Classroom Activities

Part One: Introductory Portion of Unit

Magritte’s Pipe Opening Assignment

To show the relationship and/or power balance between words and images, “The Treachery of Images” by René Magritte in 1929 is a great place to start. This discussion can be facilitated by a See Think Wonder as explained in the previous section. However, the most important part of this activity is setting up the importance of the influence text can have on image and vice versa. This begins to explain the interplay between the two. Facilitating the discussion on text, image and the image-text here can be tricky. It is a great time to draw some lines for the students. They see the image of the pipe. They see the text at the bottom. They also see it together. At this point, defining the combination of image and text here could be helpful. When text is alone, it is linguistic. When image is alone, it is strictly visual. When the two are combined in any way, referring to them as an image-text will clarify things. This allows for a clearer path to the conversation previously mentioned in Content Objectives about Scott McCloud and iconology.

Hieroglyphics to Emoji: The Evolution

Within the first few days of the unit, you want to start drawing connections between the past and present. There are various ways to do this mentioned above. However, after some lecture and discussion, one of the more creative and entertaining ways to do this are having students communicate with hieroglyphics (very primitively) and emoji. Online you can find easy “how-to” hieroglyphic alphabets and websites that translate for students so they can write out their names and construct short messages to one another.

Then, I suggest you have the kids work in Google Docs for the next step. Have the students pair up and create a script of a conversation composed of emoji only. Google Docs has an emoji keyboard they can utilize. Have the students click on Insert>Special Characters>use the drop down menu to select Emoji. There they will find various screens of themed emoji. With both students on the Google Doc at once, they can collaborate and respond to one another. The exercise in using both forms of communication should solidify some connections between past and present. A free write or exit slip on the similarities and differences between the two modes of communication could become a great brainstorm for the larger project throughout the year.

Here is an example of doing this on a smaller scale with basic identity. My name is hieroglyphics is what appears to be a bird, knife, and upside down top hat according to translation alphabet found online. To express myself in emoji, I may put ♓ 🏫 🚺. Discussing the similarities and differences between these two expressions of my identity will be fruitful.

Introducing Literary Criticism

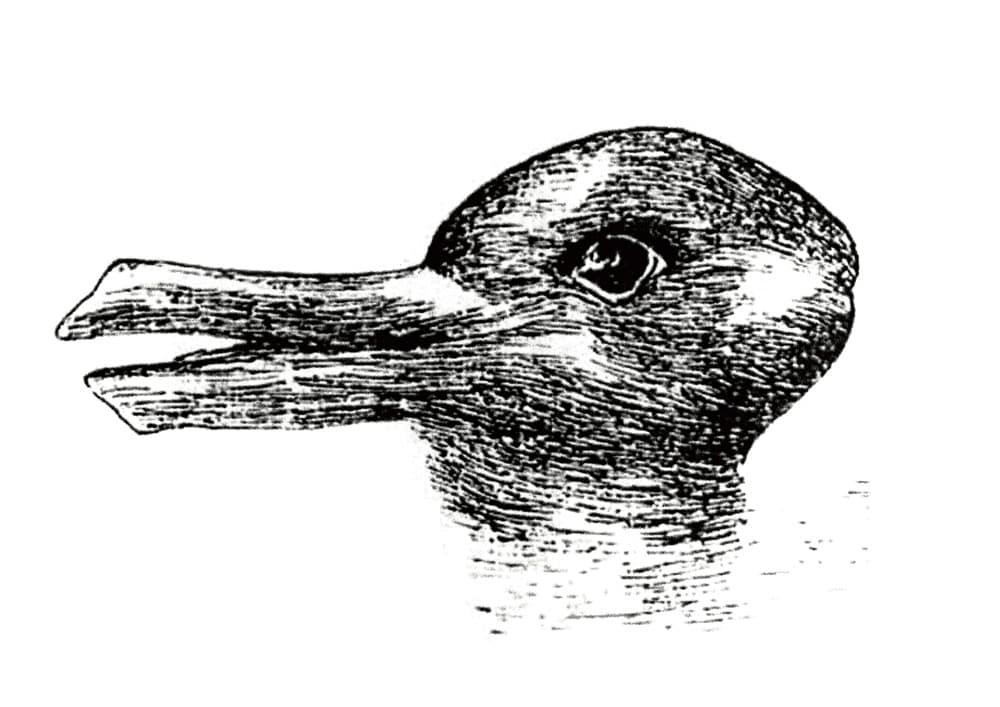

Figure Duck-Rabbit illusion. From: Jastrow, J. The mind's eye. Popular Science Monthly, 1899. Artist: Jastrow, Joseph (1863-1944)

Literary criticism is not an easy concept for students. To introduce the students to the concept, I make it all about perception starting with a bellringer where I give them a folded up piece of paper with the famous rabbit-duck illusion (Figure 2). When everyone is seated, I have them open up the folded paper and write down what they see. Some see the rabbit and some see the duck. The floor is now open to talk about perspective--why do some of us see the duck while others see the rabbit? The conversation can go in a variety of directions. One of the most common is the discussion on where your eye goes first. Did you see a beak or ears first? I then guide the conversation to a variety of sayings and adages that they are familiar with: is the glass half full or empty (i.e. pessimism or optimism)? What does it mean to look at the world through rose-colored glasses? We then look at a variety of illusion paintings and images to further examine perspective. When they are ready to talk about the four lenses that we will be focusing on (feminist, Marxist, archetypal and reader response), we return to the question of what it means to look at the world through rose-colored glasses? What if those glasses were green for money, black and white versus color, or didn’t allow you to see gender? How do those concepts change the way you view the world?

Figure 3 “Globe” of Flags

Then, it is time to introduce the basic tenets of those four literary criticism lenses. With each lens, I give the students an image depicting that lens. For example, when we discuss the feminist lens, I give the students a picture of Rosie the Riveter and for reader response I display a stick figure walking towards a book with a suitcase--what do we, as readers, bring to the texts we encounter (i.e.-biases, perspective, etc.). After we have gone over the basics of the lenses, I give the students an image of a “globe” of flags (Figure 3). I then ask the students to do a See Think Wonder. As a class, we do the See and Think aloud some basic observations are expressed. Then, I number off the students to have them wonder about the image via a specific lens we discussed. If I have the Marxist lens, my “wonder” will revolve around the economy of those countries’ flag and which flags represent the wealthy, powerful countries and which are the poorer, underdeveloped countries. Similarly, the feminist lens will wonder about the role women play in each country and so on. This is their first taste of literary criticism.

Within the next few days, I will grab various images from disparate forms of art (painting, sculptures, photography, clip art, etc.) to post around the room. The students will do a gallery walk analyzing the various images using See Think Wonder. The important part of using this technique is that it slows down the eye. It makes the students thoroughly look at the image, think about its author/significance/message/meaning, and finally wonder through one of the literary criticism lenses. I repeat this activity with song lyrics, video clips from movies, advertisements, and eventually various types of poetry and prose. Throughout the school year, students use the See Think Wonder method to analyze images, videos, texts and image-texts.

Part Two: Thread Component throughout the Curriculum

Example Week One Activities throughout the Year

Week one of each unit throughout the year will have two goals. First, this week needs to introduce the historical background for the literary period. This can be delivered in a variety of ways. Personally, I like to lecture a little on the political and social conditions of the time and biographical information on that unit’s main author(s) with some guided notes and also include a short educational video on the time period. After some basic groundwork on the time period and author, you can move into introducing the image or image-text from this time period that will lead into the larger text for the unit. Along with this, you will be introducing the form of analysis that you will focus on in the larger part of the unit. The chart listed in the Content Objectives section of this unit plan gives examples of the larger text and the unit’s introductory image-text.

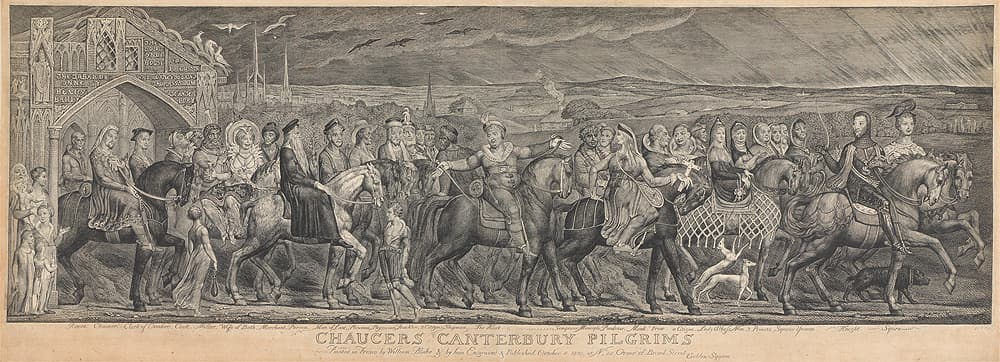

For instance, in the unit after the introductory unit to setup the year, the students are studying Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer. The larger unit focuses on characterization and point of view. For the introductory image-text, we will be looking at the pilgrim portraits of Chaucer’s characters by investigating images from the ancient manuscript. The pictures of the manuscripts can be found on the Huntington Digital Library or the Luminarium: Anthology of English Literature to have your students look at online or to print for them. In addition, I also want my students to examine William Blake’s Chaucer’s Canterbury Pilgrims (Figure 4). As we will start every unit, the students will use See Think Wonder to first investigate the manuscripts. There are not many pictorials in the “General Prologue” so skipping to the actual tales will allow for more fruitful conversations. I would suggest assigning the students tales to investigate-- specifically the tales you plan on covering. For my class, the students will read the “Pardoner’s Tale” and “Wife of Bath’s Tale”. For the most part, there are images on the manuscript for each tale’s pilgrim. While doing the See Think Wonder, students will begin to make predictions about the characters and the story. They cannot read the text in the manuscript because it is in Middle English, so they really have to depend on the visual.

Figure 4 Chaucer’s Canterbury Pilgrims by William Blake (Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection)

However, the pictorials of the characters are not the only thing you want the students to focus on. To truly take in the literary tradition of the time, the students are also recognizing it is handwritten, the foreign form of English, the ornate lettering at the beginning of tales, the comments in the margins, the beautiful colors being used, and much more. This opens up a conversation about how this is related to the hieroglyphs on ceramics, monuments and cave walls talked about previously. Making these connections in the week one activities is very important.

Furthermore, one of the areas for analysis for this unit is characterization, so we use an acronym for student’s to remember the tenets of characterization--STEAL. It stands for analyzing a character’s speech, thoughts, effect on others, actions and looks. Taking the depictions in the manuscript starts to develop one of those tenets. Then, I think that comparing the pictorials in the manuscript with Blake’s Chaucer’s Canterbury Pilgrims is an interesting area of investigation. Match that conversation with the physical descriptions in the “General Prologue” about each pilgrim and you are including other tenets (actions, looks, effect on others) of characterization. Moreover, when the actual tales begin to be told, even more about the pilgrims evolves. Using these introductory texts to ease into the unit’s larger texts is a great tool.

Briefly, another example of a way to use the image-text that is a little different than the example above is using Scott McCloud’s illustration of Robert Browning’s “Porphyria’s Lover” to introduce Victorian poetry. Scott McCloud’s website gives an image paired with each line of the poem. I think it is an interesting way to look at a modern interpretation of a Victorian poem. The illustrations will not only aid the students through the poem but also provide plenty of discussion on the interpretation and plot.

Additionally, for a Shakespeare unit, you could use the stage production as an introductory image-text. One of the most important things to remember while teaching plays in the English literature classroom is that plays are meant to be visual. At my school, the students read a Shakespeare play each year. To introduce this unit, I am going to show clips of last year’s play Romeo & Juliet. This will give me a chance to disseminate some background information on the Globe Theater and society as Shakespeare knew it while doing so using a text familiar to them. I would also take time to connect Shakespeare’s works back to the democratization of knowledge talked about at the beginning of the year because it is the first time in England’s history that people other than the upper class experience the amazing world of the theater. This idea should resonate with the similar events such as the birth of the Gutenberg printing press and social media platforms. Again, keeping these connections to other parts of literary history and to the student’s life of today are vital to the success of this unit and the course thread in general.

Year Long Project

Throughout the year, the students will be collecting See Think Wonders and other journal writings on the images, texts, and image-texts they examine and analyze. All of these will prove very fruitful when students actually sit down to think about how they want to answer the essential questions: How has image affected the way we analyze text over history? Furthermore, what is the best medium to express a complete answer to this expansive question? These will all be kept in their binder for safe keeping. In addition, all the websites of our analysis pieces will be kept online in our Google Classroom. As said before, everything for this year long assignment will be done in the G Suite (Google Docs, Slides, Forms, Sheets, and Classroom).

The timeline for the assignment will be spread over ¾ of the year. The first quarter will be spent acclimating ourselves to the SOI and essential questions for investigation. This will include but not be limited to the See Think Wonders, journals, image-text creation, class discussion, etc. Quarter two will be the beginning of rough draft creation of the student’s assignment. This can be done in a variety of mediums including but not limited to majority prose, majority image, comic book format, mixed media, digital media, or otherwise. This will also be the time that student-teacher conferences occur and some narrative about your upcoming project will be discussed. The third quarter should be dedicated to revising your creations from quarter two by peer editing and conferencing with peers. Finally, your assignment should be ready for assessment by the middle of the 4th quarter.

Comments: