Content Objectives: Biodiversity and its Origins

In the first week of ninth grade environmental science, I ask students to come up with as many things that are part of “the environment” as they can think and write in ninety seconds. Although most lists include some mention of the physical environment, for example, water, rocks, and the sun, the focus tends towards naming different plants and animals. Even without a formal definition, most people have an intuitive understanding of Earth’s biodiversity. Penguins are different from pandas. A house mouse is different from a potato, and springtime flowers show up in an expressive poetry of shape and color.

The living and nonliving things students write about tend to be easy to see and experience at the level of human senses. However, there are vitally important parts of the environment that are smaller than what humans can see with the naked eye. Bacteria outnumber all plants and animals by an order of several magnitudes,1 and viruses are “among the most abundant biological particles on earth.”2 Despite their near-ubiquity in Earth’s environments, bacteria and viruses have not yet made an appearance on a student list.

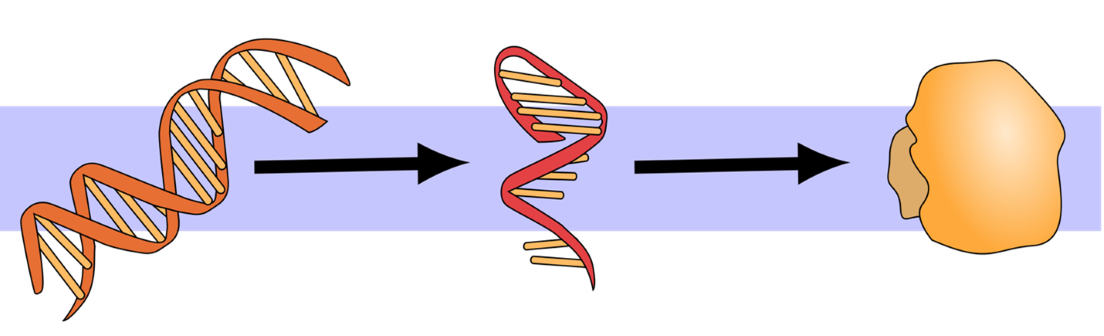

An even smaller feature of environmental biodiversity is that it can help us understand variety at the genetic level. Every living thing on Earth has its own unique genetic code found in the molecules that make up its deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA.3 Humans might count as one species with many traits in common, but we exhibit a great deal of obvious and not-so-obvious diversity in our genetic heritage. The connection between DNA and biodiversity is the “central dogma” of biology. DNA is transmitted from a parent to its offspring. When required by the daily activities of life or changes in the environment, segments of this DNA, called genes, can be copied, or transcribed, into RNA which a cell then “translates” into proteins to produce observable traits, called phenotypes (Figure 1).4 Although there are a number of exceptions to this unidirectional flow of information,5 it is a helpful starting point for ninth grade environmental scientists. Whether plants, animals, or microbiota smaller than human perception, all living things on Earth attribute their unique differences to genetic variation.

Figure 1. The central dogma of biology is that DNA is copied to RNA is translated to proteins6

Human Influence on Global Biodiversity

Although the technology to read and catalog these genetic sequences only developed in the latter half of the 20th century,7 humans have been influencing genetic diversity on Earth for tens of thousands of years.8 These practices include many hugely important examples, from agriculture to our favorite house pets, but a critical subset of organisms that humans have changed include those that have developed genetic resistance against human attempts to eradicate them.

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) top ten global health issues for 2021 included cancer, insect-borne tropical diseases like malaria, and drug resistant infections.9 While these might seem like a disparate collection of threats to human health and wellness, they all have one thing in common: certain members of their population are no longer vulnerable to medication or pesticides that were once effective.10 As summarized by the American Academy for Microbiology,11

Given time and opportunity, the organisms we seek to control will evolve resistance to agents deployed against them.

Recalling the diversity of individual humans, all populations will contain some amount of genetic diversity through random mutation to their DNA.12 In organisms that reproduce by having sex, additional genetic diversity is introduced by combining parental chromosomes during fertilization.13 That resulting offspring will further mix the chromosomes from its parents while making egg or sperm, recombining those genes for the next generation.14

The result is that sex and mutations can create many different versions of the same gene. Scientists refer to each of these unique versions as an allele. Two plants might have the same “gene” that controls flower color, but one has an allele that makes a purple pigment while another has an allele that codes for the color white. Different alleles can provide different advantages depending on their environment. For example, in a population of bacteria, a small number of alleles may have randomly evolved such that they confer resistance to a particular antibiotic. When humans then apply that drug in an attempt to treat a bacterial infection, individual bacteria with an allele for resistance will survive the antibiotic while their community members with the non-resistant, “wild-type” allele succumb to human intervention.15

Omitting words for clarity, this is “natural selection,” a fundamental mechanism for evolution as described in Charles Darwin’s Origin of Life,16

“...any variation… if it be in any degree profitable to an individual of any species, …will tend to the preservation of that individual, and will generally be inherited by its offspring. The offspring, also, will thus have a better chance of surviving…”.

Although the existence of the mutation was random, the bacteria with the resistance allele were “selected” by environmental pressures as better able to survive and reproduce, aka more “fit,” than their peers with the wild-type allele. Offspring from the survivors will also carry that pre-existing genetic adaptation and become more common in the face of on-going selection pressure. Over time, this can lead to very big changes in the genetic code and observable traits of a population, sometimes so different as to no longer be considered the same species.

Although high-school students are expected to be familiar with this idea that offspring will be similar to their parents because of heritable genetic material, bacteria and viruses have an additional complication in which genetic information can be exchanged between organisms of the same generation, called horizontal gene transfer.17 This can lead previously vulnerable populations to gain genetic resistance even without the presence of the selective pressure.18 There are many molecular mechanisms by which these organisms “outwit” chemical annihilation19 and the study of how resistance develops and spreads is an on-going field of research.20

Antimicrobials: A Case Study in Resistance

Unfortunately for humans, the story of bacteria that do not respond to chemical antibiotics is an increasingly familiar one. Initially discovered by Alexander Fleming in 1928, the ability of Penicillium mold to combat bacterial growth led to a post-World War II “golden age” of pharmaceutical antibiotics that could reliably manage bacterial infection.21 In 1936, nearly 120,000 Americans died from all forms of pneumonia.22 By 1956, that number had declined to just over 40,000,23 cutting the U.S. mortality rate from pneumonia to nearly one-third of the pre-antibiotic level. In 2005, data from the Centers for Disease Control suggested that 200,000 American lives were saved each year due to antibiotic interventions.24

However, pharmaceutical antimicrobials are losing efficacy. Bacteria are living systems that reproduce and mutate rapidly. When these chemicals are used against a population that numbers in the billions, a treatment with a 99.999% mortality rate still leaves several thousand survivors. When those survivors contain a trait for antibiotic resistance, that leaves them and their offspring no longer susceptible to the next application of that drug. There are even alleles that provide the ability to survive several different antibiotics, “broad spectrum resistance,” in one swift evolutionary step.25

This increasing prevalence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a top ten global health threat with grave social and economic consequences for the 21st century. High rates of antimicrobial resistance have been observed in all WHO surveillance regions26 and, in 2019, The Lancet reported that 900,000 to 1.71 million global deaths in the previous year could be attributed to AMR with a 95% confidence interval.27 In the United States alone, more than 2 million people are sickened each year as a result of antibiotic-resistant infections, resulting in at least 23,000 deaths per year.28 In 2010, seventy percent of hospital infections had resistance to at least one first-line antibiotic,29 and there are even microbes that have developed resistance to “all or nearly all” available antibiotics. Called Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae because they are resistant to carbapenem, the “treatment of last resort,” it is estimated that strains of Klebsiella and E. coli that have developed this resistance were responsible for 9,300 infections and 600 deaths in the U.S. in 2013.30 In human terms, these statistics are a daily reality for thousands of parents grieving the death of their child. It means young people losing the love and stability of one or both parents. It means millions of work hours lost to illness and recovery, thousands of missed school days because “the medicine doesn’t work anymore.”

Biomimicry: A Tale of Two Treatments

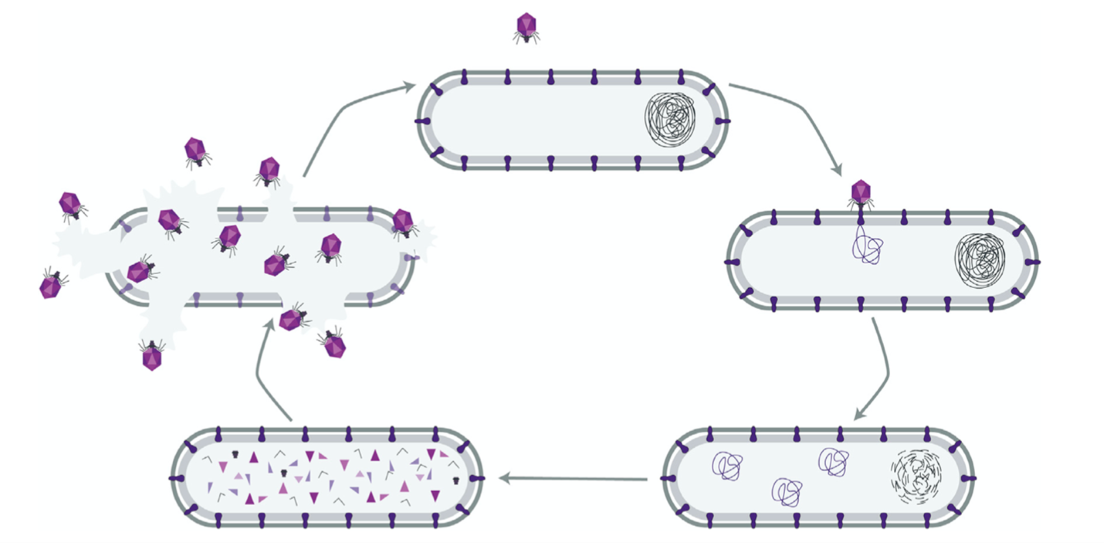

While the Western model of pharmaceutical antibiotics developed from Alexander Fleming’s observation of Penicillium mold, an additional “bioinspired” means of killing bacteria was adopted elsewhere. In 1915, British scientist Frederick Twort observed antibacterial properties in a “transparent material” that he hypothesized were ultra-microscopic viruses.31 That this transparent material was indeed full of bacteria-killing viruses was confirmed by French microbiologist Félix d’Hérelle in 1917.32 Called bacteriophages for “bacteria-eaters,” these “phages” infect a bacterium with genetic material and “hijack” the cell’s machinery into producing virus particles.33 Although different viruses can reproduce in different ways, this infection cycle commonly ends when so many viruses have been produced that they “explode” out of the bacterium, killing or “lysing” their host, and spreading into the environment to restart the infection cycle in a new cell (Figure 2).34

Figure 2. Bacteriophage virus infecting and lysing its host bacterium35

In the 1920s, d’Hérelle successfully developed this viral capacity to lyse their hosts into an oral treatment for bacterial dysentery,36 still a major cause of mortality for children under the age of five.37 The publication of this success spurred commercial laboratories in the United States, France, and Germany to begin producing clinical applications of phage therapy. While many factors led the Western world to largely abandon phage therapy, republics in the former Soviet Union continued to develop phage therapeutics and employ them in routine medical treatment. Today in Tbilisi, Georgia, home to the Eliava Institute, one of the oldest phage research institutions in the world, “phage cocktails” combining ten or more different viruses can be purchased as an over-the-counter treatment for a variety of ailments.38

Both of these bacteria-killing treatments were developed by observing the natural world in action. When humans adapt existing strategies in nature for solving human problems, we call this “biomimicry.” Popularized by Janine Benyus in her 1997 book of the same title, these “innovations inspired by nature” include solutions for food systems, healthcare, energy, and a whole host of other existential crises currently facing planet Earth.39

This concept is particularly resonant for an environmental science unit grounded in biodiversity. If humans are looking to the diversity of the natural world for inspiration to its problems, it adds urgency to preserve that biodiversity currently under assault. Although not adopted by the International Union of Geological Sciences, the era we currently live in is popularly called the “Anthropocene,” named for human beings and the detectable impact our actions have had on the geologic record.40 One of those impacts is “the sixth mass extinction.” As evidenced by fossil records and other measures of historic biodiversity, Earth has gone through five periods of sharp decrease in the number of living species.41 Since the 1950s, measurable decline of biodiversity due to human action has become so significant as to warrant comparison to a rate of species loss not seen since the extinction of the dinosaurs.42 If we hope to develop further life-saving solutions inspired by the living world, it is essential that world stays alive.

Viruses: Not Alive But Still Evolving

With a little scientific wordplay, viruses are technically immune to this human-mediated assault against life as we know it; unlike bacteria, viruses are not considered alive under most scientific definitions of life. At the molecular level, virus anatomy is a protein “coat,” called a capsid, that is filled with nucleic acids, either DNA or RNA.43 Although there are many crucially important modifications to this basic blueprint, even the most complex viruses are ultimately very simple compared to the molecular mechanisms of a single cell.44

And, at present, having cells is one of the fundamental requirements for life. Another viral failure in the test for life is that viruses do not have a metabolism. They do not obtain energy or “grow” once their protein coats are assembled. Nor, by most measures, do they maintain a stable inner environment relative to external changes, called homeostasis, and they cannot reproduce on their own. In order to make more viruses, they need to infect a host and use its cellular machinery to make more copies of themselves.45

Despite these disqualifications from the living, one of the life characteristics they do qualify for is the capacity of their genetic material to undergo change.46 An important feature of natural selection as a mechanism for evolution is that it happens in the context of a specific environment. How viruses originated is still a major mystery in the history of Earth.47 However, evidence of bacterial life on Earth exists as far back at 3.77 billion years.48 At least one team of researchers has hypothesized that viruses may predate the Last Universal Common Ancestor, which would be older than the evolution of bacteria.49 This suggests that viruses and bacteria may have shared an environment and exerted selection pressure on each other’s genomes for more than three-billion years. Given a few billion years of coevolution, phage genomes have developed to the point that they typically infect only a narrow range of host bacteria.50 This means the virus can only reproduce if it encounters the one or two strains of bacteria it “grew up with” and has the complementary genetic code for successful binding, infection, and replication.51

This narrow range of host infection presents benefits and challenges to using phage therapy relative to chemical antibiotics.52 Many pharmaceutical antibiotics are considered “broad spectrum,” they are able to kill many different species of bacteria. For a long time, it was not necessary for a medical practitioner to establish exactly which strain of bacteria was infecting a person.53 While this saves precious time in the fight against infection and was for many years highly effective, the pathogenic, or harmful bacteria, are usually a small minority relative to the beneficial and innocuous bacteria that call the human body home.54 As broad-spectrum antibiotics move through a human system, they do not distinguish between bacteria that are causing illness and which ones are providing essential health services. The consequences of this indiscriminate “bactericide” are not yet well understood, but early childhood applications of antibiotics have been correlated to gastrointestinal, immunologic, and neurocognitive conditions.55

As we continue to learn more about the relationship between the microbiome and human health, phages that infect and kill only one particular species of bacteria could be hugely beneficial. That narrow infection range of phage-derived antibiotics preserves the nonpathogenic microflora, targeting only the undesirable species. However, in the United States, this necessity for “exactly the right phage” leads to delayed approval and application for human use. Due to safety restrictions by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, extensive time and resources are required to identify which strain of pathogenic bacteria is infecting someone, then perform the necessary experiments to find a safe and effective phage complement that target and lyse the bacteria specifically.56 This process is likely to improve as more trials are publicized and a more well-characterized phage library is made available.57

But You Said, “Organisms We Seek to Control Will Evolve Resistance”

Yes, the American Society for Microbiology did say that resistance will evolve in any organism we try to control. That includes microbes developing resistance to bacteriophages.58 Observed both in the lab and in clinical treatment, bacteria with phage resistance mutations emerge rapidly and frequently.59 As of 2018, in the four human trials that monitored for the emergence of phage resistance, three reported successful bacterial resistance. In one of those trials, a multiply-drug resistant strain of Acinetobacter baumannii causing pancreatitis was selected for clinical treatment using two, four-phage cocktails that were effective in vitro. Although the infection was significantly reduced, bacteria resistant to all eight phages were isolated after eight days in vivo, and a ninth phage was required to fully clear the infection.60

Resistance to one phage can also confer resistance to similar phages or even pharmaceuticals that target the same mechanism. In a study by Kortright et al., researchers exposed E. coli to two phages and albicidin, a chemical bacterial inhibitor. All three of these antimicrobials interact with Tsx porin, an outer membrane protein channel. In each of the twenty-nine bacterial mutations that conferred resistance to one antibacterial, the mutation conferred cross-resistance to all three. Genetic analysis of the bacterial mutations showed that all of the mutations caused at least one change in the tsx gene, which codes for the structure of the porin.61 In a laboratory study by Wright et al., Pseudomonas aeruginosa was tested against different phages and cross-resistance was again observed due to changes in external structural features, likely phage binding sites including liposaccharides (LPS) and type IV pilus proteins.62 This type of cross-resistance is receptor specific. Each of the antibacterial mechanisms interact with the same external features.

Generalist cross-resistance has also been observed. In the P. aeruginosa study above, phages were selected that bind to either LPS or pilus proteins. Mutations conferring general resistance to both modes of attachment were identified in transcriptional regulation genes rpoN and pilS. PilS is involved in the expression of external pilus proteins by activating rpoN. The gene rpoN (RNA polymerase, nitrogen-limitation N) encodes for a regulatory protein, sigma54 (s54), that is involved in the transcription of over seven-hundred genes. This involvement in a wide variety of bacterial functions makes it more difficult to identify the pathway between mutation and the resistance phenotype; however, this type of general mutation only occurred in 10% of observed strains, suggesting it is rarer, in part because there is only one copy of rpoN in the bacterial genome compared to the several genes required for synthesis of LPS and pilus proteins.63

How these resistance mechanisms evolve and disperse is an important research step before wide-spread clinical application of phage therapy.64 Most resistance mechanisms are the product of random mutations, but they can also arise through adaptive immunity in which bacteria incorporate strings of viral nucleic acids into their genome through the CRISPR-Cas system to recognize the virus during its next infection attempt and initiate a type of bacterial immune response.[65] After a resistance mechanism originates in an individual, the bacteria can then pass on genetic material both to their offspring or to members of the same generation through horizontal gene transfer.

Resistance-Resistant Features of Phage Therapy

Despite the rapid evolution and spread of phage resistance in bacteria, phage therapy offers mechanisms that can delay66 or limit resistance acquisition,67 prevent phage resistance from becoming more widespread or induce other detrimental features into the bacterial population.68 Although these are promising features of phage therapy that are not available through chemical agents of control, they must be thoroughly researched and used cautiously to prevent a reoccurrence of the widespread resistance currently underway as a result of industrial scale misuse of pharmaceutical antibiotics.

Although viruses are not alive, their genetic material has been coevolving with their bacterial hosts for perhaps billions of years.69 One proposed mechanism of delaying bacterial resistance takes advantage of this coevolutionary ability to “train” phages to kill successive generations of bacteria in order to preemptively “evolve” them ahead of any resistance mechanism the bacteria might develop.70 This method is hypothetical and contentious. An alternative hypothesis is that rather than developing phages that are effective longer, the bacteria will evolve several resistance mechanisms at once. When tested in the lab, however, the coevolved phages successfully delayed bacterial resistance by two to four weeks, a significant gain of function if this finding is can be replicated in an in vivo application of phage expected to clear the population within a few days.

One of the most interesting applications is the ability to reintroduce antibiotic vulnerability in bacteria that were previously antimicrobial resistant. Called a fitness trade-off, it means that a mutation conferring one survival benefit may reduce fitness in some other context.71 There are two prominent ways this has been adapted in the therapeutic context. One method identifies features about the bacterial population that improve its ability to spread, called virulence, or its lethality upon infection, called pathogenicity. An example with demonstrated impact on virulence is to select a phage that adsorbs to LPS. Many bacteria have a polysaccharide “capsule” that can hide them from macrophage digestion during an immune response. If a bacterium contains a mutation that removes or down-regulates the LPS binding site, it can interfere with capsule production and make the bacterium more vulnerable to detection and engulfment by the immune system.72

The other method combines phage therapy and pharmaceutical antibiotics. In this strategy, a mechanism of resistance in a drug-resistance bacterial strain is identified. For example, one broad spectrum resistance mechanism is the development of “efflux pumps” that selectively remove chemical antibiotics from bacterial cells and extrude them back into the environment.[73] If a phage is designed to target the efflux pump as a binding cite, the next generation of bacteria that survive the phage may do so by developing a mutation that renders the efflux pump ineffective, restoring its susceptibility to the traditional antibiotic. There are several identified resistance mechanisms that may reintroduce antibiotic vulnerability under selective pressure by well-chosen phages.

Concluding Remarks: Genetic Engineering and DNA as Commodity

One of the factors that limited adoption of phage therapy in the United States was that U.S. patent law is inapplicable to “the natural laws, mechanisms or objects which already exist independently of human beings.”74 Bacteriophages occur naturally. Although it is possible to patent unique applications of phage, called a process patent, the viruses themselves could be used by anyone who discovered them. Although the urgency of antimicrobial resistance is one factor spurring reinvestment in phage therapy,75 another factor is the advances in biotechnology and genetic engineering.76

During the second half of the 19th century, the price of steel decreased from $170 per ton in 1867 to a mere $14 per ton by 1900.77 In the 20th century, Moore’s law described how the processing power of microchips nearly doubled every year from 1975 to 2012. Now, in the 21st century, we are in the midst of a “Carlson curve.” Named for Dr. Rob Carlson at the University of Washington (who does not like the namesake), it observes that the cost of sequencing and synthesizing base pairs of DNA, the biological “blueprint” of life, has decreased exponentially since the ground-breaking and multi-billion dollar Human Genome Project. This means more researchers have the ability to quickly and inexpensively characterize and test phages using whole genome sequencing and more efficient technologies for growing microbes and simultaneously, large-scale screening.78

Although not widely discussed in this paper, another consequence of the age of biology is the manipulation of living things, as the final product or themselves as technologies of change. The most effective capacity humans now have for genetic modification is itself derived from the billion-year-old evolutionary struggle between viruses and bacteria.79 Called CRISPR-Cas9, this is a partnership between a nucleic acid target sequence and an enzyme that cuts the targeted sequence. It was originally discovered in bacteria to incorporate strands of phage DNA into their own genomes as a type of immune response; the enzyme would destroy any viral DNA that matches sequences previously encountered and encoded in the bacterial genome. When intentionally “programmed” by human-designed guide RNA, this system can induce single-point changes into DNA with an accuracy unmatched by earlier technology.

However, genetic engineering makes a commodity of the very molecules of life. Humans are discovering naturally existing viruses that combat antimicrobial resistance and genetically modifying them to patent ownership of their useful properties.80 How is DNA ethically different from steel? What consequences are invited by applying the same structures of ownership and profit margin that so devastated previous centuries? Can ninth grade students come to a consensus about what is fair and just in the world of synthetic biology and can they be agents of change themselves? By exploring the role of viruses and bacteria in their environment, students will have a better vocabulary for what is manipulated during genetic engineering, i.e. change the DNA “code” and you change a protein and its potential functionality. What might make them trust a process of genetic engineering, and how do they perceive balancing “good hearted intentions” with pursuit of the profit margin and who has access to these technologies?

At the level of organisms or DNA base pairs, biodiversity is a way to measure and compare the variety of living things in a particular area. Earth’s environments contain magnitudes more diversity when including the microbial world; but, while they often go unnoticed, these microbes have been an essential part of humanity’s impressive, if brief, success on planet Earth. They will also prove indispensable for its continued survival. As extractive capitalism and unregulated fossil fuel consumption continue to change Earth’s climate with devastating consequences for health and biodiversity, microbial genomes offer a several billion years’ evolutionary history of adapting to existential threats. That much time spent refining genetic code has created an Earth spectacularly full of elegant survival systems. However, if human action continues to drive species extinction at a rate unprecedented in last sixty million years of geologic record, that “library of life” will no longer be available for application to human-scale problems. Teaching young people the biomolecular basis for uncovering this “hidden treasure” of genetic diversity is not just an academic framework for the classroom; it has profound implications for how individuals live in and relate to their world.

Comments: