We Know Better but Will We Do Better?

According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, an assessment was taken from the 1970s that showed there was a 53 point gap in reading scores between black and white students 17 years of age. That gap was narrowed significantly in the following years and by 1988 was merely 20 points. At this time, almost every school district around the nation had implemented and were continuing to practice enforced integration to varying degrees. Although the Northeast continued to fight to remain in its previously segregated state within the classroom, the south was making gains once thought impossible. In the south in 1968, 78 percent of black children attended schools that were almost exclusively minority schools. By 1988, that number decreased to 24 percent. (42) These trends continued on the West Coast of America as 51 percent of black children attended schools that were almost exclusively black; the number dropped to 29 percent within a twenty-year window. (43) Yet as city populations have dwindled and school boards have seen integration as less of a priority, schools have become more segregated and those students unable to maneuver attending magnet schools or schools in the suburbs have suffered academically, according to test results.

Nikole Hannah-Jones, an investigative reporter with The New York Times, studied several schools systems throughout the United States. One system she focused on was Durham, North Carolina. In an interview on “This American Life,” Ms. Jones stated that “in 1971, blacks 13 years old tested 39 points worse than white kids. That dropped to just 18 point by 1988 at the height of desegregation. The improvement in math was close to that, though not quite as good.” (44) Ms. Jones explained that it was bigger than just putting white kids next to black kids. She states “what integration does is it gets black kids in the same facilities as white kids, therefore it gets them access to the same things those kids get.” (45) She claims that if “you’re surrounded by a bunch of kids who are all behind, you stay behind. But if you’re in a classroom that has some kids behind and some kids advance, the kids who are behind tend to catch up.” (46)

Jones explains that students who are in schools with concentrated poverty don’t have that option. There might be a few students, but most students with parents who have means and other options leave. Ms. Jones doesn’t hold back about her feelings toward the majority. “White people fled the school system, basically they resegregated school systems by fleeing.” (47) Jones is a product of busing herself. She grew up in Waterloo, Iowa. She and her sister, two of five black students, rode a school bus for two hours each day to go to school. Jones explains that there were some social issues with her leaving the community she knew to study in a community she had little connection with, but she is glad her parents made the decision. Jones says, “ I think I’m so obsessed with this because we have this thing that we know works, that the data shows works, that we know is best for kids. And we will not talk about it. And it’s not even on the table.” (48)

Two people I had the chance to interview for this piece were John and Jacquelyn Means, my parents. Jacquelyn, who grew up in Holt, Alabama, explained that she had integrated the Tuscaloosa Public Schools under The Freedom of Choice Program in 1968. The program allowed parents to integrate schools that were previously only for white students as long as they found their own way to school. The program was progressive as it came two years before the county integrated all of the schools in Tuscaloosa via federal mandate. Before this, Jacquelyn attended Botler High School. Her parents had served on the Civil Rights Council in the community and they saw this not only as an opportunity for their five children but all children of color. Jacquelyn explained, “ I remember coming home one day and my mom said that we would be changing schools in the fall. It wasn’t like we had a choice. I lived in an era when we did what we were told to do by our parents.” (49)

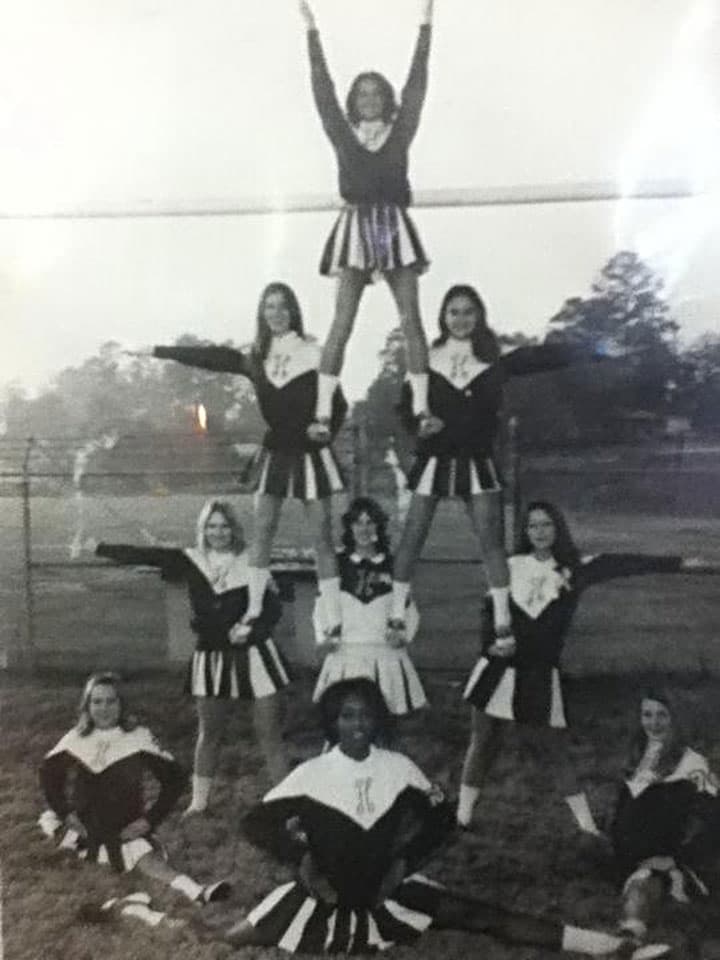

That fall, Ms. Means and four other students entered Holt High School, a 7-12 grade school in Alabama. Jacquelyn entered as a 9th grade student, along with her sister Estoria, Gwen Martin, Sanja Lee and another student she couldn’t recall. When asked about funding, she screamed, “Funding!! They had better equipment, libraries, books, everything!!” (50) She seemed giddy, reflecting on what she saw that fall much like a kid on Christmas morning. An active student Ms. Means explained, “they taught me golf, tennis and horseback riding,” activities that would later be taken away during the forced integration because they were considered to be elite. (51)

(Jacquelyn Means and teammates, Holt High School)

Ms. Means continued: “I had a new book in every class I took.” (52) She explained that they had to share books when she was at Bolter and many of those books were missing pages. She pondered for a moment and then spoke softly, “What’s strange is that Bolter and Holt were just over a mile and a half from each other.” She continued, “We went on field trips at Holt. I can never remember going on a field trip when I was at a black school.” (53) Many of her friends still went to Bolter that first year. Although Jacquelyn didn’t want to go Holt at first, she understood why her parents made the decision and she believed it has made her a better person today. “I had friends on both sides, Black and White. I think that is why I have been able to cross over the lines with my friendships today. The decision that my parents made put me in a better place to navigate the world.” (54)

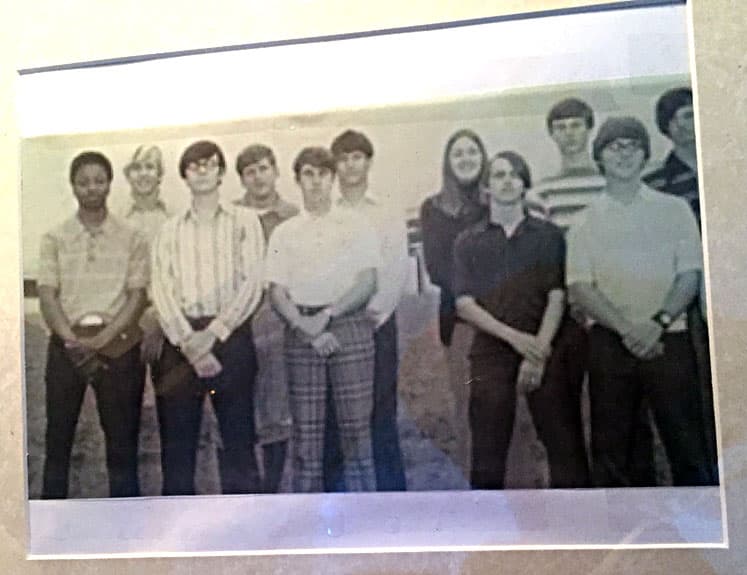

Unlike his wife, John Means Jr. had grown up to be a bit more rebellious. His neighborhood in Mobile, Alabama was harder and he didn’t make great grades. “I saw my first serious stabbing when I was 10. One teen stabbed the other teen above the heart and blood was squirting for what seemed like three feet. This stuff happened all the time,” Mr. Means said. (55) In order to get his son a better life, John Means Sr. had his son integrate schools at the first possible chance. John Means Jr. left his all black school called Leona B. Warren Elementary (1st-6th grade) and made his way to Azalea Middle School and Davidson High School. When he first started, the school had 3,800 students, 800 in the graduating class and only 14 African Americans, including himself. Like his wife, John was surprised by the amount of funding the school had, explaining “it was like night and day.” In addition to having better facilities, he said, “they had fancy cars in the parking lot from country club kids, nice clothes for the students and teachers.” (56) He continues, “I had way different classes: Advanced Physics, Chemistry and Latin. The school had a key club and beta club. They had everything to drive achievement. I thought I had gone to hang with the rich people,” he said with a chuckle. (57)

(John Means, golf team, senior year)

In addition to the better classes and facilities, John was extremely happy to find out that his new school had a golf team. Although it took him three attempts to make the team, he finally did and that was “his ticket,” as he called it, to a scholarship to Tuskegee University and playing competitive golf. He said this would have never happened if he hadn’t integrated the school. It was at Davidson High School that he found his love for mathematics and engineering. Davidson offered higher level math courses than the schools he would have gone to just a few years before and the labs he had access too were far better than anything his previous school could have provided. However, he did believe that the teachers at his old school “were good teachers. They cared about us and our success, they just didn’t have the same resources as Davidson.” (58)

I appreciate that these two individuals took time out of their busy schedules to tell me about their time integrating the schools in Alabama. They both were living during George Wallace’s tenure as Governor and there were more than enough roadblocks to stop what they were trying to accomplish. Separate but Equal was never intended to be equal and that remains the case today. Today, schools that have been failing for years are a stone’s throw from other schools that have been a pillar of success within their communities. While there are many people who will act as if these differences happened as a matter of fact or dumb luck, we know better. So we must take steps to do better.

Comments: