Rationale

The Pittsburgh Public Schools make up the second largest school district in Pennsylvania. Approximately 28,000 students attend grades K-12 in 66 schools. I teach 7 th grade math in a 6-8 middle school. We are considered a magnet school, which means we maintain an equal racial balance of our 330 students. All our students live in city neighborhoods, and the mean family income is about 64% of the Pennsylvania average. While we face many of the challenges of inner-city schools, we have not had to deal with excessive truancy or violence.

My students are what I would call "typical" 13-year-olds. Each year, I have about three or four gifted students in each of my classes. This past school year, I did not have any inclusion students, which is unusual since we are a full inclusion school. So I had classes of average-intelligence students. They are much more interested in socializing than in doing schoolwork, and definitely not very interested in math. Since we are a magnet school, a bit more parental involvement occurs than in some of the neighborhood schools, and consequently I think our students are slightly more likely to do their homework and a little more worried about their final grades.

The curriculum I teach is Connected Math 2 (CMP2). The goal of CMP2 is to develop student knowledge and understanding of mathematics that is rich in connections; connections between ideas and grade levels, between different subject areas, and connections within the community and the world outside of school. The CMP2 curriculum is organized around interesting, real-life problem settings. Deep understanding of mathematics is acquired through observations of patterns and relationships. The seventh grade curriculum moves into pre-algebra, with an emphasis on ratios and proportions.

CMP2 develops four mathematical strands: Number and Operation, Geometry and Measurement, Data Analysis and Probability, and Algebra. Most of the goals are revisited in later units and subsequent grade levels throughout the curriculum.

The seventh grade CMP2 curriculum I teach includes the following seven units:

Variables and Patterns (Algebra): describing patterns of change between two variables,

constructing tables and graphs, using algebraic symbols to write equations.

Stretching and Shrinking (Geometry): identifying similar figures by comparing corresponding parts, drawing shapes on coordinate grids and using coordinate rules to stretch and shrink those shapes.

Comparing and Scaling (Number): using ratios, fractions, differences, and percents to form comparison statements, scaling a ratio, rate, or fraction up or down to make a larger or smaller one, applying proportional reasoning to solve for the unknown part.

Accentuate the Negative (Number): comparing and ordering rational numbers, developing algorithms for adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing positive and negative numbers, using the Distributive Property.

Moving Straight Ahead (Algebra): constructing tables, graphs, and symbolic equations that express linear relationships, solving linear equations.

Filling and Wrapping (Geometry): understanding volume and surface area, exploring prisms, pyramids, cones, cylinders, and spheres, extending understanding of similarity and scale factor to 3-D figures.

What Do You Expect? (Probability): interpreting experimental and theoretical probabilities, determining the expected value of a probability situation.

As you can see, our 7 th grade curriculum covers a variety of mathematical concepts, with the main emphasis on developing algebraic reasoning. Currently, students have ten periods of math a week; two periods per day (about 90 minutes total), usually (but not always) blocked together. While there is time to complete all seven units, time is always an issue and we follow a fairly strict pacing guide.

The second unit of the 7 th grade CMP2 curriculum is "Similarity Transformations: When Shapes Shrink or Grow" (Stretching and Shrinking). In this unit, we graph a character named Mug, a member of the Wump family. Mug is basically a trapezoid with legs and a face. By applying different transformations to the original coordinate points, for example (x, y) → (2x, 2y) or (x, y) → (3x, 3y), the students transform the original Mug into larger members of the Wump family. They also move Mug around on the grid, or create "imposters" that are misshapen and therefore not similar.

Fig.1: Mug Wump in his original shape

Stretching and Shrinking is a rich exploration of what it means for two or more figures to be mathematically similar, and by working within the context of a family of strange, gnome-like characters, students get to have a little fun while investigating all aspects of similarity.

In my curriculum unit, I will expand my students' exploration of the Wump family by introducing other types of transformations such as reflections and rotations. Symmetry is one area that is not covered in the 7 th grade CMP2 curriculum. There is one geometry book in 6 th grade, Shapes and Designs, in which two pages are devoted to symmetry. In the 8 th grade, there is an entire unit dedicated to symmetry (Kaleidoscopes, Hubcaps, and Mirrors), but that unit is scheduled near the end of the school year and is often not even taught because of time constraints.

According to the Pennsylvania Academic Standards for Mathematics, by the end of eighth grade, students should be able to:

- Use simple geometric figures (e.g., triangles and squares) to create, through rotation, transformational figures in three dimensions

- Analyze geometric patterns (e.g., tessellations and sequence of shapes) and develop descriptions of the patterns

- Analyze objects to determine if they illustrate tessellations, symmetry, congruence, similarity and scale

Overall, it seems that symmetry is not such a big deal in the scheme of middle school math, and certainly not even addressed in seventh grade.

So why teach symmetry to seventh graders?

Because symmetry is everywhere. Probably the most easily identified property of a figure, symmetry is about connections between different parts of the same object. Most students already have an intuitive understanding of symmetry; they can identify a symmetrical object and they can find repeating patterns. More sophisticated thinking is required to actually confirm symmetry and to construct figures with given symmetries.

Symmetry can be defined in terms of transformations of an object. While we are

transforming our Wumps by making them larger, smaller, or in some way misshapen, this is not considered what is termed isometry or congruent transformations. My goal for this unit is to work with our basic Wump figure, and later on with another simple geometric shape of the students' own design, and explore simple transformations of our figure through reflections, rotations, translations, and glide reflections.

Before we can go further in our discussion of symmetry, some basic key terms should be explained:

transformation: the transformation of a figure is achieved by applying a rule for moving the points of the original figure to obtain the new figure; the transformed figure is the collection of the image points of the original figure.

image: a copy of an original figure, made by a transformation

isometry: a congruent transformation of a figure. All distances are preserved in isometries; that is, for example, if point A and point B are 2 cm apart in the original figure, they will still be 2 cm apart after an isometric transformation. Equivalent terms for isometry are rigid motion, congruence transformation, and distance-preserving transformation.

line of symmetry: a line that divides a figure into halves that are mirror images

parallel: parallel lines are lines that never intersect; two non-vertical lines in the (x, y) - coordinate plane are parallel if and only if they have the same slope

perpendicular: two lines that intersect and form right (90°) angles

symmetry: when a transformation preserves a figure, it is called a symmetry of the figure. The figure is said to be symmetric under the transformation.

Let's now begin a (very simplified) explanation of what symmetry is all about. If you open a symmetry textbook, written for students or mathematicians, it can be very intimidating. And while I feel quite intelligent carrying books like this around with me, the information for the most part is way above my head. So I'll attempt to make this as accessible as possible to my readers.

There are four kinds of isometries that we will be exploring in class: reflection, rotation, translation, and glide reflection.

Reflection symmetry is also called mirror symmetry, because if a line is drawn through the center of the object, one side is the mirror image of the other, across the line. If you think of the capital letters A, M, or Y, for example, you can see that they each have a reflection symmetry across an imaginary line running vertically through the center of the letters. The capital letters B, C, and D have reflection symmetry across a horizontal bisecting line. For all these letter examples, a point on one side of the line will exactly match the corresponding point on the other side. A point and its image under reflection will lie at the same distance from the line or axis of reflection, and the line connecting them will be perpendicular to the axis.

Reflections are the most fundamental isometries, because any other isometry is a combination (the technical term is composition) of them.

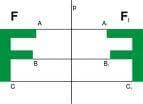

A reflection can be specified by giving the line of symmetry. If you look at Figure 2 below, you can see this. The big block letter F is reflected across line p. Point A and its image point A 1 lie on a line that is perpendicular to the line of symmetry and are equidistant from the line of symmetry. The same thing occurs with points B and B 1, and points C and C 1.

Fig. 2: Reflection symmetry

Rotation symmetry involves rotation (by other than a full turn) around a center point of the original figure. The rotation is a symmetry of the figure if it preserves the figure. All figures have what is called an identity rotation, which is what happens when you make one complete turn (that is, a 360° turn). Any rotation that is not an identity rotation is called non-trivial.

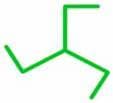

A rotation can be specified by giving the center of rotation and the angle of the turn. In the simple figure shown below, if each "leg" is rotated 120° around the center point, the figure is preserved. So rotation by 120° around the center is a symmetry of the figure.

Fig. 3: Rotational symmetry

A translation is a slide on a plane along the path of a straight line. It is described by giving the direction and the length of the slide. This can be done by drawing an arrow with the appropriate length and direction. If you draw the segments connecting points to their images, the segments will be parallel and all the same length. The length is equal to the magnitude of the translation. A translation moves each point of the plane the same distance in the same direction.

Translational symmetry occurs when a figure is preserved by a translation. Each translation has a direction and a distance.

Fig. 4: Translation

There is one more type of symmetry transformation we'll be using in class, and that is a glide reflection. Glide reflection can be thought of as a combination of a reflection and a translation, as seen in the footprints below:

Fig. 5: Glide reflection

In each type of symmetry, characteristics such as side lengths, angles, size, shape, and distance are maintained. This is all a consequence of distances between points being preserved, because if you know the distances between points of a figure, you know the shape completely. In fact, if you know the distance from a point to any three non-collinear points, you know exactly which point it is. Reflections, rotations, and translations relate points to image points so that the distance between any two original points is equal to the distance between their images. This is the key property defining an isometry. A figure is symmetric under a particular transformation if it is left unchanged by the transformation.

By using combinations of these different transformations of an object, you can create frieze patterns. A frieze is a pattern which repeats in one direction. If you look closely, you will see frieze patterns all around you: around the tops of buildings, on wallpaper borders, pottery, needlework, and so on. If you go on the NCTM's Illuminations website, you can play around and create your own frieze patterns. Frieze groups provide a way to classify designs on two-dimensional surfaces which are repetitive in one direction, based on the symmetries in the pattern. There are seven different frieze groups.

Students already know about similarity and congruence of figures from Stretching and Shrinking. They know that with similar figures, basic shape and angles will remain the same, but side lengths (and therefore distances) may be greater or smaller. In this unit, they will study reflections, rotations, and translations by measuring key distances and angles. This unit will show them how they can make patterns by moving the same figure around on the plane. They will learn how to describe a particular transformation so that another student could reproduce it exactly.

Comments: