Topic Research

Four artists will be the focus of this unit: John Trumbull, Tompkins H. Matteson, Eyre Crowe, and Eastman Johnson. We will also study photographs from the African American Collection of Randolph Linsly Simpson, housed in the Yale Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, documents and artifacts from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website, and the Learn NC website.

John Trumbull/Tompkins H. Matteson

Essential Question: How can art allow us to understand an earlier era?

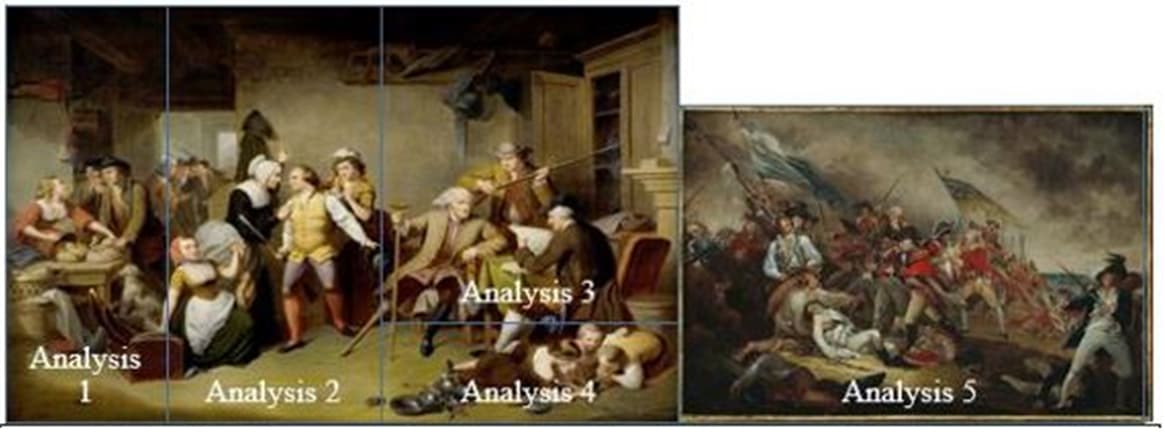

Figure 1: The Spirit That Won the War, Tompkins H. Matteson, 1855/The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker's Hill, 17 June, 1775, 1786 2

In the first painting, The Spirit That Won the War, which was painted seventy years after the war, there are several groups of people who, when separated from the whole, seem to be telling different stories than the whole painting. Matteson's intentions were to show a young man readying for war. Instead, he may have romanticized the war. He was not an actual participant and could only speculate the events. According to the Chrysler Museum of Art website,

Within this stirring portrait of a Revolutionary War Minuteman preparing for battle, the artist includes multiple centers of activity. In the lower right, children melt kitchenware to make bullets. Behind them, a veteran of an earlier war who looks on while another man reads news of the Declaration of Independence. To the left, a woman greets two armed men at the door, while yet another group prepares food and weapons. At the center of the painting, three women flank a young man: one woman provides instruction, another secures his knapsack, another offers him a satchel. He looks into the eyes of the woman to his right, possibly a tender moment between mother and son. Each group plays its part in sending a young man to war, aiding in his hopeful victory. The artist, Tompkins H. Matteson, has captured the variety of emotions associated with historic events, between family members and friends and from children to elders. 3

Once taken apart, the painting seems to take on a different feel. The lady on the left could be flirting with the gentleman at her table, the children on the right could be playing with some sort of toy, and the ladies in the middle could be chastising the young man for bringing a gun into the house. However, when the painting is put back together, it takes on a new meaning. The emotions within the faces of the people are also shadowed by the darkness of the ceiling. This can be interpreted as a sublime sense of foreboding for the war is beginning and maybe this young man will not come home.

Next, we will compare the painting to John Trumbull's, The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker's Hill, June 17, 1775, which was painted about ten years after the war in 1786, but by John Trumbull, who was actually present for the event depicted in the painting. This portrayal, which could also be construed as romantic, shows a much more realistic depiction of the war and its ravages. However, when researching the painting, it is learned that this is actually a painting that depicts courage and honor amidst the destruction. As stated in the Yale University Art Gallery's eCatalogue, the painting demonstrates a deeper level:

Trumbull represents the climactic moment when the British successfully break through American lines, resulting in hand-to-hand combat. He shows the victorious British Major John Small magnanimously protecting the mortally wounded American General Joseph Warren from being bayoneted by a grenadier, who means to avenge the death of an officer who has fallen at his feet. By portraying the courage and sacrifice displayed by both American and British officers, Trumbull hoped to convey the message to future generations that honorable behavior transcends national boundaries. 4

Students will compare the two paintings to discover the differences and similarities that are both courageous and cowardly, humane and inhumane. Which painting is more accurate of the war? Which painting shows inhumanity? Students will provide evidence to back their claims.

Eyre Crowe

Essential Questions: How does art represent the values and morals of a society? How do the people feel? What is their value? How does the painter capture the pain and trauma?

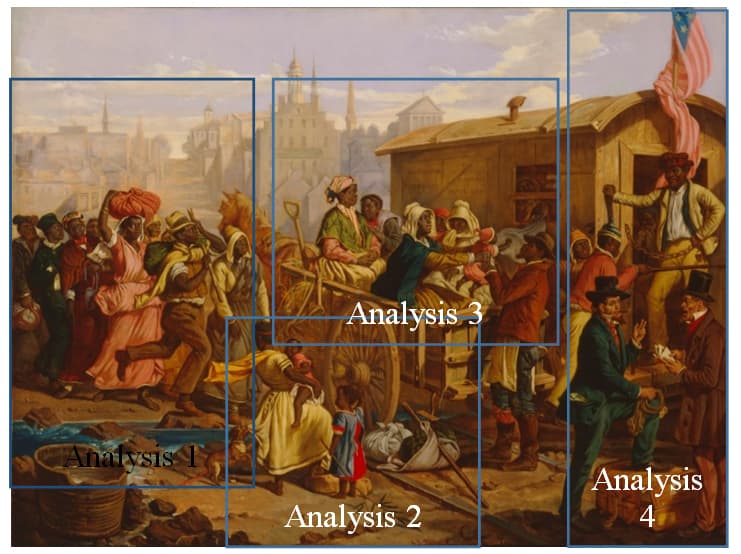

Figure 2: After the Sale: Slaves Going South from Richmond, Erye Crowe 1853 5

Eyre Crowe hailed from London, England and came to America in his early twenties with a famous author named William Makepeace Thackeray. Together, they documented the Slave Trades in the southern United States, namely Richmond and Charleston, Virginia, and New Orleans, Louisiana. Thackeray wrote; Crowe painted. While many of the paintings from the mid-19 th century focused on Westward expansion, and flowed from right to left or east to west, Crowe's painting flows in the opposite direction, perhaps signifying that slaves were not free to explore. He also has cut the painting in half with the muted skyline against the vivid action of the slaves preparing to board the train.

The train itself is new to the way slaves were transported from city to city. In her book, Slaves Waiting for Sale: Abolitionist Art and the American Slave Trade, Maurie D. McInnis outlines the use of the train by explaining,

Crowe's depiction of the railroad as a key element in the slave trade emerged from his observations and was not part of the traditional slave-trade iconography. For decades before his visit to Richmond, slaves had generally been marched to the lower South in large groups referred to as coffles. In the 1850s, such coffles became less common as railroad lines came to cover more and more of the South. Traders increasingly relied on the railroads to transport slaves, because it was much quicker than the seven- or eight-week journey by foot, and slaves usually arrived in better physical condition. 6

This knowledge will help students to understand the treatment of the slaves as they were sold. It might also factor into the students' final analysis of the painting. The painting is in four sections for analysis before students see the entire painting. This allows them to understand and characterize the people before they see what is happening to them.

Eastman Johnson

Essential Question: Can humankind learn from its historical rights and wrongs?

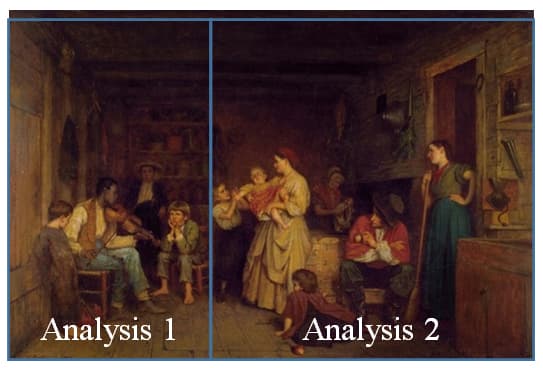

Figure 4: Eastman Johnson, Fiddling His Way 1866 7

Patricia Hills, in the text, Eastman Johnson Painting America, references the two versions of Johnson's paintings, which are both titled, Fiddling His Way. Shown above, is the version that features an African American fiddler. The second version, which is in the private collection of Howard and Melinda Godel, features a Caucasian fiddler. It will be used as the third analysis and can be found here http://goo.gl/7mhOvN. Does having the fiddler change from black to white make a difference in the story the painting is telling? What clues are in the painting that indicate if it does or does not. Hills tells us about a critique of the painting:

The third picture that the writer mentions is Fiddling…The African American gets mention only in passing. The writer clearly finds more appeal in Johnson's evocation of "purity and peace," so desperately yearned for that February 1865…The critic makes only the briefest reference to the race of the fiddler, as if Johnson could just as easily have substituted a white man for the black man. And, in fact, he did. In the 1907 estate sale of Johnson's work another version, also called Fiddling His Way, was described in the catalogue as 'a simple New England interior' in which 'an old fiddler, apparently on the tramp, is playing his violin, surrounded by the farmer's family.' In that work, Johnson had replaced the young, virile, African American with an old New Englander. The painting never sold in his lifetime. 8

It is unclear why Johnson made the changes he made in this painting. Perhaps the Terra Foundation of American Art had made the best claim, "When he substituted an elderly white fiddler for the black player, however, Johnson signaled his increasing artistic interest in rural New England life." 9 Could it be that simplistic? Students will compare and contrast the two paintings and write an information/persuasion essay to answer the essential questions above, which will become a part of their student portfolio.

Randolph Linsly Simpson, African American Collection

Essential Questions: Does history repeat itself? Can humankind learn from its historical rights and wrongs?

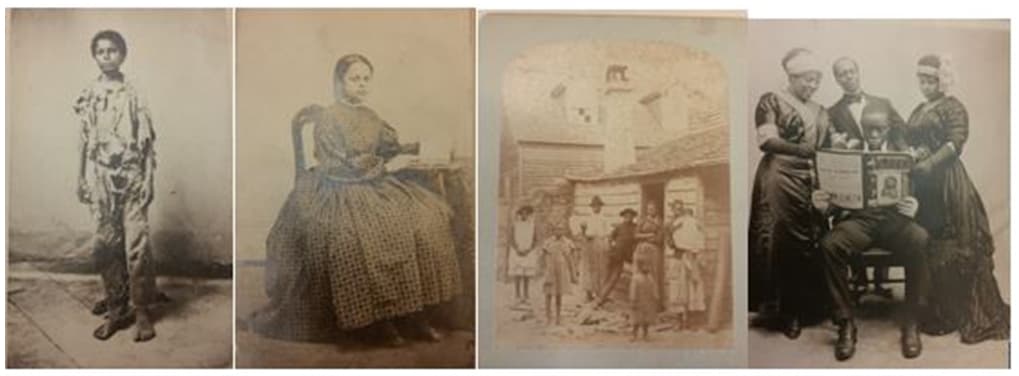

Figure 5: Rudolph Linsly Simpson, African American Collection at Yale Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscript Library 10

The next medium students will explore is photography using the collection of Randolph Linsly Simpson, which is housed in the Yale Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. The sample photos I have chosen depict various scenarios in early African American life. They range from wartimes (Civil War) to peacetime, but clearly show what life was like in early America. For the activity below, students will have a large variety of photographs from which to choose.

Randolph Linsly Simpson began collecting African American photographs and memorabilia with his knowledge of his own family's abolitionist history as well as having grown up in the area of Rochester, NY where Frederick Douglass is buried. According to the library summary, Simpson's collection includes many artifacts produced by both white and black photographers. Although the focus is on African American history, the collection includes images of white men and women who were a part of the abolitionist movement. The images contain a range of socio-economic classes and include the works of various photographers. It also contains several different processes of photography such as Daguerreotypes, tintypes, paintings, and drawings. The collection contains famous people such as Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King, W. E. B. DuBois, and Sojourner Truth. However, in this unit, the focus is on the lesser-known people such as domestic servants, emancipated slaves, soldiers, and everyday people. 11

World War I Propaganda

Essential Questions: Is an informed citizen a good citizen? What role does artwork and propaganda play throughout the human experience?

During wartime, posters were created to inform and incite the population to support its troops who were battling the enemy. In continuing the theme of analyzing African American historical paintings and photographs, the next logical step is to explore how propaganda was directed to this population. In the text, Picture This: World War I Posters and Visual Culture, edited by Pearl James, there is a chapter that specifically describes these types of propaganda. "Images of Racial Pride: African American Propaganda Posters in the First World War," by Jennifer D. Keene, specifically refers to the fact that African Americans were in prime shape to advance the civil rights agenda by showing their willingness to participate, sacrifice, or even die for their country. 12

Specifically, I will be using the following posters:

- "Emancipation Proclamation, September 22, 1862" by E. G. Renesch. The economic, intellectual, and military contributions of African Americans to the war effort became the basis for demands that the nation fulfill Lincoln's promise to ensure all Americans equal rights. This poster is located in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

- "True Blue," 1919 by E. G. Renesch. This seemingly conservative portrait of a patriotic African American family raised fears among southern whites that material progress and wartime sacrifices were responsible for the new "insolence" and militancy evident in the civil rights movement. This poster is located in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

- "Colored Man Is No Slacker" by E. G. Renesch. Official government agencies and private publishers freely shared and exchanged images during the war, attaching captions or placing them within a context that dramatically altered an image's meaning. This privately produced poster, which initially underscored African Americans' voluntary contributions to the war effort, was transformed by the government into an image of a venereal disease– free soldier returning home to his family. This poster is located in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Each of these posters represents what life could be like for the African American soldier. Analysis of these posters will commiserate with a reading of the chapter noted above. This will be the first actual reading piece for the students. They will learn that propaganda from the government aimed directly at the African American population was designed to influence their wartime behavior and give them a sense of patriotism that came with the civil war. However, private propaganda did the opposite. This cast a shade of doubt that the African Americans were given credit for their patriotism enough to die for this country. Moreover, according to Keene, "All wartime propaganda emphasized the key role that blacks played in the domestic economy and highlighted their hero- ism on the battlefield." (Keene 2009)

World War II Images of The Holocaust

Essential Questions: When is violent language a crime 13 What is genocide? Has it been going on longer than we think?

World War II brought the word genocide into the world's vocabulary. It also brought to the forefront the language used to incite violence toward a group of people. As described on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) website, incitement means, "encouraging or persuading another to commit an offense by way of communication, for example by employing broadcasts, publications, drawings, images, or speeches." 14 Propaganda was used during this time to incite negative thoughts and feelings regarding the Jewish population. This was crucial to Hitler's plan to rid the world of the Jews. He needed to have his country on board with his ghoulish plot. As history showed, this plot was successful until the end of July 1944 and into the beginning of the year of 1945 when the prisoners were liberated by the Allied forces.

To invoke emotional empathy from our students, they will analyze a large variety of propaganda posters from this time, many of which are in German, alongside photographs of the inhumanity that was The Holocaust. On their own, students will use classroom technology to explore the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum's website to guide them in their writing in the activities section below. Students will find their own examples of propaganda and images to present their writing to the class by accessing the Themes page of the USHMM. Here, they will find the following themes: "Making a Leader", "Indoctrinating Youth", "Rallying the Nation", "Defining the Enemy", "Writing the News", "Deceiving the Public", and "Assessing Guilt". The images used will depend on the student and his or her analysis needs. This is also a part of the culminating project described in the activities below. Students will learn to use propaganda in a good way for the good of their neighborhood by designing actual propaganda to place in and around the school to help ward off the violence and gangs that are prevalent. They may use the same theme titles for their work.

Comments: