Background

Pathogens I - Bacteria

Microbes can be one of four types: bacteria, viruses, protozoa, and fungi. Two of the four will be discussed as they relate to disease, drug treatment, and drug resistance. The hierarchal domain Bacteria (prokaryotes) includes Proteobacteria, Chlamydia, Spirochetes, Gram-positive, and Cyanobacteria. All bacteria are singled celled organisms with no nucleus and are 1/100 th the size of an average human cell. 4

Microbes like bacteria that naturally exist in humans are collectively known as normal flora or indigenous microbiota. In general, bacteria that reside as part of the normal flora are mutualistic, meaning that both organisms benefit from contact with one another; however some bacteria have the potential to become parasitic and even pathogenic. Although a Mayo Clinic article on microbes states that only 1% of bacteria actually cause disease. 5 Through contact with our environment, bacterial populations find residence on almost every surface of our body.

In researching microbes that exist on the surface of the skin, Grice, from the National Institutes of Health, found the varying preferences of skin-dwelling bacteria. According to her research, some bacteria seek warm, moist places like armpits and toes. Some bacteria prefer dry areas like backs. 6 As we encounter each other, bacterial strains are passing from one person to the next, adding to the diversity of bacteria thriving on the surface of any individual's skin. Interestingly, the Belly Button Biodiversity project found 4,000 different bacterial strains just inside human belly buttons, showing the wide variety of bacterial fauna in small space. 7

The two most common microbes that exist as part of the normal flora belong to genus Staphylococcus. Of this group are the species S. epidermidis and S. aureus. 8 Staphylococcus bacteria are named accordingly to their clustered grape-like appearance. "Cocci" in Greek means round. Both species of Staphylococcus are found throughout the skin, in the conjunctiva of the eyes, and on the mucous membranes of the nose, pharynx, mouth, lower gastrointestinal tract, urethra, and vagina. Other abundant bacteria include Streptococcus pneumoniae found in the upper respiratory tract and the problematic Bacteriodes, which are found in the greatest number in the lower intestinal tract and which may cause colon cancer.

Students may wonder why some bacteria affect humans in specific tissues others do not. The reason for this is because of tissue specificity. Bacterial colonies prefer certain tissues because of the nutrients found on the tissue while others adhere and have special receptors that are complementary to ligands found on the tissue (i.e. some bacterial cells have affinity for certain tissues). Though it may be difficult to change people's minds on the merits of tiny microbes living and thriving on the surface of body, perhaps an awareness of their normal flora's helpfulness will change people's minds. First, bacteria help us to synthesize vitamins (K & B12) and antibiotic medications. Second, some bacterial colonies prevent the invasion of harmful pathogens. Third, intestinal bacterial colonies maintain the balance of our normal flora and prevent gastrointestinal problems and aid in digestion. Beyond the flora found on our bodies, bacteria are used in food preparation, agriculture, decomposition of plant and animal waste, and drug delivery. 9

Because of the diversity of bacterial life and their ability to reproduce quickly, many bacterial types do cause infectious diseases. Staphylococcus infections and tuberculosis will be discussed as examples of diseases caused by pathogenic bacteria.

Bacterial Life Cycle

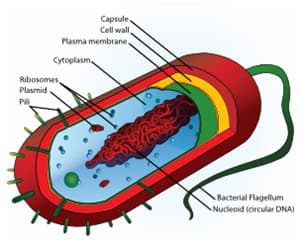

Bacteria are prokaryotic, singled-celled, asexually-reproducing organisms. A bacterium has the basic structure of a capsule, cell wall, plasma membrane, cytoplasm with ribosome, plasmid, pilli, plasmids, and nucleiod region (Figure 1). Bacterial motility is dependent upon a whip-like flagella. Unlike eukaryotic cells, the cell wall of a bacterial cell mechanically strong, like a plant cell wall, giving the bacterium its rigidity. All the nutrients, enzymes, water, and electrolytes a bacterium needs in order to survive and reproduce can be found in the contents of its cytoplasm. Ribosomes, like those found in eukaryotes, function in the synthesis of proteins and are an important structure in the formation of new bacteria. Plasmids are short sections of self-replicating DNA molecules that are not part of the remaining bacterial DNA. The nucleiod region, contains bacterial DNA, and serves a template for replication. 10

Fig. 1. Bacterium Structure showing outer layers and inner nucleoid region. Figure obtained from free public domain site Clker.com 11

Because bacterial do not require a host, or second bacterium to reproduce, reproduction is done through asexual binary fission. In binary fission, which for some species under the right conditions can occur every 30 minutes, bacterial DNA is first replicated in a loop. Two sets of circular DNA are made for the daughter cells. Once the loops of DNA are completed, they move towards opposite ends of the bacterial cell to prepare for cytokinesis. Cytokinesis finishes binary fission with the pinching-off and separation of the two newly formed daughter cells. The resultant daughter cells of binary fission are genetically identical to its parent; however, mutations due to the rapid reproduction rate and short generation spans can cause mutations. 12

Genetic diversity among bacterial populations are achieved not only through mutations, but through genetic recombination. One way to achieve genetic recombination is through transformation. This occurs when a healthy bacterial cell takes up DNA from dead or pathogenic bacteria. The nonpathogenic bacteria break the circular DNA of the compromised bacteria and replace the broken fragments with its own DNA, thus achieving recombination. A second method to achieve recombination is conjugation. Conjugation requires two bacterial cells and their plasmids. As mentioned before, plasmids are short circular strands of self-replication DNA. During conjugation one bacterium is a donor and a second is the recipient. The donor bacterium transmits a copy of its plasmid across a sex pilus (a physical structure connecting the two bacteria) and replicates in the recipient bacterium, thus completing conjugation. A third recombinant method is transduction. Transduction involves a bacteriophage (viruses with bacterial DNA). Initially in transduction, bacteriophage injects their phage DNA into a bacterial cell where new phage proteins are made. When new bacteriophage are assembled from proteins, newly assembled bacteriophage containing recombinant DNA, lyse and infect a second bacterium. With the injection of new phage DNA into a second bacterium, transduction is complete. 13

Types of Bacteria

Staphylococcus aureus

Staphylococcus aureus is a spherical bacterium commonly found in the normal plethora of humans. Clusters of S. aureus appear grape-like and accumulate in areas like the nose, skin, gastrointestinal tract, and mouth. Though some species of the genus Staphylococcus are nonpathogenic, S. aureus does have the potential to cause disease. A staph infection is an infection from the various strains of Staphylococcus bacteria. Typical S. aureus infections include pimples, boils, abscesses, pneumonia, endocarditis, and toxic shock syndrome. S. aureus is particularly important to health care workers who need to take great care to prevent nosocomial infections (hospital-acquired). S. aureus is an effective bacterial pathogen because its surface proteins promote the invasion of its host tissues. It suppresses phagocytosis and disguises itself from immune cells that would seek to destroy it. Also, S. aureus produces toxins on its cell surface that promote the lysis of eukaryotic cell membranes. Finally, S. aureus has developed both inherent and acquired resistance to antimicrobial agents.

S. aureus destroys tissues by first adhering to the surface proteins on their host cell. Their adhesion to the host cell is followed by invasion into the cell. This invasion occurs by a complex process involving membrane-damaging toxins, which can cause the perforation of the host cell membrane. Once inside, the bacterial DNA replicates like other bacteria. 14

Tuberculosis

One of the earliest known infectious diseases is tuberculosis, which is caused by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a bacterium belonging to the phylum Actinobacteria and the order Actinomycetales. Skeletal remains of prehistoric humans has shown evidence of M. tuberculosis, Hippocrates knew its deadly potential in ancient Greece, and before 1900 tuberculosis killed 1 in 7 persons in Europe. 15 During the last 200 years the cause for tuberculosis was wildly speculated, studied, and finally identified in 1882 by Robert Koch.

In Aldridge's How Drugs Work she mentions that though the number of tuberculosis cases has decreased since 1900 to 1980, the bacterial disease has experienced a recent resurgence. According to WHO (World Health Organization), there has been a steady rise of cases worldwide. 16 A 2011 article from "The Lancet" stated that there are approximately 9 million tuberculosis cases worldwide, primarily affecting sub-Saharan, Eastern Europe, and Asia. India by far has the highest number of cases with 26% of the world total of TB cases. 17

So what exactly is tuberculosis? Tuberculosis is an airborne infectious disease caused by bacterial growth and accumulation in the lungs. The disease can spread simply through the sneezing, coughing, and speaking of an infected TB patient. Though many people may have been exposed to TB, the bacteria may lay dormant inside an infected person. Those with latent TB can live normally and may not show signs or symptoms of the disease. It is only when the bacterial cells become active that people become sick. If a person has full blown TB, then they are infectious and their immune system is incapable of suppressing the bacterial growth. Signs of TB disease include persistent cough, fatigue, weight loss, fever, and coughing up blood.

Pathogens II - Viruses

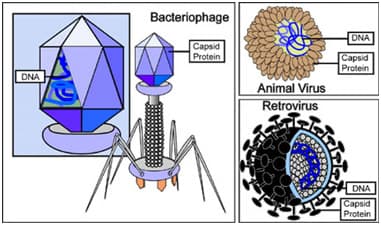

Unlike bacteria, viruses, are not prokaryotes since they do not have the internal machinery bacteria possess beyond genetic material, thus viruses depend on its hosts to reproduce. There are four different viral structures: helical, polyhedral, enveloped, bacteriophage (Figure 2). The difference between these structures lies in their protein capsule, known as a capsid. The smallest virus is only 20 nm in diameter. Inside the capsid, the genetic material can either be single-stranded or double stranded DNA or RNA. Though different in size, shape, and genetic content, all viruses are dependent upon their host cell's resources and mechanisms to reproduce. Viruses have a range of hosts that they can infect depending on surface proteins on the virus and receptors on its host cell. In most cases, when the host cell dies and the virus cannot find surrounding cells to infect, the virus does not spread.

Figure 2. Virus types showing the differences in structure between bacteriophage, animal virus, and retrovirus. Figure obtained from free public domain site - Science Kids. 18

Viral Life Cycle

A virus is an obligate parasite, meaning that it is dependent on its host for reproduction. Some viruses have a broad range of hosts and some may have a narrow range thus making virus specific for its host. Eukaryotic organisms are affected by more tissue-specific viruses, infecting specific cells within organs like the liver or lungs. 19 The process of infecting a host starts when a virus's capsid proteins are recognized by a host's receptors. If there is a receptor-protein match on the cell membrane endocytosis or injection of the viral genome occurs.

The reproductive cycle of a virus begins when the genome of a virus enters its host. DNA viruses and RNA viruses replicate differently from each other but both require the host cell's replication machinery (i.e. DNA polymerase, RNA polymerase, reverse transcriptase). For example, a virus with phage DNA as the genetic material, phage DNA is replicated using the host cell's DNA polymerase, making hundreds of new copies. On the other hand, if the virus contains RNA, then viral RNA would be transcribed into mRNA and then translated into chains of new viral proteins during protein synthesis. The end result of the process is the same — reproduction of new viruses to be released out of the host cell to infect neighboring cells. Viral microbes, influenza, tuberculosis, and HIV are explored as examples of second type or pathogenic microbe.

Type of Viruses

Influenza

The story of the flu virus parallels human history. Early accounts can be found in ancient Egypt in pictographs depicting Egyptian royalties with polio, clubfoot, and smallpox. 20 Viral diseases were known in Greece in 412 B.C as told by Hippocrates. The British in 1485 called it the "sweating sickness" and probably the most well documented of the epidemic was the 1918 outbreak where 50 million people died of Spanish flu. 21 Today, the different variations and permeations of the flu are consistently in the news: avian flu, H1N1, swine flu. With so many variations, the difficulty of keeping the virus in check is easy to understand.

So why has the influenza virus been so successful? One reason is its ability to adapt to its host (antigenic shift), and to take over its hosts' replication machinery. This reason alone, according to Aldridge in Magic Molecules, makes the virus difficult for the immune system to handle. 22 Second, because most humans have some form of the virus from previous exposure, there's almost an endless supply of existing genes to create new re-assorted genes. Finally, influenza virus has been successful because of its mode of transmission. The virus can be spread through the air in a simple sneeze or cough. Symptoms of an influenza virus infection include fever, sore throat, aches, and pains. These symptoms usually create an opportunity for other infectious diseases like pneumonia to infect a person: even if the influenza infection is not fatal, it might weaken a person sufficiently that they die from other infections.

Influenza virus is an RNA virus about 130 nm in size and spherical or filamentous in shape. Its human variants, A and B, differ from each other by the number of proteins on its surface. The proteins on its surface are hemagglutinin and neuraminidase. Hemagglutinin's various mutations can cause antibodies, already produced in a person from a prior years experience with influenza, to not be able to recognize its new form. This antigenic shift is the reason for seasonal flu. Neuraminidase is also a protein but in the form of an enzyme that allows the virus to penetrate through mucosal layer protecting the respiratory tract. Neuraminidase functions to penetrate the cell membrane of its host cells in order to allow entry of the viral RNA. The virus replicates by first attaching to the host cell surface using its proteins. It then enters the host cell by receptor-mediated endocytosis. When the structure surrounding the virus is disintegrated the viral RNA is released and transmitted to the nucleus. In the nucleus polymerase reactions take place to eventually synthesize new viral proteins. When the cell reaches a high concentration of virions, it is released into the environment by an enzyme that lyses the cell membrane of its host. Health care professionals are simply incapable of predicting the virulence of the virus, its host target, where it will strike, and who it will strike because of the multiple permeations and reproductive rate of viruses. Health care professional's main action is to inform the public, and manage the outbreaks as best as possible.

Retroviruses and HIV

Retroviruses like HIV have an additional complication in its reproduction within the host cell. The genome of retroviruses is encoded in RNA. Retroviruses, upon entering the host cell, can create DNA from the genomic RNA template, because of the presence of a viral protein, reverse transcriptase. Reverse transcriptase allows for the production of a provirus (viral genes embedded into the hosts' genome) that can eventually become the template for viral proteins to create new HIV. Unlike unaffected cells, the genomic DNA of the host is modified to include a template containing portions of viral DNA that are ultimately transcribed into mRNA and finally into new viral proteins. These new viral proteins repackage themselves into mature viruses ready to infect other cells. 23

HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) is a type of retrovirus responsible for AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). The virus, and subsequently the disease, gained increasing incidence in the early 1980s among young homosexual men, blood transfusion patients, infected mothers passing the disease to their babies, and those having sexual intercourse with infected persons. According to the group AVERT, an organization dedicated to averting the spread of HIV and AIDS, as of 2010, 34 million people are living with HIV/AIDS. In fact, the number of newly infected persons continues to rise by an estimated 2.2 to 2.7 million every single year. 24

Comments: