The Process

The intention of the sequence of modules and classroom activities is to serve as template or guide for the biography unit and can be adapted to suit another class situation or school environment. While the unit is intended for high school students, middle school teachers could replace Maus with a biography more suited to a middle school grade level. The activities are designed for classes that meet on block scheduling, every other day for 90 minutes at a time. The length of the lessons can vary depending on the depth of a classroom discussion. Students receive credit towards their grades by participating. The reading, writing prompts, and oral presentations all address the state standards in English/Language Arts. In addition to Language Arts standards, the module-based lessons on biography touch on a number of Virginia state-mandated standards of learning concepts, and are designed to complement and reinforce core subjects by providing alternative experiences: i.e. developing literacy skills using computers/technology, and learning outside of the academic classroom.

Writing

The unit begins with Writing where students will recognize traditional reading and writing lessons. This is also the point where students will begin to create the biography container. This is an imperative process in the initial stages of biography because it establishes the significance and emotion of stories. In the Writing module students will create a class definition of biography; read, critically analyze, and discuss Maus; research, interview, and write a biography on an elder (either a family member or someone a student has a connection with).

Lesson One: Defining biography

Objectives:

- to access prior knowledge by revisiting biographies students might have been introduced to in elementary/middle school.

- to have students work individually and collaboratively on creating a definition of "biography".

Step1: Prior Knowledge

Have a variety of elementary and middle school biographies that students might remember. Conceptually, the idea is to move students from the macro to the micro. The biographies should be ones students would recognize from elementary school: basic, factual narratives of famous people. Some wonderful examples of elementary school biographies are a Picture Book of Ben Franklin by David Adler; George Washington's First Victory by Stephen Kenskey; and Abraham Lincoln's Hat by Martha Brenner. Any of these threes texts can be read fairly quickly to the class. Some exceptional middle school biographies include: Twice Toward Justice: The Story of Claudette Colvin by Phillip Hoose; The Last Seven Months of Anne Frank by Willy Lindwer; and East Side Dreams by Art Rodriquez. Begin to chart some of the responses and have students take notes about each text and about some of the similarities and differences of each level of text. Examine the choices made in terms of title, cover illustrations, font and size, page number and size of the book, summarization on the back. After comparing and contrasting the elementary and middle school biography examples, show students a copy of Maus. In the same way elementary and middle school biographies were compared and contrasted, have students do the same for Maus. Explain to students that Maus is the biography that will be read for this unit and how it is an illustrative and graphic amalgamation of elementary and middle school biographies, but the content definitely geared for upper school students.

Step 2: Individual Definition

First you'll be working individually with students to have them generate a group definition. Write the word biography in a large space in the classroom (i.e. overhead projector, white board, chalk board). Ask students to write out their individual definition of biography in their notebooks. You may want to write the question, "What is a biography?" underneath the word biography on your overhead. Give the students two to three minutes to write. Discourage students from looking in the dictionary or computer. Ask them to trust their knowledge.

Step 3: Present

After two minutes or so, ask for volunteers to share their definitions. Write the different definitions on the overhead as students share them. Ask students to look at the definitions that have already been given. The class will agree upon useful definitions.

Step 4: Combining Definitions

Students may like a particular answer and want to make some changes to it. Since this a class definition, go ahead and make the changes as appropriate, checking in with students to make sure it is functional. From those definitions that the students consider useful, the class will create one definition that will establish the properties (and rules) of biography.

Step 5: Group Definition

When you have come up with one single definition, read it back to the students. (Some students might come up with the definition the first time they try together, "A biography is a true story about a persons life, but it is written by somebody else.")

Step 6: Dictionary Definition

Now, ask a student to look up biography in a dictionary. Have the student read it out loud to the class. How close is their definition? Is there anything they would like to add or delete? Do this with them on the overhead, or whiteboard, as they will use their definition as the foundation of biography throughout this unit. Do not allow students to use the dictionary definition, as they have worked hard to put their knowledge and ideas into their own words. This exercise is as much about the collaborative process of understanding the ownership of language as it is about the definition of the word, biography.

Lesson Two: Maus by Art Spiegelman

Objectives:

- identify some of the major events of the Holocaust as recounted by Vladek Spiegelman

- identify themes and issues presented in the book

- identify character traits of the major characters

- analyze the exchange of feelings between Art Spiegelman and his parents

- analyze the use of animals to represent races/nationalities

- analyze the changes of time that occur in the chapters and the turning point(s)

- analyze the use of graphics in the book and their relationship to the story

Step 1 – Introduction of Maus and the graphic novel genre

I will introduce the book to the class and discuss the graphic novel genre. Examples of other graphic novels and comic books may be shown. Students are asked to draw on their experiences with comic strips, comic books, and graphic novels to develop characteristics of each; these may be displayed in a graphic organizer or in table form. After giving some background information on Maus and its author, ask students about their knowledge of the Holocaust. Use a journal prompt to learn what students know about the Holocaust and what they want to learn, or how they think comics can be used to treat a serious topic.

Step 2: Prologue Class Read

The entire class reads the prologue and the first chapter of the first volume. When students have read these sections, the teacher initiates a discussion following previously agreed upon rules regarding group discussions. Because literature circles are reader response centered, students should direct the discussion with teacher guidance.

- I might begin the discussion by asking the class what their initial impressions are about the combination of comics and the serious topic of the Holocaust or what they think about Spiegelman's use of animal heads with human bodies as characters. The teacher should encourage students to use specific examples from the book as they draw conclusions and offer observations and opinions.

- Students might add words with which they are unfamiliar to a class list posted on the bulletin board or in their journals and research definitions.

- I will have a list of discussion questions ready in case the discussion bogs down (see a suggested list by chapter near the end of this section).

- The discussion should take no longer than about fifteen to twenty minutes and should provide a model for discussions that will take place later in small groups. At the end of the discussion, the teacher divides the class into literature circles of four to six students, grouping students heterogeneously where possible. These groups will meet as scheduled to discuss the remaining chapters of the book.

Step 3: Group Discussions

Over the period of the scheduled reading dates and discussion dates, students read the chapters of the books and meet to discuss them. Each meeting will focus on a specific chapter (or chapters). During these small group discussions, the teacher may observe in order to keep students focused and for purposes of assessment, but the discussion should be student centered. Students will journal their responses to the reading and to the discussion process. Journal prompts may be keyed to specific chapters to focus student thinking if necessary

Step 4: Visualizing Key Elements

Students will be asked to visualize key elements of the book:

- Character maps (see an example at )

- Table showing parallels between the public events of the Holocaust and the private life of the Spiegelmans

- Table or graphic organizer showing examples (with page references and/or quotes) of the themes of irony, intergenerational conflict, depression and suicide, guilt, dominance, racism, etc. Templates of graphic organizers may be found at http://www.eduplace.com/ graphicorganizer/ and at http://www.graphic.org/goindex.html, or the students can use Inspiration or Kidspiration software if available.

- Graphic organizer with the animal figures used in the books, the racial/national groups they represent, and why Spiegelman might have chosen each animal to represent that racial/national group.

If time permits, students can research comic format in order to learn about the techniques and vocabulary necessary to better understand and discuss the comic artist's work. A knowledge of words like "panel," "frame," "gutter," "balloon," and "bleed," will give students a common vocabulary of graphic illustration technique. Considerable information on the technique of comic art can be found at the web site of the National Association of Comics Art Educators ( http://teachingcomics.org ). At this site, "The Creation of a Page Tutorial and Guide" by Tom Hart is a good introduction to the process of creating comic panels.

Step 5: Culminating Activity

Individuals or groups can create their own story in graphic novel format. The story might be based on one of the themes used in Maus. Brainstorming, researching, prewriting activities, storyboarding, rough drafts, etc. as outlined in Tom Hart's web tutorial (listed above) should be employed to insure a carefully structured product.

Assessment: Assessment of a literature circle unit may be both formal and informal. The teacher's observation of each student in discussion groups can be used as an informal assessment. Student journals, self-reflection, and performance on worksheets and projects provide more formal forms of assessment. I have included chapter-based discussion prompts in the appendix in order for the groups to stay focused and for those students who are having trouble reacting to a reading.

Lesson Three: Biography Writing

Students will be writing a biography on an elder in their family or one whose connection they greatly admire. The following specifications are merely suggestion, so be at liberty to adjust them according to your student population: five paragraphs, typewritten, minimum of two direct quotes from their interviewee.

Choose a family elder – Students will pick an elder who has led a very interesting life, but one they may know very little about. Students will be spending time with this person and have to write about them so they should pick an elder in their family who is interesting, one they admire. Think about that person – students are to write down questions they have about their interviewee: What did they do? How have they made an impact on our world today? What do they feel is the greatest invention in the past forty years? In what ways can a young adult be like them? Gather information – students should try and find as much information on their elder as they can. This includes artifacts such as letters, photographs, clothing, etc. Take notes – Students will record facts and information as they find them. They can write these on index cards or in a special notebook with all of your research. Find a photo – Students should include a photograph or artifact to be included with their written biography.

Oral

The biographies of people in our families are rich resources of information about the past. They are living witnesses to history. To preserve this history and honor their stories, interviewing family members about the events at particular time periods in their lives can be a transformative experience for a student. Through the oral biography, a student can learn more about the hopes, feelings, aspirations, disappointments, family histories, and personal experiences of the person being interviewed. Finally, when a student shares his interview, a larger picture of the person, time, and place in question emerges an understanding of a neighborhood, of a family, of a generation, of a decade, etc.

Objectives:

- listening to recording oral histories from storycorp.org, tellingstories.org, doingoralhistory.org and watching

a mock interview in class

- recording and writing an oral history from a family member or community member.

- following the guidelines

- sharing the digitized interview with the class

Web resources: www.storycorp.org; www.doingoralhistory.org; www.tellingstories.org

Materials: Many cell phones, mp3 players, and cameras are equipped with a recording device. While the production value does not have to be great, students will have to have recording device to record their interviewee. During the interview process it important that students have composition book to take notes and a list of questions they will ask their interviewee.

Software: Audacity is the most prominent computer software available to transfer the recorded interview on to a computer. It is a free download and it is available for both Mac and PC computers. If the recording device does not have a USB sync, then you can record directly to a computer using the built-in microphone.

Introductory Activities:

- Before the oral biography project begins I introduce students to the history, theory, and practice of oral storytelling as a form of history and biography. I think the best way for a class to understand the compelling nature of oral storytelling is to listen to examples. The above mentioned web resources offer a variety of excerpts from their archives. The more a student hears the specific nature of an interview, he begins to understand that the intention of the oral history is to identify a particular timeline or moment in the interviewee's life.

- It is also important to model the interviewing process. I would choose a recognizable professional teacher, colleague to interview. Often a student will contextual a teacher only in a school environment, but this offers the chance for the student to experience the teacher as something beyond the school environment. Conduct the interview in front of a class with a recording device and questions prepared. I am not merely modeling the type of questions to ask, but I am modeling listening and note-taking skills as well.

Procedures for the student oral interview:

Step 1: Select the Interviewee

- Decide what period of history (the lifetime of a living person) the project will cover—childhood, early adulthood, a certain decade, a period in the history of a town, etc..

- List several people that would fit into the identified era.

- Narrow the choice to one or two. Contact the chosen person and, if necessary, have him sign a permission form to have the interview taped for a specific project, explaining the intention of the interview and how it will be used.

Step 2: Complete Pre-Interview Research

- Get as much information about the timeline, topic, and the person as possible (this information can from family members, library sources on the community.

- Prepare a general list of specific questions and topics. Use open-ended questions more than Yes/No questions to avoid getting very short answers.

Step 3: Practice

- Practice using your equipment so the technology during the interview will go smoothly.

- Practice an interview with a friend, family member, or classmate as a trial run. The interviewer should do less talking than the person being interviewed.

- Pack pens and paper in case technology fails.

Step 4: Conducting the Interview

- Select a quiet place to use for the interview (no TV, radios, barking dogs, etc.).

- Put the interviewee at ease because people are often nervous about being taped; they are afraid their memory may fail or that they will be boring.

- Ask one question at a time.

- Do not interrupt the interviewee.

- If the interviewee strays from the question, bring him/her back with a comment or question.

- If the interviewee gets tired or fidgety, you can close the interview and reschedule more time later if needed.

Step 5: Processing

- Digitize the oral interviews using Audacity software.

- If an interviewee has spoken on several topics of interest, edit those stories into short files of ninety seconds each.

Project Assessment:

- The interviewer will choose and interview one person who is pertinent to the topic covered.

- The interviewer produces written information obtained from family or public sources.

- The interview produces a list of possible questions and topics to be covered that are pertinent to the assignment.

- The interviewer returns with an audible tape of the interview, and/or notes taken during the interview.

- The interviewer produces a digitized oral biographical narrative based on the interview that contains correct statements and information.

- The interviewer shares the audio with the class.

Digital

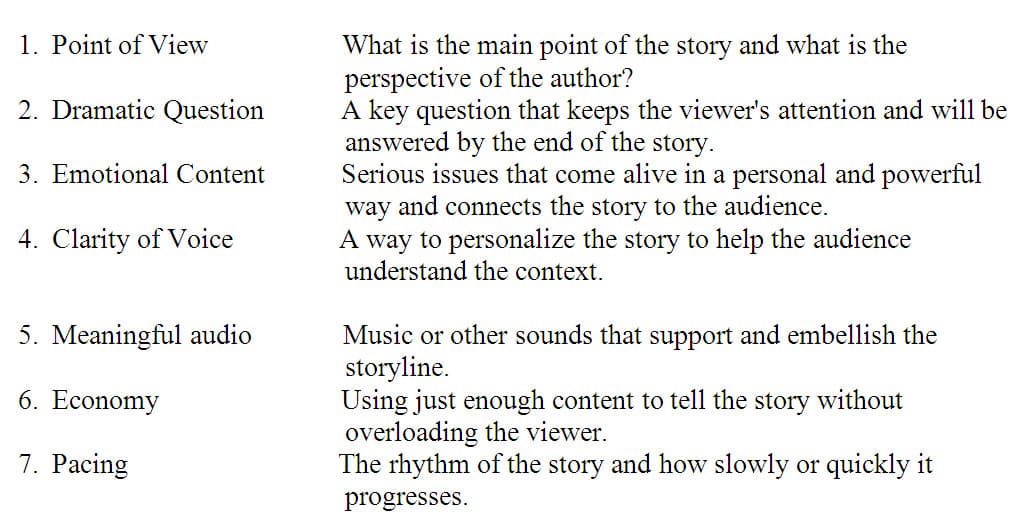

The primary motivation for a student to create a digital story is for him to experience biography as an amalgamation of the written, oral, and visual. The guiding principles of the digital biography is based upon the seven elements of digital storytelling developed by Joe Lambert at the Center For Digital Storytelling. (10)

Tutorial: There are a variety of websites that offer a simplified way to create a digital biography. Many of these websites are very basic, and therefore are very limiting in terms of the depth of a project. Such sites might serve as a fine example and place for a student to experiment and play, but eventually a student will want to be more creative with his storytelling. Microsoft has a free downloadable tutorial of Movie Maker and Photo Story at www.microsoft.com/education/teachers/guides/digital_storytelling.aspx . The tutorials are easy to follow and either program is sufficient for a student to be creative with his digital biography. For the MAC platform, iphoto and imovie work well. There are a variety of tutorials available on the web. I also suggest investing in Final Cut Teachers Edition. Prices will vary and it is tremendous too to teach a student as it requires more skill and precision than any of the other programs.

Process: The process in preparing a digital story is very similar to WRITING and ORAL. The student will have to decide upon an interviewee. The student will maintain the same interviewee throughout the semester. If not, it is important that the same criteria be followed for choosing an interviewee: an elder, a family member or community member. It is also very important during this stage that the student gather as many artifact as possible from his interviewee. Artifacts can include photographs and letters but it can also include items that can photographed such as a car, a drinking glass, etc.. These artifacts will become the basis for the visual story. If it is appropriate, a student can also use a stock or downloaded images as well. The student must seek permission before using photographs which are on the internet. The student may use clips of the audio interview with his interviewee, but the majority of the digital story must be in his voice. Ambient sound such as music and sound effects may also be used so long as they do not detract from the theme of the story.

Assessment: It is often difficult to assess the work of a student on this type of project because he is being introduced to an entirely new concept. Technology glitches can also make things more difficult. The rubric I have created is based upon the seven elements, but can be modified as needed.

Portfolio

The student portfolio module is the culmination of a sustained inquiry of biography. It pieces together the various components of biography the student has studied and completed into a community presentation. Using the definition biography as the "container" that can hold the emotion of the biography, a student can share with the community his understanding of Maus; the process of creating questions connected to the time-line of his interviewee; the experience of interviewing his subject; his recorded and visual biographies. In choosing carefully a person for a biography they care deeply about and having a stage to present this person and the work, students gain a sense of their own power as learners, historians, and most importantly a biographers.

Objectives:

- a student establishes a collection of work he has completed over the course of the unit.

- school and community members are invited to the portfolio presentation.

- students follow the rubric criteria and show several revisions of their work.

- school and community members look carefully at the work and offer constructive feedback.

Assessment: The Portfolio is a style of assessment that is not to be graded. It is about fostering an intergenerational, reflective, and democratic community that is committed to the learning development of youth and has a vested interest in engendering stories of profound yet unsung lives.

Step 1: Public Presentation

After a student has edited their oral and digitized work into a final completed product, he presents a body of work from the unit that he feels showcases his level of understanding. The invited community members should include each interviewee, family members, a school administrator, departmental instructors, school personnel including secretaries and maintenance, and a district representative. This type of presentation is best suited for a block schedule of ninety minutes (if there are too many students in the class, I would vote on eight to ten students to present. It is important that these students know they are representative of the class). Make sure each student follows the checklist of criteria that needs to be included in the presentation. Each presentation should be longer than seven minutes, followed by a question and answer time.

Step 2: Portfolio Roundtable

Students will have collected a variety of artifacts to help them reflect on the life of their interviewee. These artifacts may include journal entries, photographs, and letters. Over the course of the unit students have also collected a variety of records which have helped them reflect on their own intellectual and artistic growth such as storyboards, interview questions, revised write-ups, and digital rough-cut edits. Students publicly present this body of work at a roundtable style of assessment. The interviewee, family, school, and community members listen and view the work completed by the student. Following this, there is a question-and-answer session where a student has the opportunity to respond to community inquiry, present new perspectives, and introduce his subject.

Holly K. Banning

January 21, 2011 at 9:00 pmUnit Cited

Dean, In writing a paper on the subject of 21st century literacies, I found your unit to be very useful. I cited it and highly recommended the adaptation of this versatile unit to upper elementary and middle school teachers in integrating technology into the writing process. I also acknowledged its value in connecting with the culturally and linguistically diverse student by using an engaging literacy practice (digital storytelling) meaningful to his or her life.

Comments: