Content Objectives

How We Taste Foods

As one of the five senses, taste plays a major role in the enjoyment of food. From a biological perspective, taste has helped humans find edible items to consume. Taste buds are capable of detecting sour, bitter, salty, and sweet tastes. Sour tastes are derived from acidic foods such as lemon juice or vinegar. A number of sodium and chloride salts are responsible for salty tastes, whereas sugars provide the sensation of sweetness. Alkaloids, such as caffeine, produce bitterness. Many alkaloids happen to be poisonous, and this may be why bitter notes in foods produce a strong negative response in many people.2 It is widely believed that a fifth taste, known as umami, exists. Described as savory, umami is derived from the Japanese word for this taste and is found in foods such as tomatoes and parmesan cheese.3

Taste buds serve as the detectors for taste, and thousands of them can be found along the tongue and on the hard and soft palates of the mouth. While it was previously believed that taste buds detected a particular taste and were located in a specific region of the mouth, it is now understood that taste buds may detect a range of tastes to varying degrees. What the brain registers as taste is really a cumulative response from all of the taste buds.4 Scientists are working to deepen their understanding for how taste buds function, but it is known that they detect tastes when the chemicals in foods bind to the cilia, or fine hairs, of a taste bud. These flavor molecules, which must be in a liquid such as water or saliva, provide a taste sensation. The mechanical process of chewing will release additional flavors as the enzymes in saliva react with the food to create new molecules that contribute to a flavor profile.5

The ability to taste food is further developed by the sense of smell. It is estimated that a staggering 80 percent of flavor is derived from odors that are smelled.6 Humans are capable of detecting a scent when as little as 250 airborne molecules encounter a few dozen cells in the nose.7 A flavor profile could have a chemical composition of hundreds of molecules, but only a few in very low concentrations may be responsible for the flavor’s essence.8 While it may be surprising that smell plays such a substantial role in tasting food, the back of the mouth does contain a connection to the nasal passage. It is at this juncture where olfactory cells detect the smells that contribute to the perception of flavors. Initially the smallest molecules are detected, and with chewing, larger molecules enter the nasal cavity. It is interesting that the sensitivity of noses is not universal. For instance, 40 percent of men and 25 percent of women are unable to detect the scent of truffles, and as a result, they are unable to experience the full flavor profile of this costly ingredient.9 Scientists believe that the variance among an individual’s nose sensitivity is one contributing factor for the diverse food preferences that people develop.10

The Scientific Classification of Sugar

Sugars are used by living things to store energy, and they belong to a broad family known as carbohydrates. These molecules generally adhere to a 2:1 ratio of hydrogen to oxygen which is identical to the chemical structure for water.11 When they dissolve, they taste sweet and contribute four calories per gram. It is interesting to note that sugars do vary in their perceived levels of sweetness. This has potential nutritional implications as a lower quantity of a highly sweet type of sugar can be substituted for another to provide the benefit of having fewer calories without compromising taste.12 While sugar is colloquially used as a generic term to reference a crystalline substance that is sweet, there are actually numerous sugars that exist.

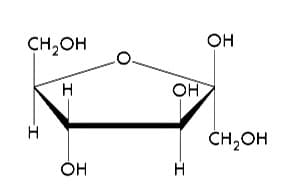

Sugars are classified based on the number of ring structures they contain. These ring structures are known as saccharides.13 Monosaccharides contain one ring structure and are commonly known as simple sugars. A common monosaccharide is fructose, which is the sweetest of the naturally occurring sugars. An interesting property of fructose is that it is highly soluble, meaning it is easily dissolved in water.14

Figure 1: Molecular model of fructose. Unless otherwise marked, the vertices of the pentagon are carbon atoms. 15

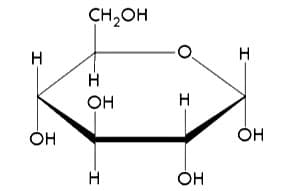

Glucose is another common monosaccharide, and it is the building block of complex carbohydrates.

Figure 2: Molecular model of glucose. Despite having the same chemical formula as fructose, they are different monosaccharides. Observe how their molecular structures vary.16

It is interesting to note that both glucose and fructose share the same chemical formula, C6H12O6, but are different monosaccharides due to the variance in the geometric arrangement of their molecular structure.17

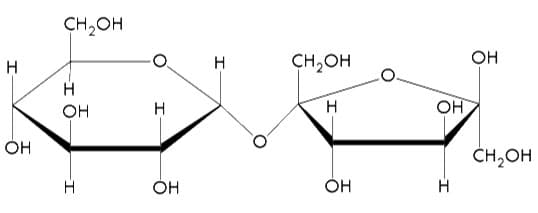

Disaccharides are two monosaccharides that are joined together. A common example of a disaccharide is sucrose, which is the molecule that is typically associated with the term “sugar”. This white crystal is composed of one fructose bonded to a glucose.

Figure 3: Molecular model of sucrose. Notice how a glucose is bonded to a fructose molecule.18

Lactose is the disaccharide that occurs in the milk of mammals, and its concentration will vary depending on the mammalian species. For instance, cow milk contains 4.5 percent lactose whereas human milk contains 7 percent lactose.19 Maltose is another common disaccharide, and this sugar is created during the malting of grains, specifically barley.20

Polysaccharides are larger sugars typically arranged in a chain. Known among scientists as glycans, polysaccharides can be quite large and may be composed of thousands of monosaccharides joined together.21 A significant number of polysaccharides are possible as monosaccharides can be arranged in any order, and these resulting combinations produce different molecules.22 Another factor contributing to the large universe of polysaccharides is that hydroxyl groups, (the components of the sugar composed of a hydrogen bonded to an oxygen), can be joined to different sections of each simple sugar’s ring.23 These changes produce different geometric arrangements of the molecule which means each iteration is a different polysaccharide.

Plants produce a couple polysaccharides that are relevant to a discussion on cooking. Cellulose is a polysaccharide that is created by plants to provide strength and structure to their cell walls. It can range in size from approximately 7,000 to 15,000 monosaccharides.24 Cellulose has internal hydrogen bonds that lead it to form chains that are highly ordered. Its linear shape causes cellulose to pack closely together and this makes the molecule both stable and insoluble.25 Humans, and most animals, are unable to break apart the bonds within cellulose for digestion. This property is what makes it an important source of dietary fiber.26 Termites and cattle are among the few animals capable of digesting cellulose as they contain bacteria in their guts that process this polysaccharide.27 Starch is another plant product that plays a significant role in cooking. Used by plants to store energy in the form of small granules, starch is really composed of two polysaccharides - amylose and amylopectin. In contrast to cellulose, starch has fewer internal bonds and this leads it to have a more open and spiraling configuration. When packed together, it does so in a weaker and looser fashion leading it to serve as an energy source for both plants and animals.28

Releasing the Energy of Sugars

A combustion reaction allows humans to consume sugars as a source of energy. Enzymes facilitate this process in the human body by converting the sugars into usable forms. Each enzyme is uniquely matched to its respective sugar, and humans are capable of digesting most monosaccharides and disaccharides.29 For example, sucrase is the enzyme that allows for the digestion of sucrose. Other carbohydrates that humans can digest for energy include lactose and starch.30

Humans lack the enzymes necessary to process large sugars, and a couple of these have interesting implications. Raffinose is a polysaccharide used by plants to store energy in seeds and beans. When humans consume this sugar, it cannot be digested until it reaches specific bacteria in the colon. A result of this process is carbon dioxide gas which can lead to awkward social interactions.31 The disaccharide lactose is digested when it reaches the lactase that lines the walls of the small intestine. For individuals missing this enzyme, lactose will not be digested. It then proceeds to the large intestine where it becomes lactic acid. This leads to the cramping and abdominal discomfort that characterizes lactose intolerance.32

Sugars Used in Cooking

Sucrose: Commonly Known as Table Sugar

Sugarcane is one of the primary sources for refined sugars that are used in cooking. There are in fact six species of sugarcane, and they are all grasses that belong to the Graminaea family. Of the species used for sugar production, Saccharum officinarum is the most widely grown. When at full maturity, its stalks have a height of fifteen feet and can reach a maximum thickness of two inches.33 Sugarcane has an approximate sugar content of 13 percent in its fluid, an atypically high amount that makes it an ideal candidate for sugar production.34 Within eighteen months of its first planting, sugarcane will reach its full maturity. Sugarcane can grow again after being harvested, but it will become progressively less productive. After several seasons, it will ultimately need to be replanted.35

An extensive process is utilized to refine and produce sucrose. In a sugar mill, harvested sugar cane is shredded and pressed to extract sugar cane juices. These juices contain a variety of compounds such as tannins, carbohydrates, and proteins which must be filtered out as they affect sugar's taste.36 This is achieved by clarifying sugar using heat and lime, and then boiling it until the solution thickens into a syrup. The evaporating water creates a sugar solution that is very concentrated. It will eventually reach a point where the sugar can no longer be held in solution, and the sugar will precipitate as crystals. This mixture is then spun through centrifuges to drive off the remaining liquid from the crystals. At this point, the sugar is wet and brown. It also contains a variety of miscellaneous items such as fiber, soil particles, and yeasts. Two additional purification cycles that follow the aforementioned process occur in a refinery.37 Granular carbon is added and works to decolorize the sugar by behaving like activated charcoal. The final crystallization process makes individual sugar crystals of uniform size, and yields a sugar that is 99.8 percent pure.38

In 1747, a Prussian chemist was able to extract sugar crystals from the juices of white beets. The purity of the crystals, and the average yield from a white beet, were comparable to that of sugarcane.39 This discovery remained largely dormant until 1811 when the French, out of economic necessity, applied the technology to lessen their dependence on sugar from British colonies.40 Using sugar beets to produce sucrose is comparable to the refining process utilized with sugarcane. One exception is that sugar beet refineries have an additional challenge of removing the impurities from the beets that produce foul tastes and smells.41 In the United States, sucrose is refined from both sugarcane and sugar beets. Temperate climates, such as those of Minnesota, produce sucrose derived from sugar beets. Tropical climates, such as those found in Florida, produce sucrose extracted from sugarcane. Current domestic production of sucrose from sugar beets is 55 percent with 45 percent of domestic sucrose originating from sugarcane.42

Molasses

Molasses is one of the byproducts of the sucrose refining process. Different grades of molasses are produced when the centrifuges separate the liquid (which is the molasses) from the crystallized sugars during each purification cycle. Each cycle produces a successively darker molasses with diminishing taste appeal. The first boiling produces a light molasses that is commonly used as table syrup.43 The second boiling darkens the molasses, but it is still palatable to humans. The final cycle produces the darkest molasses, commonly known as blackstrap, which is typically used in animal feed due to its concentration of minerals. Despite popular claims touting the nutritional benefits of molasses, it should be noted that they are insignificant. In a tablespoon of blackstrap molasses, the most concentrated form, there is only one-thirtieth of the daily recommended intake of vitamin B. Iron and calcium are both at one-sixth of their daily allowances. The lighter molasses contains approximately half of the aforementioned nutrients.44

Corn Syrup

Corn syrup is made by treating corn starch with an acid or an enzyme. The result is a syrup that contains glucose and maltose. The proportion of these sugars within the syrup are contingent on the extent to which the chemical reactions with an enzyme or acid are allowed to proceed. Advanced progression of the reaction will yield more glucose and maltose making the syrup sweeter.45 When all of the starch is converted into glucose, this can be known as “dextrose” due to its ability to bend polarized light to the right when in a solution.46 These dextrose molecules can be rearranged using an enzyme to become fructose. These are also known as “levulose” since they will bend polarized light to the left when in a solution.47 Corn syrups with a high fructose content are used by the food industry to sweeten products such as soft drinks. The reaction between corn starch and the enzyme can be diminished to allow for the preservation of longer sugar chains. The resulting syrup will be more viscous as the chains become entangled and prevent the motion of other molecules.48 Thick corn syrups are used to make foods chewy, and they also assist in preserving foods by reducing moisture loss.49

Other Sugars

There are several other sugars that are commonly used in cooking. Superfine sugar has very tiny sucrose crystals that have the functional ability to dissolve quickly.50 Brown sugar is typically made by lightly coating white sugar crystals with molasses. It can range in color from light to dark brown. Since brown sugar traps air between groups of crystals, it should be packed down before measuring.51 Powdered sugar is sucrose that is ground very finely. To prevent clumping, it often contains 3 percent cornstarch.52 Honey is the sweetener that ancient human civilizations used in foods before refined sugar was developed. It is composed primarily of fructose, glucose, and water.53

Synthetic Sweeteners

A variety of synthetic sugars exist that serve to produce sweetness. They primarily are used as substitutes for sucrose to limit consumed calories, or to reduce costs in food production. Saccharin is a sweetener that was first discovered in 1879, and it is perceived to be 200 to 700 times as sweet as sucrose. Many individuals claim it has a metallic aftertaste. It also happens to be calorie-free as it is not absorbed by the body to be used for energy.54 At one point, saccharin was linked to a study that indicated it increased the risk for cancer in rats. After a series of legislative battles and FDA proposals, the federal government declared in 2001 that there was insufficient evidence for the carcinogenic effects of saccharin in humans.55 Aspartame was accidently discovered in 1965 when a chemist observed that his fingers were sweet from a combination of aspartic acid and phenylalanine. While it does possess the standard four calories per gram, it has a perceived sweetness to be 160 times that of sucrose. This allows less aspartame to be used when it substitutes for sucrose.56 Certain individuals with a rare medical condition called phenylketonuria must limit their intake of phenylalanine. This is why products that use aspartame must come with a warning label.57

Current trends are encouraging the development of other sweeteners with no added calories. In 1999, sucralose gained federal approval to be used as a sweetener. At 600 times as sweet as sucrose, minimal amounts can be used. Sucralose also provides an additional benefit of contributing no calories as it is not broken down by the body.58 Strong societal demand continues to exist for sucrose alternatives to have more natural origins. The food industry has recently turned to the leaves of the stevia plant which contain steviol glycosides that are 100 to 350 times as sweet as sucrose. Similar to prior sweeteners, this product is stymied by claims that it leaves a bitter, metallic aftertaste.59

Chemical Behaviors of Sugar

Solubility of Sugar

One of the unique properties of sugar is that it is highly soluble, or dissolves easily, in water. To better understand this chemical behavior of sugar, here are a few key ideas about water. Within a water molecule, two hydrogens are bonded covalently with oxygen. In covalent bonds, two atoms share electrons through an overlap of their electron clouds. The geometrical shape of a molecule depends on the types of atoms bonded together. This is significant because a molecule’s shape affects how it interacts with other molecules.60 In the case of water, the covalent bonds lead the molecule to form a shape that resembles the letter “v.”61 Imagine an obtuse angle with a measure of 105 degrees where the oxygen is serving as the vertex, and the hydrogens are points on the respective rays. Different atoms have different affinities for electrons which influences the chemical properties of the molecule. In water, oxygen has a stronger affinity for electrons than hydrogen, thus producing a slightly negative charge around the oxygen. The area surrounding both hydrogen atoms is slightly positive as a result. This uneven distribution of charge and the associated geometry of the covalent bond results in water being a polar molecule.62 In addition to the covalent bonds within a molecule of water, hydrogen bonds exist between individual molecules of water. Hydrogen bonds are attractions between a hydrogen with a slightly positive charge to an atom with a slightly negative charge. These bonds are common in nature and are sufficiently weak to result in frequent rearrangements of the hydrogen bonds.63 The behavior of hydrogen bonds contributes to water’s fluid nature.

There are several characteristics about sucrose that, when combined with water’s polarity, allows it to be highly soluble. Similar to water, sucrose has covalent bonds between oxygen and hydrogen, and this results in polar molecules. Additionally, its molecular structure contains hydroxyl groups (-OH) that stick out to permit the formation of hydrogen bonds with water.64 When this occurs, a molecule of sugar is dissolved. Sucrose is also capable of squeezing into the open lattice framework created by the shifting hydrogen bonds among water molecules.65 It should also be noted that given equal volumes of sucrose and water, there will be fewer molecules of sucrose. When comparing one cup of sucrose to one cup of water, there will be one twenty-fifth as many sucrose molecules as there are water molecules.66 The larger number of atoms in sucrose leads it to occupy more space which results in fewer molecules being present. This means there are vastly more water molecules available to form the hydrogen bonds that will dissolve the sucrose molecules.

Hygroscopic Property of Sugar

Sugar is a hygroscopic substance which means it is able to attract water or moisture from its surroundings. The reason for this is similar to why sugar is so soluble in water - the hydroxyl groups will easily bond with water. Sugar’s hygroscopicity allows it to have a variety of practical applications in cooking. When baking, sugar helps baked goods retain moisture. This allows for the production of moist cookies and cakes.67 Sugar also will help finished baked products draw in moisture from the air to remain tender and fresh.68 When making ice cream, sugar helps to prevent the formation of large ice crystals.69 It does this by helping to lower the freezing temperature of water past 32 . This allows for the rapid formation of very small ice crystals that provide frozen treats with a texture that is perceived to be smooth and creamy.70

Caramelization

Caramelization is a complex process that results in the browning of sugar to produce rich, deep, and complex flavors. It begins with hydrolysis, a reaction that involves heating a sugar with water. In this reaction, the water reacts with the oxygen atom that is joining a disaccharide or polysaccharide together and breaks them into their constituent simple sugars.71 Using sucrose as an example, hydrolysis will break it into glucose and fructose. There will also be the loss of a water molecule.72 When this solution is heated further, a degradation reaction will occur. This means that the sugar rings will open, and will result in the formation of new molecules.73 These chain-like molecules are known to be acids and aldehydes.74 As the reaction proceeds with the continuous application of heat, the solution will change from a clear liquid to successively darker shades of yellow that will eventually become brown. Polymers are forming at this stage that produce the characteristic brown hue of caramelization. Scientists are still investigating the complex reactions that occur during caramelization, but it is believed that the chemical bonds are altered in a way that causes them to absorb light and create color.75

Maillard Reactions

When sugars are heated in the presence of proteins, a series of complex reactions occur that are collectively termed Maillard reactions. Credited to Louis-Camille Maillard, a physician fascinated with biochemistry, this type of browning is responsible for the flavors found in foods such as bread crusts, soy sauce, chocolate, and roasted meats.76 Scientists are still studying Maillard reactions, and their complexity is the result of a variety of sugars reacting with numerous amino acids (the building blocks of proteins). Additionally, the products from the reaction of any given sugar and amino acid pair are contingent on temperature.77 These permutations allow for the possibility of numerous flavors.

One of the prerequisites for Maillard reactions to occur is that extremely high temperatures must exist. The application of heat degrades sugars and amino acids into smaller sugars and amino acids. The sugar rings open and aldehydes and acids react with amino acids. At this point, a spectrum of chemicals is developed. These molecules react with each other, and new flavor compounds emerge.78 When cooking meat, this happens on the surface with frying, roasting, baking, or broiling. Due to the water content in a piece of meat, the temperatures in its interior can never exceed the boiling temperature of water. This inhibits the extreme temperatures necessary for browning to occur. The need for high temperatures is also the reason why foods that are boiled will never brown.79

History of Sugar

Used for centuries by human societies, sugar has a dynamic past. Sugar was originally refined in India around 500 BC, and the technique was brought to the Middle East by traders. It was initially introduced to Spain by conquering Arab armies, and was later spread throughout Europe by returning Crusaders.80 The Spanish and Portuguese introduced sugarcane to the New World through the construction of sugar plantations on their colonial holdings. It was Christopher Columbus that first planted sugarcane in the West Indies during his second voyage in 1493.81 With expanding naval prowess and ambitious imperial designs, the British established colonial outposts in North America. One result of Britain’s expanding empire was the creation of sugar plantations in the Caribbean that eclipsed those of their Iberian counterparts.82

The sugar industry came to be a significant contributor to the British colonial economy, and it cultivated critical domestic industries. Extensive networks of finance and commerce emerged that advanced the nation’s economy.83 A dark undercurrent of this economic development was the creation of an infrastructure that facilitated slavery. Due to the intensive demands of sugarcane harvesting, colonial powers exploited indigenous peoples, and eventually African slaves, as a labor source.84 During the time period when slave labor was utilized to process sugar in the Americas, an estimated twelve million people were enslaved from Africa.85 Sugar and slavery became intricately intertwined and came to form the triangular trade model of mercantile economies. The widespread use of slave labor on sugar plantations is largely believed to have facilitated the introduction of slavery into the American South.86 The gruesome toll of slavery caused abolitionist groups to call for its end. When Britain abolished the slave trade to its colonies in 1807, sugar plantations began using a contract labor system.87 Continued cultivation of sugar, and technological innovations such as the introduction of white beets as an additional source of sugar, eventually led to its widespread availability.

Historical Uses of Sugar

The initial uses for sugar reflected its scarcity. Ancient civilizations in the Mesopotamian region used honey to create sweet treats. Scraps of parchment from 1400 BC contain a recipe for a dessert that rolled honey, dates, almonds, and sesame seeds.88 Arab apothecaries, and eventually their medieval counterparts, used sugar as a medicine to treat a variety of ailments. Sugar was also used to combine compounds, and it functioned as a sweetener to mask the bitter taste of medicines.89 Due to its status as an imported spice, sugar was attainable only by aristocrats and served as a symbolic representation of their wealth and power. Precursors to pies and cakes were served as desserts at extravagant banquets, and candied nuts and fruits were given as parting gifts to guests.90

As sugar gradually shifted from a luxury good to a commodity, increased availability led to new and innovative uses. When the Spanish expanded their colonial empire in the sixteenth century, they discovered the rich chocolate drink that was consumed by the Aztecs. By adding sugar and milk to the beverage, the Spanish sweetened the traditional base that was created by crushing cacao beans to a thick paste. Admiring the exquisite taste profile of this treat inspired by the New World, the Spanish royals shrouded it in secrecy for years.91 The expansion of the sugar trade, specifically by the British, led to an increased supply of sugar. A royal confectioner is credited with developing the first eggy custard that would serve as the base for ice cream.92 By the nineteenth century, the wide availability of sugar renders it a commodity. Home cooks begin to devise recipes for cupcakes and cookies that become the staples of any dessert repertoire.93 The Industrial Revolution, and advances in food chemistry technology, led to the eventual mass production of hard candies, chocolates, and prepared baked goods that line the shelves of contemporary markets.94

Health Implications of Sugar

Sugar is a ubiquitous part of modern life. Commonly found in beverages, desserts, and prepared foods, it’s a substance that is difficult to avoid. Sugar also features prominently in the lexicon of popular culture. Novels such as Charlie and the Chocolate Factory highlight sugar’s allure. Common terms of endearment often invoke or have associations with sugar. The wide availability of sugar combined with a cultural affinity for sweetness has led Americans to consume significant quantities of added sugar. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calculates that American males and females over the age of twenty consume 74 pounds and 50 pounds of sugar on an annual basis, respectively.95 American boys and girls between the ages of two and nineteen consume even more than their adult counterparts. The CDC pegs their annual consumption at 75 pounds and 59 pounds, respectively.96 To place these amounts in perspective, reports published by the USDA97 and the WHO98 suggest that calories derived from added sugars should not exceed 10 percent of daily caloric intake. Americans are surpassing these guidelines with recent estimates suggesting that people over the age of six have added sugar representing 14 percent of daily calories.99

Added sugar consumption has a variety of direct and indirect health implications. Sugar is known to produce tooth decay as specific kinds of bacteria use it as a food source. These bacteria produce acids that erode tooth enamel which leads to the development of cavities. The length of time that sugar is in contact with these bacteria matters. Sticky or hard candies prolong the exposure of teeth to sugar and provide the bacteria with a greater food supply.100 Consuming added sugar has also been linked to obesity as exceeding the body’s caloric needs will result in the creation of fat. It is obesity that then places individuals at greater risk for conditions such as cardiovascular disease and type II diabetes. The medical community has given specific attention to fructose consumption as it is metabolized primarily in the liver. When fructose is consumed in liquid form, such as in soda, the liver must work harder to metabolize the sugar. Studies have shown that when this fructose inundation occurs in laboratory rats, the fructose is converted to fat. This causes insulin resistance, the primary problem associated with obesity that links it to heart disease and type II diabetes. There is speculation that this phenomenon may also be a mechanism that causes cancer.101 Additional studies are probing for whether added sugar consumption directly increases an individual’s risk for the development of serious ailments. A study published in JAMA Internal Medicine shows that a diet where added sugar represents a higher percentage of daily calories increases mortality associated with cardiovascular disease.102 This multi-year investigation shows that people who received more than 20 percent of their daily calories from added sugar were twice as likely to die from cardiovascular disease as an individual that adhered to the USDA and WHO guidelines of added sugars contributing less than 10 percent of daily caloric intake.103 Further research and study by the scientific and medical communities will be needed to deepen society’s understanding of sugar’s role in human health.

Comments: