Content Background

As an avid fan of shows like Planet Earth, Blue Planet, and Night on Earth, I enjoy immersing myself into a world of majestic landscapes, colorful animals, and towering trees. Viewers of these mesmerizing shows enjoy the biodiversity highlighted in the program. We love to watch Birds of Paradise dancing, flamboyantly displaying their feathers to attract mates, or pods of Orcas working collaboratively to hunt seals displaying their inherent skill to communicate and work cooperatively. However, amid the beautiful scenery, just a camera span away, is the sad reality of deforestation and urbanization. As humans we at times neglect to recognize that in order to have the beautiful biodiverse world earth has provided us, we must protect nature and preserve biodiversity. In a way, it seems incongruous to say, “I support the preservation of nature” while building a multibillion-dollar shopping mall / luxury condo next to a once pristine habitat.

This curriculum unit examines one driver for biodiversity decline across the globe – land-use change. It will explore how land-use change leads to other issues impacting human health, especially the emergence of infectious disease. Through the exploration of these key issues, teachers and their students will understand that the problems which exist are not the result of a single event in history, nor is the solution to the problems one policy change. The problems, and their solutions just like our earth, are diverse, complex, and a multi-faceted solution might be the only way to prevent the biodiversity losses in the Anthropocene.

Land-Use Practice and Emerging Infectious Diseases

Humans know that deforestation, destruction of habitat, global climate change, and decrease of the earth’s biodiversity have greatly increased in the last 200 years. Often, we are drivers of extinction for many organisms in our exploitation of earth’s resources. Elizabeth Kolbert’s book The Sixth Extinction, An Unnatural History narrates how humans, for example, drove the great auk to extinction by hunting the defenseless penguin-like birds until not one was left on the planet. She describes how rising temperatures, ocean acidification, deforestation, and increased runoff from agriculture have contributed to the decline of once pristine coral reefs.5 In effect, human activities, good or bad, often had larger effects on the ecosystem. This effect may be rapid, or may take time, but we are now living through an epoch of increased extinction rates caused primarily by us.

One driver for biodiversity decline is human demand for land. Patz et al. in “Unhealthy Landscapes: Policy Recommendations on Land-Use-Change (LUC) and Infectious Disease Emergence” list LUCs linked to infectious disease outbreaks and transmission of endemic infections. The list includes “agricultural encroachment, deforestations, road construction, dam building, irrigation, wetland modification, mining, expansion of urban environments, and coastal zone degradation.” In fact, the 2019 UN Report of Intergovernmental Science-Policy on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, states that 75% of land and 66% of marine environments have been impacted and altered by human activity.6

With increasing human population, a growing demand for land that can be cultivated and farmed follows. In 2019, Worldindata.org estimates that of the available habitable earth surface on our planet over 50% is used for agriculture, while 37% remains as forests, and 11% is a variety of shrubs.7 Though we would like to imagine that all agricultural lands are utilized for the purpose of feeding the human population, the sad reality is that much of the crops grown are for the purpose of livestock feed, with 23% of the 50% is used for the growing of crops.8 In essence, if we were truly growing food for humans to consume, we, perhaps, would solve the world malnutrition and hunger issues. Instead, most of the agriculture produced is for the purpose of feeding livestock which in turn has its own set of consequences on the earth’s climate as carbon dioxide levels continue to contribute to global climate change.9

Students in high school, know that the Amazon rainforest should be saved. But what many of them cannot fully articulate in their argument is why it should be saved. Like many countries struggling to balance agricultural and wild habitat land areas, even the Amazon is not immune to destruction and deforestation. Recognizing that the Amazon rainforest produces 20% of the world’s oxygen and has over 10 million species of plants, animals, and insects within its 2.6 million square miles, it is, nevertheless faced with many issues. Poor land-use practices in the Amazon led to practices that disrupted the Amazon’s rivers to produce hydropower. This one change in land-use creates barriers for aquatic species and interferes with fisheries that are depended upon by Amazon’s indigenous tribes. Illegal and unsustainable extraction of the Amazon’s resources like gold, trees, and aquatic species have damaged vast areas of the rainforest. In addition, with rising global temperature, the forest is less able to protect its many riches from dangerous droughts, and the inevitable forest fires. Beyond this problem, is the growing issue of converting dense forests for cattle ranching and grazing lands. Cattle ranching not only requires deforestation but pastures contribute to contamination of rivers and freshwater resources. Figure 1 below from Daniele Gidsicki shows one area of the Amazon where deforestation has occurred. Sadly, a scene like this is becoming more typical throughout Amazonia.10 Furthermore, carbon dioxide levels increase as more cattle are raised adding to the problem of global climate change and warming temperature.11 With increasing cattle farms, agricultural farms, and logging at industrial scales, run-offs to the richly diverse Amazon River are inevitable. If humans and our policy makers do not curb our enthusiasm for natural resources we may soon create dead zones (areas where little to no life exist) in an area once considered a Garden of Eden for its diversity of life.

Figure 1: Amazon deforestation

11,000 miles away, on the other side of our planet, a similar pattern of destruction is occurring. The Amazon’s problems with land-use change are mirrored in Southeast Asia. With booming populations and an economy reliant upon the production and sale of rubber, oil palm and logging, Malaysia, Indonesia, Borneo, and Sumatra threaten the species biodiversity of their country for economic growth. In Indonesia and Malaysia approximately 50% of the natural habitats have been converted to agriculture. Nearby, the islands of Borneo and Sumatra, where there are over 15,000 species and 50 completely unique ones, are also threatened by land-use practices. In this home of the Sumatran orangutan, rhino, pygmy elephants, and tigers, the rich biodiversity is exploited by illegal wildlife trading, deforestation and, once again, unsustainable agricultural practices. Here, deforestation is purposely done to raise palm-oil producing crops and coffee. So, the next time you enjoy that rich boldness of your Sumatran coffee beans, recognize that it is probably at the cost of habitats for rhinos, elephants, and tigers.12

The examples of the Amazon and islands in Southeast Asia are only two of many sites where humans have caused detrimental changes to the landscape. Through these cases, it is clear that humans not only have made an imprint on our planet, but have left a boot print smashed into the face of the earth. Battered and bruised, Earth continues to provide us with all of our needs; however, our continued demand for resources has also led to an unforeseen consequence – disease.

Emerging Pathogens

Patz et al. assert the link between the emergence and/or reemergence of zoonotic pathogens to anthropogenic modifications of previously wild habitats. Humans altered the natural environment causing a disruption in the host-parasite equilibrium. This change forced a kind of natural selection among the host or parasite. In essence, when an organism like a bat or a bird, which are reservoirs for some viruses, is forced to change its nesting place or food source, the strains of viruses within them are sometimes changed in order to take advantage of a new host (humans) in the new habitat.13

In a Nature article on “Global hotspots and the correlation to emerging zoonotic diseases,” Allen et al. assert that in areas like tropical rainforests where biodiversity is high there is an increased risk of emergence of infectious disease (EID). Allen et al explain that with greater biodiversity, the greater and deeper the pool for EID hosts. If there is an increase in interactions with these hosts, it is probable that an EID may arise when humans come into contact with an infected intermediary host or the reservoir for the EID itself.14 Rebekah White et al., confirm the work of Patz and Allen adding that reservoirs for EIDs are bats. Some species of bats can carry 200 different viruses, bacteria, and fungi. Within some bat species, RNA viruses are likely to emerge because they are particularly good at adapting to their new environment, and can rapidly replicate and mutate in a new host species. White et al. continue and state that as land-use changes occur, the higher the chance of a new virus successfully emerging. Unfortunately, the connection to our current Covid-19 pandemic is ongoing and needs further study. Research is needed to help scientists predict when, how, and where a new zoonotic disease occurrence might happen. This work is difficult and complex requiring cooperation and agreement from multiple countries.15

It is important to note before entering a discussion into zoonotic diseases and emerging infectious diseases that the term “emerging disease” is recognized as being broad and subjective. The term is defined as “infectious disease with increased incidence in the past two decades or threatened to increase in the near future.”16 In actuality, emergence can mean the emergence of new diseases like Covid-19, new strains of a known virus (influenza), the re-emergence of once eradicated diseases (smallpox), and once-rare diseases returning in prevalence (Ebola). In a nutshell, the word “emergence” could mean many things, and the word “threatens” invokes both a sense of something ominous and something lurking to hurt humans.17 The CDC list of emerging pathogens is frightening. Included in this nefarious list is Ebola Virus, Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome, H1N1 Influenza virus, Zika virus, SARS, and today’s SARS-Covid-2.18 This curriculum unit will highlight three viruses that link land-use change to emerging diseases: Nipah, SARS, and SARS-Coronavirus 2.

Nipah Virus

The first example of Nipah virus in Southeast Asia arose because of a planned controlled fire to change a once wild forest to agricultural land. Essentially, the Indonesian forest fire was set to clear the land to make way for farms. Lam and Chua report in Clinical Infectious Diseases that the outbreak of Nipah virus in Malaysia can be traced to the Island Flying Fox, a type of fruit bat.19 The forest fire forced the resident fruit bats to flee and take up residence in an area with domesticated pigs in nearby Malaysian orchards. The bats feasted on the fruit trees, and the fruit remains were consumed by pigs whose meat became tainted. Humans eventually slaughtered the pigs and subsequently made some humans severely ill with fever, vomiting, headaches, and brain inflammation. The inflammation of the brain led doctors to initially believe that the virus disease affecting pig farmers was Japanese Encephalitis (JE), but when a vaccine did not work to reduce the number of farmers being affected, JE was reasoned out. Because it was found that the intermediate hosts were pigs, more than a million pigs were culled to stop the spread of the virus. When it was discovered that fruit bats urinating on the pigs’ food was the cause of pig infections with Nipah virus, changes were made to the pig farms to prevent food sources being too close to orchards where the flying foxes were prevalent. Another change in policy was that pig farms could not be developed near fruit trees.20 Other locations where Nipah Virus cases emerged included Bangladesh and India. Cases in these countries did not come from fruit bats directly, but from person to person contact with already infected humans.21

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

A second example of zoonotic infectious disease is the development and emergence of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). SARS is relevant to study because of its closeness to the current novel Coronavirus pandemic. There are seven different types of coronaviruses, but not all of them are circulating in human populations. Some coronaviruses contribute to the common cold, whereas others can cause more severe symptoms in humans including SARS and the current SARS-Covid-2 infections. Three coronaviruses show zoonotic behavior, which have a seemingly common source in bat populations. Virologist Shi Zenghli dubbed the “bat-woman of China” and her team spent a decade tracking the source for SARS virus and found that bats (horseshoe bats) are the natural reservoirs for SARS along with other viruses.22 Their work led them to caves littered with guano and which “stunk like hell.”23 Zenghli declared that the combination of bat species and the variety of viruses that thrive within bats were a dangerous combination. This dangerous combination of viruses is especially impactful when farms growing food were close to the caves teeming with bats.

The SARS outbreak, unlike today’s SARS-Cov-2 pandemic, came from bats with the help of intermediary animal hosts: civets. (Figure 2 below) Civets are nocturnal omnivores that feed on rats and other rodents, arthropods, and fruit. The capture and sale of civet meat at wild game markets in China were traced as the initial source of SARS when humans consumed virus tainted meat. This new disease was different from Nipah Virus because it seemed very similar to the flu with patients coughing and showing signs of a fever. Patients with SARS had shortness of breath and described feeling like their lungs were drowning in fluid. Unlike SARS-CoV-2 those infected showed symptoms after 24-36h and lacked asymptomatic cases.24 Those infected through respiratory droplets and water fecal droplets were able to spread the virus.

Figure 2: Juvenile palm-oil civet 25

This SARS epidemic was responsible for more than 800 deaths and over 8000 cases during 2002-2003. 26 Unlike today’s COVID-19 pandemic, SARS was never labelled as a pandemic, though by the end of its run, there were over 8000 cases across 32 countries and 773 of the inflicted died from SARS. Simon Watt in 2012 questioned, “The 2003 SARS outbreak wrought global havoc, but quickly faded. Will we be so lucky when the next pandemic strikes?” He predicts in his London Times article, “Next time we won’t be so lucky. And we will have a next time.”27 Clearly his 2012 question has been answered with today’s global SARS Covid-2 pandemic.

SARS-Coronavirus-2

This next discussion of SARS-Coronavirus-2 will focus on the anatomy and physiology associated with SARS-Covid-2. Since my students will focus on SARS-Covid-2 the unit will serve as a survey of physiological systems affected by SARS-Covid-2. Just like SARS-Covid-1, SARS-Covid-2 is a zoonotic disease that likely jumped from a fruit bat to an intermediary host and then humans. As of June 22, 2020, there has not been one declared intermediate host of SARS-Covid-2. To date, that possible list includes pangolins, rodents, livestock, and dogs. Our understanding of the origins of SARS-Covid-2 is ongoing, and data continue to pile in day by day. At the writing of this unit in July 15, 2020, the United States led the world in the number of cases followed by Brazil and India. To understand how “deadly” the virus is students will need to know the Case Fatality Rate (CFR), given by the equation: # of deaths / total # cases. To compare, SARS-1 has a CFR of 10%, while the SARS-Covid-2 has a rate 3.7%.28 Why is the case fatality rate so low for SARS-Covid-2 and why is it important for students to understand? The low CFR for SARS-Covid-2 is in part because of the number of unknown COVID carriers who are asymptomatic. Asymptomatic patients therefore do not get tested or rarely get tested thereby reducing the total number of cases and lowering the CFR.

Similar to SARS, SARS-Covid-2 can be spread via respiratory droplets and fecal oral routes. Once viral loaded droplets are airborne they can spread between 3 to 6 feet and the virus can survive on some surfaces for up to 24 hrs. This mode of transmission and spread not only led to a panic to buy disinfectants, sanitizers, and cleaners, but it necessitated the need to wear masks in all public areas. As previously mentioned, because SARS-Covid-2 has asymptomatic carriers, the virus can spread without the carrier knowing they are transmitting the virus. By social distancing, wearing masks, washing hands, and disinfecting surfaces the spread of the virus can be mitigated. Unfortunately, as of July 31, 2020 the virus has not been squelched and in states like California, Florida, and Texas the number of cases has increased for a variety of reasons, including the unwillingness of some to simply wear a mask.

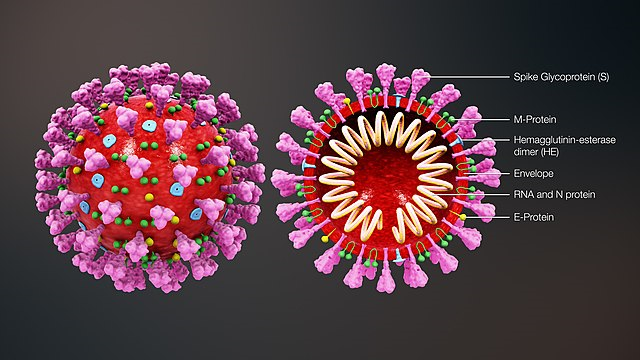

Like the common cold, and SARS, SARS-Covid-2 has a similar structure. Between SARS, SARS-Covid-2 there are different spike proteins, making each unique from one another. Referring to Figure 3 below, SARS-Covid-2 has S spike proteins that are responsible for binding to Type 2 pneumocytes and SARS-Covid-2 releases Positive Sense Single Stranded Ribonucleic Acid (SSRNA) into the host cell. What makes all viruses so difficult to contain is their ability to efficiently hijack the resources of the host cell to make very many viral particles. When the viral particles are assembled, then they can be spread to other uninfected host cells and the process continues. How does it do this? When the spike proteins attach to the Angiotensin Combining Enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptors on the surface of the host cell, Positive Sense Single Stranded Ribonucleic Acid uses the cells’ ribosomes and translation processes to produce more protein molecules (viral polyproteins). COVID -19’s SSRNA can also synthesize more SSRNA via RNA dependent RNA polymerase. With the combination of polyproteins from translation, proteinases and SSRNA more viruses can be made with the assembly of the viral components. If the host cell is destroyed, new viruses are ejected out of the cell and the virus spreads to infect more cells.29

Figure 3: SARS-Covid-2 structure.30

As many have come to understand, the respiratory system is the first system attacked when someone is infected with coronavirus. What actually happens to the respiratory system cannot be discussed without discussing human immune response. Initially, the alveoli are the targets for the virus. Deep in the respiratory tract the virus attaches to type 2 pneumocytes (structures that produce surfactants) and Type 1 pneumocytes (structure that aide in gas exchange). The increase in viral presence and the destruction of the host cell’s pneumocytes stimulate the release of inflammatory mediators from the immune system. Inflammatory mediators signal macrophages. When the macrophages are stimulated, they release cytokines that cause the Cytokine Storm. This is similar to an army sending out all the troops to battle, without knowing exactly what the enemy’s strengths are. Meanwhile, as the Cytokine Storm is rushing through the body, the endothelial cells react (smooth muscles dilate). This response leads to vasodilation of the capillaries and an increase in their permeability. With an increase in permeability of the capillaries, they push out their plasma fluid into interstitial space between the alveoli and the capillary. The fluid compresses the alveoli and forces the thin alveolar tissue to take-in interstitial fluid. As more fluid accumulates inside the alveoli, surface tension increases, and pressure against the walls of the alveoli increases. This buildup of pressure eventually can lead to alveolar collapse. The collapse of alveoli then reduces the overall volume of oxygen that the lungs can take in, and reduces the amount of carbon dioxide that can be removed. The total effect is hypoxemia, a decreased level of oxygen in the blood. 31

Because there is less alveolar function, a person with COVID-19 has to work harder to take in oxygen which might require a patient to require ventilation assistance. Inside the alveolar cells begin to accumulate and consolidate preventing gas exchange and hypoxia. Patients with these accumulated cells, struggle to take in air and start to cough releasing more viruses on respiratory droplets. Through this mode of transmission others can become infected and the cycle begins again.32 It is important to discuss with students that although the focus of this segment is SARS-Covid-2 effects on lung tissue, the ramifications of SARS-Covid-2 on other organ systems is enormous. In fact, we see many cases in which SARS-Covid-2 patients die from multi-organ failure beyond the expected respiratory failure. These cases and the data are at this point changing as more people become infected and test positive.

A final point regarding SARS-Covid-2 is that being an RNA virus, it has the ability to rapidly mutate unlike organisms with DNA genomes, such as all animals. RNA viruses have large population sizes and short generation times; coupled with typically high mutation rates, this permits such viruses to rapidly evolve and thus potentially change to become better adapted to infecting the host. This change might be making new proteins to attach to a different host cell receptor, or a new sequence of its genome to fool a host cell from attacking its viral particles. Research and technology do their best to keep up with the latest strains of influenza viruses and pathogenic bacteria, but have not been challenged to keep up with the unknown diversity of viruses and other parasites in animal reservoirs. Only when zoonosis occurs do humans attempt to solve the problem. Our actions are almost always reactive rather than preventive. Unfortunately, at that point, containing the new pathogen or new strain of a once eradicated pathogen is too late.

Implications for Policy Change

How can humans minimize the risk of a new pathogen from emerging and creating a worldwide pandemic? Patz et al recommend changes to health policies that include reviewing policies that examine land-use changes that might be detrimental to human health and sustainable populations. In policy making, land-use considerations should be linked to sustainable practices that diminish the risk to human health and preserve habitats. Making decisions and policies that are narrow in their scope will lead to more reactive actions rather than prevention of emerging diseases. If a possible reason why EIDs are more prevalent is linked to deforestation, changes to agricultural land-use, and habitat fragmentation, then health care policies must include those responsible for land-use change decisions.33 A second recommendation by Patz et al includes the review of land fragmentation and public health hazards. Examples of this include assessing logging practices, dam construction, irrigation practices and many more.

Agreements related to land-use changes and preservation of habitat are difficult to accomplish because to have a discussion on this matter many entities must come to a unified goal that balances economic growth and biodiversity preservation. Those working to preserve habitats must contend with people who are in charge of agriculture, mining, urbanization, and coastline watersheds. At the same time, conversations must be had with different environmental groups who have different agendas whether it be to save the forests, to save the coasts, to save our oceans, or to save our ozone. All these groups are necessary to the conversation, but increase the difficulty of coming to an agreement. Lastly, to add to the complexity, even if countries, environmental groups, and businesses come to an agreement about balancing economy with habitat preservation, one variable remains that is unpredictable – human behavior. Human behavior and action will ultimately dictate the rate at which a pathogen becomes a pandemic or simply a blurb in a small’s town newsletter.34

Because the prevention of the emergence of disease is so complex and multi layered, multidisciplinary and multi-nation discussions need to be involved to create policies that preserve biodiversity while allowing for economic growth, healthy ecosystems, prevention of food waste, and conservation of cultural and indigenous practices. This type of work by groups like EcoAlliance is not easy and is often very slow.35 Big business, big pharma, and big Agra cannot be the only groups that dictate and determine which crops are grown, which habitats are disturbed, and which species are worth saving. White et al, call for the need for more studies and models that can assess the data being gathered surrounding LUCs and the potential pathogens that might emerge from those changes. There simply is a need for more work in this area in order for reliable science-based predictions to be made. With the complexities of biomes, the variety of viral hosts, and the rate at which viruses and bacterial can change, a model to predict the next outbreak seems unattainable.

In a 2020 book from the National Academy of Sciences, committee writers call for a need for a change to current strategies in response to pandemics. If nations, private and public research labs, and university research groups were able to share clinical and epidemiological data more freely without the fear of legal repercussions, or regulatory laws being broken, then perhaps an emerging disease can be prevented because of the shared knowledge between these groups. As it stands, researchers often do not publicly share their findings because of their fear of breaking regulations or local and federal laws. There is a need to create frameworks by which leading scientists in the field of epidemiology could collaborate with one another, discuss, and share solutions that might potentially prevent the next major epidemic.36

Comments: