Student Activities

Writer's workshop, a 60 minute block of time, will begin with a 15-20 minute daily mini-lesson which will highlight each of the following topics. These mini lessons build on each other, but many of them can be used a self-contained lesson, or repeated more than one time, if you see your students struggling in a specific area. Some of these mini-lessons will use published writing to help demonstrate the concept; however, more often, I will select authentic pieces from one of my students to help demonstrate how we might enhance his/her writing by modeling the concept covered that day.

Mini Lessons

What is a memoir?

To kick start this unit, students will gain a clear understanding of what exactly memoir writing is. I will be using Dreams from my Father, by Barack Obama, periodically to demonstrate various aspects of the genre. I chose this book because I wanted to pick a person students know and admire, and also because the book was very descriptive. I will pose the question: What do you think memoir writing is? Students will brainstorm their ideas. Then, I will read two passages to them: one from Obama's book and then one from Goldilocks and the Three Bears.

- It was well past midnight by the time I crawled through a fence that led to an alleyway. I found a dry spot, propped my luggage beneath me, and fell asleep, the sound of drums softly shaping my dreams. In the morning, I woke up to find a white hen pecking at the garbage near my feet. Across the street, a homeless man was washing himself at an open hydrant and didn't object when I joined him. There was still no one home at the apartment, but Sadie answered his phone when I called him and told me to catch a cab to his place on the Upper East Side. 9

- There once was a little girl named Goldilocks. One day she took a walk in the forest. Goldilocks saw a house and went in. She found three bowls of porridge. One was cold. One was hot. One was just right. 10

Students will have to identify which is an example of memoir writing and why. I will then state that memoir writing is a memory of an event in your life, what you learned from it or how it changed you. It should be written in first person. Students will then be encouraged to write about a recent event in their life and attempt to discover the meaning of these moments.

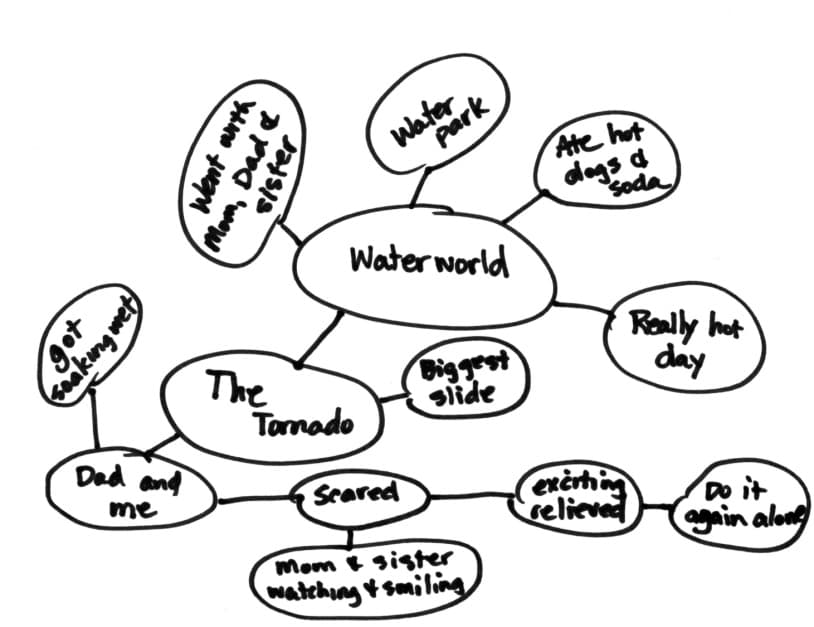

Brainstorming special moments and digging deeper

Students will be encouraged to write down events and why each event was meaningful to them. For example, if a child writes "I went to the water park with my family," they would then need to identify what about that experience was important to them: how did they feel before they went and after, why was the event special, what emotions did they experience, and how did the experience change them. Students will record their special moment in a story web (example below) remembering these reflective notations showing purpose, emotions felt and what people, places, or things are connected with this memory.

Turning an event into a memoir

Taking another look at Dreams from my Father, I will read two pieces of prose: 1) an actual excerpt:

"Barry? Barry, is this you?"

"Yes…Who's this?"

"Yes, Barry…this is your Aunt Jane.

In Nairobi. Can you hear me?"

"I'm sorry –who did you say you were?"

He is killed in a car accident. Hello? Can you hear me? I say,

your father is dead. Barry, please call your uncle in Boston and tell him.

I can't talk now, okay, Barry. I will

try to call you again…"

That was all. The line cut off, and I sat down on the couch,

smelling eggs burn in the kitchen, staring at

cracks in the plaster, trying to measure my loss. 11

Then I will read one that I wrote:

My Aunt Jane from Nairobi called me. She sounded upset. She told me that my father died in a car accident and I should call my uncle in Boston. Then she hung up and I sat down on the couch.

Students will then discuss which passage was more descriptive and why. How were they different? Which piece of writing showed that Barack Obama's life had been transformed? How did each piece make you feel?

Show not tell

The concept of "show-not-tell" is by far one of the most challenging to teach young students, a lesson that could be taught over and over again. Most likely, students will want to write about something they did over the summer, a birthday party or a special holiday. The events will be listed chronologically, telling the reader what happened step by step. I will read this example of typical student writing that tells:

Last weekend I went to Waterworld. I went with my mom, my dad, and my big sister. We went on a really big slide. I was scared. We ate hot dogs. It was hot. Then, the park closed and we went home. I had a lot fun.

To combat the dilemma of telling, not showing I'll re-read the excerpt that we read in the previous lesson from Obama's book. This time, I will ask them to close their eyes while I read it to them and try to visualize what is happening. Afterward, they will quickly draw what they heard and write descriptive words to explain their thinking and feelings. Students will then share their writing with a table partner. Could they see the writing in their mind? Good writing creates images in our head. Then, after reviewing the story web I drew in an earlier mini-lesson, I will read a revised Waterworld story asking the students to close their eyes and again, try to visualize the action:

I stretched my neck up to look at the people climbing the stairs to the top of The Tornado. I'm not going up there, I thought, but my Dad said he'd go with me if I tried. Climbing into the inner tube, I sat behind my Dad. My arms were glued tightly around his waist as we flew down. Squeezing my eyes shut, in an attempt to keep the buckets of water from covering me, we seemed to speed up as we headed down the long, curvy canal. Finally reaching the bottom with a splash as big as a whale's tail smacking the water, I saw my mom and big sister by the railing, watching our descent, laughing and smiling at our adventure.

Again, I'll ask students to draw what they visualized during my reading and share their pictures with a table partner. Over time, before students' conference with me or their peers, these young authors will begin to check their writing to make sure that it passes this visual test: Can I see the action in my head when I read my writing?

Effective leads

Catchy or effective leads will determine if a reader will continue to read the story. However, writing effective leads is not natural for most young writers. For this particular mini-lesson I would take a piece of writing from one of my students and use it as a way to demonstrate different ways to catch the reader's attention. A sentence like "Last weekend I went to the park" can be transformed fairly easily:

- Start with a question: Guess what I did at the park last weekend?

- Start with a strong statement: I was so wobbly I thought I was going to faint when I got off the tire swing!

- Start with a quotation: "Mom! I hollered. "Watch me jump off the swing!"

- Start with vivid description: I went down the slide so fast that my hair stuck to my face.

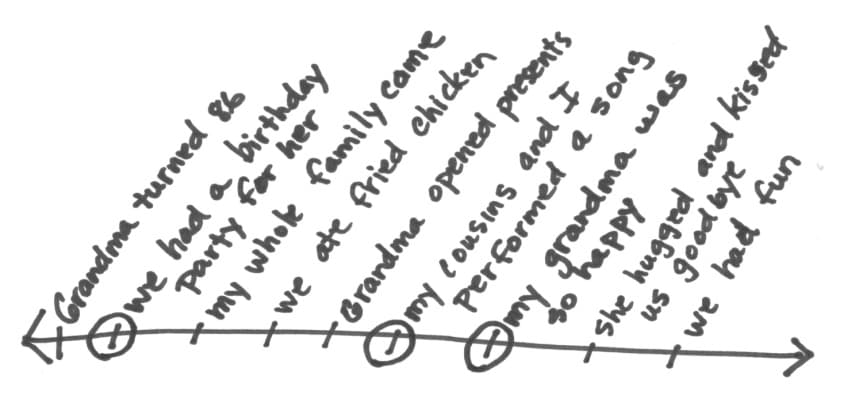

Sequencing and pacing

"Authors move through their stories using various devices such as dialogue, specific events, or transitional words and phrases like first, then, next, last, after lunch, weeks passed, the next day, tomorrow, and after a while." 12 Brainstorm a list of transitional words with students and keep them on an anchor chart in the classroom. Also, when students are writing it's important to think about what parts can you fast forward through and when you need to slow down. Let's say one of your students wrote about Grandma's birthday party. Not all events that happened should have equal weight. What are the small moments that make the story meaningful? Have students make a timeline of events that they want to write about. This will be their outline. Then, they should circle the two or three small moments where they want to slow down and add more descriptive elements.

Writing memorable endings

Just as important as effective beginnings, the writing needs to hold the reader's attention and keep them wondering. "The perfect ending should take your readers slightly by surprise and yet seem exactly right…It's like the curtain line in a theatrical comedy…What usually works best is a quotation. Go back through your notes to find some remark that has a sense of finality, or that's funny, or adds an unexpected closing detail." 13 To demonstrate this, I will take a piece of student writing about Grandma's birthday party with a less than memorable ending, "I had fun at Grandma's and then I went home." Different ideas suggested in Trait-Based Mini-Lessons 14 for memorable endings include:

- Re-state or summarize an important idea: Grandma was so happy that her whole family was there to celebrate her special day.

- End with something that was learned: I realized that Grandma's whole family being at her party was the best present of all.

- Use humor: When I went to hug Grandma good bye I tripped on a chair and fell face first into a piece of birthday cake. I guess I get two pieces today!

- Look into the future: I hope that I can always celebrate Grandma's birthday with her.

- Make a personal observation (something learned): My family may be a little kooky but it's fun that we're always there for each other on special days.

How to use dialogue in memoir

To demonstrate the use of dialogue in students' memoirs, I plan to introduce the genre of the graphic novel. This will be very exciting as many of them have already read graphic novels and might even think of them as a guilty pleasure, as opposed to legitimate reading. The graphic novel is a perfect way to show students to the idea of dialogue because it's typically formatted with speech/thought bubbles separate from narration. I will introduce the book, Barack Obama, The Comic Book Biography, and read sections of it to them showing them this format. Children will then pick an event and use an 8-frame graphic organizer (or white piece of paper folded into 4 sections—front and back) to organize their story into sections and including illustrations, narration and dialogue in each frame. My hope is that having to be very deliberate about dialogue in this format will transform students' use of dialogue in a more traditional format, as well. Also, I have found that once children know how to use dialogue in their writing, they tend to forget about weaving in the narrative component and their writing becomes straight dialogue. The graphic novel genre allows them to explore and organize both aspects of a piece in a graphic format.

Voice

What is voice? It's fairly abstract especially for young learners. Voice is an individual writer's style and uniqueness. If I were to read a Junie B. Jones passage (young children's chapter book series by Barbara Park), students would know exactly what author's writing we were listening to by Junie B. Jones's unique, young, quirky dialogue. Just as writing should have voice so do other forms of art. To demonstrate voice in visual art, I will show examples several different portraits of Barack Obama found on the internet. Though they are of the same subject, the voice of each is very different. Each evoke different feelings; some portraits seem powerful, some angry, and others are more sensitive. We will compare and contrast the similarities and differences.

Then we'll revisit the second mini-lesson, "Turning an event into a memoir?" and take another look at the two passages. After reading the two passages again, I will have students compare and contrast them. How are they alike? How are they different? Which one is more interesting? Which one showed change? Why? Hopefully the students will agree that the first passage demonstrates better voice.

Young authors will be challenged to their own stories listening for voice and commenting on voice in other classmates' writing during peer editing and seminar.

Using flashback to show purpose in an event

While reading The Art of Teaching Writing by Lucy Calkins I was inspired by the use of flashback to build a memorable moment and show how separate events are actually linked together. I will read another passage from Obama's memoir about the memory of his father at the time of his father's death:

At the time of his death, my father remained a myth to me, both more and less than a man. He had left Hawaii back in 1963 when I was only two years old, so that as a child I knew him only through the stories that my mother and grandparents told. They all had their favorites, each one seamless, burnished smooth from repeated use. I can still picture Gramps leaning back in his old stuffed chair after dinner, sipping whiskey and cleaning his teeth with the cellophane from his cigarette pack, recounting the time that my father almost threw a man off the Pali Lookout because of a pipe. 15

Students may have multiple stories that have a common thread; when combined through the use of flashback these events could show the transformation necessary for the piece of writing to be considered a memoir. I will find current student work where this technique can be used to model flashback; first working with a student one-on-one and then modeling the process whole class during a mini-lesson.

True confessions: reflecting on a mistake

Everyone makes mistakes. Students will take one of their memories where they did something they regret, but re-write it in the form of a letter to the person to whom they are apologizing. This format, modeled after an autobiography we read in our seminar, Confessions of St. Augustine, is a good set-up for younger students to reflect on an event in their life and how this event transformed them. I will read the following passage to them about when St. Augustine, 1700 years ago, confesses to God about stealing pears as a boy:

I already had plenty of what I stole, and of much better quality too, and I had no desire to enjoy it when I resolved to steal it. I simply wanted to enjoy the theft for its own sake, and the sin. Close to our vineyard there was a pear tree laden with fruit. This fruit was not enticing, either in appearance or in flavor. We nasty lads went there to shake down the fruit and carry it off at the dead of night…we derived pleasure from the deed simply because it was forbidden 16

Students will not be expected to write to God; however, this example does show students the use of descriptive language, showing-not-telling, and how St. Augustine's life changed because of his mistake. Students will be expected to transform one of their pieces about a mistake they made (and what they learned from their mistake) including rising action, dialogue and descriptive details but in the form of a letter.

Publishing a hard cover book

The culminating activity for my students will be to publish one of their stories in a hardbound book (purchase the blank books from www.barebooks.com for about $2 each). Students will have to organize their story into 14 pages including illustrations on each. Once they have done this, they will then copy the story and illustrations into their own hard cover book.

Comments: