Introduction

As a little girl growing up in the Little Village neighborhood on the southwest side of Chicago, I could see “beautiful clouds” coming out of a smokestack from my backyard. They were dreamy and beautiful, and I thought I was lucky to have a cloud factory so near me. This smokestack belonged to one of the two remaining coal plants within the city limits of Chicago, the Crawford Plant. This plant was located less than two miles from my home in one of Chicago’s 26 industrial corridors. My sister, along with my mother, were diagnosed with asthma in those early years. My mother later died at the age of 47 from colon cancer. While I do not know the root causes of her illness, I have always wondered if the asthma and cancer were due to environmental factors. After extensive genetic testing, my sisters and I know that her cancer was not hereditary, and thankfully will not be passed on to us through our genes. This further led me to believe that her illness came from her environment.

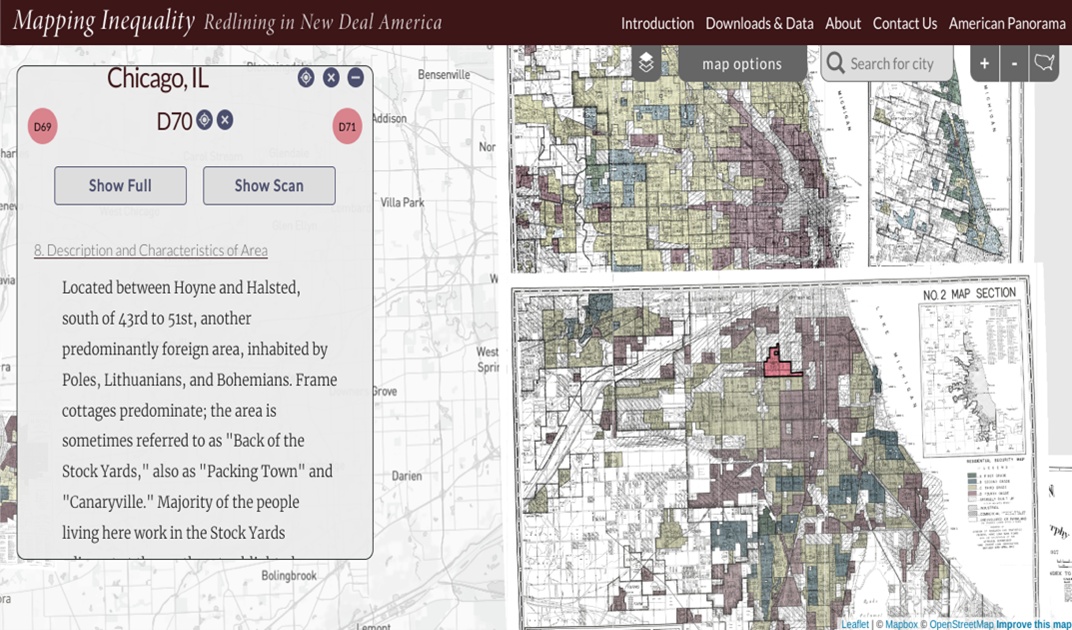

This unit centers around the southwest side of Chicago, its past, its present, and the relationship that past formal systems have had on present-day environmental factors. After the Great Depression and during the New Deal, the practice of redlining began with the implementation of the National Housing Act of 1934.1 This practice by government officials restricted investment in areas deemed high-risk by banks. High-risk often meant that Black people and immigrants were living in these areas, and therefore, they were not a good place for bank lenders to invest in. They were considered “undesirable”, and the practice was explicitly discriminatory. My neighborhood, Little Village was labeled as “definitely declining” by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC). This was the government agency that was formed by the National Housing Act to help stabilize real estate that had depreciated, and in the process gave neighborhoods these ratings.2

The term redlining refers to the red color used to denote the most undesirable areas.3 According to the Washington Post, decades of federal housing discrimination did not only depress home values, lower job opportunities, and spur poverty in communities deemed undesirable because of race, it is the reason that 45 million Americans are breathing dirtier air today.4 Due to discriminatory practices, communities of color in the Unites States are systematically exposed to higher levels of air pollution.5

In this unit, our students will perform an in-depth study of the air pollution of two neighborhoods that were given negative ratings by the HOLC. The first neighborhood, Back of the Yards was considered “hazardous” and is where I teach, and my students live (Figure 1). As stated earlier, Little Village was considered “definitely declining” and it is where I have lived most of my life. Both neighborhoods are located on Chicago’s southwest side and are predominately Latinx. According to an article recently published in the Washington Post, compared to White Americans, Black and Latinx Americans live with more smog and particulate matter from nearby industry in areas that were redlined.6 This is important because particulate matter air pollution is connected to lung function, asthma attacks, and cardiovascular diseases, therefore putting people of color at greater health risks, ultimately impacting their quality of life. One recent study concluded that there is a significant positive association between particulate matter 2.5 exposure and the risk of lung cancer incidence and mortality.7

Figure 1: Redlining Map of Chicago’s Back of the Yards Neighborhood.8

Comments: