A Middle: Analogy : Simile :: Metaphor : Simile, or "a beautiful day of sunshine" 55

So, what are inferences and what is intuition? Well, I have a theory, my pet theory, and I will give it a name, the Similes, and I will give it wings in hope that it successfully flies with Icarus's enthusiasm but more importantly with the late wisdom he gained while falling.

First a definition of the literary kind: Simile is "a figure of speech involving the comparison of one thing with another thing of a different kind, used to make a description more emphatic or vivid (e.g., as brave as a lion, crazy like a fox)." 56 Let me clarify: Similes are structured like analogy in that they compare concepts, often in terms of "is like," but they are of the mind of metaphor in that they compare unlike things. They are both is and like, and although other words and phrases create literary similes, they all contain the essences of is and like, as with crazy like a fox, above, where 'is' is implicit in the adjective crazy if not directly stated before. Here is further clarification of these three modes of thinking with sample sentences (all similarly structured for clarity):

- Analogy (two concrete or abstract but similar things, which are then likened one to the other): (1) A book, like a short story, is worth reading. (2) Love and kindness alike are fueled by passion.

- Simile (one concrete or abstract thing, which is then likened to an unlike concrete or abstract thing): (1) The book is like an angel's dream. (2) The mind is like a brilliant illusion.

- Metaphor (one concrete or abstract thing identified as another unlike concrete or abstract thing): (1) The book is an angel's dream. (2) Truth is an elusive tiger.

And, finally, here is my pet theory set in flight: similes are the interpreters between analogy and metaphor, the sparks between synapses, the space between the finger of Adam and the finger of God (Michelangelo), the flow between women (X:X, analogy) and men (X:Y, metaphor), between languages and cultures and peoples and people, between fire and water (Icarus) and hubris and despair (Narcissus/Echo), and between the infinite imbalances that we all are mutually and continually shifting and turning and humming between in pursuit of balance. They are spirit that breathes, and though they might be invisible and gather like dark matter, they also radiate like pure light and pull like dark energy, and they are like the Sun as analogy equals Earth and metaphor is the Moon. In them, their beauty, "all is made whole… all is restored." 57

Reality check: I was taking a liberty with the wings of my imagination and dreams, and thus admit my pet theory is extravagant (though I can see correlations everywhere); yet I stand by my insistence that simile is the go-between for analogy and metaphor, and emphatically believe that this framework is the key to meaningful interpretation and understanding of any text. In interpretation, similes help the mind build analogy towards metaphor but also reduce metaphor to basic analogy.

So, without further ado, except for a succinct introduction and description of fourfold reading, or Pardes as it was taught to me by a visitor to the seminar, it is time to make an invisible thread visible, one that weaves through literature and life, particularly the literature for this curriculum. 58 I present it in the form of narrative, a sort of riff, that elucidates the ideas and concepts that string the invisible thread of the literature for this curriculum. I will also do so having interpreted them through fourfold reading. That means that I read literally first, metaphorically second, understanding that they are not what they are but something else, analogously third, asking how they apply to me personally (just as each person does the same, personally), and fourthly for the revelational, that is, seeking personal revelations:

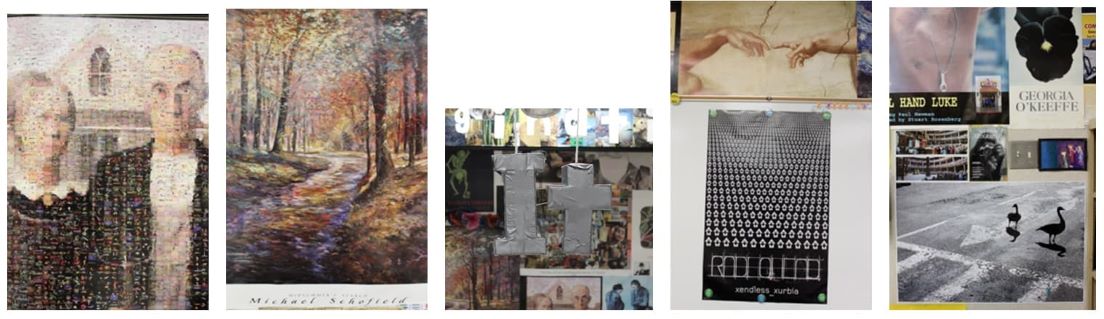

The poster Photomosaic of Grant Wood's American Gothic is quite literally comprised of hundreds of tiny photographs of natural and man-made items that, taken as a composite image, evoke an image of the original painting. So, though the image is not actually there, we cannot help but see it. This is true with literature and life, too. Michael Schofield's Midsummer Search similarly 'reveals,' through composite colored paints and brushstrokes (via the poster medium of ink on paper), a dirt road within woods that bends to the left and into the future (notice the conceptual shift between direction and time). Metaphorically and conceptually, the picture represents infinite possibilities such as danger in the depths of the woods, light and understanding ahead, mystery in the bend of the road and in time, etc. Juxtaposing these images with Michelangelo's, we realize that spaces, or lacunas, allow infinite perceptions and ways of being, but especially, in context of this curriculum, the feeling of loss and the potential to regain identity.

The Radiohead poster confronts the indifference of sameness that systems and people put upon each other, and the image itself is akin to the iconic Malvina Reynolds song, Little Boxes, that are made of "ticky-tacky"—which are the very houses many of my students and their families reside in. 59 The stark difference is that the poster is filled with hundreds of white houses with upside-down black houses (otherwise identical) within them. They are devoid of color, devoid of grayness. Little Boxes, though, confronts the same evil even though the houses it condemns are multi-colored. It is the conformity and the willingness of people to conform that Reynolds indicts. My photograph of two geese, Gray Matters, speaks to, among other things, the choice of following others or finding one's own way (though not alone or to spite others).

Unfolding Bud is a beautiful and accessible poem about reading poems that models its message by means of its metaphor: a flower bud takes time and nourishment to open. And what one finds in them is no different from the miracle of seeing American Gothic or understanding the power of the space between fingertips reaching to regain identity to be one with God. To Look at Anything also models its message, too, which is about having patience and passion for discovering miracles and beauty. Fifteen captures that moment of realizing the infinite in the moment, especially as it speaks to a teenaged boy's discovery of the power of life. What he literally discovers is a motorcycle flipped over on the side of the road with the motor humming. Through his investigation of the scene (or it could be a poem) he discovers life, and friendship, and the power in being. It ends with him looking down the road of life, similar to the goose that appears to be seeing the open road (of course it's only personification – a kind of metaphor).

Grisha, an amazing short story about the most amazing day in the life of Grisha, a toddler who goes with his 'Nursie' to his first parade, reveals how children perceive the world (such as with object permanence 60) via associations through analogy and metaphor, but also misperceive, all while learning the illogical reasoning (to him) of adults as they punish him, time and again, despite his brand new experiences. The ending is most meaningful as it demonstrates how we at times misinterpret and assume, and ultimately force out meaningful experiences by 'medicating' children and, thus, metaphorically flush out all they have learned. Addressing the other spectrum in childhood, the transformation into adulthood and disillusion, No One's A Mystery magically reveals how teenagers have amazing intelligence, but unfortunately their narrow vision and focus on ungolden things keep them from seeing the bigger picture that healthy relationships afford. The narrator relates her experience with Jack, who for her eighteenth birthday gives her a "five-year diary with a latch and little key, light as a dime." What ensues is a debate on predictions of what she will write in her diary, but what the story makes evident is teenagers' romantic and idealistic hearts and minds that keep them from seeing the obvious. Fortunately for the narrator, when she brushes off the dust on her derrière she sees the dust in the shape of a butterfly, suggesting… well, just consider what butterflies emerge from. Salvation speaks to the pressure of conformity under religious expectations. It is rife with irony, and Hughes's voice is as authentic as its message is universal: What good is religion if it destroys faith? Or, put another way, what good is schooling if it destroys inquiry and passion?

Fahrenheit 451 is Plato's "The Allegory of the Den" manifested in characters who choose to seek life and light, or not, while struggling to adjust to seeing and perceiving or easing into blindness and death. In the process, mistakes are made and disasters unfold. The novel and the allegory both serve to remind us of our limited insights, foolish beliefs and misguided steps to action. As for the last, The Catcher in the Rye, it is an indictment of schools and people who claim to be there for kids but, in fact, fail to be, over and over and over. Is Holden Caulfield a whiner and complainer? You can decide for yourself, for no one truly is a mystery, but the point is not to indict him but to save him, and I prefer to save him. He is, after all, lost in that middle ground of teen-dom between adolescence and adulthood without a true friend. He asks in the form of a dismissive statement, while resting in a 'hospital' for the 'ill,' still hopeful though full of doubt, "if you really want to know about it…." Well, do you? He wants to know, as you, after all, are suffering there with him, in your own delusions, as his roommate!

"The goal of education is to make up for the shortcomings in our instinctive ways of thinking about the physical and social world," says Steven Pinker in the closing chapter, "Escaping the Cave," of The Stuff of Thought. "And education is likely to succeed not by trying to implant abstract statements in empty minds but by taking the mental modes that are our standard equipment, applying them to new subjects in selective analogies, and assembling them into new and more sophisticated combinations." 61 That, I say, is spoken in the voice of simile, and it makes me smile as a smile is like the sanctity of simile.

Now, if these theories are true, then we have to change, and I believe it is through being like similes that we will be able to see eye to eye, being flexible in translating abstractions to be the go-between and the breathing of spirit, person to person, animal to animal—and plant—elder to child and child to elder, as well in all other ways of being, regardless of, well, anything. I suggest a meaningful and healthy way for change is through literature that directs our perceptions towards inanimate Its and that speaks to deepest truths, whatever they may be, and so I offer three texts as a starting point. Even though they were written by three people who have never met, they are nevertheless of the same spirit and, therefore share an identity. Each one is also presented as a riff:

Abel Meeropol's elegiac masterpiece, Strange Fruit, is most familiarly voiced, perhaps, by Billie Holiday. 62 It metaphorically turns the tragedy and horror of lynching, through her mournful and haunting supplication and sorrow, into an indictment of it: "Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze / Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees / Pastoral scene of the gallant south… The scent of magnolia sweet and fresh… / …fruit… / for the tree to drop / Here is a strange and bitter crop". 63 These lyrics, selected from equally telling others, convey deep convictions in juxtaposed metaphors—black bodies swinging and strange fruit hanging—and imagery of ironic hypocrisy—Pastoral scene of the gallant south. How difficult it must be, then, to smell the sweet and fresh scent of magnolia and to see its fruit left to rot and drop as only part of an all too familiar and poisoned crop.

Alice Walker's short story, The Flowers, a one-page miracle of storytelling, speaks volumes about the irony intrinsic to this peculiarly American history. 64 Myop, short for myopia and, read backwards, suggestive of her being a living poem, "skipped lightly from hen house to pigpen," evoking the cycle and rhythm of life, i.e., beginnings (eggs) and endings (smoke equaling spirit), and her working out "the beat of a song on the fence around the pigpen." Her state of mind, "the days had never been as beautiful as these," is predicated on "It seemed…." She is "ten, and nothing exist(s) for her but her song," except that in turning towards the spring, and adventure, she starts into new experience, beyond the sharecropper farm where she lives with her mother: "Today she made her own path, bouncing this way and that way, vaguely keeping an eye out for snakes. She found, in addition to various common but pretty ferns and leaves, an armful of strange blue flowers with velvety ridges and a sweet suds bush full of the brown, fragrant buds." She is growing, and circling the land, discovering. At noon, although having "been as far before, …the strangeness of the land made it not as pleasant as her usual haunts… and began to circle back to the house, back to the peacefulness of the morning" when "…she stepped smack into his eyes. Her heel became lodged in the broken ridge between brow and nose, and she reached down quickly, unafraid, to free herself. It was only when she saw his naked grin that she gave a little yelp of surprise." Chilling because it is startling to realize she has stepped into the bridge of a skull, we watch her step back and assess the scene and see her seeing hints of the body, pushing leaves and layers of earth back to see what is to be revealed. Ultimately, she sees much more, but so do we within the hidden circles and truths within the story, her story:

Myop gazed around the spot with interest. Very near where she'd stepped into the head was a wild pink rose. As she picked it to add to her bundle she noticed a raised mound, a ring, around the rose's root. It was the rotted remains of a noose, a bit of shredding plowline, now blending benignly into the soil. Around an overhanging limb of a great spreading oak clung another piece. Frayed, rotted, bleached, and frazzled—barely there—but spinning restlessly in the breeze. Myop laid down her flowers.

Although this body that she discovers had fallen from "a great spreading oak," it is merely one of too much 'strange fruit' that has bloodied American soil, and circling that tree and the man, sadly, in his last moments before his life was snapped, was a ring of hatred, of sneers and jeers and unfriendly faces, strange faces, unkind and unloving. This history recalibrates Myop's awareness, and for her, then, "the summer was over." For readers, though, the realities that Myop has stepped into are infinite and frightening, although she shows no fears. We are left to imagine. I suggest for a place to begin seeing: imagine the pattern the knot of a noose makes, and then pretend to be Myop reaching down to pick that wild, pink rose and, in the process, notice your fist that holds the bundle of picked flowers and see why she "laid down her flowers."

Treasures from the Past – Secrets of the Cave seeks in spirit, I believe, to teach healing by showing love in action and adventure and, in a way, to redress an aspect of that bitter crop. It is the story of William, a struggling reader and son of a white and poor, farming family, and Anna, the daughter of the only black family in the county who is like Myop in that she is unafraid to seek truth and to live in happiness despite hardship and hate. Their discoveries about each other, William cannot read well and Anna "can't go to Bon Aqua School because [her] skin isn't white," begets their friendship (as saintly similes) and adventures, where they soon discover secrets in a cave and, ultimately, experience great adventure in a hot-air balloon with their newly-formed friends and fellow adventurers. 65 How did William and Anna actually meet? When William, during recess from the one-roomed schoolhouse, slipped down to the creek in the woods and saw Anna "leaning against the big oak tree that grew in the middle of the forest" and "as he walked closer, he realized that she was reading a book." 66 Hmm.

On a side note, in The Intentional Fallacy, Wimsatt and Beardsley argue that "the design or intention or the author is neither available nor desirable as a standard for judging the success of a work of literary art" and "critical inquiries are not settled by consulting the oracle." 67 I agree, but still I offer my mother's words of intent:

In 1998, Stafford A… encouraged me to write about my years growing up in the South. My thoughts drifted back to 1946, the year that our family moved from the city to a farm near Bon Aqua, Tennessee. It was a big change for me to live the life of a country girl; not only did I feed the chickens, milk the cow, and work in the garden, but I also attended classes in a one room schoolhouse during a time when segregation was being experienced throughout the South. Having lived through those times, I wanted to share about the hardships inflicted on some Americans as seen through the eyes of a child. While the persons and events in Secrets of the Cave are fictional, the problems brought about by segregation are real. 68

She was once a struggling reader, too, having suffered a childhood illness that set her back and triggered the onset of fears; yet, she overcame! In talks with her about this curriculum, she reminded me about the nursery rhyme Mary Had a Little Lamb: "it followed her to school one day / which was against the rule. // It made the children laugh and play, / to see a lamb at school." 69 In the mindset of William Blake as voiced by Frye: "The more a man puts all he has into everything he does the more alive he is." 70 Thus, allow children serious passion and play!

Comments: