- Login

- Home

- About the Initiative

-

Curricular Resources

- Topical Index of Curriculum Units

- View Topical Index of Curriculum Units

- Search Curricular Resources

- View Volumes of Curriculum Units from National Seminars

- Find Curriculum Units Written in Seminars Led by Yale Faculty

- Find Curriculum Units Written by Teachers in National Seminars

- Browse Curriculum Units Developed in Teachers Institutes

- On Common Ground

- Publications

- League of Institutes

- Video Programs

- Contact

Have a suggestion to improve this page?

To leave a general comment about our Web site, please click here

Journaling in Nature: Journaling to Improve Observation and Reflection

byChristopher SnyderIntroduction – Why Nature Journaling?

I have always kept a journal, or something to write in or draw in, to keep some sort of track of my daily life, artistic ideas, and feelings. If we were to cross paths, you would probably find me with either a sketchbook or pocket sized journal (at the very least, you will catch me with a folder full of blank or partially drawn-on paper). Most of the time, my entries come out in the form of prose or poetry and never really as a vehicle for intentional daily reflection. Often, my journal entries are not really much more than a formally documented equivalent of writing or drawing on a restaurant napkin. However, no matter how scattered my journal entries were or how abstract the writings or the drawings were, they were, and still are, an intentional vehicle to capture a moment in time and to have something to look back upon as an artistic reference.

I, as an artist, musician, and writer, use my journal entries for the continued creation of my art. However, there are endless examples of different professions outside of the arts that regularly use a physical journal as a tool in their work and research. Scientists, naturalists, and inventors are just some of the examples that come to mind.1 Unless you are lucky enough to have a photographic memory, it is nearly impossible to remember every idea or every piece of data without some form of analog or digital reminder.

Most importantly, though, as an adult human with attention issues and concerns, I’ve always looked for ways to maximize my concentration and refine my skills and I have constantly come back to some sort of imposed regular routine like journaling. Often this routine is nothing more than a half hour or less of time set aside daily or weekly to apply myself to a specific task or skill. At different times, I’ve used this to improve as an artist, as a musician, and as a writer. By being more purposeful and intentional, I have found ways to channel that energy to help push myself to be more focused in my development and evolution as an artist, writer, musician, and as an individual. If I am able to focus my energy in small chunks, I’m able to hold my own attention without much strife or anxiety and I’m able to see lasting results and the evolution of my work over extended periods of time. Some may just call this discipline, and it is a form of discipline, but, to me, it is simply a means to an end and a comprehensive way to combat my often scattered thoughts and short attention span.

Young learners and students are no different, just that most have not yet learned these or other important coping mechanisms. I also feel that the pandemic has unfortunately compounded many of these challenges for not only children and students but also for adult learners, teachers, and pretty much every human being on this planet. Adults may have tools and ‘tricks’ that help them maintain a higher sense of normalcy, but these are tools and processes that need to, especially with younger learners, be purposefully taught, modeled, and nurtured.

When discussing how one might learn the unique calls of different birds, Jon Young states that, “the only talent required for understanding the birds is awareness, and we all have that. What really counts is practice – motivated practice.”2 At its core, that is what journaling is. It is a way to regularly practice the skills of observation and documentation. Whether it be for an artistic or scientific purpose, journaling gives us an opportunity to document our journey and learning. We can even think of it as implementing a scientific approach to whatever we might be choosing to create.

Whether for journaling or for the exploration of new ways to express myself, one of the ‘tricks’ that I have used in the past is the use of cross curricular or cross disciplinary activities and methods. I use this not only to hold my own attention span, but also to increase knowledge retention through the connection of these multiple disciplines. By using the intersection of these varied disciplines with ourselves or young learners, we aim to create more meaningful pathways of learning and remembering. We are also giving students tools that can translate to other subjects, disciplines, and daily life, as well as important coping skills for future learning and success.

The thought of giving my students the opportunity to poetically and visually embrace and document the order and chaos of the natural world while still creating something new and unique gives me inspiration and meaning to my place in the natural cycles of learning and growing. By using these multiple disciplines, I believe that we will see a meaningful improvement in the cognitive skills of observation, focus, and knowledge retention. The closer we can look and observe, and the more intentional we are about that observation, the more we can connect to who we are as humans and individuals and how we fit into this mixture of natural and man-made world in which we exist.

Unit Overview

Educators are always looking for ways to maximize their students’ potential as well as teaching their content in a meaningful and interesting way. Through the use of nature journaling, I feel that we are able to accomplish maximized potential and deliver meaningful writing and arts content along with the many other benefits that come with any sustained and time on task learning. The best part is that none of these benefits will be mutually exclusive and will only stand to benefit from, and enhance, one another.

In this unit, we will be learning the process of journaling along with learning new and refined writing and drawing skills in the process. Students will be working over a six to eight-week period to create, reflect upon, and revise their journals as we go. We will be following a strict framework but one that allows a great deal of artistic freedom for the students (and myself) inside that framework. Students will be journaling during at least part of every class for those first six to eight weeks of school. If everything goes well, we will most likely end up journaling and discussing our observations for the entirety of those classes.

Most sessions will start out with a concentration or relaxation exercise followed by a drawing and writing prompt. Some elements that we plan on using will include still life drawing, poetry, and observational writing, along with mathematical elements such as measuring and statistics. We will be using a variety of visual art mediums along with a diverse array of creative and observational writing techniques. At the end of the unit, every student should have a nature journal with 12 to 16 entries, with every entry including some element of writing, detailed drawing, and numerical data.

My Philosophy of Art Instruction

As a practicing visual artist, musician, and writer, my personal philosophy is that everyone is an artist. Everyone starts out with the built-in ability, want, and maybe even, need, to create. With visual art, I use the Betty Edwards philosophy as an example. As creative beings, we believe that if one is able to learn how to write, one is able to learn how to draw.3 If you have the dexterity to write legibly, there is nothing holding you back from creating visually. Drawing, writing, playing music, and any form of creation is, to some level, a teachable skill.

With the arts, we make sure that students are exposed to them just as we would want students exposed to any other subject. In the same way that every student will not grow up to be a professional athlete, astrophysicist, or mathematician, not everyone will grow up to be a professional artist, writer, or musician or an educator of these art forms. However, being exposed to any or all of the aspects and disciplines of the arts provide a way for people of every age to grow and develop creative thinking skills which have proven to transfer to most other disciplines and professions. We, as a world, want and need creative thinkers. Every line of work, at its core, needs problem solvers. The arts help nurture creative thinking skills, which lead to creative problem solving children who grow into creative problem solving adults. Everyone benefits from exposure and immersion in the arts.

Demographics

I teach at Pittsburgh Dilworth PreK-5. Dilworth is an arts and humanities magnet within the Pittsburgh Public Schools. Because we are a full magnet school, we are privileged to have full time music and full time art faculty. I understand this privilege and hope that, someday, all of our district facilities and schools will have a more robust arts curriculum.

Our student demographics this past school year were about 60% African American, 30% White, and about 10% who identify as Mixed Race. Our individualized education program (IEP) students and gifted individualized education program (GIEP) students represent about 17% of our student population along with an economically disadvantaged population of a little over 50%.4

Background and Cross Curricular Approach

My school (within the Pittsburgh Public School System) is an urban school but with some key aspects of privilege and advantage. Although we are part of the larger Pittsburgh Public system, due to our magnet school status, we have a much higher access to visual art, writing, dance, theatre, and music, along with other amenities that many of the other schools in the district might not have as much access to.

Along with the access to the arts, we have, as part of our school campus, access to a well-maintained urban garden and are located within short walking distance of one of the largest public parks in the city. Our garden is home to numerous edible plants and also a variety of different flowers and other plants. There are intentional places that we will be able to use to sit and observe nature as the weather permits.

Even with our privileges and advantages as a school, we still have many of the same issues and challenges as other schools in the district. We still have difficulties with student concentration, academic focus, and other issues that can plague students of all ages. With the constant distance and use of screens, these issues, unfortunately, have seemed to become compounded during and since the pandemic. To be completely forthright, many of the behavioral issues that arise in my class tend to stem from these issues.

To combat these challenges and issues, I am proposing using the arts and their relation to our natural world (specifically the disciplines of writing and drawing) to promote student growth in the areas of focus, deeper levels of introspection, higher levels of concentration, and a more refined approach to observational skills. As an educator who has journaled in some form for most of my life, I have experienced the positive outcome of a routine-based approach to this activity.

By using regular nature journaling and imposing a flexible but consistent routine, this will give me the opportunity to put together an intentional and regular unit for my students to experience both writing and drawing, intertwined, in a cohesive practice using routine observation of the natural world around us.

I like to think that our nature time will be used as a refuge and escape from the often necessary but also distracting walls filled with data charts, number lines, and other classroom and building visuals. Even with the passing of cars and pedestrians, students can hopefully find solace in the act of escaping the confines of the concrete and brick building, even if it’s only for a few minutes a couple times a week.5

Content and Learning Objectives

A main objective of this unit is to increase ‘stick-with-it-ness’ and concentration skills in my students through the practice of nature journaling. As stated in my introduction, even when I was young, I could remember having trouble with concentration and with forcing myself to commit to something long enough to get better at it. Our students have many of the same challenges that seem to have only been compounded by the effects of being separated by a screen and distance and by the instantaneous stimuli, temptations, and distractions of ever-present cell-phones, laptops, and other digital media. If using short intervals of practice has been a useful tool for me to grasp or refine technical skills that would normally be too arduous for my attention span as an adult, imagine how much it could help younger learners!

Journaling in any form is an effective way to push engagement through consistent but short intervals of time. Scaffolding into longer stretches of concentration will hopefully encourage students to push themselves to improve their stamina when it comes to bigger projects. Along with improving stamina, the drawing, along with the writing, gives the students practice sketching and fleshing out their ideas along with practicing the concepts of planning. Even the poetic process can help to support transferable skills.

Technique Objectives for Improving Observational and Cognitive Skills

I like to teach still life drawing as a way to promote observational skills. Still life drawing forces, through concentrative repetition and routine, the observer (student) to look more closely at the object or objects being observed and learn to draw what they see and not just what they think they see. It can be a challenge to break the habits of using simplified symbols instead of actually drawing an object.6 Students are creatively forced to look for and use all of the elements of art to create their observational drawings. The elements of art include line, shape, form, color, value, texture, and space.

With the addition of a writing element, journaling now in a sense becomes an all-encompassing cross curricular superhero version of still life drawing. By asking the students to not only draw what they see, but to also write about their experience and what they see, we are discreetly nudging them to learn about the subject on multiple levels, from multiple angles, and including multiple disciplines, all while honing their concentration and observational skills. How can you describe the lines on the leaves? How can you explain how you used the visual art elements of value and texture to draw that cloud? Even though so much is green, how can you tell the difference between the leaves, the stems, and the grass? How could you explain and describe, in words, something you can see that others cannot?

Teaching Strategies

Whenever I have had the opportunity to have a student teacher in my classroom, I always have to ask myself to think of and remember all of the things that I do automatically and as second nature that a newer educator might not do out of habit yet. I come back to the example of a student teacher asking if I wanted them to discuss scissor safety and glue stick procedure again with a group of first graders when we had already gone over these concepts multiple times. As you might guess, my answer was yes and always yes. Reminders of procedures, routines, and safety habits can never be over-emphasized. Everything that is to be done well and eventually expected of students needs to be taught, modeled, and repeated. All those procedures were once new to everyone.7 We might forget it sometimes, but it was all new to even the most accomplished teachers at one point.

As with so many things in education, my first words of advice are not to get discouraged. I cannot emphasize this enough. We all, at some level, resist changes to our routines and ways of thinking and adding another task, routine, or procedure to any practice can feel like a cumbersome uphill battle. Coordinating and distributing the physical supplies of art-making alone can become a major task and now we are adding in the element of working outside, not only our normal environment, but physically and literally working outside of the building. I implore you not to get too stressed or entangled with the specifics of what you will be writing with or what you might be writing on. A journal doesn’t have to be a bound book and you don’t always have to use the same medium to create your work. I encourage experimentation. If you only have access to a stapler, some scrap paper, and a pencil or pen, you have the tools to journal. If you have access to watercolor painting supplies, that’s great, but if you have an abundance of ball point pens or an overflow of orange crayons, those can be just as effective. Projects and procedures do not need to be complex and cumbersome to be meaningful. The sheer act of a continued, methodical, and intentional process can give learners of any level or age an increase in stamina, skills, and (probably most importantly) an increase in confidence.

Please remember that this is a tool to be used and not a finished product. We should always make sure that we are de-emphasizing that these need to be ‘pretty pictures’ or finished pieces. We can think of the entire journal itself as a finished piece, or we can think of journaling as a tool we can use for research and self-reflection. During regular warmups, I will remind students that this is similar to a musician warming up with scales or an athlete warming up before going into play. What we do as a warmup is not to be viewed, in any way, as a polished product for display, but rather as a reference and practice material for the bigger project.

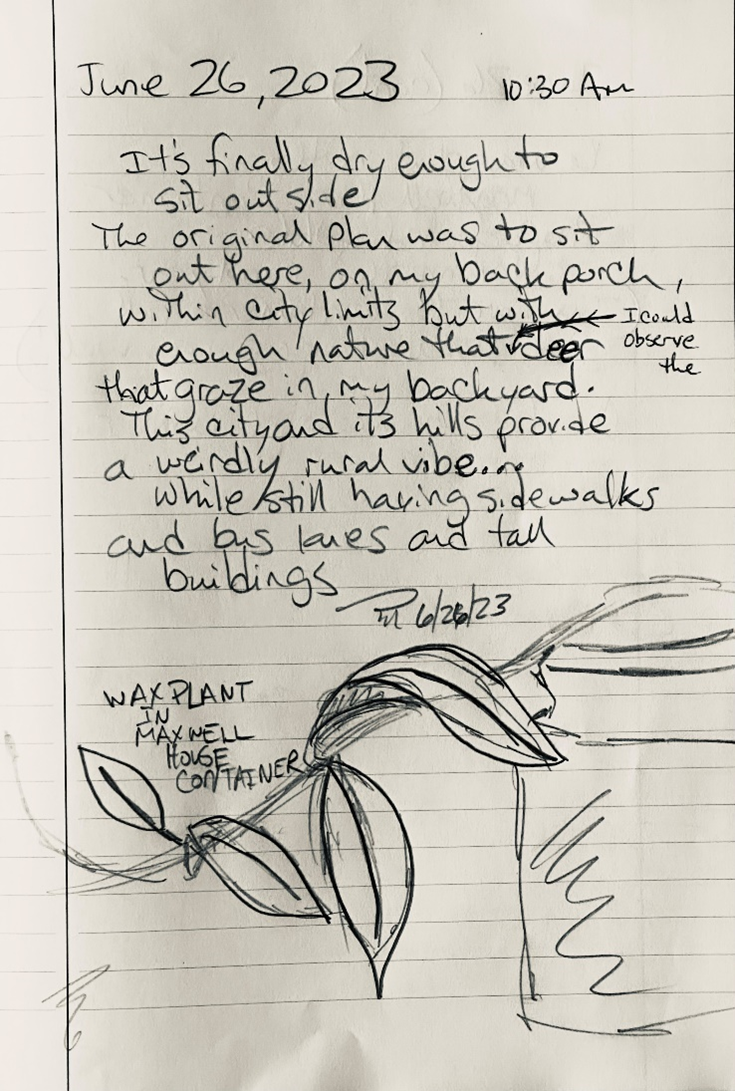

Above is an example of an entry from my journal. Please notice that it’s quite sketchy and not what most of us would describe as perfect, but it does include a detailed picture, creative writing, and data about the plant along with the date and time of the entry. This journal entry reminded me of a quotation from Elizabeth Gilbert’s book Big Magic. She states that “done is better than good.”8 Although I might not phrase it so harshly when applying it to younger students, as an arts instructor, I stand by this quotation and its core essence.

Elizabeth Gilbert also reminds us that, “the drive for perfectionism is a corrosive waste of time.”9 Too much work goes unmade, unfinished, unpublished, or even unthought-of in the pursuit of some unattainable goal of perfection. I go as far as telling my own students that, “perfection is a lie.” Anything worth doing is much better finished and in the world than it is withering away in a mind (or even worse, never even being thought about). Anytime we can get a student to create and find pride and self-confidence in what they created, it’s a good day. Journal entries are always something that we can come back to for revision or reflection so it is important that every entry have the key elements which we discussed every time we journal.

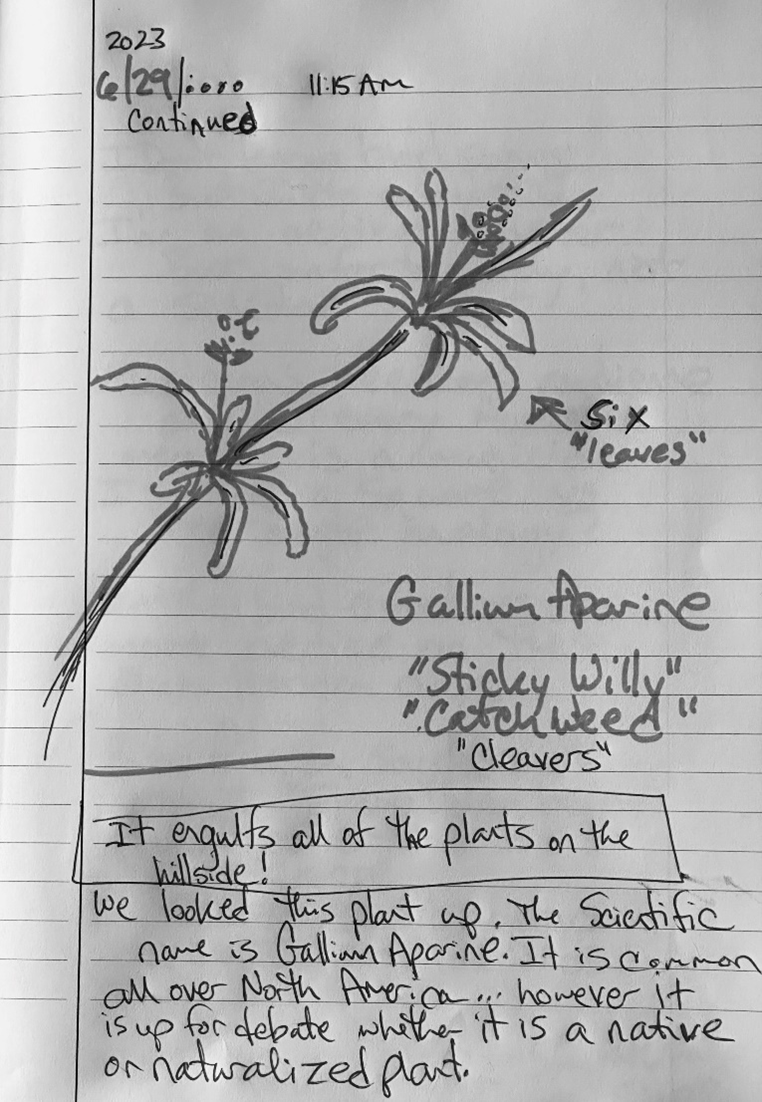

The journal entry below is my example of me using revisionary techniques in one of my journal entries. My initial observations were in my chosen sit spot without any technology. However, I went back, after my initial tech-free observations, and did research on the plant in question so that I would have more reference and a deeper understanding of this plant that was engulfing all the other plants on the hillside in my backyard.

Along with repetition and consistency I will be emphasizing the concept of time on task. Studies have shown that regular intentionally methodical time on task not only improves motor skills but can also improve concentration skills along with boosting student confidence. The physical action of writing or drawing can cement things into memory that tapping on a keyboard cannot.10

Unfortunately, I hear the phrase “I can’t” on a daily basis. Sometimes I follow with a “you mean you can’t yet?” But what if I had a way to help these students gain the confidence to start out with saying “I can”? Even if a student still feels apprehensive or hasn’t achieved the desired level yet, being able to start a task will hopefully give them the urge to see it through to completion. All too often, when projects are ‘one off’ types of endeavors, students tend to get caught up in this pursuit of perfection, worrying about the product over the process. With routine sessions of writing and drawing, students tend to be conditioned to understand that perfection isn’t as much the goal as improvement and completion. We want the students to appreciate the process and the journey as much as the shiny object on the pedestal.

This is where and why I will be including Jon Young’s idea of a sit spot. Young uses the idea of a sit spot as a way to become more aware of the calls and voices of birds. But this concept is easily applicable to anything that might require a higher amount of concentration or higher amount of time on task. In his book, Young discusses that “the only talent required for understanding the birds is awareness,”11 and it is awareness and intentional and motivated practice that can help any person at any level in any subject obtain a better understanding. For my application, I will not be using the sit spot specifically for recognizing bird sounds (although they could definitely be part of what we ‘hear’ when we’re outside) but instead using it loosely as an anchor for inspiration to build observational skills and stamina for concentration.

For more specifics on Jon Young’s sit spot concept, please check out the chapter discussing them in his book What the Robin Knows.12 John Muir Laws and Emilie Lygren’s book How to Teach Nature Journaling is also a great reference and expounds upon the sit spot for specific use in nature journaling.13

Classroom and Sit-Spot Activities

This unit is planned for the fall of 2023. It could technically be any time of the year but the fall in Pittsburgh seems to be a great combination of hospitable weather along with noticeable and spectacularly colorful changes in our natural environment.

The planned time frame is 10 to 14 classes over a six to eight-week span. The unit should take up the better part of our first nine week grading period.

Phase One: Student Introduction to Journaling

After my yearly review of routines, which usually takes one or two class periods, I would like to introduce my fourth and fifth grade classes to the concept of nature journaling. I will have examples of my own journals and I will also be regularly referencing concepts and techniques from How to Teach Nature Journaling by John Laws and Emilie Lygren. If everything goes as planned, we should be outside and in the garden on the third or fourth time that every group comes to art class.

It is important (and I say this to myself as much as anyone else) to ask the students what they feel should be included in the journal. Although I will guide them into the general vicinity of the outcomes I desire, it’s very useful to get and respond to their thoughts and ideas. I mean, kids have good ideas and will always feel more involved and connected if they’re part of the planning process.14 With many of my projects, we have, on countless occasions, ended up leaning more towards an aesthetic that more closely aligns with the curiosities of the students than my original aesthetic. As long as the students are engaged and my general concept and learning goals stay intact, does it really matter whether or not we are rigidly married to the original specifications? The plan is to keep on driving but let the students help choose which paths we take to get to our goal. I give the frame and parameters but it is always more meaningful when the learner decides what exactly to put into that frame.

The only required part at this level is that the students ascribe to a somewhat standardized form of documentation. Consistent documentation and labeling supports making it easy to reference ideas and thoughts. The routine would consist of always dating journal entries, adding any pertinent numerical details such as size or proportion, drawing their observation, and following the daily writing prompt.15 Documenting the date of a drawing has always been part of my regular classroom routine but I appreciate the addition of using actual measurable data to the process.16 Honestly, the addition of measurement will help support my later lessons on perspective and depth. Once again, cross-curricular learning is the secret underlying glue.

Depending on the class choices and how our introductory discussions go, prompts and activities might include:

- writing about an object without naming it

- How can you describe an object, plant, or animal without using the specific known word? A simple example might be: I saw this furry creature with longer ears hopping around in the corner of the garden. It was cute but I might not want to get too close.

- executing a detailed drawing of an object that they can see from their spot.

- These would preferably be objects that the students can observe up close, like a leaf or a twig, etc…

- It should always be something that the student can observe at that moment. We are drawing what we see, not what we think we see and not what we remember.

- writing a poem about the object

- How can you describe the object in deeper way?

- How could you personify the object or animal?

- If that leaf could communicate, what would it be thinking? How does that rabbit or mouse feel about us humans being in their space?

- measuring the object and/or comparing it to other objects. Using scale, proportion, and quantity to describe the object or animal.17

- How tall are the trees?

- How big is that flower?

- How does the size of the tree compare to the size of the flower?

- How many trees are there in relation to how many flowers?

- How can we describe the object or animal with numerical data?

- discussing, on paper, how we feel as individuals in this environment

- What is your mood?

- Does your mood change when you are outside?

- Does nature calm you? Does it make you anxious? Or maybe, do you feel indifferent? If so, can you please explain why?

- How does what we observe change? How does it stay the same?

- Are leaves the same color as last time we observed them?

- Did the sunflowers grow more?

- Are the sunflowers dying?

- What processes do you observe?

- Some writing prompts might include:

- What if this was the last time or the first time you saw this? Rachel Carson asks a similar question. How does that make you feel? How would you explain what you’re seeing?

- What if you didn’t have the actual word to describe the object or concept but instead had to explain it only using its attributions like color, shape, line, texture, etc…?

As stated previously, every journal entry should include some element of drawing, writing, and numerical data.

Phase Two: The Journal

Every student will get their own sketch book or journal (depending on what I am able to acquire through the district). The first day will consist of labeling and personalizing this journal. We will also be discussing the three components that we will be including in our nature journaling (drawing, writing, and numerical data). Since this is a cross-curricular unit, I want to emphasize the equity of writing and drawing along with constant documentation and data. This is as much a humble reminder to myself as it will be for the students. As stated above, the aim is to have every journal entry include detailed drawing, descriptive writing, and measurable numerical data.

Each class will consist of a visit to the school’s garden. I anticipate this being a longer process at the beginning until the students get into the routine. It will possibly take up the entire class period at the beginning. However, I also realize that it could very well end up being a longer process once the students become engaged in the drawing and writing. This would be a good problem to have! Since I’ve never done a formal lesson or unit around using our outdoor spaces, this will be a learning process for me as well as my students.

Every visit to the garden will begin with some form of reflection to center the students before beginning the actual process. This is where I would like to employ a briefer version of Young’s ‘Sit Spot’ at the beginning of every garden experience. This would be three to five minutes of silent reflection with no drawing or writing until I give the prompt. The silence will give everyone involved a chance to listen and observe and/or just have a moment of quiet reflection. When I have used silent reflection in the past, I have a strict rule of no talking or moving unless it is an emergency situation. I find that giving these strict boundaries, especially at the beginning, helps the students work on and improve their self-reflection and concentration skills. I will also be modeling the same desired behavior as I circulate through the group.

Upon completion of our moment of reflection, we would start into the chosen daily prompt and exercises. These will most definitely vary slightly depending on the choices of each individual class during our introductory and planning discussions.

Phase Three: Reflection

If a student has a well-documented account to look back upon, it’s easier to visually show growth with their writing and visual artwork. We can use this in much the same way an artist would look back through their portfolio to show growth or a musician can listen back through recordings of their past performances, and also how an author or poet would look back on their notes and writing sketches.

Both the process and the product of journal creation complements my continued emphasis on planning and revision that starts with my youngest students. Art takes time. Writing takes time. Habits take time. Refinement takes time. Reflection takes time. The goal is for every student to have a sequential set of entries to look back upon.

If time allows, I would like for the students to have the opportunity to present their journals and the journey they took creating them. At our school, these presentations usually take place during our morning meeting for the entire school to observe and enjoy. The goal would be for students to discuss the process, what they learned, what they liked or did not like, and how they might be able to use these skills in other classes and other areas of life. I do not plan on having every student present their journey but I would like to have at least a couple representatives from each fourth and fifth grade class be able to talk and share their work with all of our students.

Appendix on Implementing Pennsylvania Arts Standards

Standard 9.2.5.C – Relate art to various styles

We will be discussing still life art along with observational and technical drawing. Examples of scientific drawing will be used in correlation with certain drawing prompts. Writing examples of varying styles will also be used to illustrate the different concepts that we will touch upon with the writing prompts.

Standard 9.2.5.F – Application of appropriate vocabulary

All elements of visual art (line, shape, form, color, value, texture, and space) will be discussed along with the vocabulary that goes along with them. Concepts that we will be specifically touching upon other than the elements will include still life, shading, realism, depth, etc…

Standard 9.3.5.B – Describe work by comparison of similar and contrasting characteristics

Students will be able to chat about their work, what elements they used in the creation of their work. They will be able to compare their work with other students’ and also compare their work (writing and drawing) with previous entries.

Standard 9.3.5.D – Compare similarities and contrasts using vocabulary of ‘critical response’

We will have regular discussion on how the work was created, what art elements were used, and how those elements were used. We will also be able to chat about the similarities and differences of the students’ responses to the various writing and drawing prompts.

Notes

1 John Muir Laws and Emilie Lygren. How to Teach Nature Journaling, 3

2 Jon Young. What the Robin Knows, 48

3 Betty Edwards. Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, 3

4 “Pittsburgh Dilworth,” Pittsburgh Public Schools

5 John Muir Laws and Emilie Lygren. How to Teach Nature Journaling, 3

6 Betty Edwards. Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, 88

7 Ron Ritchhart. Creating Cultures of Thinking, 9

8 Elizabeth Gilbert, Big Magic, 191

9 Elizabeth Gilbert, Big Magic, 184

10 John Muir Laws and Emilie Lygren. How to Teach Nature Journaling, 2

11 Jon Young. What the Robin Knows, 48

12 Jon Young. What the Robin Knows, 48

13 John Muir Laws and Emilie Lygren. How to Teach Nature Journaling, 154-157

14 Ron Ritchhart. Creating Cultures of Thinking, 8

15 John Muir Laws and Emilie Lygren. How to Teach Nature Journaling, 18

16 John Muir Laws and Emilie Lygren. How to Teach Nature Journaling, 6

17 John Muir Laws and Emilie Lygren. How to Teach Nature Journaling, 18-19

Bibliography

Chodron, Pema. 2016. When Things Fall Apart: Heart Advice for Difficult Times. Boulder, Colorado: Shambhala Publications.

Edwards, Betty. 1989. Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain: A Course in Enhancing Creativity and Artistic Confidence. Los Angeles: J.P. Tarcher.

Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art, Courtenay Palmer, and Kiffin Steurer. 2007. Artist to Artist: 23 Major Illustrators Talk to Children About Their Art. Edited by Patricia Lee Gauch and David Briggs. Translated by Samuel C. Morse. New York, NY: Philomel Books.

Franklin, Devin. 2019. Put on Your Owl Eyes: Open Your Senses & Discover Nature’s Secrets, Mapping, Tracking & Journaling Activities. 1st ed. Story Publishing, LLC.

Gilbert, Elizabeth. 2015. Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Thorndike Press.

La Mancusa, Katherine C. 1965. Source Book for Art Teachers. Scranton, PA: International Textbook Company.

Laws, John M., and Emilie Lygren. 2020. How to Teach Nature Journaling: Curiosity, Wonder, Attention. Berkeley, CA: Heyday.

Muhammad, Gholdy, and Bettina L. Love. 2020. Cultivating Genius: An Equity Framework for Culturally and Historically Responsive Literacy. New York, NY: Scholastic.

Ritchhart, Ron. 2015. Creating Cultures of Thinking. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Young, Jon. 2012. What the Robin Knows: How Birds Reveal the Secrets of the Natural World. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Comments (0)

THANK YOU — your feedback is very important to us! Give Feedback