Activities

Changes in a Teddy Graham Population—based on an activity by Bert and Lynn Wartski

Teacher notes: For a class of about 30 students, I will use about 2 boxes of Teddy Grahams. The new mini types will work as well, and will be less expensive. There are actually two types of bears in a box—one kind has their arms raised, the other kind has their arms by their sides. There are almost always more of the arms down bears. I let students work in pairs, and I give each pair an initial population of bears, pouring them from the box onto a clean paper towel at their lab station. I don't count them, because it doesn't matter. Each group starts with about 15-20 bears. Have them count this initial population and record the data. Then tell everyone that the monsters are coming. The monster will eat only three Happy Bears. If there are not three Happy Bears, the difference will be made up by eating Sad Bears. Both partners are not eating! They can take turns, or save all the "eaten" bears until the end and split them up. Then I go around with the second box and pour out a few "baby bears"—about 7-10 in the first few generations until the population gets bigger. I don't count and I don't try to match up the characteristics of the survivor parents with the offspring—it will all work out. Then and only then do the students count the total number and types of survivors plus offspring and record that as generation 2. Each generation count will occur after the monsters have eaten and the bears have reproduced. As the population size increases, I tell them that the monster population has also increased, and by the 4 th and 5 th generations, the monsters are eating up to 6 bears—always eating Happy Bears first if available.

Background Information: If you go out in the woods today, you're sure of a big surprise. If you go out in the woods today, you'd better go in disguise. For every bear that ever there was, will gather there for certain, because today's the day the (Teddy Grahams) have their picnic—(Jimmy Kennedy) Teddy Grahams live in the remote Nabisco Forest of North America. There they roam freely, attending Teddy Graham picnics when they are not hiding from their main predator, the bear-eating monster, Homo horribilis. Teddy Graham bears appear in two different phenotypes. The "Happy Bear" variety often display with their arms raised skyward when startled, freezing into position in an attempt to avoid detection. Apparently they also have very sweet and tender flesh as a result of their more pronounced inactivity. The "Sad Bear" variety never raises their arms, and will run away at the first sight of a bear-eating monster. The rush of adrenaline released by the exertion of their muscles in avoiding capture, results in flesh that is tougher and less sweet. Homo horribilis shows a preference for eating the "Happy Bear" variety of Teddy Grahams if they have a choice. During the course of a year, one Homo horribilis will consume about three Teddy Grahams, and if it cannot find "Happy Bears", they will make up the difference in their diet by making do with "Sad Bears". Teddy Grahams breed once a year and a new crop of bear cubs are produced shortly thereafter. (It has not been confirmed, but it is believed that is the purpose of the "picnics".)

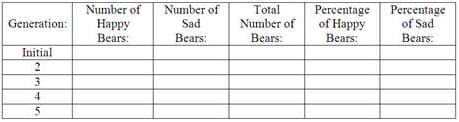

Assignment: Observe the population of Teddy Graham bears in your section of the Nabisco Forest for 5 generations and make note of the total population size initially and at the end of each breeding season. Also record the breakdown in the population of "Happy" and "Sad" phenotypes for each generation.

Results:

Analysis of Data:

- Construct a graph showing the change in the percentage of Happy and Sad bears in each generation.

- Which variation in the Teddy Graham population was least favorable in terms of survival?

- How did this affect the population over time?

Conclusion:

- At times there may be no surviving Happy Bears during the mating season, and yet there will almost always be some Happy Bear cubs born each year. How can this be explained?

- Will the Happy Bear trait ever disappear from this population? Why or why not?

- Did this population of bears change over time, and if so, what caused it to change, and in what way is the population different now?

- How might the change in the population of Teddy Grahams affect the Homo horribilis population? In what ways might that population start to change over time?

- What would happen if the Happy Bear trait became more favorable in this environment?

- What might happen if it were favorable to be heterozygous rather than homozygous dominant or recessive?

After a discussion of Charles Darwin's theory of Natural Selection, students will relate the results of this activity to the main points of the theory, recording it in their Biology Journals:

- There is variation in a population….(ex. There was variation in the traits of the Teddy Grahams. Some were easier for the monsters to catch.)

- More offspring are born than will survive

- There is competition for limited resources

- Those born with favorable variations will get the limited resources, survive, reproduce and pass on those favorable variations.

- Favorable variations accumulate in a population over time, changing the population.

With some classes, I might go further and have them calculate the frequencies of the alleles:

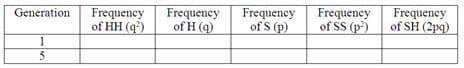

Analysis #2—The Hardy Weinberg Equation

Sexual reproduction shuffles genes in each generation so that the frequency of phenotypes is not always the most reliable way to measure whether or not certain alleles are being selected against. But it is also impossible to look at an individual with a dominant phenotype and determine whether it is homozygous dominant with two dominant alleles, or heterozygous, with a dominant and a recessive allele. The Hardy-Weinberg equation provides a statistically reliable way to estimate the frequencies of two alleles for a trait. If a population is at equilibrium and is not evolving, then the frequencies of the alleles should stay the same over time.

If the frequency of the allele S for the Sad trait is p and the frequency of the allele H for the Happy trait is q, then all the alleles for this trait in a population would be p + q=1. If some bears are homozygous for Sad then the frequency of that phenotype would be p 2. The frequency of homozygous Happy bears would be q 2. There would be two ways to get heterozygotes—pq or qp, so the frequency of heterozygotes is 2pq. Adding up the frequencies of the alleles for all possible phenotypes, you would have:

p 2 + 2pq + q 2 = 1.0

p + q=1.0

p 2=SS

2pq=SH

q 2=HH

If the Happy allele is recessive, then we can look at the percentage of Happy Bears in each generation and determine q 2. For example if the percentage of Happy Bears is 9% or 0.09, then q 2 = 0.09. Now solving for q—the frequency of the H allele would be 0.3, and if q is 0.3, then 1-q=p, so p, the frequency of S, is 0.7

1. Use your data to solve for the values of the Happy and Sad alleles in the initial population and in the 5 th generation. If they frequency of the alleles has changed, then the population has evolved—did it?

2. How could you determine the rate at which the population has evolved?

The Mystery Trait

Teacher Notes: This activity is similar to the Advanced Placement Biology Population Genetics and Evolution Lab #8 that uses cards with alleles written on them that students use to represent their genotype. I will bring in a small wading pool to represent the "gene pool" of our population, and a trash can labeled "Evolutionary Trash Heap". Half of the cards will have "H" and half will have "h" to represent the dominant and recessive alleles for normal hemoglobin and the sickle cell version of hemoglobin. After the initial count of genotypes, students who are hh will "die" as well as a few who are HH.

Background Information: Evolution is defined as a change in the frequencies of alleles in a population over many generations. A population's gene pool is the total of all the alleles carried by all the individuals in that population. Because sexual reproduction shuffles alleles in each generation, the result is often a change in the frequencies of various phenotypes in the next generation, without necessarily a change in the frequency of each allele. But what happens if certain phenotypes are selected against? Would this change the frequency of one allele or the other? Complete the following hypothesis about the effects on a population's gene pool:

Hypothesis: If one phenotype is selected against in a population, then …

In this activity, the dominant alleles for a trait will be represented by the letter H and the recessive allele by the letter h. Possible genotypes could thus be ______________, ____________, or _______________.

Procedure:

Note: It is important that during this activity, all students listen carefully when we are collecting the tallies of genotypes from each generation for our class data.

- Each student will be given two "allele" cards from the class gene pool—and H and an h—so that everyone starts out as heterozygous genotypes.

- To represent reproduction, each student will then pair up with another student. Holding the cards behind your back so that you do not know which card is which, you will hold out one of your cards—your gamete—to your partner. These two cards represent one offspring. One person now takes on the genotype of the offspring, getting additional cards from the gene pool as necessary.

- Selection now occurs…

- individuals do not "survive", they will throw their cards into the Evolutionary Trash Heap (ETH) bucket and they sit out until they can take on the offspring's cards of two surviving parents. The teacher will conduct a count of each surviving student's genotype, HH, Hh, or hh, using hand counts and record the class tally on the board as generation 2.

- Students pair up with someone else and steps two and three are repeated. If the offspring and both parents survive, a student who does not have cards will take on the offspring's genotype. Listen for the count! The new offspring and the remaining parents will represent the next generation.

- We will continue this for several generations. At the end, copy the class data from the board into your journal, and answer the following questions in your journal:

Analysis of Data:

- What might have been the favorable variation in this environment?

- What was the favorable variation?

- Explain the continued appearance of the unfavorable variation being born in the population, even though it does not survive.

Justine Busto

October 24, 2010 at 12:11 pmSurvival of the Fittest? Evolution and Human Health

Very interesting Unit! I don't teach Biology, but that was one of my favorite subjects in high school. I'm glad to know that there are teachers who can get outside the box of the standard curriculum and make ideas and concepts interesting and applicable to students' lives. Bravo Connie!

Comments: