Narrative Art

Narrative art tells a story, either as a single moment in time or over a series of events. Students will use several rich pieces of narrative art to build their capacity to interpret and respond to works of art that tell a story. The four pieces below address not only seminal events in world history, but they tell a story that will lead to instructionally rich discussion and thinking. In order to facilitate conversations about each piece, it is important for teachers to have some contextual information to ground the discussion. After information about each, I provide questions that could be used to discuss each work as well as a graphic organizer for students to use to explore each work.

George Washington Crossing the Delaware by Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze

George Washington Crossing the Delaware by Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze (4)

George Washington Crossing the Delaware by Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze shows George Washington and a group of soldiers in a small boat crossing the Delaware River; it is considered to be both romanticized and inaccurate. (5) It suggests that the soldiers are going to launch a surprise attack on the British troops. The popular retelling of the event is that during the American Revolution, the Continental Army struggled under the leadership of George Washington, losing control of New York City and other key points in the colonies. In hopes of catching the British army off guard, they planned a surprise attack that involved crossing the Delaware River with 5,400 troops to engage the other side at Trenton, New Jersey. Attacking on Christmas night, Washington and roughly 2,400 troops crossed the partially frozen river in three locations, reaching the New Jersey side before dawn. The rest of the troops he had at his disposal met up the following morning to descend upon the British side on December 26th. The British side was outmanned and underestimated the ability of Washington’s men because of a series of successes. Almost 1,000 British troops were taken captive and news of Washington’s victory “raised the spirits of the American colonists, who previously feared that the Continental Army was incapable of victory.”(6) While that general retelling is accurate, Leutze romanticized a few other parts. For example, the crossing was at night under the guise of poor weather conditions. This differs from daylight that is included in the painting. Washington also didn’t lead the charge; he and 40 others crossed the Delaware led by William Blackler, “a salty, savvy Massachusetts fisherman who most certainly would never have permitted Washington, rank be damned, to stand during so treacherous a crossing.” (7) Leutze’s interpretation of the event creates a much more powerful narrative than having Washington restrained at the back of a boat.

In the painting, Leutze depicts Washington as a decisive and powerful leader. Washington stands taller than all of the other figures in the piece; he is also almost centered in the piece next to the American flag. He holds a brass telescope, wears a heavy saber, and is flanked by another future president of the United States, James Monroe. A bright star shines upon him as if he was chosen by God to conduct this battle. The river is filled with ice, and the boat is filled with 13 men that represent “a cross-section of the American colonies”….an African American, a New England seaman wearing a tarpaulin jacket, a Scottish immigrant, a rower with an unclear gender designation, a woman, riflemen, farmers, a merchant, and even someone who appears ill with a bandaged head. (8) All of these people represent the various trades and colonies; all have a common cause to see the Revolutionary Army win. There is forward movement and momentum in the piece as it moves from right-to-left; this victory had the same impact for the Revolutionary Army. This movement forces the viewer to read the ship, as most viewer’s eves are habitually trained to view from left-to-right. In this reading, it becomes clear that the victory that created momentum and sustained the army and citizens of the colonies was the direct product of Washington’s virtuous leadership.

The painting was an immediate hit with the public. More than 50,000 people visited the New York exhibit and even more viewed it when it moved on to Washington, DC, where it was placed in the rotunda of the nation’s capital. (9) It was viewed as a form of patriotic art throughout the duration of the 19th century. During the Civil War, both the North and the South highly regarded the painting. For individuals from the North, they used the image because it contained a black person to show that was one of the reasons why they were fighting, while individuals from the South connected with the theme of independence and liberty (10). It has continued to prove popular among the masses because it suggests the idea that Americans have strong ideals regarding liberty and freedom and are willing to work together in stark circumstances to fight for those beliefs. This aligns with Leutze’s goal in the painting. Leutze came to America as an immigrant and returned enamored with democracy and democratic principles; he believed the American Revolution could serve as the model revolution for Germany, which faced a potential revolution in 1848. As he was working on the composition, he initially envisioned brighter and more triumphant colors. When the revolution failed, the coloration changed and the goal of the painting was to demonstrate “determination and struggle to overcome oppression—the heroic quest.” (11) Leutze’s work resonated with most Americans, but some took great issue with both the content and the vision that Leutze had for his work.

Many people have not shared Leutze's vision for this seminal moment in American history. Larry Rivers’ Washington Crossing the Delaware is an artistic critical response to Leutze’s source piece. In the piece, Larry Rivers uses his style of painting, charcoal drawing and rag wiping, to create a scene that loosely mirrors the event depicted in Leutze version. Rivers wanted to create the “most controversial painting ever.” (12) Rivers’ had some observations to make about Leutze’s version:

The last painting that dealt with George [Leutze’s Delaware] and the rebels is hanging at the Met and was painted by a coarse German nineteenth-century academician who really loved Napoleon more than anyone and thought crossing a river on a late December afternoon was just another excuse for a general to assume a heroic, slightly tragic pose....What could have inspired him I'll never know. What I saw in the crossing was quite different. I saw the moment as nerve-wracking and uncomfortable. I couldn't picture anyone getting into a chilly river around Christmas time with anything resembling hand on-chest heroics. (13)

As a result of Rivers’ unfavorable view, he makes some interesting choices in white-washing and blurring some of the key figures involved in the actual crossing. Rivers has gone in a completely different direction with his portrayal of Washington, placing him in a “troubled area” and is considered by one critic to “mock bravura gestures” made by Washington in the original. (14) Rivers’ piece undercuts Leutze’s narrative of Washington’s brave leadership and questions an iconic moment in American history. (See Appendix for a link to the Rivers’ version of the moment)

Rivers’ Washington Crossing the Delaware induced others to rethink Leutze’s work. Frank O’Hara decided he would respond to Rivers’ and Leutze’s work in the form of a poem. This creates a similar image text pair to what we studied in seminar. O’Hara’s poem, “On Seeing Larry Rivers’ Washington Crossing the Delaware,” O’Hara recognizes the nature of Rivers’ efforts to explore the layers of meaning that are created in the Leutze version by adding even more layers of meaning. The title suggests the framing that both Leutze and Rivers engage in around a moment that may possibly be fictional or overdramatized by noting that he was seeing another form of the work in a museum. (15) (See Appendix for a link to O’Hara’s poem) O’Hara’s lines go further to frame what the moment might have actually been like when he writes: “Now that our hero has come back to us/ in his white pants and we know his nose/ trembling like a flag under fire/we see the calm cold river is supporting/ our forces, the beautiful history. (16) These lines are borderline irreverent to the popular image that Leutze’s work has engrained in the minds of many. Interesting enough, O’Hara’s depiction in his poem may more accurately portray what actually happened than Leutze’s paintin

Another contemporary manifestation of George Washington Crossing the Delaware is Robert Colescott’s painting titled George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware (See the link in the Appendix to view the painting). In the painting, Colescott takes an “easily recognizable masterpiece” and uses it to consider other issues. In depicting George Washington Carver, the painter mimics George Washington in the original Leutze piece: he is the tallest and most commanding figure, standing in the same stance, facing forward towards a goal, and dressed in a similar fashion. This projects him as a hero in the boat, an important individual surrounded by stereotypes. (17) Some critics argue that Colescott was trying to show the lack of real black faces in art and American history through exaggeration and the exploration of the roles of blacks in light of slavery. (18) This adds a new dimension to Leutze’s work. Just as Leutze relied on stereotypes to create unity by representing many of the stereotypical lifestyles that existed in the colonies, Colescott takes that idea and makes it subversive by questioning the roles that blacks had after slavery. George Washington and George Washington Carver share similar names and placement in each painting. Colescott elevates Carver to a similar mythical proportion as Washington, but it is hard to determine why. Colescott’s piece is controversial. Right in the middle of the piece, there appears to be a female figure performing a sex act on another male. The piece is not appropriate for middle school students, but it may warrant further exploration in a setting with older students. The Problem We All Live With by Norman Rockwell

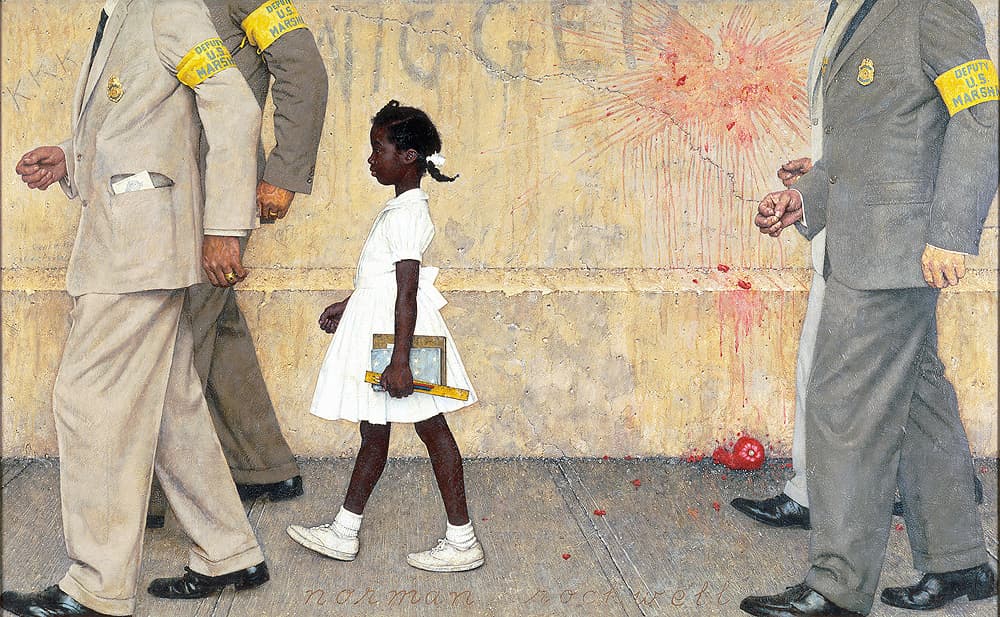

The Problem We All Live With by Norman Rockwell (19)

Norman Rockwell created the painting The Problem We All Live With to function as a centerfold in the January 1964 edition of Look Magazine. In the piece, Rockwell depicts Ruby Bridges as marshals walk her into a public school in New Orleans as a result of a desegregation order. (20) The action that is depicted in the piece occurred almost four years before the piece was made. Ruby Bridges entered the all-white William Frantz Elementary School on November 14, 1960. On that first day of school, besides being jeered at outside of the school, white parents entered the school to remove their children from the school. Few children remained in the school. Only one teacher was willing to teach young Ruby. Daily crowds continued to assemble to taunt Ruby and instill fear into her, going so far as to threaten her, saying that they would poison her, or building a small coffin and putting a black doll inside of it. (21) It is interesting to note that a four-year gap exists between this event and Rockwell’s depiction of the event. It leads one to wonder if he felt compelled when it occurred, if he thought that it was timely given other events related to the civil rights movement, or if enough time had elapsed that it became a safe topic to address related to civil rights and still project a sort of edginess in subject matter.

The Problem We All Live With does not shy away from controversial choices. The choices that Rockwell make in composition invite the viewer to think deeply about the loaded nature of this particular moment in history. Faintly inscribed in the wall that Ruby is walking past is the word NIGGER. The connotation of the word would weigh heavily on the viewer in any context, but it is especially poignant because it is directed at such a young girl. Dressed in a white dress, Ruby innocently marches on between commanding adult subjects. Color choices play a role in creating a powerful dynamic in the piece. The red of the tomato on the ground and smeared down the wall and the yellow of the armbands demonstrate the power that outside adult influences had on Ruby. Ruby narrowly avoiding being soiled by the dangers presented by jeering onlookers. Red and yellow historically represent colors associated with power and revolution. Red was the color of the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 and of the Chinese Revolution of 1949, and later of the Cultural Revolution: red was the color of Communist Parties. The goal of many whites who wanted to bar Ruby from entering the school was to make her feel intimidated or powerless because she represented a break in common segregated society that had been created in the South. Bridges actions were revolutionary, so Rockwell’s color choices are appropriate. Rockwell also makes a careful decision to depict Ruby facing forward with her head held high. She is also dressed in white, which creates the image of purity especially since she was wearing plaid the day of the actual event. This suggests that the onlookers have failed in their efforts to intimidate Ruby, a symbol of purity and innocence. It is also interesting to note Rockwell’s choice to “ .” (22) Given that this was created at the height of the civil rights movement, this decision goes beyond a tepid critique of the treatment that Ruby and other students received while trying to integrate all-white facilities and supports the revolutionary nature of Bridges’ actions.

This work had come not too long after Rockwell ended his contract with the Saturday Evening Post in order to express more political themes; Look allowed him a platform to create work that expressed some of his more progressive thoughts. (23) Despite Rockwell’s attempts to be progressive, some critics argue that when viewed with a contemporary lens that this piece falls short in some respects. In the text Normal Rockwell: The Underside of Innocence, Richard Halpern makes the following argument:

How does the treatment of Ruby Bridges by the millions of (mostly white) readers of Look differ from that of the New Orleans mob on November 14, 1960? The latter group views her with anger and contempt, the former with pity or admiration. But she is in any case a spectacle for the white gaze-- a specimen… By memorializing her, Rockwell has also frozen her in that traumatic moment of shame and fear. He has made her into the object of a liberal voyeurism. (24)

This argument is interesting and could lead to classroom conversations that will induce students to grapple with thematic matters associated with the work. It is hoped that students come to question whether or not the composition portrays Ruby in a manner that is triumphant or in a manner that robs her experience of power and dignity.

Considering Halpern’s argument about the depiction of Bridges in The Problem We All Live With, it would be an unfair characterization of Rockwell to not address the evolution of his career and his efforts to create work that is socially conscious and progressive for his time. In considering Rockwell the artist, it is important to note that his work was censored while he worked for the Saturday Evening Post; it has been suggested that this may have prevented him from tackling issues that aligned more closely with his beliefs. (25) Response to The Problem We All Live With was mixed from readers of Look; some readers were not used to seeing direct social commentary from an artist they thought they knew. This new direction in Rockwell’s career made it critical for the Norman Rockwell Museum to make this piece their first acquisition. (26) Early in Rockwell’s career, he tackled issues of race by ignoring them. In an exhibit of Rockwell’s work in Los Angeles in 1989, a critic noted how Woman Fallen from Horse (1930s) and Boy in a Dining Car (1946) show well-to-do whites being attended by blacks. (27) This secondary function that blacks played in the pieces reveals a sense of powerlessness and subservience that could be argued reflected society at the time, but it is interesting to note how The Problem We All Live With (1964) and even later New Kids in the Neighborhood (1967) place young black children at the center of the action rather than as observers of the action. (28) Ruby is clearly the subject of the painting, and the marshals are so insignificant that they do not have to be completely present in the scene. This change in approach and depiction of blacks cannot be underestimated and demonstrates a significant shift in Rockwell’s approach to race.

In considering Rockwell’s motives in the composition, it is also important to consider an argument made by Rockwell’s granddaughter. She argues that her grandfather breaks the safe and wholesome stereotype that many have of his work by using some of the most offensive racial language and imagery of the time by having NIGGER and KKK scrawled prominently in the middle of the text. She continues to argue that Rockwell created a composition that suggests Ruby represents the hope and promise for black children and points out a small detail that is easy to miss in the composition. He paints “a tiny heart with ‘MP + NR’-- to counterbalance the hate depicted in the scene.” (29) The MP stands for Molly Punderson Rockwell, Rockwell’s spouse. This is an interesting juxtaposition to consider; why would a white illustrator include an image of erotic love in a scene that is so hostile? Rockwell’s granddaughter may have a slight bias in addressing the works of her grandfather, but I do think it is worthwhile to consider her interpretation of her grandfather’s work as a way to further engage students and build their interpretative skills.

It is also worthy to consider the contemporary applications and responses to The Problem We All Live With. During President Obama’s first term, the painting was installed right outside of the West Wing in the White House. Ruby Bridges was invited to speak briefly with President Obama; he remarked, “I think it’s fair to say that if it hadn’t been for you guys [individuals like Bridges], I might not be here, and we might not be looking at this together.” (30) Many people criticized President Obama for not doing enough to send a stronger message on race, especially in light of him being the first African American president. For some, the choice to hang The Problem We All Live With was considered to be a safe choice to make a political statement on race; it was created by an iconic white artist, the event depicted was far removed from present times, and its installation was not followed by decisive actions by the administration to address institutions such as schools that may be on a path towards resegregating. (31) In this respect, critics of both Rockwell and Obama share similar criticism of both men; some argue they could have both been more innovative and provocative when it comes to addressing issues related to race.

Comments: