Background Knowledge

Polygons

Triangles and quadrilaterals are the plane figures that we will work with in this unit. A triangle is a figure with three sides (line segments) that connect at three vertices. A vertex (plural form: vertices) is the point where two sides intersect. Where the sides intersect, an interior angle is formed inside the triangle. A famous fact of Euclidean geometry is that all three interior angles of the triangle add up to 180 degrees. A regular polygon is a figure with all sides the same length and all angles the same measure. For triangles, the equilateral is the regular polygon.

There are three types of triangles that are determined by the lengths of the sides of the triangle. An equilateral triangle has three equal sides, and three equal angles that measure 60 degrees each. An isosceles triangle has at least two sides of equal length (we can also call these sides congruent). This triangle will also have two interior angles congruent, because of the Isosceles Triangle Theorem. This theorem states, "If two sides of a triangle are congruent, then the angles opposite these sides are congruent." (1) A scalene triangle has no two sides congruent to each other, and thus no interior angles congruent.

A triangle can also be named for the kinds of interior angles it has. An acute triangle has all interior angles acute (measure less than 90 degrees). If a triangle has one obtuse angle (an angle that is more than 90 degrees, but less that 180 degrees), then it is called an obtuse triangle. A triangle cannot have more than one obtuse angle because the sum of two obtuse angles will yield more than 180 degrees, and this is not possible in a triangle , since the sum of all three angles is only 180 degrees. A right triangle has one angle that measures 90 degrees (a right angle).

Quadrilaterals have four sides and four vertices. Two sides end at each vertex. The sides should not cross each other. The sum of the interior angles of a quadrilateral is 360 degrees, as one can see by dissecting the quadrilateral into two triangles using a diagonal. There are several categories of quadrilaterals that are determined by factors such as side length and parallelism and perpendiculars of the sides. Different kinds of quadrilaterals are parallelograms, kites, and trapezoids. A parallelogram is a quadrilateral with two sets of opposite, parallel sides. There are three special kinds of parallelograms: rectangle, square, and rhombus. A rectangle is a parallelogram whose adjacent sides are perpendicular to each other. A rhombus is a parallelogram with all four sides congruent. A square is the combination of the properties of both of these quadrilaterals. It has four congruent sides, and four right angles. The square is the regular polygon for the quadrilaterals.

A kite is a quadrilateral that has two pairs of congruent, adjacent sides. Trapezoids have at least one pair of parallel sides. There are a few specific kinds of trapezoids. The right trapezoid has one side that is perpendicular to the two parallel sides. The resulting adjacent angles formed both measure 90 degrees. (Adjacent describes angles or sides that are next to each other. Opposite angles or sides are across from each other.)

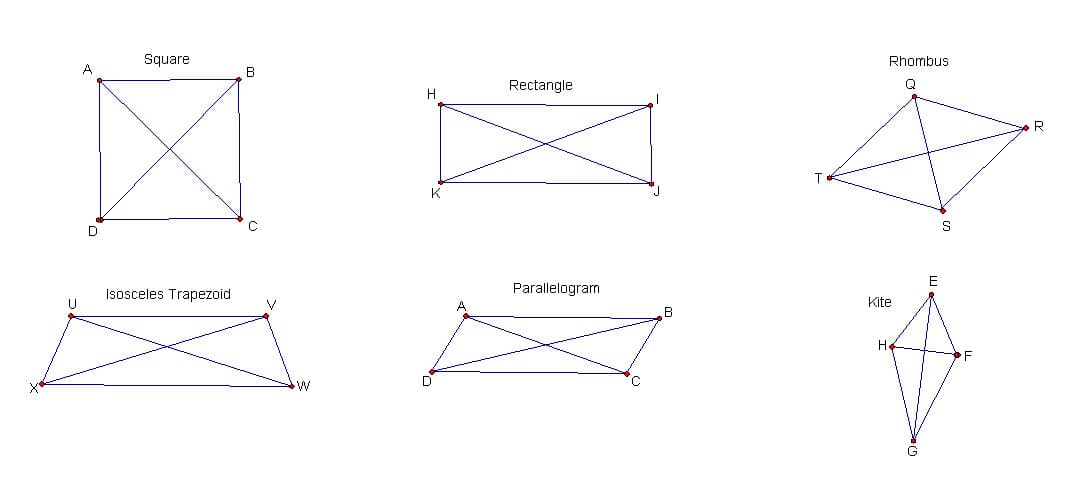

Figure 1.1

Diagonals of Quadrilaterals

A diagonal is the line segment connecting a pair of opposite vertices of the quadrilateral. The diagonals of each of these figures can be used to identify the quadrilateral. When examining diagonals, we can look at how they intersect, as well as if they are congruent to each other. For example, the square has diagonals that are congruent to each other, bisecting (bisect means that they intersect at the midpoint), and perpendicular (they intersect at a 90 degree angle). (see Figure 1.1)

Isometries Within a Figure and Symmetry Classifications of Triangles and Quadrilaterals

Polygons can be transformed within a plane. The kinds of transformations we will discuss are called isometries. "Isometry" means distance preserving: the transform of every line segment by an isometry will have the same length as the original segment. There are two kinds of isometries that can be a symmetry of a bounded figure: rotations and reflections.

A figure has rotational symmetry when it can be rotated around a center point, and match up exactly with itself before it has rotated 360 degrees. If the figure rotates and only matches up with itself at 360 degrees, that is called the identity. When we refer to the other rotational symmetries of the figure, we call those non-trivial symmetries. When students are asked if a figure has rotational symmetry, it is assumed that they are being asked about the non-trivial symmetries.

Reflectional symmetry (otherwise known as "line symmetry") is what students most commonly think of when they hear about symmetry. This is the kind of symmetry in which a side can be reflected over an axis of symmetry to produce the same image on the other side. Essentially, if you could fold an image in half and both sides match exactly, that fold line is an axis of symmetry for the figure.

Figures can have both reflectional and rotational symmetry. In fact, if a figure has two lines of reflectional symmetry, it will also have rotational symmetry. This was something that I never knew, but think that it is important to articulate to my students. By illustrating this relationship, the students can make more connections within the content that they are studying. This can be illustrated by looking at a rectangle. A rectangle has two reflection symmetries, across either of the lines through the center that are parallel to one of the pairs of opposite sides. It also can be rotated 180 degrees to match up with itself. We can also use the equilateral triangle to illustrate this point. This triangle has three reflections, and can be rotated 120 degrees and match up with itself twice.

In geometry, we learn that polygons can be classified using properties like number of sides, length of sides, angle measurement, and diagonals. We have mentioned several examples above of this kind of classification. Triangles and quadrilaterals can also be identified using their symmetries. Not only can we identify a triangle using its symmetries, but also it is specifically defined by its symmetries. For example, if we are looking at a triangle that has only one reflection symmetry and no rotational symmetries, what kind of triangle must we have? We can't have a scalene triangle, because all of the side lengths are different, so none of them would match up if reflected. We can't be looking at an equilateral triangle, because it has rotational symmetry, and three lines of reflection. Therefore, we must have an isosceles triangle. Why does this make sense? Because two sides are equivalent in length, these will be the only sides that when reflected, will mirror each other. Thus there will only be one line of reflection, and no rotational symmetry.

At this point, it may be important to point out that getting used to the idea that the identity as it is considered a symmetry, can take some getting used to. I know that this idea goes against most everything I have been taught about symmetry as a child, and how I learned to teach it to my students. I found that the best explanation of this idea came from Marcus du Sautoy when he had the same curiosities about this property of symmetry and said "But I soon saw that if symmetry meant anything you could do to the triangle that kept it inside its outline, then not touching it at all- or, equivalently, picking it up and putting it back in exactly the same place- was also an action that had to be included." (2)

An equilateral triangle has all equal side lengths and all interior angles congruent, thus it will have three axes of reflection that go through each vertex and the midpoint of the opposite sides. Since this kind of triangle has more than two reflections of symmetry, it will also have rotational symmetry. In this case, it has rotational symmetry every 120 degrees. So, in total every equilateral triangle will have five non-trivial symmetries and the identity, for a total of six. Since a scalene triangle has no equal sides or angles, it won't have any non-trivial symmetry.

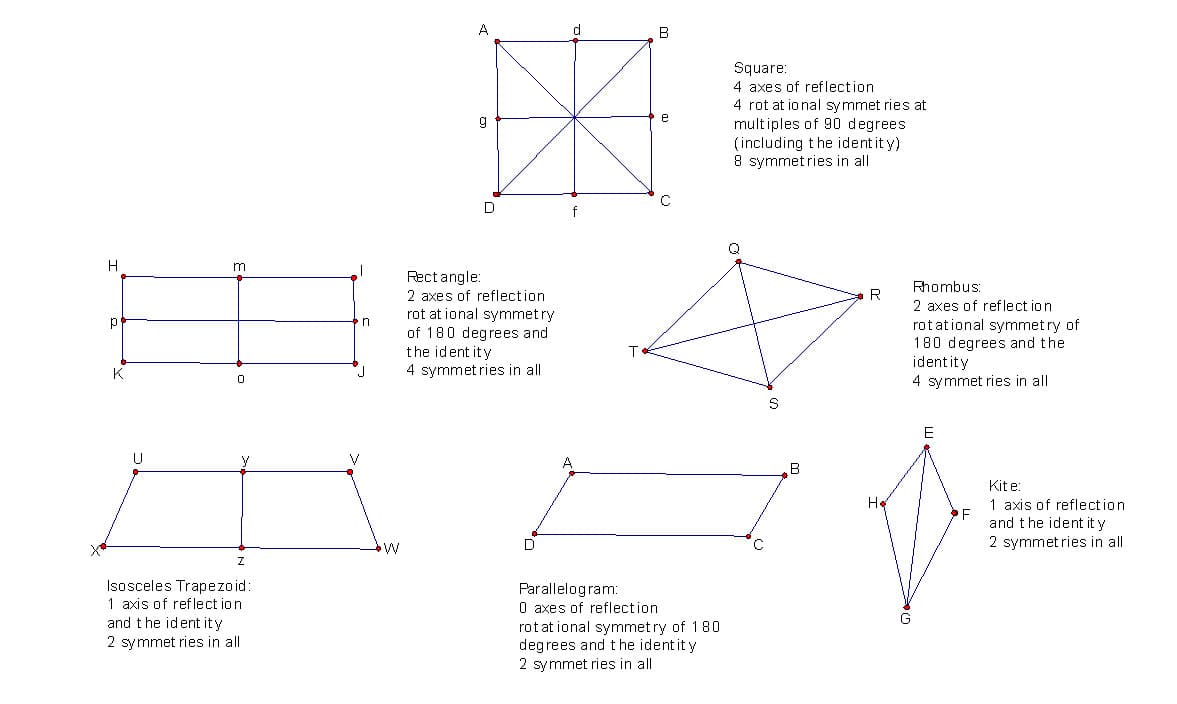

Figure 1.2

Symmetry Classes of Quadrilaterals

Quadrilateral classification can also be determined by the symmetries of the figures. We'll start by explaining the square, since it is the most special kind of quadrilateral. Since a square has four equal sides and angles, it will have reflectional symmetries across four axes. Two of those axes of symmetry travel through opposite vertices. (See Figure 1.2) In square ABCD those axes are labeled line segment AC and line segment BD. The other two axes go through the midpoints of the opposite sides, as illustrated in by line segments bf and ge in square ABCD. Because there are more than two reflectional symmetries, the square must have rotational symmetry. The square has rotational symmetry at 90 degrees, thus there are three non-trivial rotational symmetries. Including the identity, every square will have eight symmetries in all.

The next most symmetric quadrilaterals are the rectangle and the rhombus. Both figures will have two axes of reflectional symmetry. The rectangle's axes go through the midpoints of the opposite sides, while the rhombus' go through the opposite vertices. Please refer to rectangle HIJK and rhombus QRST for a visual representation of these line symmetries. Both of these figures have rotational symmetry at 180 degrees. So, in all each of these figures will have four symmetries, including the identity.

The last three quadrilaterals to classify are the isosceles trapezoid, kite, and the parallelogram (not a square or rectangle). Each of these will have one, non-trivial symmetry, along with the identity, for a total of two. The isosceles trapezoid has one set of non-congruent, parallel sides, and one set of congruent sides that are not parallel to each other. This figure will only have one reflectional line of symmetry across the axis, which runs through the midpoints of the parallel sides, and is perpendicular to them. (See Figure 1.2) This is labeled by the line segment yz in trapezoid UVWX. It will not have any rotational symmetry besides the identity. The typical kite is composed of 2 pairs of adjacent, congruent sides. This figure will have a reflectional symmetry over the axis that travels through the vertices where the congruent sides intersect. (See Figure 1.2) Line segment EG in kite EFGH illustrates this axis of reflection. There will be no rotational symmetry for this figure, except for the identity. Finally, a typical parallelogram will have no reflective symmetry, but will have rotational symmetry at 180 degrees, as well as the identity.

There are a few other things to make note of that will help in proving to that these symmetry classifications hold true. In all the cases that have been described here, if a quadrilateral has symmetries of the type belonging to a given class of quadrilaterals, then it belongs to the class. For one, a 180-degree rotation always takes a line parallel to itself, if the center of rotation lies on the line. This fact can be used to explain the rotational symmetry of parallelograms. The 180-degree rotation of a parallelogram around its center exchanges pairs of opposite sides, and therefore must also exchange opposite vertices. The center of rotation must lie on both diagonals. Since the opposite vertices are exchanged, they must be at equal distance from the center of rotation. The general parallelogram, the rectangle, the rhombus and the square all share this symmetry characteristic. Another thing worth considering is that rotational symmetry will also preserve the diagonals and the intersection point of the two diagonals, around which the figure rotates. If your students study the diagonals of quadrilaterals, then this would be worthwhile for them to consider. Lastly, take into account that a line that reflects to itself through an axis of symmetry must cross that axis at 90 degrees. This is shown in the axes of symmetry that pass through the midpoints of the sides, in the cases of the trapezoid, rectangle, and square.

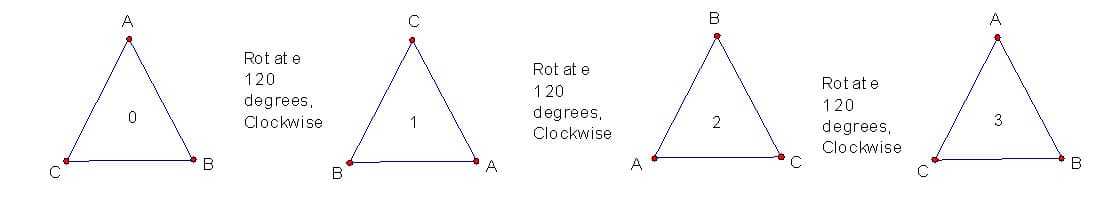

Figure 1.3

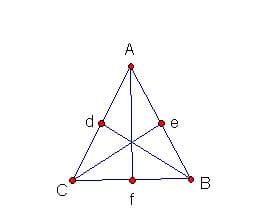

Figure 1.4

If it is difficult to picture these symmetries, do what we would have our students do; draw an example. By drawing an example of the figure you are investigating, and labeling its vertices, you can perform the reflection and rotations to prove to yourself that they are indeed possible. For example, let's take a look at the reflections and rotations in an equilateral triangle.

Figure 1.3 illustrates the rotational symmetry of the equilateral triangle. You can see that as the figure rotates 120 degrees clockwise, the shape and size remains the same. We can see that rotation has occurred because the locations of the points A, B, and C have all changed. Notice that when the original triangle (Triangle 0) is rotated 120 degrees clockwise the vertex labeled A moves to point B. Point B moves to where Point C was, and Point C moves to where A was. Triangle 3 shows the final rotation, which is the figure's identity. Figure 1.4 shows the reflectional symmetry of the equilateral triangle. From every midpoint of a side to the opposite vertex is a line of symmetry.

Isometries of Plane Figures

In the early grades transformations of polygons are most often referred to as "flips, turns, and slides." Again, I believe that it is important for me to recognize that my students will most likely come to me with this prior knowledge of the content without being comfortable using the most formal mathematical language. Thus, it is my job to connect the standard mathematical terms with their prior knowledge, and then be sure to insist that they use the proper terms for these different transformations.

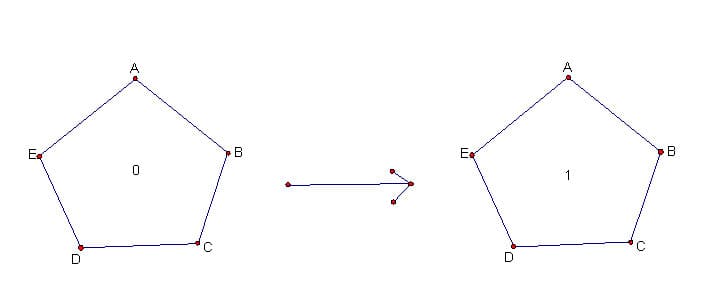

There are four types of isometries that are to be understood as transformations of the whole plane: translations, rotations, reflections, and glide reflections. A translation is commonly known as a "slide" in the early grades. When an object is translated, it moves over a distance while maintaining its original shape and size, and orientation. All isometries preserve shape and size. The special thing about translations is that all lines are moved parallel to themselves, and with the same orientation. To illustrate a translation it may be helpful to label the sides, so that it can be clearly shown that the object has not changed in orientation, but has just moved in a linear path. (see Figure 1.5)

Figure 1.5

Translation

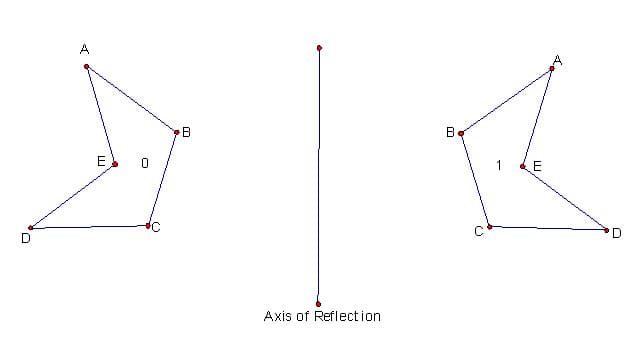

A reflection of a figure is the transformation that produces reflectional symmetry when it preserves the figure. In the early grades this is usually referred to as a "flip." A reflection flips over a line (called the axis of symmetry or line of reflection). The figure will maintain the same size, shape, and angle measurements after this transformation. It can be best illustrated with real world examples such as a picture of a mountain reflected in a lake or other body of water. In a reflection we can identify the line over which the flip was made. This is called the axis of reflection. Each point of the transformed figure will be the same distance from the line of reflection, but on the opposite side. (see Figure 1.6)

Figure 1.6

Reflection

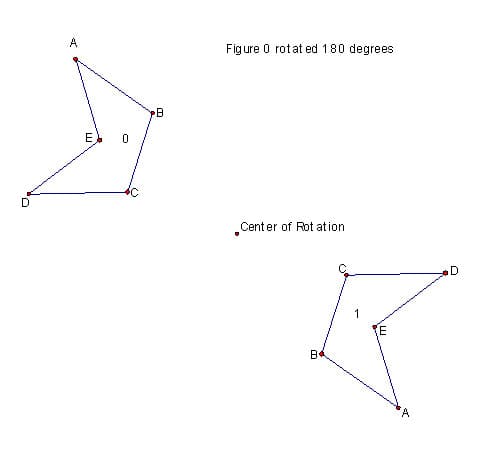

The third transformation covered in the elementary curriculum is what students will call a "turn." These turns are rotations. These are the same rotations that determine a figure's rotational symmetry, but instead of a figure being rotated around its center, it is being rotated around another fixed point and can be rotated through any angle. This point is called the center of rotation. Along with a center of rotation, the figure needs an amount and direction of rotation. Figures can be rotated clockwise or counterclockwise up to 360 degrees. (see Figure 1.7)

Figure 1.7

Rotation

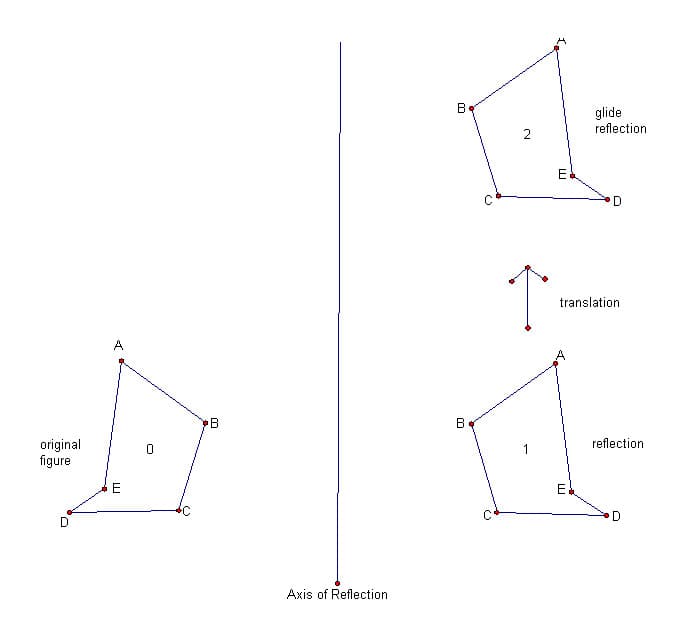

A glide reflection is not usually covered in elementary school curriculum, but since students will be familiar with what it looks like, it is one that I think students would enjoy learning about. A glide reflection is a combination of a translation and a reflection. Since the figure is reflected and then translated, the transformed figure will have the opposite orientation from the original. The best illustration of a glide reflection in real life is a picture of footsteps in the sand. The images of the feet are reflective in nature (as one is a mirror image of the other), and in a natural gait the two footprints will be separated. Each footprint is a glide reflection of the previous one. Glide reflections are also commonly found on decorative borders.

Figure 1.8

Glide Reflection

Some isometries won't change the orientation of the figure. For example, in a rotation, the position of the points on a figure does not change once the transformation has occurred. The same holds true for translations. These kinds of isometries are called direct transformations, or orientation preserving. If the transformation changes the images of the points on the figure, as in a reflection, then this is called an opposite isometry, or orientation reversing. (3)

Comments: