The Rhetoric of the Writing

One way to help students get to Gallagher’s second and third questions is by helping them understand the rhetoric in the writing at the essay, paragraph, and sentence level.

In Rhetorical Grammar, Martha Kolln explains how students must understand “the grammatical choices available to them when they write and the rhetorical effects those choices will have on the reader.”

Perhaps the most useful section Kolln’s book is “Part II: Connecting with the Reader.” Here, the author addresses two elements that can help students address Gallagher’s second and third questions: Cohesion and The Writer’s Voice.

Kolln explains cohesion in terms of repetition or “lexical cohesion” (67). We might see a word, idea, image repeated in the essay. We might also see, Kolln explains, “synonyms and other related words, not just actual repetition: birds/robins, rodents/mice, evening meal/supper, friend/companion, vacation/trip/holiday” (68). Or this cohesion might arrive in the form of parallelism, “the repetition of whole structures, such as phrases and clauses.”

Ta-nehisi Coates brings forth the use of parallelism in the beginning of the essay’s high point where he decides what he wants his son to do:

“But still you must struggle. The Struggle is in your name, Samori—you were named for Samori Touré, who struggled against French colonizers for the right to his own black body. He died in captivity, but the profits of that struggle and others like it are ours, even when the object of our struggle, as is so often true, escapes our grasp.”

Coates continues in this section to reveal the wisdom and intellectual legacy his son must inherit:

“I have raised you to respect every human being as singular, and you must extend that same respect into the past. Slavery is not an indefinable mass of flesh. It is a particular, specific enslaved woman, whose mind is as active as your own, whose range of feeling is as vast as your own; who prefers the way the light falls in one particular spot in the woods, who enjoys fishing where the water eddies in a nearby stream, who loves her mother in her own complicated way, thinks her sister talks too loud, has a favorite cousin, a favorite season, who excels at dressmaking and knows, inside herself, that she is as intelligent and capable as anyone.”

Kolln reminds us to distinguish between repetition and redundancy. “Parallelism of the kind we see [in Coates’s essay]--parallelism as a stylistic device--invariably calls attention to itself” (83). The parallelism, in Kolln’s terms, “added a dramatic dimension to the prose” (83). Redundancy, on the other hand, is “the unwanted repetition of known information” (153). This approach should, again, emphasize the importance of an audience-centered writing experience for students. Parrallelism, I’ve explained to students over the years, should contribute to increased emphasis or development of an idea or situation that merits this extra attention.

As students draft their transformation section first--before they write the lead or end--they can ask themselves, “When did everything change?” Because this section of the personal essay should be the most intellectually or emotionally intense in all of the text, the use of parallelism contributes to the stylistically effective impact. Common types of parallelism fall into three categories:

Anaphora: the repetition of a word or phrase as used in Coates repetition of “who” in the example above

Antimetabole: repetition in inverted order as in the classic argument by many Mexicans living in the U.S. Southwest--”We didn’t cross the border; the border crossed us.”

Antithesis: the repetition of concepts using opposites as in Neil Armstrong’s “small step for man, but a giant leap for mankind”

Zinsser’s ideas about “unity” compliments Kolln’s ideas about cohesion. The author suggests writers ask themselves some questions such as, “In what capacity am I going to address the reader? (Reporter? Provider of information? Average man or woman?) What pronoun and tense am I going to use? What style? (Impersonal reportorial? Personal but formal? Personal and casual?) What attitude am I going to take toward the material? (Involved? Detached? Judgmental? Ironic? Amused?) How much do I want to cover? What one point do I want to make?” (51-52).

Accomplished teachers know the answers to these questions come from structured experiences of the pre-writing and writing processes. If these questions overwhelm the writer, Zinsser offers another piece of guidance: “Decide what corner of your subject you are going to bite off, and be content to cover it well and stop” (52).

A rhetorically effective length for personal essays written by high-school students has proven to be two-three typed double-spaced pages. Less than that, the essay runs the risk of coming off as underdeveloped. More than that and the writer risks losing the reader. If the piece will appear online, an effective length is 600-1,000 words, experience has taught me. Of course, the artful essays we read in class don’t have to be limited by these constraints. The mentor texts we select for students can—and perhaps, should be—longer to help them develop stamina as readers.

A highly effective, and longer, personal essay that demonstrates the cohesion (or unity) is “Under the Influence” by Scott Russell Sanders. This mentor text takes on the experience of being an alcoholic’s child. The author, now grown and accomplished, reflects on the damage on his family as a result of the alcoholism. While this could have been a predictable essay where the grown son tells about all the ugly moments, describes the father’s death, and then ends by reflecting on his relationship with alcohol, the unity will help students see how the essay escapes this trap of triteness. Interestingly, the predictable plot line I mention above is what essentially happens in the essay. However, Sanders’s use of rhetorically impressive cohesion and incorporation of other texts produces a richly crafted essay that reinforces Delacroix’s idea that “what has already been said is still not enough.”

First, the Norton Reader categorizes this essay as a profile, making it a resource that can push students to write about someone else’s experience through their lens. Ultimately, this profile reveals as much about the writer as it does about the alcoholic father. Any well-written personal essay should reveal as much about the writer as it does about the subject.

The essay builds off the the opening sentence: “My father drank” (36). To present the intensity of this situation, Sanders develops the cohesion by comparing his father to “a gut-punched boxer,” and “a starving dog.” The use of verbs here teaches students to challenge themselves in the revision process. Phrases such as “gasps for breath” and “gobbles food” extend the boxer and dog images, respectively, to communicate the severity. In what I call the background section (the part of the essay that contextualizes the conflict or explains how it started) Sanders creates cohesion by presenting “synonyms for drunk: tipsy, tight, pickled, soused, and plowed” (37). He develops the background with references to the Greek and Roman gods of wine and intoxication. He references the cultural acceptibility with drunkeness. His use of Roethke’s “My Papa’s Waltz” hints at the duality of living with an alcoholic: could be comfortable at times and could be frightening at times. The personal experiences become merged with Bibilical references and on and on the trauma gets exposed and connected to other sources that highlight the need for transformation.

The high point of the essay comes when the writer’s father, after fifteen years of sobriety, drinks again. Sanders recalls how he watched “the amber liquid pour down his throat, the alcohol steal into his blood, the key turn in his brain” (44). The connections Sanders makes to a process, a series of automatic cause and effects, contributes to the unity, the surprise, and the importance of this public point. The cohesion between this scene and the end is poignant as the writer grapples with his own addiction to work--which is exposed to him by his child.

In seminar, I shared how this essay could also lead students to a good conversation about audience. The intended audience is probably not alcoholics. It could be someone who drinks too much regularly or on occasion. But, I’ll argue, the public point to readers of “Under the Influcence” is to the children of alcoholics who must decide what they want the legacy of an alcoholic parent to be.

To help students analyze and evaluate the cohesion of an essay, they can use Zinsser’s questions to create a table such as this and continue filling in the chart with textual evidence.

Here is how they might fill in the chart using Coates’s essay:

|

A. What public point does the writer aim to make? Young African American men should never never forget how the legacy of racism destroys lives today, reminding us of young men of color’s obliteration when they consider themselves “white” or free of struggle. |

||

|

B. Logos (presenting ideas, evoking contemplation): In what capacity does the writer address the reader? (Reporter? Provider of information? Average man or woman?) What pronoun and tense does the writer use? |

C. Ethos (gaining the reader’s trust) What style does the writer use? (Impersonal reportorial? Personal but formal? Personal and casual?) [The metacognition] |

D. Pathos (evoking emotions in the reader): What attitude does the writer take toward the material? (Involved? Detached? Judgmental? Ironic? Amused?) |

|

The question is not whether Lincoln truly meant “government of the people” but what our country has, throughout its history, taken the political term people to actually mean. the elevation of the belief in being white was not achieved through wine tastings and ice-cream socials, but rather through the pillaging of life, liberty, labor, and land Eric Garner choked to death for selling cigarettes; because you know now that Renisha McBride was shot for seeking help, that John Crawford was shot down for browsing in a department store |

a popular news show asked me what it meant to lose my body I am accustomed to intelligent people asking about the condition of my body I felt an old and indistinct sadness well up in me |

Americans deify democracy in a way that allows for a dim awareness that they have The destroyers are merely men enforcing the whims of our country, correctly interpreting its heritage and legacy. all our phrasing—race relations, racial chasm, racial justice, racial profiling, white privilege, even white supremacy—serves to obscure that racism is a visceral experience |

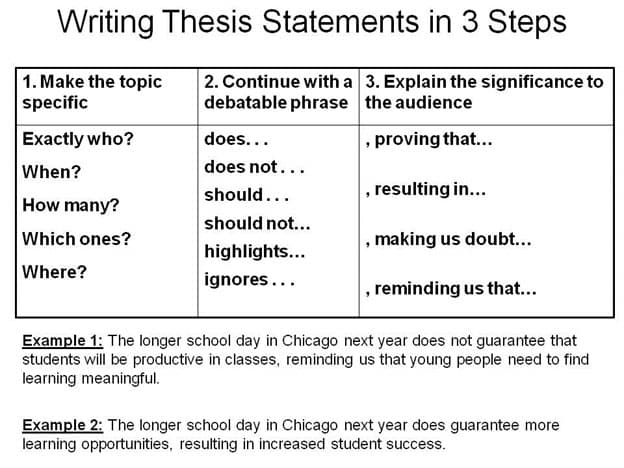

To help students through the classication, I added information about logos, ethos, and pathos. The public point can be expressed in many different way but should be presented as a debateable argument. It’s the writer’s argument, after all. Years ago, I developed the following structure to guide students through the development of an argument that avoids the rudimentary one usually taught, which includes three reasons. I say more about this in my essay “If You Write or Teach 5-Paragraph Essays, Stop It!” on my blog, The White Rhino, at ChicagoNow.com.

As students fill in parts of the chart with Zinsser’s questions (and these can be divided up among the class for a more efficient experience), they can begin to make sense of why this essay matters. We must recognize, of course, that there might be information that can go in more than one column. Students can make thoughtful classifications by looking at the pattern of information beginning to reveal itself in each column. They might ask themselves, “Does this information fit with the cohesion that’s being revealed or should it go somewhere else?”

This exercise serves mainly as a deconstruction exercise where students examine how the essay was put together. If students need a more hands-on approach to this, they can use index cards and a long piece of yarn. The writer’s argument goes at the top. One of the questions goes on another card underneath that. Individual pieces of evidence go on separate cards that are taped on the yarn in the order they appear in the essay. While an analysis of the entire essay would be possible, this would be overkill. Instead, students can closely examine a specific section of the essay. If we examine the structure of most effectively written essays, we’ll see five parts--not five paragraphs:

The lead with the conflict

Background on how this conflict began

The experience that extends the conflict

The turning point with the intellectually or emotionally charged experience where the situation changed

The insightful closing that echoes the lead without redundancy

To ensure students engage with the third question of “What does it matter?” as presented in Deeper Reading, students can draft a paragraph that evaluates to what level the writer revealed the intended public point, or argument, through the cohesion of one or more of the columns.

To guide students, with this writing exercise, we can turn to four paragraph structures presented in The Writer’s Options: Combining to Composing:

The Direct Paragraph: “opens with a direct statement of its topic sentence. The sentences after the opening develop the paragraph’s controlling idea by defining it, qualifying it, analyzing it, and--most frequently--illustrating it” (197).

The Climatic Paragraph: “a direct paragraph turned upside down: (198-199).

The Turnabout Paragraph: “move in one direction and then ‘turn about’ in another. The turnabout paragraph begins with an idea that is often the opposite of its controlling idea” (200).

The Interrogative Paragraph: “opens with a [thought-provoking] question” (202).

To help students judge their own and their peers’ cohesion in essay drafts, students can turn to some of the “Rhetorical Reminders” Kolln presents at the end of the chapter on cohesion when they examine each other’s drafts:

“Have [the writer] anticipated [the] reader’s expectations?”

“Do [the writer’s] paragraphs profit from lexical cohesion, the repetition of words?”

“[Has the writer] used metadiscourse effectively to signal the reader where necessary?”

“[Has the writer] taken advantage of parallelism as a cohesive device?”

“[Has the writer] used specific details to support [any] generalizations?”

Comments: