Content Objectives

Guiding Question

How can representation of African diaspora history and culture enslave people, empower people, or overcome the past?

Prereading: Gaining Thematic and Cultural Background through Images

Before my students begin reading Gem of the Ocean, I will use images and artwork to help my students gain or activate relevant historical knowledge, begin to grapple with important theme topics, and get in the practice of using close reading skills for all texts, whether visual or written. In the sections that follow, I list several key background topics to help enrich students’ understanding of Gem of the Ocean and explain how the suggested art can help students gain knowledge and understanding of those topics, as well as an understanding of the significance of how artists represent African diaspora. In addition to the information provided below, I will also provide students with a bit of helpful biographical information on each artist. I will dedicate three to four 42-minute class periods to the examination of these works of art and discussion of background information.

Slave Ship: Introducing the Middle Passage

Fig. 1 Turner, Joseph Mallord, Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On), 1840, oil on canvas. Boston, Museum of Fine Art.

The pivotal City of Bones scene I described in the introduction references the Middle Passage of the Atlantic slave trade. I will use J. M. Turner’s Slave Ship (1840) oil on canvas painting (Fig. 1) to begin our use of images to discuss some of this history and its representation. Turner’s Romantic seascape painting portrays a ship moving off into the distance in the direction of dark skies representing the title’s typhoon coming on. Other than that splotch of black on the left, though, the sky is vibrant—a blend of reds, oranges, yellows, and even bright blues with soft white clouds behind the ship. The ocean waves are rough but not too violent yet. The viewer cannot get too caught up in admiring the sublime beauty of the seascape before noticing the arms and legs of the enslaved Africans thrown off the ship. This horrific image was inspired by the 1781 scandal of Brittain’s slave ship the Zong, whose captain threw ill and near-death enslaved people overboard to claim insurance money3. Some viewers might believe Turner’s intention is to elicit shock, pity, or rage within his viewers while denouncing the evils of the slave trade. However, some details, such as Turner’s attention to the beauty of the natural setting and the fact that beyond this painting Turner did not leave much indication of his opinions on slavery4, add more complexity to this work.

Marcus Wood’s Blind Memory: Visual representations of slavery in England and America offers some interpretation and history that will help illuminate the class’s discussion on this painting. Wood argues that Turner’s painting “is the only indisputably great work of Western art ever made to commemorate the Atlantic slave trade”5. His lengthy interpretive history of the work presents an array of readings through history—ranging from comedic responses to the slave’s leg in the foreground6 to comparisons to the biblical story of Noah’s arc7 to connections of Turner’s color symbolism to violence and murder8. Wood concludes that Turner’s painting is “brave” in taking on such a difficult, horrific subject. His closing quotation of Ziva Amishai-Maisels presents the challenge an artist faces (particularly a white artist) when depicting the atrocities of the slave trade:

How does one combine the artist’s pleasure in the act of creation with the horrific subject matter which is the source of the creation? And finally how does one guard against the spectator’s being struck primarily by the beauty of the work, lest he/[she] feel that an atrocity can be beautiful?9

Furthermore, the class would benefit from bringing the question of race into the conversation: In what ways does the artist’s race impact their representation of the Atlantic slave trade and its victims? Should white artists avoid subject matter like this altogether?

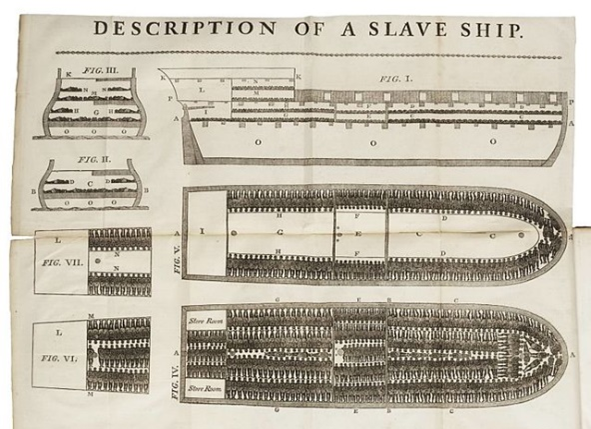

Significance of Representation: Comparing Images of Slave Ships

Fig. 2 London Committee of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, Description of a Slave Ship, 1789, woodcut illustration. Princeton, Princeton University Library.

The paintings I will feature for analysis in this grouping include the London’s Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade’s Description of a Slave Ship copper engraving (1789) (Fig. 2), Capture of a Slave Ship (1915 wood engraving based on Sir J. Noel Paton’s 1867 oil painting) (Fig. 3), Francis Meynell’s watercolor painting View of the Deck of the Slave Ship Albanoz (1846) (Fig. 4), and Kerry James Marshall’s Voyager (1992) (Fig. 5). See the Teaching Strategies and Classroom Activities sections for suggestions on how to use these images with students.

Although Description of a Slaveship is arguably the most powerful image of the British abolitionist movement, the image’s representation of the enslaved Africans is problematic. It’s ship deck lined with indistinguishable, dark human bodies presents the enslaved African people as a commodity. Granted, the creators intended this representation to horrify people and, thus, achieve their abolitionist agenda. However, the image presents another aspect of their agenda, “which dictated that slaves were to be visualised in a manner which emphasised their total passivity and prioritized their status as helpless victims”10. Francis Meynell painted his View of the Deck of the Slave Ship Albanoz in 1846 while working as a British naval officer stationed off the coast of West Africa. Having abolished its practice of the slave trade in 1807, Brittain now worked to end the slave trade in Spain, Portugal, and America; Meynell represents the deck of the Spanish Albonoz in his painting. Students might notice that Meynell’s depiction gives more humanity to its subjects than does Description of a Slave Ship. The chaotic and crowded arrangement of the enslaved, the subjects’ barely visible (sometimes absent) faces, and the use of light that highlights the structure of the ship more than the individuals’ features work together to create a sense of empathy and pity that only strengthens the narrative of the African enslaved as weak, hopeless objects11. J. Noel Paton’s Capture of a Slave Ship takes this representation further with its presence of British sailors reaching down into the ship’s hold to rescue the enslaved people. Students should notice the level of detail put into the features of both the enslaved Africans and the British rescuers, but they might question the accuracy of the image’s representation of the Africans—Do the features seem African? How much variety exists among the features when comparing one individual to the next? Furthermore, the enslaved in the ship’s cargo display expressions and gestures of fear, desperation, and near hopelessness, while their British rescuers, angel- or even godlike, reach down from above to save these seemingly “lost souls from the infernal regions”12.

African American artist Kerry James Marshall’s Voyager presents another perspective on the slave trade. The painting is based on accounts of the slave ship Wanderer that arrived with over four hundred enslaved West Africans on Jekyll Island, Georgia on October 28, 1858—an action prohibited by the 1808 “Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves”13. The Wanderer was a luxury yacht purchased by Savannah resident Charles L. Lamar and transformed into a slave ship. Unlike the crowded holds of the previous ships, Marshall depicts the Wanderer as a small sailboat transporting only two individuals: a female kneeling at the prow, looking forward into the distance and surrounded by a wreath of pink and white roses, and a male, whose upper body is obscured by the ship’s sail. This representation allows viewers to focus on the individuality of the people, rather than the horrific conditions they faced. The image offers plenty of detail to remind readers of the terror, violence, and bondage: the woman’s facial expression (Even though some students might observe a sense of strength.), the black sky, the windowless shotgun house, the diagrams of fetuses that seem to bleed onto the image below, the people’s nakedness, the skull in the bottom, center. However, curator Abigail Winograd observes other key details that represent the beauty, strength, and creativity of the cultures represented:

Lyrically drawn Afro-Cuban nsibidi, an ideographic form of script from Nigeria, and Haitian vévés (religious symbols) adorn the sail and sky. These drawings reference the religious practices and cultural forms brought by enslaved Africans to the New World, serving as evidence of the creative forms of active resistance and sophisticated assimilation that resulted from the forced African diaspora.14

Racism, Migration North, and Pittsburgh

The images in this section will help students gain knowledge and understanding of the physical and cultural setting of early-1900s Pittsburgh. Students will participate in a gallery walk activity to help them discuss the images, the significance of representation, and the attitudes they suggest (See Classroom Activities.)

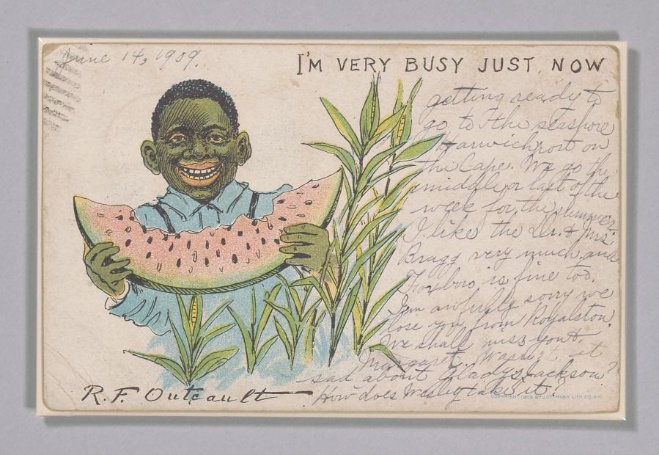

Fig. 8 Outcault, Richard Felton. “Postcard depicting a caricatured boy eating a slice of watermelon,” 1909, ink on paper. Washington, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Minstrel show propaganda and artifacts of every day racist paraphernalia are revolting and can illustrate the pervasive racism and stereotypes that impacted African Americans at the turn of the 19th century. Minstrel shows began in New York in the 1830s and were widely popular during the setting of Gem of the Ocean. Satirizing plantation life, actors in blackface portrayed African Americans as ignorant, crude, dishonest, and licentious. The shows used comedy to create and perpetuate stereotypes and unify white audiences by giving them a common object of ridicule. A poster for W. H. West’s Big Minstrel Jubilee (Figure 6) and an image of “The Original Jim Crow” (Figure 7) on a cover to an early edition of the Jump Jim Crow sheet music speak to the popularity of these shows in the northern states, as well as the damaging, unfair stereotypes they perpetuated. Images like the postcard featuring a caricature of an African American boy eating watermelon (Figure 8) accompanied by the text “I’m just very busy right now” show the just how pervasive these stereotypes were15.

Nineteenth century photographs of Pittsburgh will help students visualize the setting of Aunt Ester’s home on the Hill District in 1904 Pittsburgh, as well as the conditions of the factories and mills that affected several of the play’s characters. Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art has helpful photographs in its collection, including mill scenes (Figures 9 and 10), the Detroit Publishing Company’s “Panoramic View of Pittsburgh” (Figure 11), and “Pittsburgh: Market District” (Figure 12).

Through the 1960s, African American artist Romare Bearden, who became a sort of muse for Wilson, created collages that depicted African American life in the rural South and the urban North. While the collages are reminiscent of life in the earlier decades of the 20th century—the decades leading up to the Great Migration—they resonated with the African American fight for civil rights in the 1960s, illustrating that “the strong figures of the past are a part of the powerful figures of the present”16. When reading Bearden’s collages, it is important to keep in mind that his work was both respected and criticized. Some viewers saw his depictions of rural African American life as representing “the picture of contentment of the old South” and at least inadvertently supporting stereotypes of African Americans in a “primitive environment”17. In Tomorrow I May Be Far Away (1966/1967) (Fig. 13), Bearden shows three individuals in a rural setting—perhaps a home and small farm that the individuals own. Bearden’s collage style could suggest several possibilities: the disrepair of the home, the fragmented or uncertain lives of the people hoping for something better, or—as it does in many of his collages—the complex cultural background of his subjects. The woman looking out the window on the left has two mismatched eyes, one eye looking upward—maybe suggesting a sense of hope18. Her large masculine-looking hand resting on the window ledge indicates the arduous work she invests in maintaining the family’s land and home. The man resting outside the house in the center of the collage sitting with his hands folded and smoking a cigarette. Perhaps he is taking a rest from the day’s hard, manual labor, as suggested by his blue uniform-like clothing. Neither individual looks happy, but one could argue that they are proud people who work hard for what they own. As the title and the train (a common motif in Bearden’s rural collages) in the background suggest, this couple may be contemplating change, maybe change that will take them to new opportunities in the North 19. Bearden’s Pittsburgh (1967) (Fig. 14) includes images presented in the Carnegie Art Museum’s early 20th century photographs, such as the railroad tracks and the machinery of the mills and factories. The train is now in the foreground, indicating the arrival of African Americans from the South. The individual in the foreground is dressed for work in the factories. His head looks like that of a child, suggesting the start of a new life for those who migrated north.

Hybridity and Creolization in Gem of the Ocean

According to the authors of American Encounters: Art, History, and Cultural Identity, “[s]cholars of the African diaspora have attempted to account for the many complicated ways that African customs and beliefs survived in the New World. They use the term ‘creolization’ to describe the process of give-and-take that occurs when different cultures exchange practices and in the process produce a new and hybrid culture”20. Scholar Herman Bhabha labels this process as hybridity—the creation of new, transcultural forms created within the contact zone between two cultures. Hybridity shows up in linguistic, cultural, political, religious, and artistic forms21. Understanding Gem of the Ocean’s African American characters in the context of hybridity will help students better understand Wilson’s use of allusions and spiritual references. He references Christian imagery alongside African spiritual beliefs; ancestor reverence beside reverence of Jesus Christ; Christian values alongside ancient African rituals. Characters like Aunt Ester are not bothered by any seeming ideological conflicts because they are part of a new culture, a hybrid culture that blends elements of both African traditions and Christian beliefs. Teachers could engage students in discussing one or both of the following Bearden collages as another pre-reading activity. If students seem ready to begin reading the play, save the discussion of these images for several scenes into the play, such as after Act I, Scene 1 or 2.

Hybridity in Two Romare Bearden Collages

By analyzing Bearden’s The Prevalence of Ritual: Baptism (1964) (Fig. 15), students can quickly develop an understanding of the phenomenon of hybridity in America. This collage’s visual references to both Christianity and relics of African tribal rituals make a great preview of the hybrid culture of the characters in Gem of the Ocean. Furthermore, the work’s emphasis on the power of water to renew is also an important connection to Wilson’s play. In the foreground, three people stand in a body of water, experiencing the rite of baptism. A hand pours water on the head of the woman in the center, and the man on the right raises his hands as if in a posture of praise or surrender after emerging from the water. Bearden uses fragments of photographs of African Americans and images of African statues or sculptures to form the shape of each person. Through this technique, Bearden suggests that these people are neither solely African nor solely American; they are a new culture that is a hybrid of both. The distant church in the upper left suggests that while the rite of baptism links these individuals to the Christian faith, their cultural identity encapsules African traditions. The small boat in the lower left corner might remind viewers of the journey through the water that forever changed the history and identity of these individuals’ ancestors. Suggesting a continuation of change and movement, Bearden places a train towards the upper left in front of the church. Kymberly Pinder comments that Baptism is part of Bearden’s larger body of religious work that features water symbolism, rebirth, and ritual. Bearden ties baptism to a rite shared through history across many cultures22.

Bearden’s Sermons: The Walls of Jericho (1964) (Fig. 16) is another collage that illustrates hybridity. Like Baptism, this collage contains an array of references to African cultures and religions, Christianity, and other societies. Sermons is more complex and will require more class time to analyze. Students will need to have at least a basic familiarity with the biblical story of Jericho in the book of Joshua. See Nnamdi Elleh’s essay “Bearden’s Dialogue with Africa and the Avant- Garde” for a deeper analysis of this collage23.

Reading: Using Artwork to Enlighten Understanding of Gem of the Ocean

Pairing artwork with the text is a way to help students interact with the literature, understand allusions and imagery, become more fluent in discussing the culture and traditions of the play, and develop deeper understandings of the play’s themes. During the two-week period that students read the play, I will incorporate select works of art to help students achieve these goals.

Aunt Ester: Ancestor

Aunt Ester is the spiritual guide of the community. After their examination of hybridity in Romare Bearden’s works, students should feel more confident recognizing and understanding the various belief systems present in her stories and advice. She gleans wisdom from the stories of the Bible, yet she exudes a mystical knowledge that connects to African heritage. Many critics link Aunt Ester’s connection to the water and her status as a healer in the community to Oshun, the Yoruba goddess of the rivers. Furthermore, Aunt Ester’s mythology extends beyond the lifetime of a single person. She says she is 285 years old in Gem of the Ocean, which places her symbolic birth date in 1619—giving her the knowledge of African history since the day her people first arrived in North America. She appears throughout Wilson’s Century Cycle plays, wrapping the entire cycle and its characters in African mythology24.

After students have read Act I, Scene 2, use Bearden’s Prevalence of Ritual: Conjur Woman (1964) collages to spur on their analysis of Aunt Ester’s character. Bearden often remade versions of his collages and has two versions of this collage. He created the first version (Fig. 17) for the 1966 First World Festival of Negro Arts held in Dakar, Senegal, to achieve the festival’s goal of “exploring commonalities among the visual, literary, and performing arts of the African diaspora”25. In both versions, Bearden combines pieces of human images and images of African sculpture and relics to create the woman. The first version presents a full body view of the woman. She has two different hands: a realistic human-looking hand that rests in front of her body and an upraised, much larger hand reminiscent of a traditional African sculpture. On this upraised hand rests a bird, suggesting her connection to both nature and her African heritage. The woman’s clear eyes and upward gaze suggest her confidence in her environment and her connection with a higher being. Bearden’s second version of Conjur Woman features a closer mid-level portrait of a woman. Her upraised right hand composed of pieces of two different realistic-looking African American hands could suggest confidence and spiritual authority—a notion that is also indicated by the white garb clothing that arm. Her left hand, the hand of an African sculpture, rests in front of her and, again, holds a leaf that connects this subject to nature and African heritage26. Students also should notice the indoor setting of this second version and the full moon outside the woman’s open window that also connects her to nature. After students consider both versions of the collage, they will use their visual and literary analysis skills to argue which version they believe is the best representation of Aunt Ester (See Teaching Strategies.)

Black Mary: The Protégé (Representations of African American Women)

Black Mary is a younger African American woman under Aunt Ester’s mentorship. She will become the carrier of Aunt Ester’s name, role, and history. After reading Act I, Scene 4, use these images to help students analyze the relationship between Black Mary and Aunt Ester and Wilson’s representations of African American woman through these characters (See Teaching Strategies and Classroom Activities.)

Fig. 21 Moorhead, Scipio, “Portrait of Phyllis Wheatly,” 1773, engraving. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Bearden’s Prelude to Farewell (1981) collage (Fig. 19) is set in the South in the moments before saying goodbye to a loved one leaving for the North27. Bearden’s ever-present train chugs past the window, symbolizing this movement and change. However, students could make connections to the characters and imagery of Gem of the Ocean. The maternal figure in the foreground might remind students of Bearden’s Conjur Woman collages. She seems to be a mother or grandmother supervising the younger woman in her private act of cleansing. The woman’s headwrap, jewelry, and African sculpture-like facial features represent her as the holder of the family’s traditions and heritage. The beauty of the woman’s body and the presence of this older woman transform the younger woman’s bathing into an act of purification and ceremonial cleansing28. Students should consider the ways in which this collage relates to Black Mary and Aunt Ester.

Although again set in a rural setting, students could draw connections between Bearden’s Pepper Jelly Lady (1980) (Fig. 20) and Black Mary or Aunt Ester. The train in the background again suggests movement north to a better life and progress. The Pepper Jelly Lady, however, with her confident stance and straight gaze beyond the relics of rural life (such as the rooster), is confident in her identity and new opportunities that lie in the direction of her gaze beyond the frame of the collage. Her basket is full of pepper jelly, a Southern and Caribbean delicacy that shows that this woman is “a woman of skill and cultivation, a rooted cultural bearer”; she is “one of Bearden’s many powerful women, Northern and Southern, young and old”29. What comparisons and contrasts do students notice between this woman, Black Mary, and Aunt Ester?

Scipio Moorhead’s Portrait of Phyllis Wheatley (Fig. 21) is worth consideration because it is “perhaps the first portrait (1773) produced by an African American of a member of his own race”30. The portrait depicts Wheatley, a then renowned Bostonian poet (and slave), in a posture of contemplation as she writes poetry. The image makes interesting contrast with the character of Black Mary, as it represents an African American woman engaged in intellectual academic work, rather than the domestic work that so often trapped African American women and the art that represents them.

The two Jamaican women posing in Kehinde Wiley’s Portrait of John and George Soane (2013) (Fig. 22) exude power and confidence. Wiley’s version is modeled after William Owen’s 1805 portrait of John Soane’ sons: John Soane, Jr. (right) had just returned from a semester of study at Trinity College, Cambridge, and his younger brother George was soon to follow in his footsteps31. Like many of Wiley’s portraits, his replacement of the white, European subjects with African Americans wearing street clothes is a move that reclaims power in art’s representation (or lack thereof) of African Americans. His choice to feature two women in this portrait, speaks to his criticism of our history’s exclusion of African American women, especially, from the table of education and intellectualism32. Students should consider connections between this portrait and Wilson’s representation of Black Mary and Aunt Ester.

Reclaiming the Middle Passage: The Journey to the City of Bones

In Act II, Scene 2, during Citizen’s spiritual journey to the City of Bones, Solly and Eli wear European masks and play the role of slave trader chaining Citizen to the boat33. Students might find this moment strange or confusing. Before they begin reading Act II, use this section’s images from Isaac Mendes Belisario’s Sketches of Character to help them preview some of the history and symbolism of this moment. To hook students on this topic, consider showing a trailer or clip from the 2004 movie White Chicks, in which actors Marlon and Shawn Wayans are FBI agents who, for an undercover operation, must dress as young white women34.

Published in separate sections between 1837 and 1838, Belisario’s Sketches of Character consists of a series of lithographs depicting citizens and life in Kingston in the 1830s. Seven out of the twelve total lithographs are Belisario’s representations of the “Christmas Amusements,” celebrations, known as Jonkonnu, in which the formerly enslaved made revelry with music, dancing, and elaborate costumes that often satirized their white oppressors. Records indicate that these celebrations had been occurring on plantations since the 1700s or even farther back, but Belisario’s Sketches are the first visual representations of this holiday35. While the Europeans were fascinated with the festivities and saw them as an innocuous time of celebration that would promote cooperation and industriousness on the plantations throughout the rest of the year, these masquerades were forms of resistance that “subverted the colonists’ strategies for reinforcing social and gender hierarchies”36.

Fig. 25 Belisario, Isaac Mendes, “Koo Koo, or Actor Boy,” Sketches of Character, 1837[-1838], hand-colored lithograph. New Haven, Yale Center for British Art.

The “Queen” or “Maam” presided over the masquerades. In his “Queen or ‘Maam’ or the set girls” image (Fig. 23), Belisario presents her wearing an elaborate colonial dress and holding a slave owner’s whip. Other images feature actors who wore white masks and costumes that contained elements of colonial dress and traditional African attire. These images illustrate that the festival portrayed a “world turned upside down,” combining aspects of African religion and the European colonial practices that oppressed the enslaved37. The image titled “Jaw-Bone or House John Canoe” (Fig. 24) features the central figure of Jonkonnu, a masked man wearing a house on his head. The house-hat has its origins in African tradition, but over time the symbol became creolized and by the 1800s took on the form of a plantation, often referred to as a “baby house”38. The subversive symbolism of an enslaved man holding the weight of the entire plantation on his head is evident. While many—including the slave owners who watched these masquerades—read the white masks as satirizing white slave owners, Yale art history professor Tim Barringer points out that the white mask also has roots in a Congolese ritual honoring the dead39. The next two images titled “Koo Koo, or Actor Boy” (Figures 25 and 26) feature white-masked performers in exorbitant, colorful costumes referencing colonial and European Renaissance attire and a feathered headdress that seems inspired by African costume. Wearing a lady’s dress decorated with elaborate lace, the costume further subverts the colonizers delineated gender norms. These actors would have engaged in a competition in which they recited memorized lines from Shakespeare as they danced and performed40. While Wilson’s characters’ donning of European masks in Act II, Scene 2 is not a festive Jonkonnu celebration, discussion of these images before reading the scene will give students some language and understanding of history to work with as they analyze Wilson’s intent.

After students read Citizen’s journey to the City of Bones in Act II, Scene 2, engage students in an activity in which they return to the images representing the slave trade and middle passage from the Prereading: Gaining Thematic and Cultural Background through Images section of this unit (Figures 1-5). Ask students to select the image they believe best pairs with their reading of Citizen’s journey to the City of Bones and support their selection with interpretation of both Wilson’s text and their chosen image (See Classroom Activities.).

Comments: