Classroom Activities

Lesson 1 – What Exactly Is a Function?

I expect this lesson to take two to three 90-minute block periods. At the end of the lesson, students will be able to identify functions from multiple representations and specify the domain and range, and also the image, for each.

Activity 1- Introduction

To begin, I will use the "Function Wall" Activity from the NCTM book Putting Essential Understandings of Functions into Practice 10 to lead students to understand the definition of function. (Because it is not an original activity, I will only explain the basics here.) First, place letters A through D at different places around the room. Then assign characteristics to each letter, and tell students to stand by the letter that matches their response to a question. For example, the question may be "What is your age?" If A represents "over 18 years," B represents "over 17 and up to and including 18 years," C represents "over 16 and up to and including 17 years," and D represents "under 16 years," then each student should go to one of the letters A through D without confusion. In contrast, if the question is "Who lives in your home with you?" and A represents "mother," B represents "father," C represents "brother," and D represents "grandparent" then there will most likely be confusion because students may live with both parents, or may live with a mother and brother. The fact that there is confusion means the relation between the student and with whom he/she lives is not a function.

A second introductory activity that I will adapt to help students recognize functions from different representations – words, table, graph, or formula - is from the same book as above. Each problem gives two set names and asks whether one set is a function of the other. For example, set A is named "Date", and set B is named "High temperature of the day." Students can be asked whether set A is a function of B, i.e. whether the date is a function of the high temperature. Since more than one date can have the same high temperature, the relation is not a function. Students can also be asked whether set B is a function of A, i.e. whether the high temperature is a function of the date. The answer is yes, because there can only be one high temperature for a given date. Asking about the same two sets in two different ways should help students really focus on the definition of function.

Activity 2 – Working with Domains

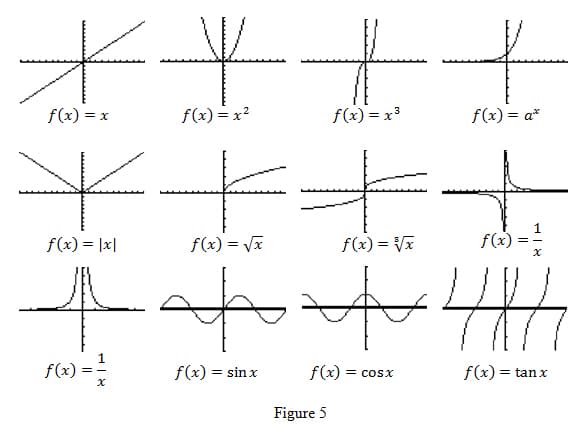

To start, students will look at graphs of familiar function families (linear, exponential, square, cube, square root, etc.). They will record the definitions of domain, implicit domain, range and image, and identify the implicit domain and estimate the image from the function family graphs shown in Figure 5. In particular, I want them to recognize how maximum, minimum, and undefined values in the domain and image appear in the graphs. Finally, working in small groups so they can discuss observations and sort out the definitions in different scenarios, students will complete the Lesson 1, Activity 2 worksheet given in Appendix C.

The closing activity for this lesson comes from the March 2013 issue of Mathematics Teacher. 11 It contains a set of 37 cards containing equations, tables, graphs, and written descriptions of scenarios. The general instructions are "Sort the cards and be prepared to explain your categories with others." Again, students will work in small groups. The sorting can be as basic as function and non-function categories, or it can distinguish function families (linear, exponential, periodic, etc.). There are some cards that are included to generate discussion. For example, one card has "y 4 = x" printed on it. Some students may claim it does not represent a function, but since the directions do not specify that y must be a function of x, it is worth pointing out that, in this case, x is a function of y. Another example is a card that contains a table of x and y values that appears to follow the rule y = 3x with the exception of one outlier. Since every x value in the table maps to a single y value, the table does represent y as a function of x. It is good reinforcement for students to remember that functions do not necessarily need to be written as formulas.

Lesson 2 – Making New Functions From Old

I expect this lesson to take three to four 90-minute block periods. At the end of the lesson, students will be able to calculate and state the domains for the sum, difference, product and quotient of functions from tables, graphs and formulas. They will be able to write and perform function composition, and describe function transformations as function composition.

Activity 1 – Function Operations: Arithmetic

Textbooks typically provide practice with the basic function operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication and division, so I won't include examples here. In the interest of precision, I will insist that my students record the domain for each original function and the final result whenever appropriate. I have included some examples of performing operations from values found in graphs (without the formula provided), along with a sampling of word problems on the Lesson 2, Activity 1 worksheet in Appendix C.

Activity 2 – Function Operations: Composition

To introduce the concept of function composition, I will use real-world problems that students can solve by performing multiple steps without using functions explicitly, including some in my Core Plus 4 textbook. For example, suppose the cost to rent the local fire hall is $250. If they charge $15 per person for food plus an 18% gratuity on the total bill, what is the total cost for the event? Students can calculate the total cost given the number of attendees, or they can write two (affine) functions and use them in succession. The two functions are f(n)=250+15n, for the room and food, and T(f)=1.18f=D_1.18*f for the total cost, including gratuity. It should not be a stretch to combine these two functions by composition, essentially substituting f(n) into T(f); only the notation (T*f)(n)=T(f(n) )=1.18(250+15n)=295+17.7n will be new. We also need to discuss domains and images for composition. Since we are substituting f(n) into T(f), the image of f(n) must be part of the domain of T(f). In this case, since we can multiply any number by 1.18, the composition can be performed.

Illustrative Mathematics "The Canoe Trip" 12 task presents a situation in which the speed of the current of a river affects the paddler's speed. By completing a table of values, students recognize the pattern and write equations for the paddler's actual speed and the time to complete the trip. If R(c) is the paddler's speed as a function of current speed, and time to complete the trip is a function of the paddler's speed, T(R)=d/R for a specified distance, d. Therefore, T(R(c)) gives the time as a function of current speed. Once again, discussion about the domains and images of both functions is required to force students to consider feasible inputs and outputs for all functions. Resources for additional word problems that apply function composition are listed in Appendix B.

Somewhere in the middle of the lesson, I will have students practice composition, as a skill only, with a relay race game that I found at the BetterLesson website. 13 For the game, a team of students divides a list of functions (written as formulas on cards or on the board). The teacher calls an input number and the 1 st student in each team evaluates f(n) and passes the output to the next person. The 2 nd student evaluates g(f(n)), the 3 rd evaluates h(g(f(n))), etc.

After a few rounds of the relay race the energy level in the classroom should be raised enough that students can move on to examples of compositions that cannot be performed for all values of the independent variable. As I demonstrated in the Background section, when the image of one function differs from the domain of the other, composition may not be possible, or it may exist only for a restricted interval. Practice is provided on the Lesson 2, Activity 2 worksheet in Appendix C.

Activity 3 – Transformations as Compositions

In this activity, I will build on textbook activities that have students explore and practice transformations of basic function families. Specifically, I will emphasize how the procedure for "completing the square" to rewrite a quadratic expression helps us visualize transformations to f(x)=x^2. Let's start with q(x)=3x^2-4x-8. The first step is to divide the first two terms by the leading coefficient to get q(x)=3(x^2-4/3 x+?)-8. The question mark is waiting for the value that will form a perfect square in the parentheses – ½ the coefficient of x, squared – (2/3)^2=4/9. We need to keep the expression the same, so we apply the Identity Property of Addition to get q(x)=3(x^2-4/3 x+4/9-4/9)-8=3(x^2-4/3 x+4/9)-3" 4/9-8=3(x-2/3)^2-28/3. From this form of the quadratic function, we can see the transformations: horizontal shift to the right 2/3 units, vertical stretch factor of 3, and vertical shift down 28/3 units. Furthermore, we can write these transformations as a composite of the following transformations: (1) f(x)=x^2; (2) g(x)=(x-2/3); (3) h(x)=3x; (4) j(x)=(x-28/3); (5) q(x)=j(h(f(g(x) )).

Unless the domain is restricted based on the problem, the domain for all of these transformation functions is (-∞,∞). The image for q(x) is [-28/3,∞), as determined by the vertical translation. Since vertical translation is the last transformation, performed on the output, it does not restrict the domain of the other transformations. I will provide abundant practice with this procedure to determine the transformations of quadratic functions. The task entitled "Building an Explicit Quadratic Functions by Composition" on the Illustrative Mathematics website provides additional practice, and I will create additional problems similar in structure for other function families. For still more practice, I will alter the instructions for the Illustrative Mathematics task "Domains" to ask students to write the list of transformations starting with a transformed function and working backwards to the basic function family. Of course, I will still require them to state the domain for each transformed and basic function. At the end of these activities I will assess students' ability to use function composition to perform transformations.

Lesson 3 – All About Inverse Functions

I expect this lesson to take approximately three 90-minute block periods. At the end of the lesson, students will be able to define and recognize one-to-one functions, define the Identity function, find and verify (simple) inverse functions by composition, and restrict the domain of a function to make it invertible.

Activity 1 – What Types of Functions Have Inverses?

As a Warm-up activity, I will ask students to solve the following equations for x:

Once students have the solutions, I will ask this series of questions to lead them to understand the definition and the significance of one-to-one functions:

- Which of the equations above have more than one solution? (#2, 5, 8)

- If the right-hand side of each equation were replaced with y, what do the graphs of these functions look like?

- For equations #2, 5, & 8, is y a function of x? Explain. Is x a function of y?

This extended warm-up, will provide examples, and non-examples, to informally assess student understanding of one-to-one functions: each input leads to a different output.

Next, I will ask students questions like "What is the additive inverse of 5? -2? 0?" and "What is the multiplicative inverse of 5? -2? 4/3?" to refresh their memories on the term inverse. Then, just like a number plus its additive inverse equals the additive identity, 0, and a number multiplied by its multiplicative inverse (reciprocal) equals its multiplicative identity, 1, a function composed with its inverse equals the Identity Function. The Identity function is f(x)=x, which is the line that forms a 45° angle with the x-axis. Before moving on, students should practice recognizing one-to-one functions and composing functions to verify that they are inverses. Sample problems are given on the Lesson 3, Activity 1 worksheet in Appendix C.

Activity 2 – How to Find an Inverse

With vocabulary taken care of, students are now ready to practice finding inverse functions. First they will find inverses in context so that the variables have meaning and to help understand the notation f^(-1) (y)=x for f(x)=y, and then for any algebraic formula. I will refer back to the warm-up problems in Activity 1 to help students make the connection that they already know how to use inverse operations to "undo" and solve algebraic equations, and that inverse functions "undo" functions. Therefore, when solving equations of one-to-one functions, we can work backwards (undoing) from an output to find its corresponding (only) input. With practice, students should recognize that all (non-constant) affine functions have inverses, and finding them is like solving linear equations. Students will state the domain and image for simple functions and their inverses, looking for any relationships between them. When appropriate, students will graph both the function and its inverse, adding the line representing the Identity function, f(x)=x. Students will also find the intersection between a function and its inverse to recognize that it always lies on the line representing the Identity function. Sample problems beyond typical textbook problems are given in Appendix C on the Lesson 3, Activity 2 worksheet.

Activity 3 – How to Make a Function Invertible

Several problems in previous activities (#2, 5, 8 in the warm-up for Activity 1, D(x) and P(x) on the Lesson 3, Activity 1 worksheet, and several of the contextual problems on the Lesson 3, Activity 2 worksheet) may have already generated discussion about restricting domains so that a function has is invertible. Students most likely have observed that graphs of parabolas and absolute value are not one-to-one, and therefore, not invertible as is. General formulas with squares (or higher degree polynomials) do not have inverse functions, either. However, if we restrict the domain, they may become invertible. In this activity, students should go back to all previous activities to find functions for which there was no inverse, and restrict the domain so that there is. Additional problems such as "Find a domain for f(x)=3x^2+12x-8 on which it has an inverse" followed by class discussion would provide informal assessment of students' understanding. The discussion should include comparison of students' restricted domain and justification (critique) for its validity. Such a discussion will demonstrate that restrictions are not unique; I will present additional options for domains if students don't do it naturally. This discussion leads naturally to my ultimate goal for the unit – restricting the domains for trigonometric functions so that they are invertible. I will end this unit here with the belief that my students are better prepared to understand inverse trigonometric functions and how to use them to solve trigonometric equations.

Comments: