Introduction

"If we want to understand a work of art, we should look at the time in which it was created, the circumstances that determined in style and art expression as well as the individual forces that led the artist to his form of expression." 1

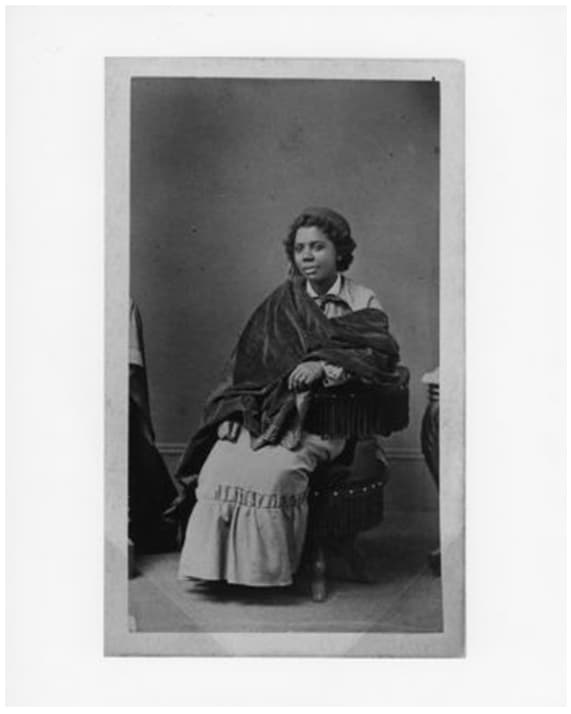

"Against all odds, Mary Edmonia Lewis aspired to be a sculptor. Who can really say when her dreams began? That she had them at all is rather miraculous." 2

These two quotes, by Vicktor Lowenfeld and Kirsten P. Buick respectively, sum up my unit. I want my students to understand that art is a reflection of the time and place in which it was created and that artists own personal identity influence the artwork. I will accomplish this by focusing on Edmonia Lewis, a sculptor of great accomplishment, who had a miraculous dream to be an artist, as Buick said. What I find truly inspirational is that she achieved her dream.

Edmonia Lewis was biracial; her father was African American and her mother was of Native American descent. Born circa 1844, she was a free woman of color during the Civil War. Raised by her mother's Chippewa tribe after being orphaned at the age of 4, she was able to become America's first African American sculptor of note. Her work, while reflective of the fashionable Neoclassical style, is also reflective of her heritage. She was attracted to subjects that reflected her identity, both Native American subjects and African American. Yet she worked within the Neoclassical style, which was based on the imitation of Greek and Roman sculpture. While she gained recognition during her life, she ultimately was forgotten and only recently has begun to gain her rightful place as an important American artist. She will be a good role model for students because she overcame several substantial societal limitations. She pursued her dream of being an artist despite being Native American and African American, at a time in history that made being either was extremely challenging. The country was being torn apart by the Civil War, and, yet another challenge, she was a "she", a female, at a time when it was extremely hard for women to become artists and doubly so to become sculptors, since this was the most physically demanding of the fine arts. In this unit, I will be able to explore how an artist's identity shapes their work and how their cultural and historical context also shapes an artist's work.

I have always been interested in the story of Edmonia Lewis. I have long felt she would be a wonderful subject for a unit for my middle school art students but have never had the time or opportunity to develop this idea. This seminar, "Understanding History and Society through Images", has presented me with the perfect opportunity. Edmonia Lewis' story is truly a reflection of the time in which she lived. This unit also will give me the chance to connect to several aspects of art history and the culture contemporary to her life. I felt such a unit would also give me the opportunity to explore art history in depth. Since she was a neoclassical sculptor, I decided this should be an Art I unit. My 8 th grade class takes art for high school credit, Art I. In 8 th grade, the students study civics in their social studies class. Looking at Neoclassical art and how that movement was reflective of the democratic ideals of America will connect well to their civics class. Their textbook is filled with Neoclassical art and architecture. Providing a background into this art style should support their civics curriculum. This Course Unit also gives me the opportunity to think about strategies appropriate to teaching art history. I feel I can explore art history teaching strategies with my Art I students.

Comments: