Background Content

Establishing A Genetic Model

Though humans had used the natural diversity of living organisms to their advantage, they knew little of the structures or biological processes responsible for the genetic variation within species. In 1866 Gregor Mendel proposed three laws of inheritance to explain the transmission of characteristics between successive generations of pea plants. He proposed that the interaction between alternate forms of each trait produced the variations observed in offspring of given organisms. The work of other scientists during the early years of the 20th century refined Mendel’s work and introduced modern terms such as genotype / phenotype, genes, alleles, and chromosomes into the developing field of genetics. Thomas Hunt Morgan worked with varying species of Drosophila (fruit flies) and proposed that genes resided on specific locations on the chromosomes located within the nucleus of the cell. Although Hunt’s work established a physical relationship between genes and chromosomes scientists did not yet fully understand the biochemistry of genetic structures, how genetic information was stored, or how genes were able to influence biochemical processes at the cellular level.

Understanding Genetic Structure

The discovery of the structure and composition of the DNA molecule (by Franklin, Crick, and Watson in 1952-1953) provided our first understanding of how genetic information is stored at the molecular level. Francis Crick expanded this understanding with his model of the manner in which molecules of mRNA and tRNA work (along with other structures in the cell) to translate genetic information into molecules (proteins, enzymes, hormones) that regulate bodily functions. From the earliest understandings of the molecular basis of genetic structures, scientists wondered if they could influence the biology of living organisms by manipulating the genetic codes stored within our DNA.

Genetic Modification

The discovery that yeasts and bacteria had endogenous mechanisms that allowed them to repair double stranded breaks in their DNA, provided the first clues that site specific targeting and modification of the genome was possible.9 Soon after that, genetic engineers began experimenting with an array of endonucleases and restriction enzymes that could recognize specific base pair sequences on an organism’s DNA. Once a specific site was located these enzymes could be used to cleave the DNA and introduce chromosomal modifications to an organism’s genetic structure. The resulting recombined organisms would be a transgenic species as it contained DNA from two (or more) differing sources. Recombinant DNA technology became a reality in 1972 when researchers used the restriction enzyme Eco-RI to insert genes encoding proteins into bacteria. The bacteria would become the first transgenic organism created by genetic engineers. In 1979 Genentech corporation used the technology to engineer a transgenic bacterium that produced the growth hormone somatostatin.10 Using the same technology companies soon learned to genetically modify plants to make them resistant to pathogens, since then the world has seen countless applications of the technology.

In the ensuing years, genetic engineers developed various technologies (such as Zinc Fingers, TALENS, and PCR) to increase the range of biogenetic engineering,11 their work was however, tedious, expensive, and time consuming: that was until CRISPR- Cas-9 revolutionized the industry 12 .

CRISPR Cas- 9 Technology

In 1987 researchers exploring the iap gene in the bacteria Escherichia coli reported the discovery of a series of 29 segments of RNA separated by short repeats.13 Analysis of the function of the array showed that it was a system created by the bacteria as part of an adaptive defense mechanism. Most bacteria seem to live in ever-changing environments where bacteria-specific genetic elements, (such as plasmids and phages), attempt to enter the cell and harness the cellular metabolism and molecular machinery to replicate themselves. As such, bacteria benefit from having a flexible and readily adaptive immune response to withstand such invaders. Rather than having a system of specific immune cells that are trained to recognize and degrade invading pathogens (like many eukaryotes), single-celled bacteria that survive an attack can then incorporate copies of a portion of the invader’s genome into what has become termed a CRISPR array. The name CRISPR-Cas-9 refers to the combined system of non-coding RNA sequences (spacers) and associated Cas proteins used to identify and cleave the genome of invading pathogens.

The CRISPR Cas-9 Array

The CRISPR array is a region on the genome of a bacteria (or archaebacteria) containing a Cluster of Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats 14 in association with a series of proteins known as the CRISPR Associated Proteins or simply Cas-9. The array is composed of short segments called spacers that contain the memorialized segments of the genome of invading organism separated by short segments (approximately 28-37 base pairs) of DNA.

The array is a kind of reference library that is used to alert the organism upon reinvasion by a phage or plasmid. CRISPR is an adaptive system as it can continually respond to its environment (by adding or removing spacers) during the bacterium’s lifetime. Many scientists consider CRISPR to be an example of Lamarckian (rather than Darwinian) evolution as it is a heritable adaptation developed during the lifetime of the organism rather than one that emerged in a population in response to selective environmental pressures.15

The System

The CRISPR system is composed of three phases: Spacer Acquisition, crRNA Processing, and Interference. It is important to note that there are three known systems (CRISPR- types I, II and III). The basic components of the systems are similar; however, there are variations in the number, function, and orientation of the Cas proteins.

Spacer Acquisition

When a genetic element (usually a phage or plasmid) invades a bacterium (or archaeal cell), two Cas proteins (Cas-1 and Cas-2) cleave the invading genome (either DNA or RNA depending on the invader) and sequester a short segment (a protospacer of approximately 32-38 base pairs [b.p.]) into the array along with a repeat. Every time an invasion occurs, the Cas proteins cleave the foreign DNA and integrate a section of its genome (along with a repeat) into the array.16 It is important to note that the Cas proteins do not cut at random locations, rather they select sequences that are adjacent to specific sites on the invading genome. These sites are known as PAM (Protospacer Adjacent Motif) are not included in the spacers stored in the CRISPR array. When reinfection occurs, the bacteria will use the PAM sequences to tell the difference between the DNA of an invader and the corresponding protospacer of its CRISPR array: in this way the bacteria will attack the invading entity and not itself.

crRNA Processing

To create the defense mechanism the bacteria transcribes the CRISPR array (protospacers and repeats) into a strand of mRNA (the crRNA). In the type-I CRISPR system this crRNA strand is cut into sections each of which contains a segment of an invader’s genome and a repeat. In this system the repeat is in the form of a loop. Each of these crRNA molecules is then merged with a Cas protein forming a complex that will remain in the cell. The various complexes (each with a different segment of foreign DNA) function much like a group of sentinels that will be activated if reinfection by one of the “known” invaders occurs.

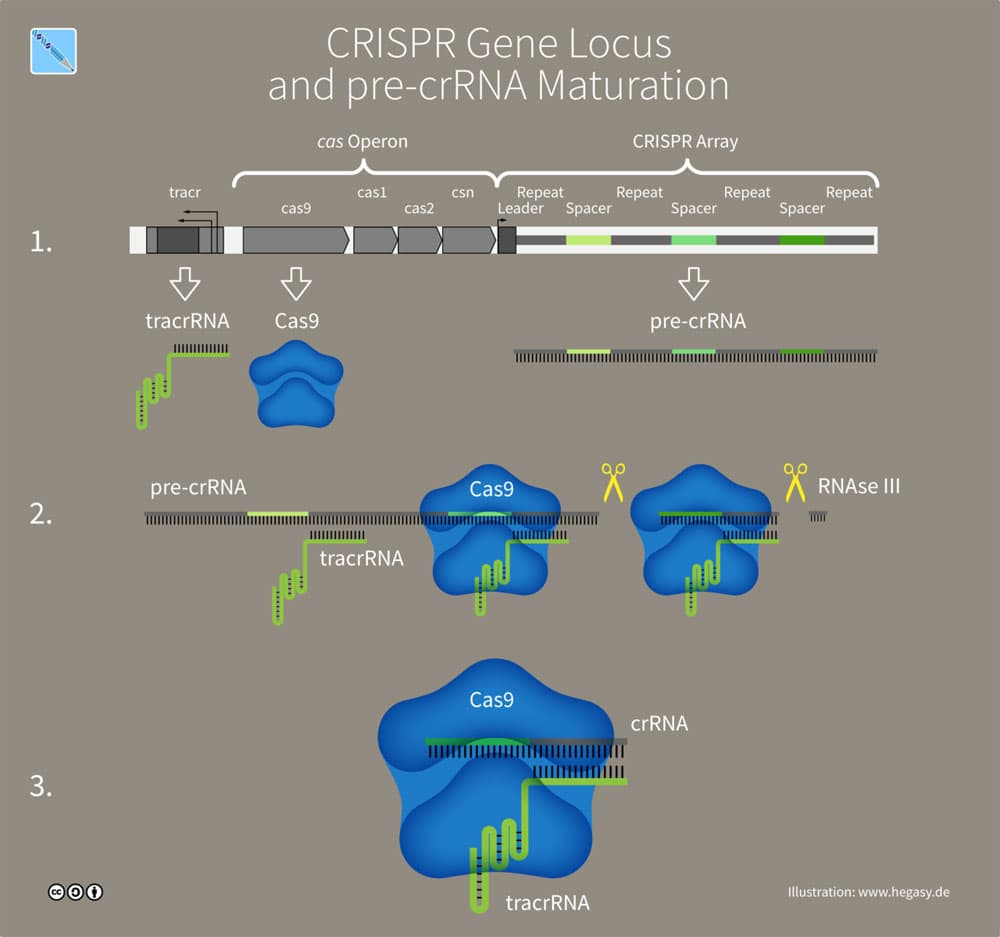

In the type-II CRISPR system a second sequence of RNA (the trans activating, or tracRNA) is bound to each repeat. Each protospacer in this system is therefore bound to two segments of RNA (crRNA: tracRNA) which are called the guide RNAs. After the array is transcribed, Cas proteins (Cas-9 and RNase-III), cut the (crRNA: tracRNA) segments into smaller sections, each containing the two segments of RNA repeats and a spacer. Once again, the segments are each merged with Cas proteins forming the complexes that will defend against reinfection (see Figure 1).

Figure 1:CRISPR-Cas-9 Array

Interference

The Cas-protein complexes formed during the crRNA processing are activated whenever a known invader reenters the cell. When this happens, the Cas complexes will recognize the DNA sequence and the corresponding PAM site on the genome; which will identify the genome as foreign genetic material. The protospacer sequence will then bond (through complementary base pairing) with the foreign DNA. Once this occurs one of a series of CASCADE (CRISPR-Associated Complex for Antiviral Defense) proteins will deactivate the invading genome. In type-I systems the CASCADE protein is a Cas-3 protein that cleaves the DNA into small inactive pieces. In type - II systems, the CASCADE protein is the Cas-9 protein which uses various enzymes to make a double strand break in the DNA.

Editing and Repair

Once a double strand break (DSB) occurs, the cell will attempt to repair the break using one of two mechanisms: Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) or Homology Directed Joining (HDJ).

In the former mechanism the cell will join the ends of the DNA together using a ligase enzyme. This method is error prone as the process can create insertions or deletions of the gene sequences leading to a frame shift that will lead to a variety of negative biochemical consequences.17 The second method of correcting a double stranded break is to use homology directed repair. Cells have traditionally used this repair pathway (during mitosis) when a sister chromatid is nearby, and the homologous strand can be used as a template to repair a break.

Frame Shifts in DNA

Our DNA contains the genetic code that directs the synthesis of the countless chemical compounds that control the body’s biological processes. Each of our body’s approximately 20,000 18 genes is composed of a long sequence of precisely ordered nucleotides. The sequence of nucleotides is the code for amino acids which (when linked together) form the vast array of biochemicals that control every aspect of our existence. The process of transcription, to translation and synthesis of proteins is often referred to as the “central dogma of molecular biology”.19 The process begins when a molecule of mRNA makes a complimentary copy of a given sequence of nucleotides. The strand of mRNA moves into the cytoplasm where it interacts with ribosomes which read the sequence of nucleotides (three nucleotides at a time). Each set of three nucleotides (known as codons) correspond to a given amino acid (according to the underlying genetic code). It is critical that the sequence of nucleotides be read in the exact order specified by the DNA code. Changes to the code as a result of single point mutations, or insertions / deletions (indels) create frame shifts which alter the sequence of base pairs and the resulting chain of amino acids.

Applications of CRISPR Cas-9

The ability of the CRISPR system to achieve targeted editing of a precise location in a genome provides a highly efficient, relatively inexpensive, and accurate method of altering an organism’s genes. While the constraints of existing genetic technologies limited the range and efficacy of genetic engineering, the advent of CRISPR technology has given researchers in various fields a reliable tool to solve long standing problems in agriculture, medical research, disease prevention, and ecosystem restoration. Researchers are now able to direct the Cas proteins to cleave a specific region of an organism’s genome. They can also provide the cell with the genetic information it will use to repair its DNA. In this manner new genetic material can be introduced into the cell’s genome.20

Benefits of CRISPR Cas-9 Technology

In agriculture, CRISPR “has become a simple, most user friendly and efficient, precise genome editing tool for development of genetically edited crops”.21 The system can be used to modify plant genomes so that they become more resistant to viruses, bacterial pathogens, and pests. This should make farming less toxic as it would reduce or eliminate the need for pesticide use.

In addition to conferring resistance, researchers have used the technology to engineer mutations that increase size, nutritional value, ease of cultivation, and other desirable traits which would increase crop yields throughout the world.22 The technology also provides novel approaches to address plant, animal and human diseases that have proven difficult to treat or cure. Recently scientists proposed a method of excising the HIV virus from cells as shown in a mouse model.23

It is also proposed as a method for editing genes responsible for genetic diseases such as sickle cell anemia, forms of muscular dystrophy, beta thalassemia,24 as well as using it to develop genetic therapies in cancer research.25

Gene Drive Technology

Although genetic engineers have developed the ability to alter the genomes of organisms that transmit diseases, they have never been able to efficiently insert a mutant gene into an entire population to address a disease problem. If they inserted a mutant gene into an insect (or rodent), the gene (according to the laws of Mendelian inheritance) would have at most a 50% chance of being expressed.26 Over time the mutation would fade into the larger gene pool and perhaps disappear. This is not the case for a gene drive, which could be used to forcibly introduce a mutation into a target population.

A gene drive is composed of a gene that has been engineered to achieve a given result (e.g., decreased reproduction, reduced ability to transmit a pathogen, or limited life span), along with a mechanism (for example a CRISPR complex) that will drive the gene into the genome of all members of a given population. Gene drives can be defined as systems of biased inheritance in which the ability of a genetic element to pass from a parent to its offspring through sexual reproduction is enhanced.27

When organism’s mate, the offspring receive one chromosome from each parent. However, when one parent carries a gene drive mutation, one of the offspring’s two chromosomes will have the gene drive, the other chromosome (from the wild type) will not. When the chromosomes interact, the CRISPR complex will cause a double stranded break in the (wild type) chromosome. When the cell initiates its repair, it will use the mutated gene as a template: thus, creating two mutated chromosomes. This process will continue every time mating occurs thus increasing the number of organisms carrying two mutated genes. In subsequent generations, the percentage of organisms carrying the mutated gene will increase, and (depending on the rate at which the organism reproduces) all members of the species will eventually carry the mutant gene.

It is compelling to consider the possibilities that the gene drives offer our species given our ability to create precise mutations in the genomes of any living organism. The applications for this technology are wide ranging as it can be used in theory, to control organisms that transmit diseases to human populations, control invasive species that disrupt ecosystems, and eliminate pests that impact agricultural production.28

Risks and Unintended Consequences

Gene drives hold great promise in our efforts to improve the quality of life for our species. However, it is incumbent on us, to realize that these technologies can pose grave risks to the Earth and all the species that live on it. Before these engineered organisms are released substantial research should inform a body of public policy that will safeguard our ecosystems and other living organisms. Gene drives are most impressive in their (projected) ability to eradicate organisms that transmit diseases that cause millions of deaths each year. However, there is no guarantee that a mutated gene will remain in the target organism and will not migrate into another species (horizontal gene transfer),29 or that the gene will not mutate in response to selective pressure, or that it will occasion the rise of other more virulent pathogens.30 The ongoing loss of lives due to mosquito borne illnesses will likely motivate some in our society to vigorously advocate for the deployment of a gene drive somewhere on the planet, despite possible risks. While the use of the technology is a likely inevitability it is critical that we realize that

Continuous evaluation and assessment of the social, environmental, legal, and ethical considerations of gene drives will be needed to develop this technology responsibly and adapt research and governance to the field’s complex and emerging challenges.30

The CRISPR-Cas-9 system poses different but an equally dangerous set of risks as it can also occasion unintended mutations. While researchers can use the system to target a specific site on a genome, there is the possibility that the complex will act mistakenly on other non-target sites in the genome and occasion off target double stranded breaks.32 The resulting mutations can endanger the organism, or (if the target site is seriously affected) cause its death. CRISPR poses another set of ethical problems as it can be used to modify somatic and germline cells.

Ethical Concerns

Editing germ line cells is a highly controversial application of CRISPR technology as it has the potential to alter human patterns of heredity. While the use of this technology may provide alternatives to parents with no other option through which they can save a child,33 the moral and ethical ramifications of embryonic engineering are quite troubling. Moreover, such technologies (when they become widely available) will cost more than most can afford. What will happen when poorer citizens need such technology? What will happen when only the richer nations have such access?

Socio-Political Implications

It is important to note that new gene editing technologies (such as CRISPR) differ from traditional methods of modifying an organism’s genetic structure. Those techniques rely on the replacement of an organism’s genes with those from another: techniques such as CRISPR alter the organisms own genotype and are therefore not considered a “trans-genetic modification”.34 This is an important distinction as the United States federal government has recently listed regulations that may exempt new gene editing technologies from existing regulations on GMO’s.35 While these regulations hold for American interests, such is not the case internationally where a debate as to classification of new genetically edited organisms is ongoing.36 This is a serious consideration given the need for policies that will safeguard all nations.

Although the potential benefits of new gene editing technologies are very promising, there are a wide range of potential risks that have yet to be fully articulated and explored. Gene drives are at the forefront of research efforts given the toll that mosquito borne diseases have on mankind. Recent outbreaks of Zika and Dengue fever, along with the historic death toll of malaria outbreaks, have increased interest in gene drives as a way to eradicate these mosquito-borne diseases. While we have already released genetically altered organisms into our ecosystems, the intentional eradication of an entire species raises profound environmental, ecological, and ethical considerations.37 All experts agree that an extensive amount of discussion within national and international forums must take place before such technologies are deployed;38 however, the discourse on the safety and security of these technologies needs to include a diversity of voices (from developed and developing nations). This is critically important in the case of the proposed deployment of gene drives as they will likely be used in underdeveloped nations that are traditionally overlooked when the interests of developed nations are at stake.39

Comments: