My curriculum unit, Diverse Journeys – Americans All! will allow students to grasp the complex concept of being a United States citizen via birthright or through the naturalization process. Students will:

- speculate about and subsequently define what it is to be an American;

- explore different ways diverse people arrived to American shores bringing with them varied cultures and traditions;

- define the terms "immigration" and "naturalization";

- evaluate whether in the past all inhabitants within America's shores arrived via immigration, and if not, to debate whether those who did not immigrate should be considered American;

- define the rights and responsibilities of United States citizens today; and

- based on their own terms, realities, and courses of study, delineate what it means to be American.

By way of student-generated inquiry, family interviews, research projects, viewed films and subsequent story creations shared with the school community, young researchers will gain a deep understanding of American citizenship. Using select non-fictional and realistic fiction resources, young learners will strengthen reading and reading comprehension skills, synthesizing important information to make text-to-world connections, thus deepening their understanding of the subject at hand. Most important, students will come to recognize that irrespective of the journey, diverse groups of people born or naturalized in the United States constitute the American mosaic.

Through its implementation, it is hoped that Diverse Journeys-Americans All! will encourage students to embrace diversity and the unique contributions made by diverse cultures to American society.

Getting Started – Establishing the Tone

During first six weeks of the school year, I set the tone to create an engaging, culturally-inclusive classroom environment. I make every effort to collect and have on hand a wide selection of reading materials. These children's book resources—written across genre and abilities levels—reflect the represented cultures within our school and my specific classroom population. To the best of my ability, I canvass these materials to identify biased or stereotypical wording. I check the copyright date: if resources pre-date the early 70s, I place them to the side or strategically consider how to use these materials to counter misconceptions, as children's books created before this period often contain stereotypical concepts and/or images. I also make it a point to familiarize myself with the customs and mores of key cultures represented in my class. I want to ensure that when my students and their parents set foot in our learning space, they come to realize it is a classroom environment that embraces all. I make it a point to make use of key words of welcome when I meet and greet my students: Ni hao, hola, koninchiwa, kedu, an-nyong hasao, shalom, namaste, wo ho te sen, bon jour, olá, guten tag.... Needless to say, my use of salutations in diverse languages has significantly expanded. In time, however, my students come to understand and make use of these convivial greetings as well. In this way, the door to embracing one another as a microcosm of the American community is opened.

Defining Moments

Within the first week of school, our class jumps right into determining what it means to live and work in a classroom community and to be a classroom citizen. We define the term "community" and collectively decide that it is a group of people who live, work, and/or are situated in the same region. We too define "citizen" and establish that the word refers to one who is a permanent resident and rightfully resides in a country because he or she was either born or legally accepted within a designated community. The children soon agree that they are citizens within our classroom community because they were born in America and legally have a right to be in our school and our classroom.

Having established this foundation, I ask, "Do you think citizens have any special role to play within a given community? Do you have a role to play in our classroom community?" I give the children a few minutes to gather in small groups to brainstorm. Shortly thereafter, my children agree that classroom citizens need to establish class rules that include academic and behavioral standards. They additionally agree that classroom citizens should know, embrace, and strive to follow rules. (My third graders are a tough bunch: they often assert that the consequences for not doing so should be etched in stone—unless THEY have perpetrated the infraction).

We continue our discussion and subsequently create a Classroom Compact, a collaboratively agreed upon listing of do's and don'ts that coincide with our school's overall academic and behavioral philosophy. The children create and sing songs that embrace those rules. We take it a step further: to get a feel for the writing ability and oral communication skills of my young learners, I introduce a writing exercise to have them think about and record academic and behavioral expectations for themselves as being third graders. With pencil and paper in hand, each child creates a biographic snapshot. Upon completion of the first draft, each child is given the opportunity to share their work with one another. Onlookers listen attentively as each peer reads aloud to spotlight themselves and the positive behavior and social interaction they intend to live out in our classroom, deepening our relationship and understanding of one another.

By the end of the first week, my students understand that ours is a classroom community filled with diversity. We move on into broadening that concept. As part of our introduction to Social Studies, we sing and revisit the words to several patriotic songs (e.g., America, My Country 'Tis of Thee, The Star Spangled Banner...) and know each word in the Pledge of Allegiance. Although many of my students can belt out the melodies and have memorized the wording, they have not delved into the significance of their meaning. Using oversized chart paper, we list key vocabulary imbedded within each selection (e.g., allegiance, indivisible, justice, liberty, nation, pledge, pilgrim, republic...) to determine their meaning and ultimately embrace their significance.

Through these strategically planned interactions, my students sense that they are all citizens and an integral part of our classroom community. The children catch on, noting that the classroom is like a miniature world. I introduce the term "microcosm" and reinforce that we can consider ourselves a microcosm of our nation. Diverse groups of people—Americans all.

A Major Question Posed

The meaning of being a classroom citizen having been established, we broaden our scope: "Are you an American citizen? If so, how do you know?" Once again, I disperse my students into small groups and provide an opportunity for them to brainstorm and share their conjectures. Hands raised, they eagerly and almost unanimously clamor, "BECAUSE WE WERE BORN IN THIS COUNTRY!" I share that although this reality holds true for many like themselves, not everyone is born in the United States. Those who are not born here must undergo a particular process to become a citizen. Thus, the door is opened for our learning adventure to begin.

Provide Background Info

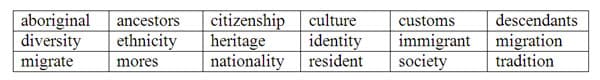

Before introducing supportive, historical background information, assess what the children already know by using a K-W-L chart. Generally ask them to define what it means to be American. Record student responses on oversized chart paper for future reference and review purposes. Subsequently, familiarize students with key terms they will encounter in their course of study:

Note that specific terms such as race, ethnicity, nationality, customs, mores, nationality, and tradition can prove complex and theoretical for young learners. Clarify these definitions through the use of open-ended discussion, role play, and related activities. In time, students will learn to understand these concepts. For starters, however, emphasize that race is a categorization of people into large, distinct groupings based on geographic ancestry, physical characteristics coupled with different and/or similar biological traits. Race is usually classified in color-coded ways, i.e., black, red, yellow, brown, white, respectively representing people of African descent, aboriginal American, Asian, Latino/Hispanic, and people of European ancestry. Highlight that ethnicity implies people identify with one another based on a shared, common heritage, language, or religion (like when we see specific ethnic groups convene to participate in culturally specific festivals and parades). Idealistically, nationality implies that an individual belongs to a nation that shares a common ethnic, language, and cultural identity. (The United States is a complex nation in that it is a heterogeneous society in which not all citizens claim to share a common lineage.)

Culture represents behaviors and beliefs indicative of a particular social, ethnic, or age group (like sitting at a dinner table and waiting for the elder in the family to say grace before the family begins the meal). Customs represent traditional practices embraced by groups of people in a particular way (like celebrating Christmas, Hanukkah, Eid, or Kwanzaa), and mores signify the habitual practices and moral values they accept and follow (like being mindful of elders or nurturing children in one's family and community).

Additionally, clarify the terms "emigrant," that implies an individual has departed from his or her original homeland to settle in a new country or region) and "immigrant," that connotes an individual has come to a new country seeking permanent residency. By introducing such terminology, we empower young learners to enhance vocabulary and make text-to-self-to-world connections as the implemented unit progresses.

Gathering Info/Digging Deep

To rouse curiosity, inform your students that they are about to undertake a grand adventure into the past. To achieve this end, they will stand in the shoes of a researcher, except that they will delve into historical and realistic fiction literature to conduct their exploration.

Introduce the world map. Review its purpose and technical aspects, highlighting directionality and territorial classifications. Point out continental land masses and introduce geographic terminology. Emphasize that somewhere in our genealogy, many of us are the descendants of people who once hailed from one or more of these represented lands. Europeans came from Europe; African peoples were dispersed from Africa, aboriginal Americans resided in both North and South America. Asia, the largest continent, spans from what we today all the Middle East through the Philippine isles; diverse groups of Asiatic people hail from this region. The Aborigines, the original inhabitants of Australia, and others from as far as Europe and Asia, reside on this, the smallest continent.

Follow up by sharing that America is a unique land in that people from diverse cultures live within its shores. Sundry people... Hopeful, thriving, laboring people... Generations of people who in some way contributed to the growth of this nation. The "splash-of-seasoning-accompaniment" we affix to the label American (i.e., African-American, Italian-American, Haitian-American Irish-American, Korean-American, and the list goes on) is reflective of that human montage. But who and what does it mean to be American?

Emphasize that when we retrace our country's history, we soon recognize that the diversity phenomena found within the United States began centuries ago. We too learn that not all of our country's residents immigrated to this new land—that the nomenclature "American" takes on new significance when the story told is culturally inclusive.

The First Americans

History and contemporary Science reveal that aboriginal populations—who have been disrespectfully and generally labeled red-skinned people and/or Native Americans—migrated to what we refer to as the Americas in three major waves as early as 12,000 years ago. Over the centuries, they spread throughout North, Central, and South America, adapting well to their environment. Those who settled in what today is known as the North American continent flourished, embracing diverse lifestyles based on the terrain on which they resided. For example, during the 14th century, northwestern coastal people had developed hunting communities; elk, deer, antelope, beavers, rabbits, and rodent were favored prey used as sources of food, clothing, utilitarian objects, and shelter. Adept in fishing, they were masters of catching salmon that traveled upstream. They dwelled in major villages situated along the coastline. Houses accommodated extended families, and a social order was well-established. The indigenous inhabitants of the Great Plains region mastered planting maize and hunting bison. A migratory group, they worked as one with the land, hunting, planting, and gathering seed in a cyclical fashion. 1 As late as the 17th century, flourishing aboriginal communities existed on the northeastern shores. For example, when Europeans landed in the regions we today call Virginia and New England, adept indigenous peoples had already established a thriving culture and communities and resided therein. 2 Ultimately, Native American people inhabited North American shores long before the arrival of European explorers and settlers.

The Arrival of Blackfolk – A Clarification

The first blacks to set foot on American soil were not all enslaved Africans. Some were members of seafaring crews. Jan Rodrigues, a black sailor and free black man for example, arrived on Manhattan Island in 1613, six years before the first group of slaves were brought to the Jamestown Colony. Some worked as indentured servants, residing under the same grueling living and work conditions as indentured whites. Around 1634, Mathias de Sousa, another individual of African descent, labored as an indentured servant. After having worked for four years in this capacity, he was granted his freedom. A freeman, de Sousa enjoyed the rights and responsibilities held by white counterparts. This free black man was among the original black settlers in what we today call Maryland. 3 Thus, although a vast majority of Africans brought to the New World were enslaved, it is a misconception to believe that all African people brought to America were in bondage.

It is also a misconceived notion that the importation of Blacks to the Americas was rooted in the Jamestown colony in the North American south. In fact, the overall enslavement of black people in the Americas began in the pacific coastal regions of South America in what we today call Columbia and Peru. (During the mid-1500s, Spanish slave traders used Africans and aboriginal Americans to mine silver in Peru. Other blacks were transported to Mexican mines. By 1570, African slaves were brought to Brazil by Portuguese slave traders, forced to cultivate revenue producing sugar plantations. During the 1600s, Spanish, French, Dutch, and Portuguese colonizers used black laborers in the cultivation of sugar and tobacco plantations, producing unimaginable empires for these European nations.)

The African slave trade was a full century old before the trade began in what we today call the United States. In 1619, twenty Angolans were brought to the Jamestown colony. Eight years later, the Dutch West India Company delivered the first load of Angolans to New Amsterdam—today known as New York City. Enslaved blacks were used to clear land, cut timber, build houses, plant crops, and ultimately produce empires for white businessmen. Black human cargo was brought to the American colony as a result of a struggle between the English, Dutch, and Portugal for the control of the lucrative trade. By 1697, the Dutch began bringing slaves directly from Africa to the Americas; like coveted consumer products, blacks were imported across the Atlantic to boost sales and the "new American economy". 4

Incredibly, 12.5 million Africans were shipped to the New World between 1501 and 1866. Fifteen per cent died in the Middle Passage, the dehumanizing slave ship route across the Atlantic Ocean, between Africa and the shores of the Americas. More than approximately 11 million Africans survived the odious journey. Fewer than half a million—i.e., 450,000 blacks shipped from Africa to the U.S. during the trans-Atlantic slave trade—were held in bondage within the United States. In this new homeland, blacks from across the Africa Diaspora were sold and forced to labor in coffee, tobacco, cocoa, cotton and sugar plantations, gold and silver mines, and rice fields. They worked in the construction industry, building homes and cutting timber for ships. They built housing for the master and others. They labored as house servants and were bred for future economic gain. 5 Although they now dwelled in America, people of African descent did not reap the fruits of liberty in this Land of the Free.

The First Processing Center?

The slave trade increased tremendously in the colonies during the 17th and 18th centuries. Blacks were brought into the United States not only to tend the fields harvesting cotton and tobacco, but to cultivate rice plantations in the South Carolinian region. Between the early 1700s through 1799, Charleston, South Carolina, became one of the major slave ports in North America. Many blacks brought into this locale hailed from rice-growing communities like the Senegambias. Their agrarian abilities proved advantageous for southern landowners, further enhancing the lucrative trade of human cargo. 6

Many slave ships that arrived to North America first took port on Sullivan's Island, a barrier isle on the north side of Charleston Harbor. At this South Carolinian site, passengers and crewmembers were held in quarantine, detained either aboard the slave vessel or on board the island from as long as ten to forty days. Crew members and the enslaved alike were scrutinized because the sailing vessels that housed them were often wrecked with infectious diseases like cholera, smallpox, and measles. In time, healthy passengers were released, with able-bodied blacks being processed and sold to fulfill the needs of supply and demand. Ironically, African people had been isolated, examined, and screened before being able to set foot on American soil, a process that would be experienced by countless numbers of immigrant newcomers in future decades. Thus, Sullivan's Island served as a processing center for "African newcomers;" the only exception is that these new arrivals came not of their own volition, but rather as shackled merchandise sold to the highest bidder. 7

European Immigration

In the early North American English colonies, countless numbers of immigrants set out from European shores to flee religious and/or political persecution. Some who had already settled in the American colonies needed workers to help cultivate the land. They offered incentives to bring in white indentured servants to fill this need. Many trustworthy and diligent laborers were hired. Oftentimes, they were duped into working as tradesmen in a new land for established periods of time, after which they would be given parcels of land. Many convicts were brought over from Britain; thieves, thugs, robbers, and rapists were among those sent to labor in the American colonies.

Many who came over between the sixteen and seventeen hundreds risked their lives to leave homelands wrought with poverty and crime; upon arriving in the early American colonies, as in Jamestown and Maryland plantations, many European immigrants worked under deplorable conditions as indentured servants. 8 Between 1760 through 1775, waves from the British Isles flooded North America. Protestant Irish, Scots, Swiss, and German-speaking immigrants stretched across the New England region, spreading out to Pennsylvania down towards Virginia and beyond. With the influx of diverse European groups came differences in religious practices and social status. The need for colonial labor, however, often outweighed those differences. As a result, established British settlers tended to ignore differences among particular groups of European newcomers, and many European immigrants found America to be more tolerable than their original homelands. 9

Between the early-to-mid-1800s through the 1920s, 23 million immigrants had sailed across the Atlantic, crammed in huge sailing vessels with the hopes of residing in the United States. Many traveled from southern and eastern Europe fleeing everything from famine and homelessness to economic woes. Some were exiled for having committed crimes in their homeland. Huge numbers, in search of a new land where a better way of life was deemed possible, stepped out on faith to make the journey. Between the 1930s to mid-60s, the influx of immigrants remained constant. Millions of people continued to come to America's shores. Some came of their own choice in search of beginning new lives; others came to escape the aftermath of war, slavery, political persecution, and famine. 10

Restrictive Surprises

Before the 1800s, it seems there were no limitations on the influx of newcomers to what we today call America. By the early-to-mid 1800s, widespread fear began to set in. Ironically, some people who had already gained citizenship status within our country took on a different view. They observed that communities were rapidly growing, some with residents unlike themselves. They held that many newcomers were impoverished and uneducated. Communities were becoming overcrowded. Living conditions for many were deplorable, and competition for employment was fierce. Because of these societal realities, many former settlers believed the government should limit the number of immigrants seeking entry and citizenship into our country.

For example, during the late 1840s, Roman Catholic Irish arrived in growing numbers. To many native-born Americans, impoverished Irishmen were inundating the cities' poor houses and asylums, having a negative impact on the economy. These points-of-view were not limited to the Irish alone. The Chinese had heavily immigrated to the West Coast during the Gold Rush era, between 1849 and 1862. Like many European immigrants who had previously settled in the region, many Chinese were in search of a better life and economic opportunities. Adept workers, they were used as a source of cheap labor in helping to build the transcontinental railroad. Working at lower wages proved problematic for many whites. Additionally, the countenance of the Chinese differed significantly from their Irish, German, and British counterparts. Repeatedly at the brunt end of racial slurs, they were often targeted because of their physical appearance. In time, Chinese immigration was banned; restrictive measures were set in place beginning with the Chinese Exclusion Act. 11

The Chinese Exclusion Act was passed into law by the U.S. Congress and signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882. The Chinese Exclusion Act was the first significant law that restricted immigration of a specific ethnic group into the United States. Although not overtly asserted, it can be deduced that race and ethnicity served as a contributing factor in the government's enacting this legislation. Interestingly, this Act proved a restrictive measure not only to the Chinese. It restricted working-class ethnic groups from immigrating to the United States: those newcomers included the Japanese, Filipinos, and myriad individuals hailing from Asian nations.

In response to increasing public opinion, Congress continued to create laws that limited the number of immigrants who could enter the United States from any particular nation. One of those laws was the Quota Act of 1921; it drastically impacted the admission of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe to our country. Additional quotas were enacted by the government: in 1924, laws were passed to counter the influx of massive immigration by Italians, Poles, Hungarians, and other European immigrants. They, too, were discriminatory in nature in that they were established based on the individual's national, religious, and ethnic background. Supposedly, immigration quotas correlated with race and ethnicity were revised and abolished in 1965. Immigration, however, continues to be a major political debate in the 21st century. 12

Processing Centers, Too!

By January 1, 1892, Ellis Island was established and served as the primary immigrant processing center for our nation. From 1892 through 1954, more than 12 million immigrants were processed through this port of entry. New arrivals underwent intense questioning and examination within the facility before being allowed to enter the country; this process was labeled naturalization. Many immigrants referred to Ellis Island as "Heartbreak Island" because of the dehumanizing interrogation processes experienced to be eligible to become an American citizen.

Similar "holding pens" existed along the west coast of America: Angel Island, a triangular land mass located in San Francisco Bay, California, was one of those sites. In 1910, legislation was passed to use it as an immigration processing site for the anticipated influx of European newcomers with based on the threat of World War I. The expected European surge never occurred; instead, a flood of Asian immigrants ensued. 13 The United States did not have a secure way of identifying or confirming whether newcomers were related to Chinese Americans who already resided in the U.S. As a "precautionary measure," immigrants were forced to reside on Angel Island for up to six weeks with no guarantee of entry. Families housed therein were isolated and incurred deplorable conditions. They never expected their dream of America to take such an unexpected turn.

It is hard to believe that many of us—descendants of these diverse cultures—reside in the United States today because of past ancestral journeys, but it is true. In time, newcomers became residents and residents became generations of diverse families born in America.

Comments: