Teacher Prior Knowledge

Cell Cycle

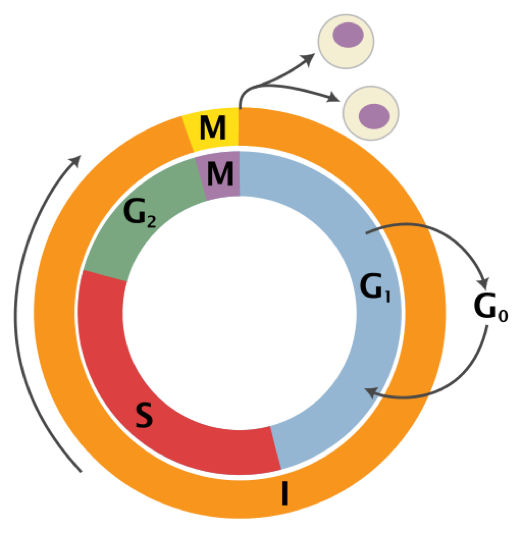

Figure 1. A basic representation of the cell cycle. Reproduced from Richard Wheeler (Zephyris) 2006.

The cell cycle is comprised of four main phases: G1, S, G2, and mitosis (Figure 1). During the G1 and G2 phases a cell’s growth and maintenance of homeostasis takes place. The S, or synthesis phase, encompasses the process of DNA replication. Mitosis is the cell’s process for cell division into two identical daughter cells. The length of time spent in each phase varies. The length of G1 can fluctuate greatly depending upon the cell but generally lasts for ten hours; S phase is consistently nine hours in length; G2 is approximately four hours, and mitosis approximately one hour.4 The majority of a cell’s life is comprised in G1, S, and G2 phases, collectively known as interphase. This accounts for 90% of a cell’s life at which time DNA, RNA, proteins, and other biological molecules are synthesized.5 Not all cells move through the cell cycle at the same time and rate; cells grow and divide asynchronously. In a given population of mammalian cells, 40% are in G1 phase, 40% in S phase, and 20% in G2 and mitosis phases (these are typical fractions).6 Cell division encompasses only a small fraction of the entire cell cycle.

Signal checkpoints are encountered prior to a cell progressing from one stage to the next. However, not all cells travel along the traditional cell cycle pathway; some move from G1 to G0 where they exit the cell cycle and do not divide (refer to Figure 1). The decision to either commit a cell towards a mitotic pathway or to an alternative arrested G0 stage is made in the G1 phase of the cell cycle.7 It is at the restriction point, or start location, that cells must evaluate both external environmental signals, such as available nutrients, and internal signals, such as cell size, to determine whether to commit to mitosis, differentiation, or stationary phase.8 If the conditions are favorable, the cell will continue through the remainder of the cell cycle, otherwise the cell will either temporarily or permanently exit the cell cycle. In unfavorable conditions—such as depletion of growth factors, lack of nutrients, or cell crowding—cells may enter G0 phase, a state of quiescence.9 Some cells remain quiescent for a short period of time while others such as nerve and muscle cells are permanently quiescent.10 These cells can be activated to proliferate if nutrients such as sugars, salts, vitamins, and essential amino acids needed for their growth become available.11 Temporary quiescence generally occurs between two successive cell cycles due to mitosis having depleted necessary requirements, such as size, for cells to immediately begin another cycle.

Cells exposed to appropriate conditions are permitted to begin the cell cycle. It is in the G1, or Gap 1, phase that the cell begins to grow and complete normal cellular functions. Cell growth requires the synthesis of new proteins, controlled by signaling pathways in response to hormones, available nutrients, and extracellular growth factors.12 Checkpoints prohibit cells from continuing through the cell cycle if an appropriate size is not met. Cells almost double in size prior to mitosis, producing “balanced cell growth”.13 The cell cycle process will be halted at a specific checkpoint within G1 if the cell has not reached the critical minimum size.14 This is important because cells must create enough cytoplasm, proteins, organelles, and genetic material to create two viable daughter cells. This stage culminates when DNA synthesis is initiated by growth factors involved in a signal cascade.15

Following the first growth phase, cells enter into the synthesis, or S, phase. This stage is representative of DNA replication. It is imperative that the entry into S phase only occurs in cells that are committed to undergoing the entire cell division process.16 The replication of the entire genome is important in order for the cell to complete mitosis at the end of the cell cycle and ensure that each daughter cell receives one complete copy of the genetic code. DNA replication occurs when the complementary strands are disassociated by DNA polymerase, read at multiple replication forks, eventually creating two identical strands of DNA. For more information, please refer to “Student Prior Knowledge” section.

G2 phase is the second stage of growth in the cell cycle. This stage occurs for a relatively short time period between DNA synthesis and the beginning of mitosis. It is presumed that this time is used to produce the machinery required for the cell to complete mitosis.17 After cells depart from this stage, they will enter cell division. Mitosis is discussed in a later section.

Cell Cycle Regulation

Regulation of the cell cycle is designed around a series of signal checkpoints. The role of each checkpoint is to detect the failure of an early event, generate a signal, amplify and transmit the signal to another location, and inhibit the machinery of subsequent events.18 Prior to moving between phases, signals must determine whether a cell has reached a specific benchmark. These checkpoints monitor potential DNA damage and have the ability to arrest cells in G1 phase and G2 phase.19 The completion of DNA synthesis in S phase signals the process of mitosis to begin. Regulation of chromosomal alignment in metaphase of mitosis ensures that genetic material is evenly distributed between the two forming daughter cells. A checkpoint at the completion of mitosis monitors cells before entering into another round of the cell cycle and replicating the DNA again. Cyclin-dependent kinases are a class of proteins that are responsible for the signal regulations.20

Checkpoints are a way for the cell to periodically self-assess. For example, a cell’s ability to proliferate is determined in G1 by assessing available growth conditions. Cells that experience damage to the DNA in G1 will not be permitted to enter S phase until repairs have been made.21 However, if regulation control fails, apoptosis, programmed cell death, or genetic instability can result.22 Cancer is a potential outcome if a cell progresses through the cell cycle after regulation has failed. As stated in a previous section, the restriction point allows a cell to continue in G1 phase. Initiation at replication sites must be regulated to ensure that all of the chromosomal DNA is completely replicated, yet nothing is copied more than once.23 Cells that have not completed DNA replication or have experienced some type of damage to DNA during replication can become delayed in G2 because mitosis will only proceed once replication has been completed and damage has been repaired.24 It is evident that multiple checkpoints ensure DNA is copied correctly and the proper mechanisms are produced that would otherwise prevent the onset of cell division.

DNA structure

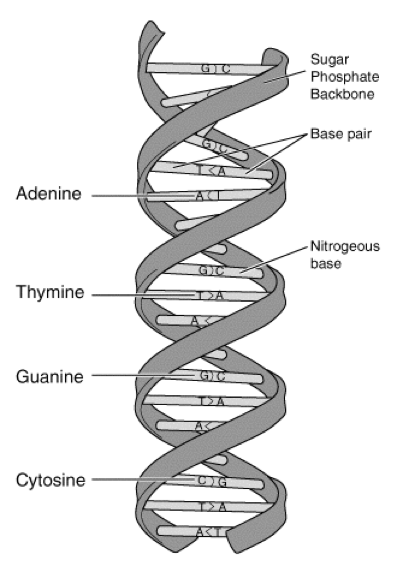

Figure 2. The structure of DNA. Courtesy of: http://www.genome.gov/Pages/Hyperion//DIR/VIP/Glossary/Illustration/base_pair.shtmlhttp://www.genome.gov/Pages/Hyperion//DIR/VIP/Glossary/Illustration/Images/dna.gif

Many of the molecular characteristics of DNA were discovered by Rosalind Franklin, but James Watson and Francis Crick were the first to describe its double helical structure. DNA is the genetic material encoding all living organisms. The molecule’s structure is that of a double helix, where two complementary strands are linked together by hydrogen bonds. It is a polymer, made up of a sequence of nucleotides, which are the monomers. Each nucleotide is comprised of a negatively charged phosphate, deoxyribose sugar, and nitrogenous base. There are four potential bases attached to the sugar-phosphate backbone: adenine, thymine, guanine, or cytosine. Guanine and adenine are both purines, while thymine and cytosine are pyrimidines. Purines bond with pyrimidines in a predictable fashion; adenine always bonds with thymine and guanine always bonds with cytosine.

Protein Synthesis

Cell growth during G1 and G2 stages consumes a large amount of energy, because it requires substantial protein synthesis, which is the most energy-consuming process in the cell.25 Every DNA molecule contains sections that code for proteins, regulatory molecules, and other expressed traits. These regions are known as genes. Less than two percent of a human’s entire genome encodes for proteins and the remainder is involved in gene regulation.26 It is not a simple process to build proteins from DNA. A segment of DNA must be transcribed, or rewritten, into RNA, transferred out of the nucleus, and translated into a protein. The protein must then be folded properly in order to complete its function. The central dogma of biology states that DNA is converted into RNA and then transformed into a protein.

DNA and RNA molecules share similarities in structure, yet possess key differences in their codes, influencing the necessity of both molecules in protein synthesis. DNA is a double-stranded molecule forming a helical structure, while RNA is often single stranded. The DNA code, as stated previously, is comprised of adenine, thymine, guanine, and cytosine nitrogenous bases. Each having a specific complement. RNA base pairs also contain adenine, guanine, and cytosine; yet DNA’s thymine is replaced by RNA’s uracil. This variance requires adenine to bond with uracil when transcribing from DNA to RNA. The sugar located in the backbone of these molecules also differs; DNA is made of deoxyribose, while RNA is made of ribose.

The process of biological transcription involves the conversion of the DNA sequence—stably stored in the double helix—into a transient RNA sequence. Complementary DNA strands must be temporarily separated in order to produce a messenger mRNA molecule. Genomic DNA is unable to travel outside of the nucleus; therefore, in order for the genetic information to travel to a ribosome in the cytoplasm to be expressed, the message on genomic DNA is copied into RNA. RNA polymerase is an enzyme that copies genes on a DNA strand. It recognizes a “promoter region” as the “start” signal for reading a gene.27 Initiation sites begin at the 5’ end of a DNA strand so replication forks are able to travel in the same direction as RNA polymerase, which is the protein responsible for copying the genes.28 When RNA polymerase reaches the end of the gene, a terminator region signals for the RNA polymerase to stop transcribing.29 The RNA molecule detaches from the DNA strand and the complementary DNA strands are reunited.

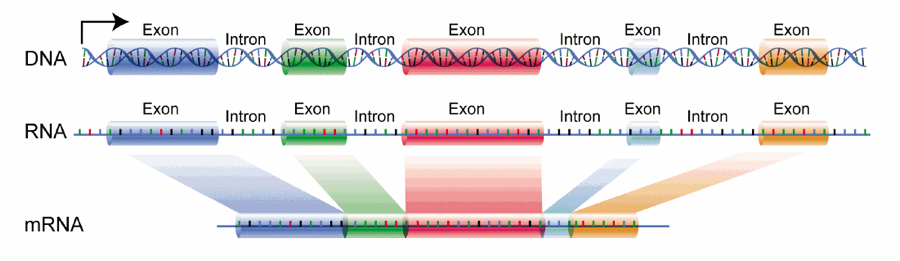

The single-stranded RNA molecule freely moves from the nucleus into the cell’s cytoplasm. The cell processes the RNA strand by excising the introns, adding a cap, and attaching a poly-A tail, which make the mRNA suitable for translation in the ribosome.30 This is in order to protect the genetic code when entering the cytoplasm from the nucleus. Introns are not needed because they do not code for the specific protein in question; the exon sections are spliced together to form the correct and continuous instructions for protein synthesis (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Excising introns from DNA/RNA and splicing exons in mRNA. Courtesy of: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/12/DNA_exons_introns.gif

Ribosomal production directly correlates to protein synthesis rates in most cells.31 This is explained by an increase in protein synthesis requiring more ribosomal sites. When messenger RNA binds to a ribosome, the sequence of nucleotides is used to direct the synthesis of a sequence of amino acids. This process is called translation – converting the genetic sequence into a functional amino acid sequence. The translational initiation pathway requires the binding and subsequent dissociation from the 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits, facilitated by initiation factors.32 The ribosome reads mRNA three nucleotides at a time, called a codon. There are sixty-one codons for twenty amino acids in addition to three stop codons making up the genetic code.33 The small ribosomal subunit identifies the first AUG, or start codon, and releases initiation factors for the large ribosomal subunit to join, creating an initiation complex.34 A tRNA molecule contains the complementary RNA sequence on one side, an anticodon, and the corresponding amino acid on the other. The tRNA is transferred to the ribosome and the new amino acid is added to the carboxyl end of the previous amino acid to form a peptide bond.35 As amino acids are continuously brought to the ribosome, a peptide bond forms between them and the tRNA molecule is then released and able to bring another amino acid to the ribosome. When the ribosome encounters a termination sequence, or stop codon, a release factor recognizes the codon that mimics tRNA.36 The amino acids bonded together by peptide bonds creates a polypeptide, which is also known as a protein once it has been fully formed and folded. Hundreds of thousands of different proteins exist in living organisms and are unique based upon the arrangement and length of amino acids.37

The structure and specific folding of a protein determines the function of the molecule. There are multiple types of proteins described by Tropp: catalytic proteins, structural proteins, transport proteins, receptor proteins, toxic proteins, and regulatory proteins which are pertinent to this unit because they are able to speed up or slow down biological processes such as cell cycle checkpoints.38

Gene Expression

Most cells in the human body, with the exception of red blood cells, contain the same genetic information, yet only specific genes are expressed by each type of cell.39 From the point of fertilization, stem cells differentiate to eventually make all of the cells within the body. As stem cells differentiate, many genes are “turned off” and specialized genes are “turned on”.40 Gene expression is regulated by either allowing or prohibiting transcription factors from binding to the DNA strand when producing messenger RNA.41

Mitosis

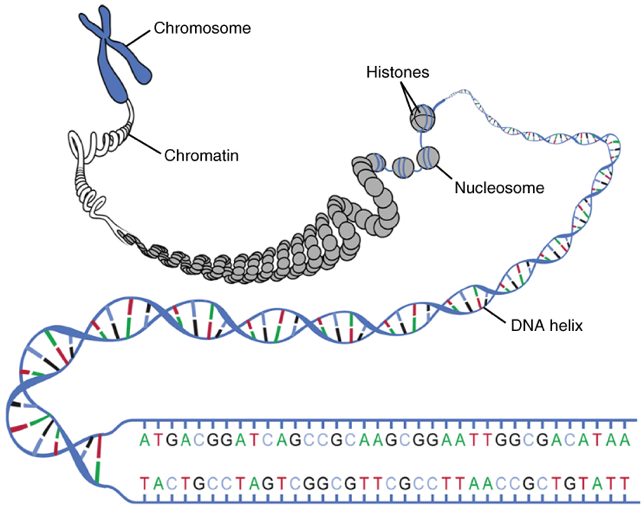

During the two growth periods and S phase, DNA remains uncoiled, in the form known as chromatin. The genetic material is copied by DNA replication in S phase. After interphase—which is comprised of G1, S, and G2 phase—is complete, the DNA double helix coils up around histone proteins, creating a condensed structure called a chromosome. The coiling of the replicated DNA will develop the iconic X-shaped structure. The centromere is the central region holding the sister chromatids together. During mitosis, the replicated DNA are separated to create two identical daughter cells.

Figure 4. Replicated chromosome structure uncoiled to make individual nitrogenous bases visible. Courtesy of OpenStax https://cnx.org/contents/FPtK1zmh@8.25:fEI3C8Ot@10/Preface

The chromosomes become visible as the nuclear envelope, surrounding the nucleus, begins to break down and DNA has condensed. Prophase is described as the beginning stage of mitosis. Evidence suggests that chromosomes begin condensing in S phase and reach complete condensation during anaphase.42 After the spindles have formed and begun to move to opposite sides of the cell and the nuclear envelope has disappeared, the chromosomes arrange themselves along the metaphase plate, located relatively on the central plane of the cell. Once the chromosomes are aligned in the middle and the spindle fibers are attached to the centromere, the cell is considered to be in metaphase, where meta- indicates the middle. A mitotic checkpoint ensures that segregation occurs correctly by delaying the completion of mitosis until all chromosomes have been properly attached to the mitotic spindle.43 The spindle fibers carefully pull, by shortening their length, the replicated chromosomes to opposite sides of the cell to ensure that each daughter cell receives only one copy of the chromosome. As chromosomes move towards opposing poles, the cell is said to have entered anaphase. Ana- is a prefix to indicate something that is “anti” or “against” and in this case the chromosomes are moving away from each other. As the chromosomes have segregated, the cell membrane begins to create a cleavage furrow and begins to pinch together. The nuclear envelope begins to redevelop around two separate nuclei. Telophase is the process by which the cell membrane pinches together and the nuclear envelop reforms. The last stage of mitosis, and the completion of the cell cycle, occurs when the two daughter cells have completely separated from each other, the nuclear envelope is intact, the chromosomes uncoil and are no longer are visible behind the membrane. Ideally two identical daughter cells have formed. There are incidences where the chromosomes do not separate properly during anaphase and create daughter cells with improper chromosome numbers.

Comments: