Strategies and Content Objectives

Big Ideas of Lesson 1: Numbers, units, unit and general fractions, division

Almost all numbers have units. This lesson will start with exposing students to the various numbers and units that will be used during the year in chemistry (e.g., 12 grams (g) of Carbon, 2 moles (mol) of Hydrogen, 6.02x10 23 molecules of Oxygen, 22.4 Liters (L) of Nitrogen gas, and 15.0 milliliters (mL) of 2.0 Molar (M) Sodium Hydroxide). The lesson will then describe common numbers and units that students would see in everyday things (e.g., 1 gallon of milk, 2 dozen eggs, 12 square feet, 6 acres of land, 375 mL of water, 12.0 g of Chips, 2 eyes).

Linear and area models will be introduced. A careful introduction will be given to the students regarding not only how to place numbers on a number line, but that the numbers represent an origin and endpoint. With the area models, an emphasis will be placed on the fact that area models consist of congruent rectangles that, when subdivided in two directions, produce equal subrectangles of the whole.

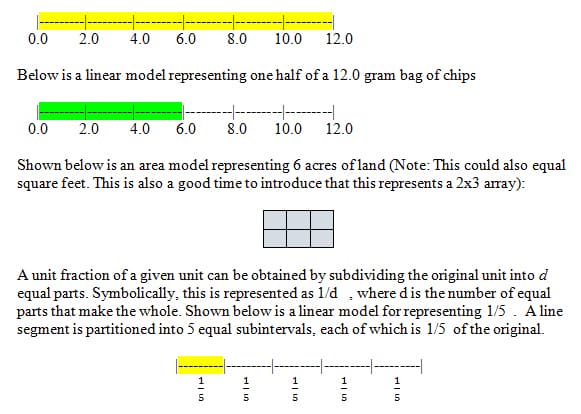

A linear model can be shown to represent one of these number and unit quantities, while an area model can be shown to represent another; this will be the opportunity to allay any misconceptions about how a linear or area model works. Shown below is a linear model representing one 12.0 gram bag of Chips:

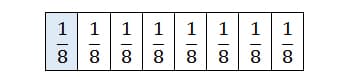

Use this to have students visually grasp that d sections (whether it be represented with string, rods, or algebraically) added up would equal one whole unit. With area models, the visual representations of unit fractions are similar. Below is an area model for representing 1/8. It is a rectangle, subdivided into 8 congruent subrectangles, each of which is 1/8 of the original. Note that, as with the linear model, the goal of this representation is to have students visualize that d copies of the unit fraction combine to make the whole. (Note: area models are easily represented with graph paper sections).

In all situations, one must be clear about what the whole or unit is; then 1/d is a part such that d copies of it make the whole. Before leaving the topic of unit fractions, students must be able to describe and defend an explanation of quantities that are unit fractions.

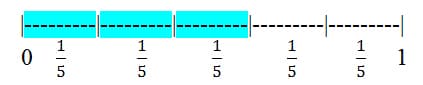

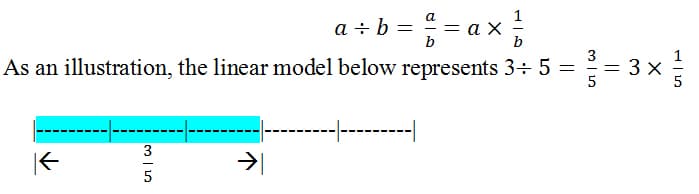

Unit fractions are special examples of fractions. The general fraction is gotten by taking a whole number, n, of copies of a unit fraction (1/d) and can be represented by the expression n x 1/d = n/d, where d continues to be defined as the number of equal parts required to make a whole 9. Shown below is a linear model representing the fraction 3/5, where 3 represents the n number of copies (n=3) of the unit fraction 1/5 , and thus can represent the rule of general fractions in the form 3 x 1/5 = 3/5 (Note: the slight spacing in highlighted sections represents its own copy of the fraction 1/5 )

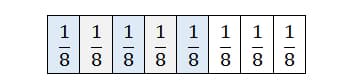

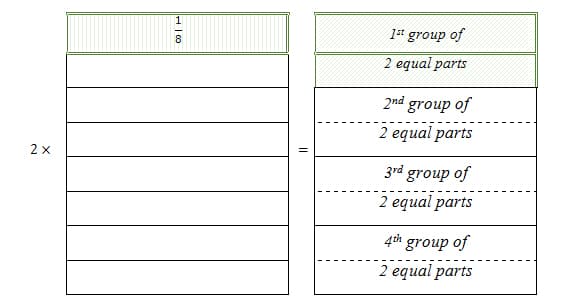

Shown below is the area model representing the fraction 5/8, where 5 represents the n number of copies (n=5) of the unit fraction 1/8 representing area, and thus can represent the rule of general fractions in the form 5 x 1/8 = 5/8 (Note: the variation in highlights are only to distinguish separate 1/8 unit fractions within the area model).

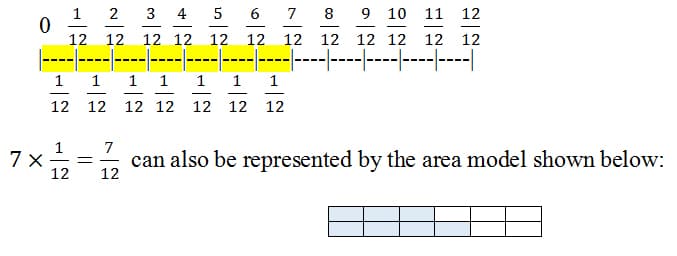

While students may want to pass over this part of the lesson quickly, it is imperative that they understand that this is a critical part of the unit. Students should be able to not only disaggregate a fraction into its unit fraction and its multiples, but they will need to be able to represent their fractions algebraically using the rule. Finally, students will be expected to find general fractions in real life scenarios, articulate them in sentence format, and present to their peers and the class. As an example to get the class started, the teacher can use the following example: There are 7 eggs left in my carton of 12 eggs. If my carton is taken as the unit, the fraction that represents this quantity is 7/12, where 7 = n number of copies of the unit fraction 1/12 (which here is one egg).This relationship can be represented symbolically in the form n x 1/d = n/d as 7 x 1/12 = 7/12 7, and can be represented in a linear model as shown below:

Students will have to create a unit fraction that can be related to some tangible object, create a sentence structure, describe the relationship algebraically, draw representative linear and area models, and then present their examples and models to their classmates. At this time, introduce the fact that unit fractions are present in abundance in measuring systems, where they appear as smaller units such as 1 cc = 1/1000 liters and 1 inch = 1/12 feet.

This lesson will conclude with the big idea that a fraction n/d represents a division a/b, where the numerator, a, represents the number of copies of the unit fraction 1/b, and the denominator, b, represents the equal number of parts to make a whole unit. Students should be given time to digest the idea that the fraction a/b represents the division of a number a divided by b equal parts 10

The area model below represents 20 ÷ 100 = 20/100 = 20 x 1/100 and can be understood by students to represent 20 cents, or 1/5 of a dollar. Have students create this representation with a piece of graph paper that measures 10×10. After students highlight the 20 congruent subsections, have them fold the paper at the bolded red lines. Allow students to recognize that 5 equal sections are created, representing 20/100 = 1/5.

This representation is significant in that it represents not only our units of monetary measurement, but our decimal system as well. In fact, the division of a fraction, when entered into a calculator, represents a conversion to the base 10 system where the d in a unit fraction of 1/d is represented in iterations of 10, 100, 1000, 10000, but when converted represents 1/10, 1/100, 1/1000, 1/10000, respectively.

Big Ideas of Lesson 2: Arithmetic of Fractions (+ and x)

Adding fractions with the same denominator is done by adding their numerators. This can be represented symbolically by the rule 11:

m/d + n/d = (m+n)/d

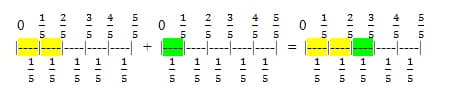

Students should be given linear and area models to help them visualize that this rule is correct. Below are two models. The linear model represents 2/5 + 1/5 = 3/5. Using the rule of addition of fractions with the same denominator, it can be written as: 2/5 + 1/5 = 3/5.

Below is the linear model representation of this expression:

When thinking about addition in the linear model, the general principle is that addition of lengths amounts to placing the lengths end to end; in the above example, the yellow lengths are placed end to end with the green lengths to amount to the total length of 3/5.

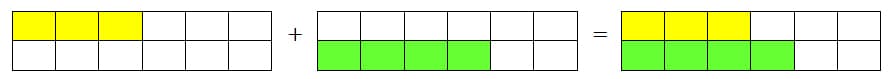

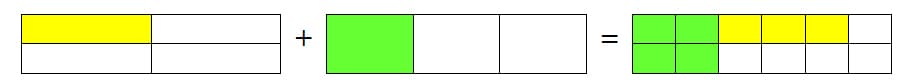

Below is an area model representing 3/12 + 4/12 = 7/12. This expression can be algebraically represented as 3/12 + 4/12 = (3 + 4)/12 = 7/12, and visually represented by:

Although the above diagram may be easily understood by the adults, allow the students to delve into the interpretation as to what the empty boxes represent. We don't add the empty boxes, because they are not actually there. Only the highlighted boxes are real. The empty boxes are drawn for purposes of comparing what we actually have (which are the highlighted boxes) with the unit (which here consists of one large box, or 12 small boxes). Further, if students recognize 3/12 = 1/4, or that 4/12 = 1/3, do not hold them back from exploring this idea. Show them the area model visualized below, explaining that we will be reviewing this in an upcoming lesson:

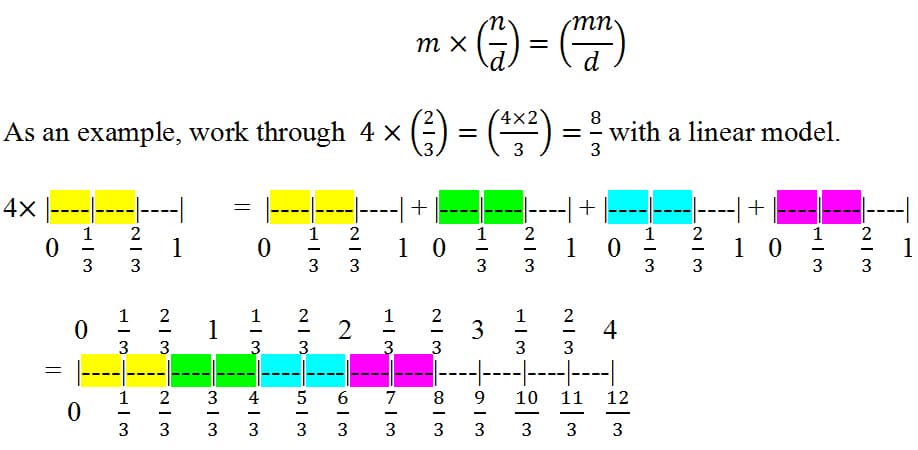

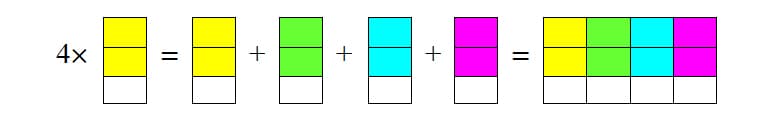

Two concepts will be reviewed regarding multiplication of fractions. First, the multiplication of fractions by a whole number will be explored by continuing to expand the rules. The algebraic representation will expand the rules from general fractions to visualize that the algebraic representation below 12 can be shown with numbers:

Ensure that students are grasping the principle of placing numbers on the number line. Further, remind them that by putting the length segments end to end, they can show the resulting total length segment. Here is an area model that shows the same product:

Make sure to discuss the models in sentence formats, and have the students do the same. Four of two-thirds is equivalent to four of two of the unit fraction one-thirds, resulting in eight of one-thirds. It is crucial to verbalize and think through the processes learned above out loud with our students, and to give them an opportunity to practice this as well.

Big Ideas of Lesson 3: Repeated subdivision, reconstitution, and renaming

This lesson will have students utilizing linear and area models. Students will justify their answers and persevere through their explanations of why the models work and how they represent their algebraic expressions. This is a critical part of the unit since the skillsets from these three rules are the basis for understanding proportional relationships.

Rule 1: Rule For Repeated Subdivision

The rule for repeated subdivision follows the same methodology as the previous rules of fractions. It is symbolically described as 13:

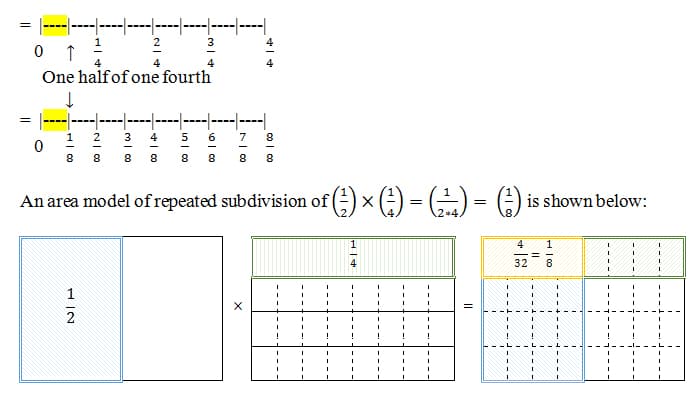

(1/e) x (1/d) = 1/ed

but at this point in the unit, should be described verbally and in sentences. The key is to relate this concept to real life quantities. For example, if we take half of a dime, we know that it represents 5 cents. We will work through examples like this to make the connections to the students. Since a dime represents 1/10 of a dollar (because 10 dimes of equal value represent the whole unit one dollar), (1/2 x (1/10) = (1/(2*10)) (1/20), algebraically represents one half of a dime, resulting in (1/20) of a dollar. Students can logically process that 20 nickels of equal value equal one dollar; based on our rules of unit fractions, we can represent (1/20) of one dollar as a nickel. Via models, numerical problems will also be worked out. For example, in a linear model, (1/2) x (1/4) = (1/(2*4)) = (1/8) and can be represented as follows:

Rule 2: Reconstitution

Reconstitution will be the next topic. The idea of reconstitution is that when a whole number that is a factor of the denominator is multiplied by a unit fraction such that:

E x (1/ed) = (e/ed) = (1/d), d groups are formed with e equal parts. Reconstitution is significantly easier to visualize with modeling. Seen below is an example of 2 x (1/8) = 2 x (1/(2*4)) = (2/(2*4)) = (1/4) , where there are 4 groups formed of 2 equal parts.

Another way of looking at 2 x (1/8) = 2 x (1/(2*3)), allows for an area model of 2 x (1/2)(1/4)

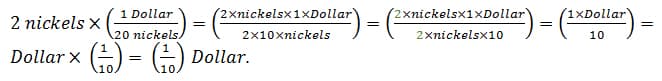

Although this is significantly easier to recognize visually, it is crucial that students get an understanding of how to manipulate these variables algebraically. The class should spend significant time translating from diagrams, especially area models, to symbolic expressions and back. This part of the lesson will have the students converting common things that they are familiar with. For example: 1 Nickel is equivalent to (1/20) of a Dollar. 2 Nickels are equivalent to 1 dime. Therefore, If we only knew these relationships, we could find out how many dimes are equivalent to 2 Nickels using the Rule of Reconstitution.

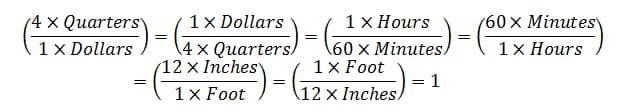

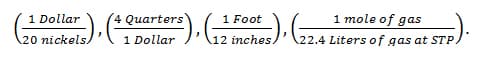

This is a critical example in that it will be the first example in which you demonstrate a unit as its own "entity" that must follow all of the rules of arithmetic that we have learned to this point. Rearrangement of the order of numbers and units in the numerator and denominator were rearranged in the example above to show that the rule of reconstitution applies. The term equivalent should also be reviewed to represent two numbers with units whose equivalent values are equal, and thus when divided by each other equal 1 without a unit. This can be algebraically represented with real life examples of money, time, and measurement; for example, 4xQuarters = 1xDollar, 1xHour = 60xminutes, and 1xfoot = 12xinches. However, when these equivalent values are divided in n/d format, we get an equivalent equal to a quantity of one with no units; a (pure) number is a ratio of like quantities. An algebraic representation that most students should be able to visualize is:

(Note: Give proper time to allow students to digest the idea that multiple equivalents in the n/d format equals one with no units)

Rule 3: Renaming & Introduction to the significance of following the rules with units

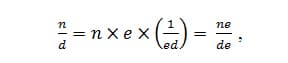

The rule for renaming is elegantly simple, and like the other rules, is a combination of the previous rules learned. One representation is 14

in which having the multiple of e/e can not only be used to find common denominators, but also to convert dimensional units. The process by which n/d = ne/de can be found by simply following the previous lessons in the unit. Given a unit fraction of 1/d , with a number of copies, n, of that unit fraction, x 1/d = n/d . If we reconstitute this fraction, we can represent an equivalent fraction n x (e x 1/de) = ne x (1/de). This symbolic rationale is explored to give the reader (teacher) an understanding of the logic sequence that must be understood by the adult learner. For the student, be sure to show how it makes sense in linear and area models, perhaps not even exploring the symbolic derivation. Introduce students to unit conversions in the form of fractions used in chemistry such as 1919

I want my students to learn that given any conversion, they can turn it into an equivalent fraction. They can then use that equivalent fraction to change the unit fraction from the units it is currently in, d, to the units that they wish to create, de. The conclusion of this part of the lesson should have students able to articulate why n x (e x 1/de) = ne/de when multiplying a whole number (n) or fraction (1/d) with an equivalent fraction e 1/e 2 , (whose numerator representation of number and unit, e 1 are equal to the denominator's representation of number and unit, e 2) merely "converts" the original number and unit n/d to a desired number and unit ne 1/de 2. This is the basis for Stoichiometry and should be given the appropriate time throughout the school year. The big takeaway from renaming is, that given any two fractions, you can rename them as fractions with the same denominator. Then if you want to add/subtract them or divide them, it is just like the corresponding whole number operations. Also, you can compare them. For multiplication, you don't need to rename, but the area model argument for computing the product uses the same moves – subdividing in one direction, then in the other – as the discussion of repeated subdivision, reconstitution and renaming.

Big Ideas of Lesson 4: Proportional Relationships

Proportional Relationships utilize all of the arithmetic rules that we have learned thus far. They are a certain kind of relationship between two different variable quantities (usually represented by x and y). In a real life scenario, a proportional relationship is said to exist when there is a constant k such that

y=kx.

The k factor is called the constant of proportionality. If this constant is always created when a relationship exists between the inputs (x) and the outputs (y), then x and y are said to exist as a proportional relationship. It allows us to create a relationship between two different values of the variables y and x. If x 1 and x 2 are two values of x, and y 1 and y 2 are the corresponding values of y, then y 1=kx 1 and y 2=kx 2. If we divide both sides of the first equation by x 1, and the second by x 2, we obtain the relationship

y 1/x 1 = k = y 2/x 2

Here the constant k appears as the ratio between any corresponding pairs of y and x. This is the symbolic explanation as to why proportional relationships are also sometimes expressed as the comparison of two equal ratios. If we divide the each side of the first equation by the corresponding side of the second equation, we get the relationship

y 1/y 2 = kx 1/kx 2 = x 1/x 2

In this relationship, the constant of proportionality seems to have disappeared, and instead we have a statement that y and x vary at the same proportional rate: if x doubles (x 2 = 2x 1), then y also doubles (y 2 = 2y 1), and similarly for any other proportional change. However, the constant of proportionality can be recovered from the equation y 1/y 2 = x 1/x 2 by multiplying both sides by y 2 and dividing both sides by x 1. This recovers the

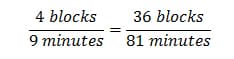

Relationship y 1/x 1 = y 2/x 2. If we think of x 1 (and hence y 1) as staying fixed, and x 2 as varying over all possible values of x, with y 2 varying accordingly, then this equation says that the ratio y/x does not change, i.e., it is constant. That constant is k. After giving this basic definition of proportional relationships, be sure to give several examples, and discuss carefully why they are proportional relationships. For example, if you can walk 4 blocks in 9 minutes, then at that rate, how many minutes will it take to walk 36 blocks?

Another example of a rate proportionality can be applied to the concept of driving at constant speed. Have students talk through a scenario of a driver going 50 miles per hour (mph). Discuss what it means that to drive at "constant speed", allowing your students time to realize that it means you cover equal distances in equal times, or more carefully, that in any two equal time intervals, you go the same distance. So if the driver is going 100mph, then in the first half hour and the second half hour, you cover the same distance, and two of that distance makes 100 miles, so you travel 50 miles in half an hour. And in any quarter hour, you travel 25 miles, and so forth. If you follow this through, you conclude that in x hours, the driver drives 100x miles, at least when x is rational. But perhaps you may just want to declare that driving 100 miles an hour means that he drives 100x miles in x hours. Assuming he does not get pulled over or wreck, how long will it take to drive 50 miles?

The statement that "he drives at a constant speed of 100 miles per hour" means that, in driving for x hours, he goes d = 100 x miles. So asking how long it takes to go 50 miles is asking for the x that satisfies

100x = 50.

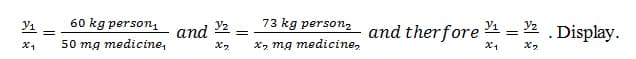

Dividing both sides of this equation by 100 gives x = 50/100 = 1/2. The miles traveled and hours driven are the variables, with "100" representing the constant in the proportional relationship between them. Students will practice various proportional relationships including drug conversion problems, and molar ratio problems. For example, if a 60 kg person should take 50 mg of medicine, how many mg of medicine should a person take if they weigh 73 kg? Make sure to state the fundamental assumption that the correct level of medication is proportional to weight. Then point out that, in this case, we are not given the constant of proportionality, so we have to use the second formulation of proportional relationship y 1/x 1 = k = y 2/x 2. In this example, the setup would let

Students will then solve for x.

Big Idea of Lesson 5: Principles of Drug Dosages

Basic information of Pharmacology will be reviewed utilizing units prepared by the FDA 15. FDA regulations regarding OTC Drug labeling will be reviewed. This lesson will also rely on the online review activity created by the FDA which will review common symptoms and relief terms, what drug labels must disclose, and other critical terms such as active ingredient, and strength per dosage type 16. Explain to students that, although it is not strictly true, a good rule of thumb is that drug dosage for someone of a given age should be proportional to weight. Then provide a list of constants of proportionality for various age bands, or to be sometimes more challenging, give the appropriate dosage for someone of a given weight, and ask your students to find the constant of proportionality 17.

Big Idea of Lesson 6: Creating your dosage chart ~ Culminating Activity

The goal of the unit is developing this chart. To make their personal chart, students will take the weight measurements and record the age of all members of their household. Students will also record on their chart the appropriate information (based on the template provided in Appendix B) from each of the OTC drug medications that may be used in their household. Students will then calculate the appropriate dosages for all of the OTC medicines on the chart. Appendix B has not been provided as a comprehensive chart. Rather, it has been provided as a guide to serve you in determining what information needs to be recorded in the students' charts; included in the appendix are common OTC medications that have single and multiple active ingredients. It is recommended that ALL recommended dosages be reviewed via the manufacturer's websites at the time of the unit. Please also note that separate dosage charts should be created for infants, youth, and adults. After you are confident that the students have accurately transcribed the information from their household OTC medication packages, have the students conduct a peer review to look for possible mistakes.

Once the charts are created, have students begin calculating their household's dosages. The key to this section is that the students are going to have to describe carefully the steps that they took to come to their final answers. They must explain their reasoning in writing. Also, students will have to defend their answers, as well as explain the process of the mathematics, and why the conversions work to the class. Finally, after peer reviews, students will write their calculations with explanations on the back of their poster so that they can refer to their chart calculations for future modifications.

Comments: