Classroom Activities

34

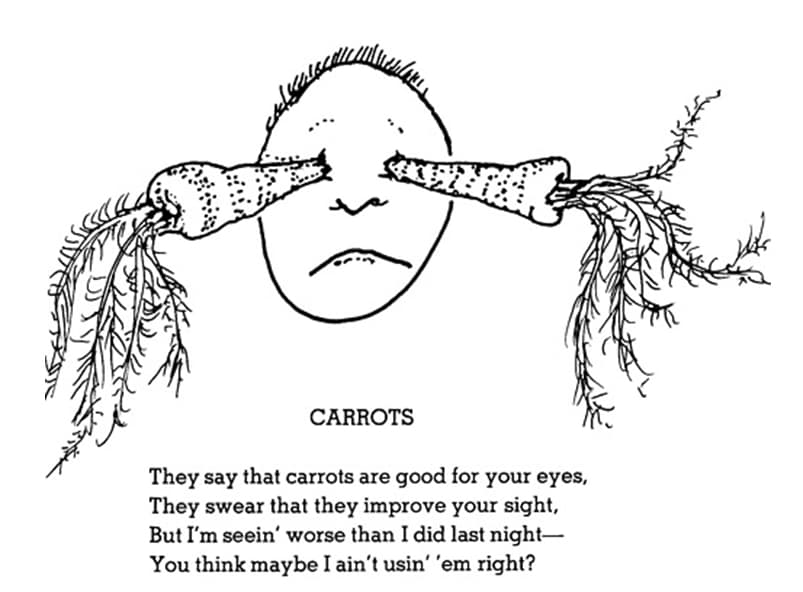

Make learning fun! To hook the students into the unit, start class by reading aloud Shel Silverstein's "Carrots" 35 while wearing glasses or an eye mask with carrots attached. This is how I attached the carrots on my sunglasses when I recited the poem:

No doubt the students will laugh at the poem if they aren't already laughing at you. Ask the students, what is the proper way to 'use' carrots? This is a great way to incorporate humor and begin questioning between the relationship between the poem and the visual illustration. As a whole group or in pairs, you could also discuss if they have ever misunderstood what someone told them?

The classroom activities are presented in three stages to have students engage through critical thinking, expand their ideas in collaboration, and explore their creativity and share through communication. While all teachers may not be able to dedicate the same amount of classroom time for this project, I think it is useful to select what will work best in your classroom. As with reading levels, students arrive in our classrooms with varying degrees of skill in drawing. Likewise, these activities are differentiated and intended to have every student be successful.

Engaging Through Critical Thinking

Finding the meaning in an artwork or a poem can be daunting but we approach both, using a similar skill set, observation. Dominic Lopes says "no picture is seen with an innocent eye, because we come to pictures primed with beliefs, expectations, and attitudes about systems of representation." 36 Through critical thinking, students can discover that they hold the keys to unlocking the meaning of a poem or work of art.

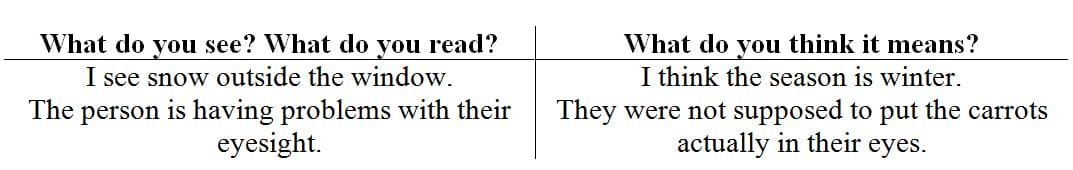

In Percy Jackson and the Olympians, the character Apollo states, "You might as well ask an artist to explain his art, or ask a poet to explain his poem. It defeats the purpose. The meaning is only clear thorough the search." 37 Viewers of any age can search through poetry and art to decipher their own meaning. When you think about it, we use art and poetry in our everyday lives. Ask students, what is art? and what is a poem? Once they recognize that art can found in video games, clothing, advertising, packaging, picture books, etc. they begin to see art is accessible. Similarly, poems can be found in songs, nursery rhymes, mnemonic devices, children's books, etc. Many students by fourth grade have written poems in an acrostic form, using the letters in a word to begin each line of the poem. To analyze an artwork and poem, there three basic questions — "What do you see/read?" "What do you think it means?" "What do you see that makes you think that?" I would recommend first working together as a whole group to model interpretation. Organize and group your thoughts on a t-chart. Graphic organizers are useful to help student organize their thoughts and derive conclusions. The left column will display what you actually see or read and the right column will display your interpretation of what you see. Ask the students to spend a quiet minute to look at the picture or read the poem. Ask the students what do they see or read and add the students' answers to the left column of the t-chart.

Next begin the "Think, Pair, Share" strategy by asking the students to think about what is going on in the picture or poem. After about thirty seconds, have students discuss with the person next to them or their table group what they thought. Circulate through the room to monitor conversations and assist to facilitate as necessary. Have the students continue the discussions for a few minutes. Finally, ask a pair or group to share one of their findings, and ask them what do they see/read that makes you think that and add the responses to right side of the t-chart, as seen below. If more than one student/group finds the same conclusions make a tally or mark the duplicates. Ask the students to reflect on their overall conclusions: "Did we reach the same conclusions and meanings?" "Is it possible to have more than one correct answer based on a different viewpoint?"

Students may find it easier to have a written prompt to refer to while they identify and interpret the works. I like to add clip art images next to the list or question to help students with reading challenges in deciphering the words. For example, next to the question, "What do you see?" would show a big pair of eyes or a pair of binoculars.

Prior to implementing this unit in your art classroom, I suggest asking the grade level teachers, a reading specialist or a reading coach what the student learning objectives specifically focused on at your school. Other ways of seeking meaning can be investigated by discussing, who is the speaker? Is the author or artist the character represented? What is the author's or artist's purpose of the work — to persuade, inform or entertain?

Helen Plotz writes, "for science and art – or poetry, if you will – are alike, dedicated to exploring and questioning." 38 Students with more experience in art might dissect an artwork by identifying how the artist used the elements of art. The Elements of Art are the 'tools' that artists use to create a work of art — line, shape, color, texture, space, value, space. Students in some schools might recognize the use of figurative language in poetry such as alliteration, rhyme, personification, simile, and metaphor. Create a list of figurative language examples to use as a resource for creating a poem later in the unit.

Expand Ideas Through Collaboration

Collaboration will allow students to become more confident in their analysis and creation of poems and art works. Depending on the amount of class time, there are many ways to have students work together. As a warm-up activity or exit strategy, the students can play Exquisite Corpse. In the early 1900's, a group of artists called Surrealists played a game they named Exquisite Corpse. To begin the game, a sentence or phrase format is chosen, as in adjective-noun-verb. The each participant writes their phrase on a paper, folds the paper to hide their phrase and passes it to the next participant who continues the pattern until everyone has written one phrase of adjective-noun-verb. The first student might write, "adventurous astronaut air-walks" and the next student may write, "silly girls hopscotch." To differentiate among different learning levels, pair or group students and model the first phrase line of the poem.

Haikus are also approachable for elementary students. Ask students to write a haiku, a poem consisting of three lines of five syllables, then seven syllables, then five syllables. After the haikus are written, ask students to work in pairs to illustrate each other's poems. Another cooperative activity, the teacher may choose to assign each student or group a line of a poem from Shel Silverstein's "Eight Balloons" 39 or "A Closet Full of Shoes" 40 to illustrate. After the illustrations are complete, each student or group can present their illustration and read aloud their assigned section of the poem.

Explore Your Creativity and Share Through Communication

In art, the importance of the process of creating is equivalent to the outcome of the final product. Each student should be evaluated with a rubric and with reference to the best of their own ability. In my opinion, all students' work should not look identical. When choosing the poems to introduce to your class, find ones that you enjoy reading. Just like our students, we are all different. As teachers, our enthusiasm is transparent even to the naivety of children. They will see your smile and find your enchantment with the poem contagious. Through a read of Silverstein's collection of poems, A Light in the Attic, I earmarked three dozen poems that would enhance this unit.

Introduce the students to your favorites from the collections of the funny and quirky poems and drawings by Shel Silverstein. I recommend finding a YouTube recording of Silverstein reading one of his poems. His voice is unique and who better to read than the author himself! Read aloud or ask for volunteers to read aloud, poems that have interdependent illustrations or where the illustrations further the imagination of the reader but do not show the class the drawing. Ask the students to infer the meaning of the poem. After several responses are shared, show the students the interconnected illustration. Discuss if their predictions are accurate and how the image changes the meaning. Repeat the same exercise with "Sun Hat," 41 "Turkey?," 42 "Stupid Pencil Maker," 43 "Cookwitch Sandwich," 44 "The Runners," 45 and "Snake Problem." 46

After seeing several examples of Silverstein's drawings, ask the students to describe his art work. Referencing the elements of art, fourth grade students should be able to discuss color, line, shape, space and texture. Students should recognize that there is no color in the work, just black outline on white paper. Students should note how Silverstein typically shows space by drawing a horizon line to give the characters a place to stand or run, as seen in "The Runners." 47 Ask the students to describe how they can build a picture using shapes and then look for general shapes in Silverstein's drawings, like the rounded triangles to create the carrots. Point out how Silverstein showed texture by changing the way he draws the lines, as illustrated in the dots and dashes to describe the undulations on the carrots.

Activate the students' prior knowledge from science by reading "Moon-Catchin' Net" 48 and "Somebody Has To." 49 If time permits you could also introduce poems that do not have an illustration attached, for example, "Go Fly A Saucer" 50 by David McCord. Ask the students to list the places they could visit in a spaceship based on what they learned in their science unit. The list could include sun, Mercury, Venus, Moon, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, Pluto, galaxy, comet, star, etc. Write each on a separate piece of paper and spread around the room. Group the students in pairs and have them 'carousel' around the classroom. With each group starting at a different location, have the students list characteristics of that place in the solar system. After one to two minutes, indicate for the students to rotate counter-clockwise and add more characteristics to each place. The rotation indicator could add an element of amusement by having a tone sound like 'blast off' or play a song, "Weird Science" by Oingo Boingo. As they rotate, if they had the same idea as someone before them, instead of having 'rings' written several times to describe Saturn, each group should place a checkmark next to the word. Continue the carousel rotation as time permits or until all the possible traits are listed.

Using the student generated solar system traits list, each student will choose an aspect of the 'Sky Watchers' unit to develop a poem. While they are brainstorming ideas for their poem, encourage them to doodle and draw on their paper. Circulate the room to provide feedback and suggestions for students on developing their poems and illustrations. Next, direct the students to refer to the list of poetic references you created to incorporate in their poem. Allow them to choose the poem format the "speaks" to them. It could be a haiku, free verse or rhyming poem of at least three lines. Give the students a paper to fold in half twice and make four different thumbnail sketches of their drawings. Each sketch should be a different picture relating to the poem they wrote. Refer to the elements of art as the students draw and encourage the student to extend, add details and rework to improve their drawings. Once the poem and illustration are finalized, have the student transfer them onto a piece of drawing paper in pencil. To create a finished appearance, they should trace over their pencil lines with a thin tip black marker. Allowing each student to have a choice of the type of poem and solar system location provides an opportunity for students to gain a personal connection with the work. Their personal connection is then deepened by making creative decisions about how they would experience their out-of-this-world exploration.

Finally, the students will communicate their ideas through the words of the poem and through the picture of the planetary adventure with the school community. Their final work can be shown collaboratively and displayed on a bulletin board, combined into a book for each student to keep, scanned into a digital slideshow, or record each student reading their poem while displaying their drawing in a digital story.

Aileen B Welsh

November 11, 2015 at 2:02 pmWow, I am impressed.

Kristen, I was searching for some information on my upcoming Science unit and your project came up in the search. I briefly read over it and although it doesn't fit the content of what I am doing in Science I enjoyed it. Aileen

Yuka Kazahaya

September 25, 2020 at 3:11 amInteresting!

This article is so impressive. I have been studying the relationship between Shel Silverstein's poetry and his drawings. I really like his picture for \\"CARROTS\\" which originally sparked my interest in his work. I have also been interested in Edward Lear for many years. In this article you mentioned about his work, too. I think we need something fun like Silverstein's poetry and drawing to enjoy our life under this corona virus. Thanks again from Japan.

Comments: