Content Objectives

Imagine an advertisement that states: “Today fresh bananas that took one million years to make are only $0.29 a pound!” When considering the origins of photons from the Sun that are captured by plants to make sugar and release the vital byproduct of O2, this headline is fact, not exaggerated fiction. This unit for high school biology of any level explores photons and photosynthesis.

Entering my 16th year of teaching biology, I have found the least amount of time to teach specific concepts that stray from core curricular concepts. I teach in the city of Philadelphia at the Philadelphia High School for Girls. With Pennsylvania state and Philadelphia city standardized tests driving much of the biology pacing, there is not a lot of room for curricular creativity in a required subject like biology. As a magnet all-girls public school, the Philadelphia High School for Girls attracts girls from throughout the sixth largest city in the United States who are academically driven and passionate learners. The rigorous course work, including a requirement for four years of science, demonstrates to the students that science is important. In ninth grade they take biology, which is connected to Philadelphia Benchmark testing given four times a year and a Pennsylvania Keystone test they are required to pass in biology to graduate. Because of the pressures to teach to very specific concepts on these exams, time for anything beyond the standard curriculum is at a premium.

My students certainly deserve a deeper dive into the inner workings of biological energy production like photosynthesis than what is generally afforded based on the curriculum and testing requirements. In addition to this, Earth and space science is not offered at all in high school. It is lightly glossed over in Environmental Science, but its absence is a glaring hole in their schooling. With this, they lack fundamental knowledge of the Sun. With its vital connection to life as we know it, photosynthesis and the sunlight necessary for it can be a catalyst for another rarely taught attention-grabbing topic: life on other planets. This curriculum unit, The Sun and Photosynthesis: From Photons to Astrobiology, unites these concepts.

Photosynthesis is one of the key metabolic concepts taught in high school biology. As a chemical reaction and one of the few entry points into plants that most students receive in grades 9–12, it is both intuitive and abstract. The majority of students understand what is needed to make sugar: CO2, H2O and sunlight. And while there is a general comprehension of where the two chemical compounds commonly come from – the breathing of other organisms and precipitation – sunlight is the easiest to know. The Sun is in the sky, raining sunbeams down on us and the rest of Earth. Plants absorb this sunlight to help power photosynthesis. But to know something deeper about the origin of every photon of sunlight is outside of the boundaries of biology, whether it be the version every student gets or a higher-level AP or IB course.

This curricular unit will pull back the curtain on the production of photons by our local star and reception of photons by plants while also looking at the possibility for life elsewhere in the universe using the photon journey and photosynthesis as a guide to life possibilities. In the first part of the unit the origin of photons in the core of the sun and their journey to the earth will be revealed in lectures, student research and labs. The second part of the unit will engage students in researching and presenting how interruptions or dilution of sunlight reception by plants via occurrences on Earth can affect photosynthetic output. The final section of the unit will turn students into fledgling astrobiologists who investigate possibilities for life throughout the galaxy and share their findings with the class.

The following are the overarching individual objectives for each piece of the unit’s main content.

- Students will understand how a photon journeys from the Sun to a vital part of producing sugar and O2 in photosynthesis.

- Students will understand how disasters can impact the atmosphere and consequentially the ability for photons to reach plants so photosynthesis can occur.

- Students will understand how astrobiology can identify potential habitable planets where photons from the nearest star could participate in photosynthesis.

Photon Journey and Photosynthesis

In order to understand the place of a photon in the process of photosynthesis, there needs to be an understanding of where the photon comes from, how long it takes to get out of the Sun, how long it takes to get here, how it enters photosynthesis and how it is used in photosynthesis. The story begins in the Sun’s core. A middle-aged yellow dwarf star that is around 4.5 billion years old, the Sun has a core that can reach a temperature of around 15 million degrees Celsius. The Sun generates about 4 x 1026 watts of energy through thermonuclear fusion. This fusion combines four hydrogen nuclei into one helium nucleus through the proton-proton chain. As a result of this, a gamma ray photon is emitted. And it is this photon’s journey we are going to focus on.

There are many hurdles for this photon on its journey. To begin with, the Sun’s core is dense at 150 g/cm3. The other layers of the Sun cause compression due to gravity, leading to the immense heat and density in the core. The core is so packed with the hydrogen, which provides the protons necessary for thermonuclear fusion and helium that is produced in the reactions, that an emitted gamma ray can only travel a tenth of a millimeter to a centimeter in the core before being absorbed and re-radiated by another atom. These short distances do not generally follow a straight path either. When a photon is re-radiated by an atom, it has the potential to go in any direction. This is called the “drunkard’s walk.” If there are normally 10 movements to get from point A to point B, it would take 102 or 100 movements to get from A to B because of the randomness of movement.

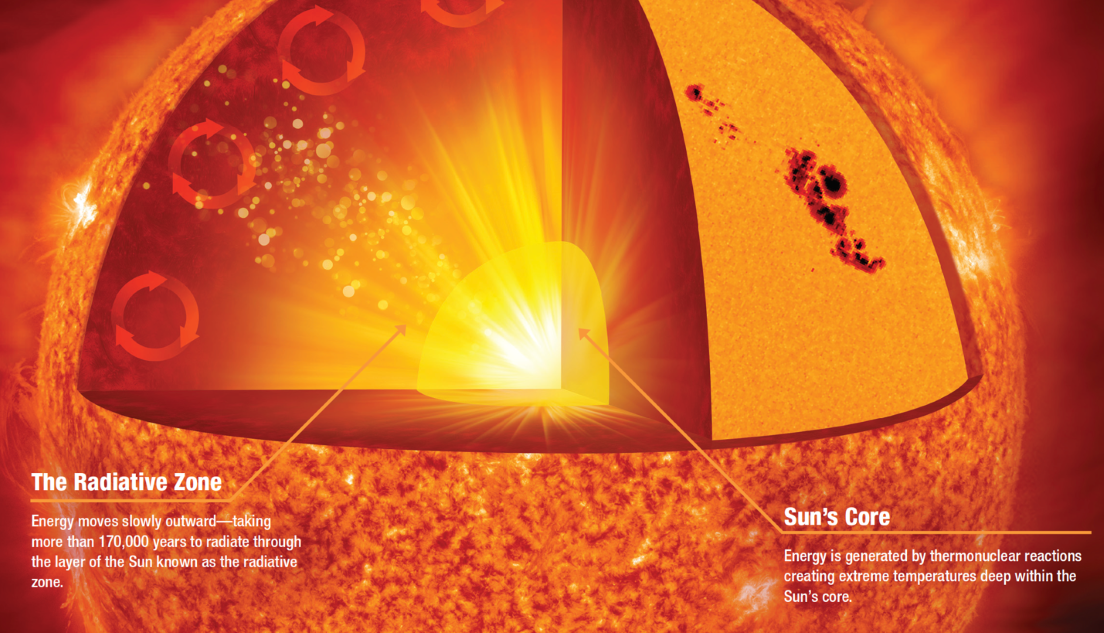

Thousands upon thousands of years pass before the gamma ray photon reaches the radiative zone of the Sun (see Figure 1). This zone extends to 496,000 km from the center of the Sun and is cooler than the core at 7 million degrees Celsius. Energy travels by radiation in this zone, with the photon being radiated at longer wavelengths after each absorption and re-radiation. The photon then enters the convective zone where energy is carried by moving matter through convection. The photon heats the gas in this zone, which is around 2 million degrees Celsius. Even with this heat it is not hot enough to re-radiate energy from the photon. Instead, the heated gases in the convective zone rise, carrying the photon with it. As the photon moves with these processes through the Sun, the photon loses energy at each step of the process.

Figure 1 Shown here are a photon's first two points on its journey, the core and the radiative zone.1

The last step in the Sun’s structure for photons is the photosphere. To get here from the core of the Sun takes between thousands and millions of years, depending on how the drunkard’s walk goes. In the photosphere, which is much cooler at 5800 degrees Celsius, granules and supergranules cover the surface. They are like giant cells that carry hot gas in many directions: towards the surface, sideways, and back down. Within the supergranules are smaller granules, millions of which cover the Sun’s surface. The granules are like hot bubbling gas cells that last 8-10 minutes. In this time, photons are radiated into space.

The Sun is 94.5 million miles from Earth. A photon that originated in the core of the Sun has taken between a few thousand years to millions of year to reach this point of traveling to Earth. Photons travel at the speed of light and they are passing through the vacuum of space to get from the Sun to Earth. Currently lacking any information about what kind of photon it was because of becoming thermalized, this photon, which was birthed so long ago, takes 8 minutes and 20 seconds to reach Earth.

When a photon enters the Earth’s atmosphere, its wavelengths could be in the infrared, ultraviolet, or visible light range of the electromagnetic spectrum (see Figure 2). Just as humans see the visible light spectrum, which is between wavelengths of 380 nm and 700 nm, plants also rely on this part of the spectrum for photosynthesis. When a photon comes into contact with a plant, it passes through the outermost layer of a plant leaf, the epidermis. Below the epidermis is the mesophyll layer of a leaf. Here the palisade parenchyma is found, which is the leaf layer with cells that have chloroplasts, the structures responsible for photosynthesis. The photon passes into the chloroplast and interacts with one of the chloroplast’s pigments. The two major chlorophyll pigments are chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b. Chlorophyll a absorbs blue and red visible wavelengths the most, while chlorophyll b absorbs blue and red-orange the most. There are also accessory pigments, the carotenoids, which absorb blue-green the most.

Figure 2 Shown here are the wavelengths of light among the electromagnetic spectrum.2

When this single photon strikes chlorophyll, an electron in the chlorophyll is excited, beginning the first stage of photosynthesis, the light-dependent reactions. This occurs in photosystem II, a multiprotein complex in one part of a chloroplast membrane known as the thylakoid membrane. When the excited electron leaves, a molecule of water splits, releasing an electron back to the chlorophyll, resulting in oxygen and hydrogen ion formation. The electron originally released by the chlorophyll in photosystem II travels through an electron transport chain in the thylakoid membrane until it is accepted by a chlorophyll in another multiprotein complex known as photosystem I. The energy lost from this electron helps to pump hydrogen ions into the interior of the thylakoid of the chloroplast. When in photosystem I, the electron is reenergized by the absorption of another photon. As a result of this absorption of another photon, an electron is sent to enzyme cofactor NADP+ to form its reduced form, NADPH, which will be useful in the Calvin cycle of photosynthesis. As a byproduct of the movement of these electrons from multiple photons, the hydrogen ions form a concentration gradient inside a thylakoid of a chloroplast and pass through the ATP synthase in the thylakoid membrane to aid in the catalyzation of ATP. The NADPH and ATP move onto the Calvin cycle. In order to get a single molecule byproduct of O2, eight photons are needed in the light-dependent reactions.

CO2 enters the equation in the Calvin cycle of photosynthesis. In order to fulfill the entirety of the photosynthesis equation, Light + 6CO2 + H2O → C6H12O6 + 6O2, six CO2 molecules need to go through the Calvin cycle. In order to make the C6H12O6 with the six CO2 and six O2 molecules, a minimum of 48 photons need to be absorbed in the light-dependent reactions. 48 different photons, that have already existed for thousands to millions of years will be used to make one molecule of sugar needed by plant for energy in aerobic cell respiration and needed by other organisms that require the sugar when eating the plant itself.

Photon Journey and Photosynthesis Objectives:

- Students will understand how photons are produced in the Sun and how they get to the Earth.

- Students will understand how photons are vital to photosynthesis reactions and the resulting products.

Interference with Photosynthesis

If something impedes the reception of photons, photosynthesis can be impacted. 66 million years ago an asteroid struck Earth in what is now the Yucatán Peninsula, creating the Chicxulub crater. This led to the extinction of more than 75% of Earth’s species at the boundary of the geologic Cretaceous and Paleogene periods. The asteroid impact created the 150 km Chicxulub crater, which lacked sulfur that should have been in the rock. Abundant in surrounding rocks, upwards of 325 gigatons of sulfur instead was released into the atmosphere. The sulfur would have created a haze that blocked photons from reaching Earth. The impact of the asteroid created shockwaves generating upwards of magnitude 9 earthquakes across Earth. Such shockwaves would have led to volcanic eruptions around the planet, ejecting particles that would have blocked photons. These particles in the atmosphere might have lasted a decade or longer. In addition, asteroid impact ejecta, which is material forced out due to an asteroid impact, superheated the atmosphere. This heat radiated to the ground, possibly raising surface temperatures 100s of degrees, causing wildfires to occur throughout the planet. Such fires would have caused soot to reach the atmosphere, further blocking photons. The immediate collapse of photosynthesis is met with a longer term positive. The rock in the ground where the asteroid hit was also rich in carbonate. The impact sent carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Most certainly causing global warming in the immediate aftermath of the impact, carbon dioxide would have lingered in the atmosphere potentially long enough to be used by plants when photons more regularly reached the surface, leading to greater ability for photosynthesis after the massive die-offs and extinctions. So, there were positives mixed in with all the negatives for photosynthesis found in this devastating event.

On April 5, 1815, the volcano Mount Tambora located in Indonesia became active. The volcano exploded over the following four months. This largest and most destructive of volcanic explosions in recorded history, the Mount Tambora eruption released around 150 cubic km of ash, pumice, other rocks and aerosols, including 60 megatons of sulfur, into the atmosphere. All of these substances prevented great amounts of photons from reaching the planet’s surface and reduced average temperatures by up to 3 degrees Celsius. All of this led to weather catastrophe a year later in 1816, the “year without a summer.” Frost events killed crops during the summer in North America and Europe. This occurrence shows how volcanic eruptions can have lasting impacts in other parts of the world when there is a reduction of photons being collected by plants for photosynthesis.

Not all volcanic eruptions lead to the same photosynthetic catastrophes. Much was studied after Mount Pinatubo erupted in the Philippines in 1991. Solar radiation decreased by around five percent, while direct radiation decreased by as much as 30%. With these changes, plants still could photosynthesize. Constant direct sunlight can lead to chloroplasts being saturated by photons, leveling off photosynthesis. Diffuse photon levels can actually be better in the long run. More carbon (up to two times as much) can be absorbed by the atmosphere in diffuse light, leading to an overall positive outcome in volcanic eruption occurrences.

When nuclear radiation or nuclear bombs affect an ecosystem, the damage to photosynthesis is only partially understood. Studies of plant life in Chernobyl post 1986 meltdown and the 1999 NATO bombing of Serbia with depleted uranium, some possible effects have been revealed. Photosynthetic pigment production is inhibited, which would limit the absorption of photons. Close to the epicenter of the meltdown or bombing there was high mortality of plants, stopping photosynthesis altogether. And as for nuclear bomb detonation, other than over the short term when the bomb exploded, there is no clear evidence of any long-term effects on photons getting through the atmosphere to plants below.

With wildfires in the news every year, they on their own should also be considered in how they affect photon absorption by plants. Consider the Australian wildfires that lasted from June 2019 until March 2020. Sunlight and, consequentially, photons had a reduced ability to reach Earth’s surface through the smoke of the fires. Satellite data showed that smoke aerosols formed a smoke cloud three-times larger than anything previously recorded globally, blocking sunlight from reaching the Earth. This led to a decrease in temperature of cloud-free areas of seas in the Southern Hemisphere by 1 Watt per square meter. There is a future upshot for photosynthesis after the wildfires. Plants will reappear in fire scorched areas through ecological succession and thus have access to increased CO2 in the atmosphere from the fires, leading to increased rates of photosynthesis. This shows how these disasters are nuanced in their effects on sunlight reaching Earth and the subsequent photosynthesis processing by plants.

Interference with Photosynthesis Objectives:

- Students will understand how natural disasters like asteroid impacts, volcanic activity and fires can impact photon delivery to photosynthetic organisms.

- Students will understand how man-made disasters like nuclear weapon explosions or nuclear reactor meltdowns can impact photon delivery to photosynthetic organisms.

Astrobiology and Photosynthesis

Astrobiology studies how life in the universe originated, evolved and is distributed. It does this by first looking at how life works on planet Earth. Astrobiologists then apply what is know about the characteristics of life to other places in the universe to predict where life could exist. The understanding of life begins with a baseline of requirements: having cells, genetic material, the ability to reproduce, the ability to evolve, the ability to respond to the environment, homeostasis or a stable internal environment, the ability to grow develop and metabolism. Metabolism is where photosynthesis and photons come into the picture, as the processing of energy through photosynthesis is vital to the vast majority of organisms’ survival. And then there is water, which is a substrate necessary for all life.

Water is thought to be used to show life can exist on a planet. And the thinking had been that water can only be found on planets in habitable zones or Goldilocks zones around a star. This is determined by a planet’s proximity to a star. If the planet is too close water could not exist because it would be too heated, while if it is too far away it would be solid ice and never allow for life. Being just the right distance lines up with the concept of Goldilocks. Just having water is not enough to say life exists, though, as Jupiter’s moon Europa, shows. It does have water. But there is no proof of life we have found. Water has been found in lakes hidden under Mars’ surface, but there is no proof that there is life. As we look to the rest of the universe, water is part of what is necessary for life.

Another way to tell if a planet is potentially habitable with photosynthetic life is to look for O2. This is a key biosignature, or chemical signature of life, because it is usually produced by photosynthetic life, can be found in detectable levels in the atmosphere, and has a spectral signature wavelength that astronomical instruments can detect. O2 has wavelengths detectable from ultraviolet to infrared from itself, O3 or O4. O2 is also mixed throughout different layers of the atmosphere, making it more readily found by astronomical instrumentation. The detection of O2 is not fool proof for finding life, though. It can be produced abiotically when H2O is photolyzed outside of photosynthesis via interaction with photons. O2 and its close relatives have been found in atmospheres in the solar system. Mars and Venus have small amounts of O3 from photolytic reactions with CO2 while Neptune can accumulate O2 because of its distance from the sun and not being in the habitable zone.

Looking for H2O and O2 is not a surefire way to determine if a planet is habitable, but it is a start. Looking for the light spectrum of water in different climate states will make this data even more helpful in discovering alien life. Cold, warm and the very warm “runaway Greenhouse” climate, which can cause oceans to evaporate and lost to space, all have different amounts of H2O vapor in their atmospheres. So, by looking at spectra from planets that can be detected, the type of atmosphere present can be determined. The challenge is being able to examine planets near to certain stars. M and K stars are fainter than the Sun (a G2 star), but they are more common and hence people are fixated on planets near them. The temperatures of these stars are much cooler than the Sun, with the effective temperature of M stars being 2,300-3,900 degrees C and K stars being 3,900 to 5,200 degrees C versus the Sun’s effective temperature of 5,780 degrees C. So the habitable zones will be closer to the stars, allowing for the possibility for life. With the cooler temperatures, different wavelengths will be emitted, with more emissions in the larger wavelengths. So photosynthesis as is known now would have to differ on possible life-bearing planets or not occur at all. On the other hand, there are greater dangers of increased UV and Xray bombardment, which would inhibit life as we know it (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Star types M, K, and G are compared here in habitable zone size, x-ray irradiance, relative abundance, and longevity.3

Let us consider some potential habitable exoplanets. Kepler-186f is about 500 light-years from Earth in the Kepler-186 system, which resides in the constellation Cygnus. The star it orbits is an M dwarf, which is cooler than the Sun and is about half the size and mass of the Sun. Kepler-186f is Earth-sized, most likely rocky and is in the habitable zone, so it has the ability to have liquid water that pools on the surface. Kepler-452b is also a candidate for a life-supporting planet. Sixty percent larger in diameter than Earth and only five percent further from its parent star, Kepler-452b is tantalizing in its potential to harbor life. Another potential life-providing planet is TRAPPIST-1d. It is Earth-sized, rocky and in the habitable zone. Only around 40 light-years from Earth, it orbits a red dwarf. There is a good change it has liquid water as well. Both Kepler-186f and TRAPPIST-1d are good candidates for carrying life and therefore having photosynthesis.

Of course, we know of life only on Earth. But what if there is another way to do photosynthesis that could evolve on a different planet? One consideration of binary and multiple-star systems. These systems are dominated by M and G stars. One of the issues becomes how would organisms, if they existed, evolve to adapt to different types of wavelengths coming from the two stars. One star would be closer and one further away. It is hypothesized that infrared and ultraviolet wavelengths could be emanating from the stars. Cyanobacteria can use infrared light to perform photosynthesis. And despite damaging internal photosynthetic machinery like photosystem II, ultraviolet light could also be beneficial for some forms of photosynthesis in the short term. Using these possibilities for binary and multiple star photon production, the potential for photosynthetic life to thrive elsewhere has increased greatly.

Astrobiology and Photosynthesis Objectives:

- Students will understand astrobiology and its applications.

- Students will understand how to use data about distant planets and their accompanying stars to determine if the planet could be habitable or not.

Comments: