)

THANK YOU — your feedback is very important to us! Give Feedback