Teaching Strategies

Natural Selection

The concept of natural selection is based on the work of Charles Darwin. In 1859, Darwin wrote “Owing to this struggle for life, any variation, however slight and from whatever cause proceeding, if it be in any degree profitable to an individual of any species, in its infinitely complex relations to other organic beings and to external nature, will tend to the preservation of that individual, and will generally be inherited by its offspring. The offspring, also, will thus have a better chance of surviving, for, of the many individuals of any species which are periodically born, but a small number can survive. I have called this principle, by which each slight variation, if useful, is preserved, by the term of Natural Selection, in order to mark its relation to man's power of selection.”2 Phenotypes are observable characteristics and traits, including behaviors, which are variations within a species. Eye, hair or skin color, height, shoe size, etc.… are some examples of phenotypes within the human species. The patterns on a zebra, the shape of a bird’s beak, or the sound of a bird’s chirp are just a few examples of observable phenotypes, or physical variations, within animal species. Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection was based on the idea that these variations within a species could increase an individual’s ability to survive, compete for resources, and reproduce. More individuals with a favorable phenotype will survive to pass on their traits to future generations, while those with unfavorable traits will become the minority and may eventually be eliminated. Therefore, a species adapts to environmental conditions over time through the power of genetic variation, which is the raw fuel for the process of natural selection. Darwin observed different types of beaks among the finches of the Galapagos Islands. Since there were no other birds to compete with on the islands, the finches had adapted to niches in food availability. Some beaks were best suited for eating seeds and flowers at the top of a cactus, while other bird variants (in this example, species) had beaks favorable for foraging for insects at the base of the cactus.3

Another prime example of Darwin’s theory of natural selection can be found in the story of the peppered moths of England and Ireland. Peppered moths are predominately white with black speckles. This coloration provides excellent camouflage against bird predation when moths are resting on lichen covered rocks and trees. Some of the moths carry the gene for an almost solid black coloration, but their coloring makes them more visible to predators and their numbers at the time were scarce. In the 19th century, the air pollution from factories and coal burning in homes had a blackening, soot-covered consequence on the environment. During this era, the change in environment promoted a switch in the number of observable black moths. Now the black moths had a genetic advantage as they were better able to blend with their surroundings better than the speckled variety. As a result of their rapid generation times, within a short time period the black moths began to proliferate. “For example, the first black peppered moth was recorded in Manchester in 1848 and by 1895, 98% of peppered moths in the city were black.”4 In the mid-twentieth century, the impact of clean air legislation led to a cleaner environment. Once again, the tree trunks were whiter and growth of lightly-colored lichens increased. This was not favorable for the black moths, but the speckled moths began to flourish again. Both variations of moths still exist today, but the speckled moths are common and the black varieties are rare.

One of the lessons in this unit will include a simulation based on the peppered moth story. Once students have an elementary understanding of natural selection, they will be ready to learn about the closely related concept of artificial selection.

Artificial Selection

Artificial selection, often referred to as selective breeding, relies on similar processes that drive natural selection with one key difference – human intervention in the reproductive process to determine which variants (and hence, traits) dominate the population in future generations. Humans have manipulated biology this way for thousands of years without knowledge of genes or DNA or much of what we understand about biology today. In the introduction to their book on domestic evolution, author/researchers Driscoll and O’Brien write, “It was no more than 12,000 years ago that humankind began to consciously harness the 4-billion-year evolutionary patrimony of life on Earth. Exploiting the genetic diversity of living plants and animals for our own benefit gave humans a leading role in the evolutionary process for the first time.”5 Once humans started artificial selection to develop plants and animals for food, human population size soared from approximately 10 million people to the estimated 7 billion people living on Earth today, all in a span of about 12,000 years.6 The global impact has been profound. Today, 4.93 billion hectares are used for agricultural practices, which accounts for 70% of all fresh water consumed, and the world’s species are going extinct up to 10 times faster than the historic ‘‘background’’ rate, primarily contributed to habitat loss due to agriculture.7

Artificial selection can occur through a variety of methods. Direct gene editing using CRISPR technology is certainly a direct form of biological manipulation. Another form of artificial selection could be the culling of dandelions growing on a manicured grass lawn, with the goal of reducing the population of one plant species so that another may dominate. One of the first steps in farming is to clear the land, therefore reducing plant competition and modifying the soil to enable selected plants to grow. At some point around 12,000 years ago, humans began to increasingly rely less on hunting and gathering, and more on growing and sustaining food sources of their choice. Agricultural practices led to selecting the right plants to grow, and along the way humans discovered they could cultivate plants that grew and produced food better than other plant types. Trying to pinpoint the first domesticated plants is a challenging task, since agricultural practices developed over millennia in different locations. There is now convincing evidence for at least 10 such "centers of origin," including Africa, southern India, and even New Guinea.8 Wheat was an early plant to be cultivated and analysis of charred wheat spikelets from a 10,500-year-old archaeological site in Turkey helps tell a story. Upon microscopic examination, domesticated wheat bears a trademark scar from where the spikelet was torn from the stalk during harvesting. It may have needed human help to disperse its seeds. Wild wheat, also collected from the same region, does not have this scarring. Instead, the round and smooth spikelets could easily break free and disperse. The wheat spikelets with the scarring are viewed as evidence of the earliest known domesticated wheat in the world and are a physical sign of the rise of agriculture.9

Domestication

Domestication of a species, whether plant or animal, is a form of artificial selection. Dogs, cows, goats, sheep, and pigs are some of the earliest known domesticated animals, just as cereal grains such as wheat were some of the earliest domesticated plants. Animals that provided milk, such as cows and goats, were a valuable source of protein. Other animals were suited for labor intensive plowing, transportation, and as sources for wool, leather (hides), and fertilizer. As people began to raise these animals, they understood that allowing certain individual animals to breed could produce offspring that closely resembled the parents. They could use this knowledge to grow plants and animals with traits beneficial for feeding a growing human population. This population, beginning to thrive, relied less on hunting and gathering and could afford to settle in permanent locations. They would harvest the land for food and resources, and raise animals for food, service, and in some cases, companionship. This change in lifestyle also led to larger communities, where economics, intellect, art, and music would blossom, but would also be ravaged by warfare, famine, disease, and all the intricacies enveloping the human condition.

Domestication is at the heart of how humans arrived where we are today. It is a vast concept with implications that have rattled and elevated the course of human society’s trajectory; and yet as we marvel at the brilliance of human achievement we must not be blinded by the costs of such advancement. This was a resonant theme throughout my seminar work at Yale, and this unit serves to connect our forward thinking about CRISPR with a look at how we have handled the same moral questions in the past.

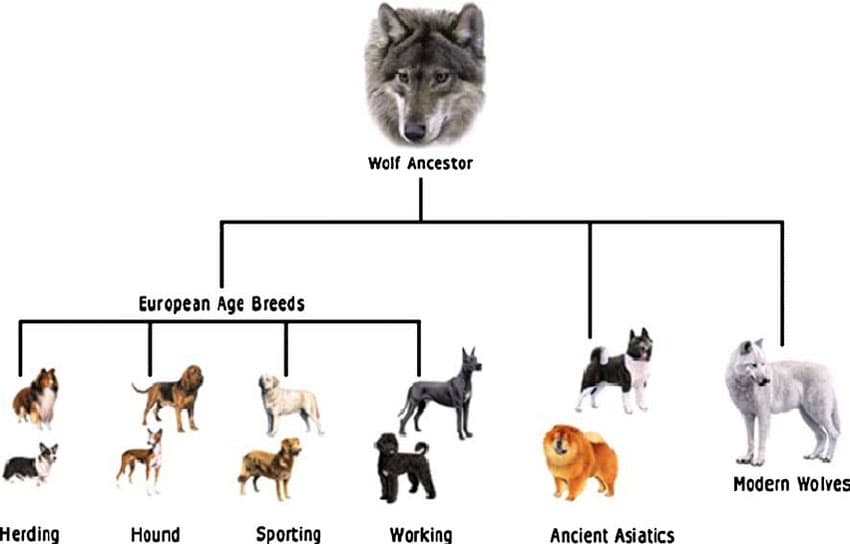

Domestication is the process by which a wild animal adapts to living with humans through selective breeding by humans over hundreds or thousands of years. Out of all the plants and all the animals that have been domesticated by humans, the dog currently outdates them all. Domesticated dog origins range from a known 14,200 years to an estimated 36,000 years ago. While the question of whether a dog was a dog before it was domesticated remains up for debate, we have been able to genetically show that modern dogs share a common ancestor of the modern grey wolf. The oldest record of a dog buried alongside humans was discovered in a basalt quarry in Bonn-Oberkassel, Germany. The incomplete remains of a dog, plus teeth of a second dog, were found at the beginning of World War I, along with the skeletons of a man and woman. Paleontology analysis shows that the dog appeared to not only have been buried with the humans at the same time, but was also cared for by humans. Carbon dating places the bones to be about 14,200 years old.10 Where the genetic divergence of dog and wolf took place remains controversial; it is further complicated by proposals that an initial wolf population split into East and West Eurasian groups and were domesticated independently into two distinct dog populations between 14,000 and 6,400 years ago. There is also fossil evidence from 35,000 years ago of a wolf from the Taimyr Peninsula in northern Siberia that diverged from the common ancestor of present-day wolves and dogs. The best knowledge that we have based on fossil evidence is that dogs, classified as Canis lupus familiaris and the grey wolf, Canis lupus shared a common ancestor, an ancient wolf species known as the Taimyr wolf. The grey wolf is currently the closest living relative to the dog. Dogs evolved from wolves through a centuries-long process of domestication and through this process, a dog’s behavior, life cycle and physiology have become permanently altered from that of a wolf, although they can breed and produce viable offspring.11

Figure 1 This basic family tree shows how wolves and dogs share a common ancestor. In one of the classroom activities, students will create a similar classification system based on their family tree.

In the 1950’s, two researchers in a brutally cold part of Siberia set out to conduct a groundbreaking experiment in domestication. In a span of less than 60 years, they could produce genetically and behaviorally domesticated foxes. Their story is fascinating, and is the subject of both a book and documentary which I will share in the resources section of this unit. This is how they did it:12

How to Build a Dog

First, select a species that is dog-like. Russian researchers Belyaev and Trut chose the silver fox. Dogs and foxes, while both from the larger Canidae family, cannot interbreed. They are too distantly-related genetically to interbreed, especially because these two species have different numbers of chromosomes.

Second, you need to collect a variety of individuals of that species suitable for breeding. Observe their behavior. Do some foxes seem a bit friendlier than others? Belyeav and Trut found that some variants of the foxes were more docile than others. They separated the most docile from the aggressive wild foxes.

Third, select a behavior trait you want to encourage and play matchmaker. In this case, you want them to be friendly and trusting of you, a human. Belyaev and Trut bred the docile foxes with other foxes, some also docile, some not. The fox pups were hand raised, and as they grew, some developed a docile trait and others became aggressive towards people.

Fourth, keep repeating step three. Foxes were sorted and bred again with other affectionate foxes, with an attempt to insure they still came from a variety of bloodlines. Over several generations, the selected trait of friendliness began to increase. Some individual foxes acted very much like dogs. They wagged their tails, licked the researchers’ faces, and behaved quite affectionately. Trut even invited one affectionate fox, Pushinka, to live in her home just like a domesticated dog. Seven generations later, while continuously breeding tame foxes, Belyaev and Trut noticed subtle changes in their foxes. Some of the offspring were retaining juvenile features, both physically and behaviorally, for a longer period. Belyaev realized that development was controlled by hormones, and their fox breeding was beginning to produce a hormonal variance. Belyaev was overjoyed at what he described as the beginning of genetic domestication.13 After 60 years, the research continues today. Belyaev died in 1985, but Trut still carries on the research program. Their foxes now show even further domesticated features, such as a shorter snout, curly tales, spotted fur, and barking at strangers yet relenting when humans welcome the visitors.14

Positive Traits, Negative Consequences

The third activity in this unit is a Design-a-Dog simulation based on the concept of selective breeding of dogs. While we have established that the first dogs genetically diverged from wolves thousands of years ago, that does not explain why we have so many different looking dogs today. Some are so small you can fit them in a shirt pocket, while others are so large that you could understandably confuse them with a small horse. They vary in color, body proportions, speed, smell, and temperament. They can be trained to assist us with rescue operations, to help the disabled, to keep us safe from danger, and to provide a loving and spiritual connection of companionship unrivaled by any of the over 6,495 species of mammals currently known to exist.15

One example of a dog bred for its special abilities is the bloodhound. It is one of the best tracking dogs due to the 230 million scent receptors in its nose. This is about the same as the grey wolf, but a human, for comparison, only has about 5 million scent receptors. In addition, the olfactory section of the brain that processes smell is about 40 times in comparative size to the same portion in a human brain. Simply put, this dog’s ability to track a scent is incredible. Per an article in Nature magazine, “When a bloodhound sniffs a scent article (a piece of clothing or item touched only by the subject), air rushes through its nasal cavity and chemical vapors — or odors — lodge in the mucus and bombard the dog’s scent receptors. Chemical signals are then sent to the olfactory bulb, the part of the brain that analyzes smells, and an ‘odor image’ is created. For the dog, this image is far more detailed than a photograph is for a human. Using the odor image as a reference, the bloodhound can locate a subject’s trail, which is made up of a chemical cocktail of scents including breath, sweat vapor, and skin rafts. Once the bloodhound identifies the trail, it will not divert its attention despite being assailed by a multitude of other odors. Only when the dog finds the source of the scent or reaches the end of the trail will it relent. So potent is the drive to track, bloodhounds have been known to stick to a trail for more than 130 miles.”16 Other features of the bloodhound also assist it in tracking a scent. Long ears help sweep up scent from the ground, and folds of skin on the face, neck, and chest help trap a scent. The dog is hardy and can tolerate traveling a long distance. These features were retained and enhanced through thousands of years of selective breeding, and the benefit to human society has been impacted. While these traits were probably developed for hunting, bloodhounds can also be used to track a criminal or find a missing person. They can be trained to detect harmful drugs or explosives. They can even be trained to smell low blood sugar or certain types of cancer in humans! Selective breeding has been the key method of developing this trait, and in this case many positive traits were enhanced. Unfortunately, there are many dogs that face a variety of debilitating and potentially lethal health problems that can also be attributed to selective breeding. Many of these problems lead to animal suffering and premature death rates. While the longer process of natural selection may have, over time, produced an animal with all the positive traits retained, the longer process also helps weed out some undesirable traits as well. For example, the German shepherd carries a gene making hip dysplasia, a malformation of the hip joint, a commonly inherited trait. This crippling and painful condition leaves the individual German shepherd prone to a life of hip joint pain and suffering. There are other genetic consequences of selective breeding. Pugs and bulldogs were bred to have a very short snout. As a result, they have a less powerful sense of smell, difficulty in warm weather due to limited panting abilities, and major respiratory problems throughout their lives. Some dog breeds are prone to back and skin problems, cancers, cataracts, and a variety of maladies that are prevalent in a certain breed. Whereas dogs with these problems may not exist today had they evolved naturally, it makes sense that if we want to give human intervention credit for developing positive traits, we have to take credit for the negative consequences as well. This would make an excellent ethical debate topic in a classroom discussion.

Comments: