Content Objectives

In this 6-week curriculum unit, newcomer MLL students will analyze the theme of images from the American Industrial Revolution and the Mexican Industrial Revolution. Students will learn how industrialization in these two countries has shaped the physical landscape, as well as the landscape of living conditions and outcomes for human populations. Students will apply an ecocritical lens to observe, question, and analyze the environmental degradation of a landscape and the impacts on local human populations; moreover, students will reflect upon the ways in which U.S. policy and transnational industry are driving environmental and social issues in the border cities of Mexico. This unit has three primary content objectives, with embedded language objectives intended to scaffold student progress toward mastery of the overarching content goals.

The first content objective will center on the process of visual analysis to carefully observe and describe an image. Students will learn, practice and apply visual analysis to make observations and draft questions to drive research about the history of an image. Through visual analysis, students will observe the features of an image, with a particular focus on the actions, objects, and beings within the image. Students will learn and apply the present and present progressive verb tenses to describe the images.

My second objective for this unit will focus on inquiry-driven historical research to determine the ecological and social impacts of industrialization on people. After visually analyzing an image, students will learn and apply WH-question forms to interrogate the image. This method will require and guide students to set a purpose for researching and gathering information about the artwork and time period. Students will then read short, level-appropriate text sets to answer WH-questions drafted during the initial visual analysis to determine the ecological, social, and historical context from which the image was created. With the information that students gather from these images, they will produce short writing compositions that demonstrate their understanding of the history surrounding each image.

My final content objective for this unit will target the skill of theme-identification of an image, supported by evidence and reasoning gathered from the image and inquiry-driven background research. Throughout the unit, students will work in whole-class, collaborative, and independent practice models to use and interpret evidence to identify themes of images. Upon the conclusion of this unit, students will have acquired the vocabulary, grammar functions, and paragraph-level rhetorical structures to adequately construct an evidence-based analysis of the theme of an image.

Ecocriticism

Ecocriticism is a field of art history that analyzes the role and relationship of the natural world in works of art. According to Karl Kusserow, ecocriticism is defined as “an analysis of cultural artifacts, literary and material, that, against the usual anthropocentric mode of the humanities, attends to environmental conditions and history and to considerations of ecology…” and how humans have interacted and been shaped by these factors over time.5

Though the field of ecocriticism has grown in prominence in recent decades, there are centuries worth of landscape art that has provided rich commentary on the interaction between the land and the people. Landscape art is not only valuable as a visual reference for environmental issues faced by different generations of human populations, but comparative studies of these works of art across time provide evidence of broad cultural shifts in human attitudes toward nature and human interactions with the natural world. Analysis of these works of art also reveal the pervasiveness of colonial powers and their spread of influence and extraction across the globe.

As the environmental hazards and effects of climate change caused by rapid and widespread industrialization are being fully realized, ecocriticism grows an ever more relevant way for analyzing art and understanding historical events and social movements. Thus, my students will use an ecocritical lens to analyze each image.

The American Industrial Revolution

Following on the heels of the British industrial revolution, America’s industrial revolution began in the late 18th century and accelerated in the 19th century with technological innovations that would radically reshape the American ecological and social landscape.

The rise of mills and factories to mass-produce goods like textiles, shoes, paper, and iron wares altered the American natural landscape. Though small, water-powered mills had existed for some time, new, industrialized mills required greater energy. Water-powered industries built high dams to harness the required force to run the factory; however, these dams prevented fish from spawning and often led to flooding. Moreover, fresh streams and ponds frequently became dumping grounds for industrial waste. These fresh-water resources were further contaminated by unprecedented levels of raw sewage from the sudden population boom of factory workers that moved into urban areas in proximity to the factories.6

As industrialization grew, Americans shifted from rural to urban living and many Americans moved to growing cities to seek employment. This sudden wave of rural migration and international immigration led to overcrowded and unsanitary conditions in cities. In addition to water pollution from industrial and raw sewage dumping, new urban residents were exposed to uninhibited air pollution and particulate matter from coal-burning factories.7

“Dust Storm, Fifth Avenue”8

This is evident in John Sloan’s 1906 painting “Dust Storm, Fifth Avenue,” in which New York City residents run for shelter during a dust storm. A massive brown cloud of dust barrels down the street toward fleeing New Yorkers in a wind tunnel created by the newly constructed Flatiron Building, which was the tallest skyscraper in an otherwise low-rise section of New York City in 1902.9 The tall, sleek building that divides two busy streets of New York City undoubtedly represents the rapid progress of a fast-paced city. However, the imposing black and gray storm cloud that eclipses a light blue sky appears to emerge from the building’s roof and conveys a clear threat of danger that is bearing down on the urban landscape. In order to construct skyscrapers like the Flatiron Building that now define the New York City landscape, the previous ecosystem of trees and grass was destroyed, leaving flat ground for new construction and compacted dirt streets. As a result of “the subtraction of the organic infrastructure from the landscape,”10 city dwellers faced environmental hazards from the ground that compounded the air pollution, notably “foul air that arose from soil contaminated by improper drainage, which not only infected the ground, but also polluted the atmosphere.”11

As a resident of New York City who was known for painting what was considered mundane and ordinary city life, John Sloan would have had an acute sense of the physical and psychological effects that industrialization had on urban residents. This is evident in the terror with which the people on the street flee from the dust storm. Panic is clear in the motion of the bodies that lean toward escape, and in the wide eyes on the face of a father holding the hand of his daughter, who has tripped and fallen in the street during their run to safety. The brown, black, and gray colors of Sloan’s painting not only depict the unrelenting air pollution that would have stained city buildings, but suggest a suffocating quality to the air that would have undoubtedly caused respiratory problems for many urban residents.

“The Lackawanna Valley”12

The ugly realities of the new urban landscape sparked a literary romanticism, “musing on metaphysical aspects of the natural world with criticism of noisy, filthy cities and regimented labor in prison-like mills.”13 Concurrently, the increasingly popular art of the 19th century idealized both picturesque and sublime landscapes of unspoiled nature. Artists such as Thomas Cole, Asher Brown Durand, and Frederic Edwin Church are well-known for their exquisitely detailed landscapes, emphasizing the grandness of mountains, rushing rivers, and the expanse of lush, old forests.14 However, as painters and artists fed the newly urban population’s imagination and nostalgia for the pristine nature that once was, deforestation and coal mining that sustained industrializing cities forever altered the romanticized, rural American landscape.

Like the American consciousness that celebrated progress of industry while yearning for the beauty of untouched nature, a paradox of feeling toward industrialization emerges in the images produced in the mid-19th century. It is also worth noting that the theme and production of skilled artwork was often influenced by the desires of those who commissioned the art, which was limited to the very wealthy, many of whom were newly rich industrialists.

Fig. 1 George Inness’ 1856 “The Lackawanna Valley”

George Inness’ 1856 “The Lackawanna Valley,” for example, was commissioned in 1851 by The Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad to celebrate the railroad company's official incorporation.15 The picturesque landscape shows a rural laborer resting in the foreground, watching a train leave the center of a busy small town to continue its journey through the countryside. At first glance, the image is peaceful and quaint, full of natural greens and distant rolling hills that nestle the small town. However, upon further examination, the foreground is apparently littered with tree stumps. These tree stumps surround the resting laborer and the absence of the trees which once stood provide an unobstructed view of the train. Moreover, the pillowy white clouds of steam billowing from the train in the middle ground draw attention to the trails of white smoke from four industries in the town, which are also spread across the middle ground of the painting. Though Inness draws on the picturesque colors and techniques to depict the landscape, the clear imagery of deforestation and air pollution as a result of coal-burning industrial activity provides a prime example of the complicated attitudes regarding the ecological changes reshaping American landscapes.

“Addie Card, 12 years”16

Industrialization also redefined the nature of labor and American social-economic status. While industrialization created and sustained a large labor force that bolstered a robust national economy and growing middle class, it also accelerated wealth inequality between the rich and the poor. With little to no government oversight, industries could pay low wages and require employees to work long hours in dangerous, unhealthy conditions. Furthermore, female employees were often paid half of what their male counterparts earned17, and the exploitation of child labor was a common practice.18

The newly emerging field of documentary photography played an integral role in awakening the public consciousness to the practices of industry that took advantage of the most vulnerable populations. For instance, Lewis Hines’ 1910 gelatin silver print of Addie Card captured, in stunning sharpness, the reality of child labor in industries like textile mills. 12-year-old Card stares hauntingly and unsmiling into the camera with one arm gently propped against a spinning machine in the cotton mill. The contrast of the white spinners to the dark insides of the machine and the interior of the factory seem to envelop Card, suggesting the hopeless nature of a long life as an uneducated laborer with few options for social and economic mobility. The tattered and stained condition of her apron leads the eye toward her feet, which are filthy and bare. In 1910, Card would have been one of tens of thousands of children aged 10-15, nearly 18% of American children, who were industrial workers.19 Mill owners and wealthy industrialists claimed that child labor provided a welcome societal benefit by preventing idleness and providing economic mobility to poor families; however, this reasoning was a thinly veiled attempt to increase industrial output and further enrich the already wealthy industrialist.20

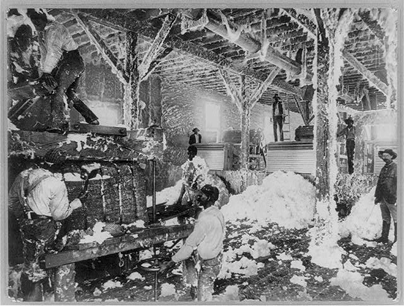

“Mississippi Cotton Gin at Dahomey”21

In addition to the exploitation of child labor, the American Industrial Revolution was fueled by enslaved labor and would continue to exploit the labor of free Black Americans. In the pre-Civil War industrial era, the U.S. became one of the world’s largest cotton suppliers.22 This intensified the monocropping of cotton in southern states and intensified the demand for slave labor. In the post-Civil War era, Black Americans faced racial and wage discrimination in industrial jobs and were often relegated to “the most difficult, dangerous, dirty, and low-paying categories of industrial work.”23 Additionally, cotton manufacturing remained a powerful industry in the years after the Civil War, though it could no longer extract enslaved labor from the American South. In years following the Emancipation Proclamation, the social and political efforts of the post-Antebellum South to relegate Black Americans to marginalized positions as low-paid agricultural laborers, or sharecroppers, sustained the profit-making machine of cotton manufacturers and textile mills. Moreover, artwork, media and displays of industrial progress solidified the way in which white Americans viewed the role and position of freed Black Southerners as second-class citizen laborers in the social-political order. For example, at the 1881 Atlanta International Cotton Exposition, attendees were invited to watch the entire production of cotton processing, which began with viewers watching laborers harvest cotton from the field to the viewing of a completed cotton garment. White workers, most of whom were women, operated machinery, while Black southerners harvested cotton in the fields. Anna Kesson writes that during the exposition these workers were “positioned as a kind of raw material themselves…” and “...were viewed as a work in progress, even while their labor remained crucial to national development.”24

Fig. 2 Detroit Photographic Company’s 1899 Mississippi Cotton Gin at Dahomey

Demand for cotton to supply textile mills remained insatiable at the turn of the 19th century. The chromolithograph photo Mississippi Cotton Gin at Dahomey illustrates the interior landscape of a cotton processing warehouse on the world’s largest cotton plantation in dark blacks, bright whites, and metallic browns, suggesting the physical and psychological darkness of this place.Though slavery had been abolished for over 30 years in 1899, Black workers are spread amongst the unruly tufts of sticky cotton that litter the floor and cling to both the workers’ clothing and the wooden structural beams of the cotton processing warehouse. To the right, a white overseer surveys the production process. A Black worker in the foreground looks intently at the cotton gin he is operating and a coworker watches the cotton gin operator, ostensibly to offer assistance or complete the next sequential task. The positioning of the overseer and the Black workers suggest an unease in the work environment that is reminiscent of a plantation social-political order in which little has changed since the era of enslavement. Notably, the white overseer wears clothing unblemished by the cotton that engulfs nearly every other part of the landscape, including the Black workers.

In addition to the positioning of bodies and coloring of the image, the very name of the cotton plantation in the image’s title and its history brings industry’s connection to slavery and the long-lasting social, political, and economic effects on Black Americans to the fore of the viewer’s mind. Furthermore, the historical acquisition of the land on which the cotton processing warehouse is located intersects with the systematic removal of Native Americans from their ancestral lands. According to the National Gallery of Art, “Dahomey Plantation was founded in 1833 by F. G. Ellis, who named the plantation after the Kingdom of Dahomey, the homeland of his enslaved workers in present-day Benin. Ellis was probably able to claim the land at this time because thousands of Native Americans had been forcibly removed under policies and orders enacted by President Andrew Jackson.”25

By observing, questioning, and contextualizing the history of each photograph and its connection to the American Industrial Revolution, students will learn about the dramatic ecological and social shifts in the American landscape. These images will provide students with dynamic examples with which to make concise observations with newly learned grammar functions and also serve as visual representations to support their understanding of complex processes in which history, ecology, and social issues intersect.

Student understanding of intersecting histories and impacts of industrialization is especially important when they transition to their visual analysis of art and images of the Mexican Industrial Revolution as this more recent example of industrialization is closely connected to modern transnational industrial practices that are actively impacting ecological landscapes and human populations.

The Mexican Industrial Revolution

Though large-scale industrialization in Mexico would not flourish until the later decades of the 20th century, Mexican artwork depicting industry and its influence on urban populations began in the early 20th century and would inspire a Mexican muralist tradition that remains an integral part of modern Mexican expression and activism.

Moreover, the cross-border movement of Mexican artists to paint murals of industry in the U.S. and Mexico reflects and foreshadows the forging of a U.S.-Mexico alliance that would accelerate destructive transnational industrial practices in Mexico in coming decades. Further, the economically extractive and ecologically damaging U.S. foreign policy mirrors a larger global pattern in the global North and global South in that “southern states are saddled with environmental burdens because they are marginalized within the global political economic order and represent a path of little resistance.”26

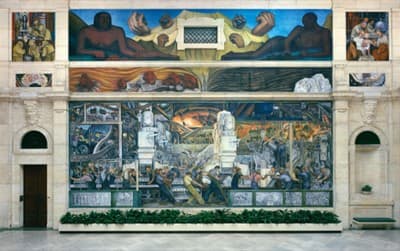

“Detroit Industry Murals”27

Diego Rivera is a Mexican artist who was a celebrated figure in the Mexican Muralist Movement of the early 20th century. As a prominent member of the Communist party in post-revolutionary Mexico, Rivera’s muralist work often idealized the laborer and depicted anti-capitalist scenes.28 In 1931, Rivera was commissioned by the Detroit Institute of Arts' Garden Court to paint a mural celebrating Detroit’s industry, a project that would take two years to complete. The massive, colorful, and stunning mural spans four walls and consists of 27 different panels that draw connections between evocative themes-- among them, labor, industry, ecology, and humanity. The largest mural is located on the north wall and famously portrays Detroit’s auto industry, specifically the manufacture of the engine and transmission of a 1932 Ford V-8.29

Fig. 3 Diego Rivera’s 1902 Detroit Industry Murals, North Wall[30]

Upon first glance, the viewer’s eye is drawn immediately to the largest central panel that nearly covers the wall and extends toward the ground. The scene depicts the inside of a factory, illuminated by the orange flames inside the mouth of a furnace belching smoke in the background. In the darker foreground, laborers strain in a synchronized motion to complete their repetitive tasks, eliciting the intense physical and physiological consequences of daily factory work. Laborers do not appear as distinct figures operating machinery; rather, the massive, interconnected machinery in each aspect of the foreground, middle ground, and background meld together with their human counterparts. In this way, the laborers are very clearly depicted as machine parts of the factory mechanism, rather than individuals.

In a long, rectangular panel above the laborers, Rivera depicts the geographical strata of the earth and its minerals. An explosion that appears to emerge from the top of the furnace in the panel below moves upward in the center of this panel; the minerals and stratified layers of earth move and ripple as a result of the explosion. This panel is suggestive of the mining industry, its impact on the earth, and the way in which these minerals drive industrial activities. Further, the physical space that the minerals occupy above the laborers suggests that the laborers’ work is foundational to industry, but also subterranean and therefore a resource to be extracted, much like the minerals depicted directly above their heads.

The central top panel of the mural depicts reclining deities on either side of a mountain covered in emerging fists of many different ethnicities. The deity to the left is an Indigenous person, while the deity to the right is an African American person. Each deified person is holding a mineral in one hand, iron ore in the hand of the Indigenous person and coal in the hand of the African American person. The location of this panel at the top of the mural and the nature in which these beings are depicted as god-like is a mythical reimaging of extraction and labor in American history in which people of color have full and equal access to the power and production of industry. However, this imagery is perhaps intentionally ironic, as the systemic dispossession of Indigenous people from their lands and land-resources, as well as the transnational removal and forced extraction of enslaved labor from African Americans is well-documented in American history.

The smaller top left panel illustrates a scene of workers in head-to-toe green protective gear and gas masks. The masks that the workers wear in the image are similar to those that American soldiers would have worn in trenches during a chemical attack. In the background of the panel, what appears to be a fully assembled bomb looms over the workers and is being prepared for shipment. The message of this panel is clear and critical-- manufacturing can be leveraged to wreak absolute destruction. On the other hand, the top right panel, located in direct opposition, shows a scene of the clergy vaccinating a child who is surrounded by idyllic animals. The physical and ideological opposition of the panel to its counterpart on the top left panel are made intentionally obvious to the viewer-- in the same way industry has the power to create destruction, industry also has the power to produce widespread good for humanity.

Though Rivera’s work suggests complex, and sometimes conflicting, ideas on the role of industry and its impact on the land and the people, it nonetheless brings forward the dynamics of power, race, ecology, and industrial technology-- subjects that were increasingly intersecting in transnational and global relations. Toward the end of the 20th century, industrialized U.S. cities like Detroit would see a decline in manufacturing and industrial production as the U.S.-based transnational companies began outsourcing labor and manufacturing to the global South, in places like Mexico, Rivera’s country of origin.

The Rise of Maquiladoras

Decades after Rivera painted the Detroit industry mural, large-scale industrialization in Mexico began with the rise of industrial factories called maquiladoras in cities along the U.S.-Mexico border. During WWII, the U.S. government permitted migrant workers, or braceros, to work in factories and agricultural jobs while U.S. workers served as soldiers overseas. When WWII ended, many migrants returned to Mexico; in order to prevent widespread unemployment, the Mexican government began to industrialize in northern border cities. Rapid industrialization was further galvanized by the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) that lowered tariffs and trade barriers for numerous U.S.-based companies to access cheap labor, lower production costs, and convenient geographic proximity to U.S. markets. This rapid rate of industrialization is evident in the number of factories in Mexico over the last 50 years. In 1970, Mexico had 72 factories compared to 620 in 1979. Today, there are nearly 3,500 factories along the northern U.S.-Mexico border.31

Transnational corporations, many of which are U.S.-based, built maquiladoras to financially benefit from significantly lower production costs. Because the government has fewer resources to enact or enforce environmental and social policies that protect landscapes and human populations from environmental hazards, transnational corporations are able to limit, or eliminate, costly measures that protect workers and the local environment. With little to no environmental regulations and a sudden rise of the maquiladora industrial activity, many border cities became increasingly burdened by environmental hazards such as “drought, groundwater depletion, water pollution, air pollution, and inadequate toxic waste management.”32

Located in the Chihuahuan desert on the borders of Texas and New Mexico, rapidly industrializing Ciudad Juarez experienced a sudden population growth due to an influx of migrant workers seeking employment in maquiladoras. Workers too poor to live in the city center, where wealthier citizens reside due to proximity to infrastructure, often build “self-help” dwellings that often have little or no access to city infrastructure like electricity, piped water, or sewage treatment. While the poorest residents of an industrialized city like Juarez are farther from the maquiladoras and thus less exposed to hazards like air pollution, they endure a greater exposure to natural hazards such as floods.33

Julian Cardona’s Documentary Photojournalism34

In Exodus/Exodo, by Charles Bowden, Julian Cardona’s black and white photography captures the land, the people, and the local and transnational forces accelerating undocumented immigration from Mexico and Latin America to the United States. Cardona, a lifelong resident of Juarez (or Juarense), documented decades of Juarez history, including its surrounding periphery in the Chihuahuan desert. His photos from the industrializing years that capture the outskirts of the city illustrate the self-made dwellings that began dotting the landscape as poor migrants moved to Juarez for manufacturing jobs.

One photograph in particular shows the landscape on the periphery of Juarez where the very poor reside. The glossy, black and white photograph spans two horizontally-oriented pages across the spine of the book and has no title. On the right side of the image, lining the foreground and continuing into the background are “self-help” dwellings that are constructed out of cheap, cast-off materials, like tires and wood pallets. Snaking along the sloping hill to the “shacks” are “outlaw electric lines” that illegally divert electricity from the grid to power the dwellings.35 In the background, sparse and scrubby plants dot a desert hill rising from the road. On the left side of the image, a woman walks down a hard packed dirt road toward her home. According to the caption, she is a Juarez woman on her way home from a maquiladora.36 Because of the location of most factories in the city center, it is likely that this woman traveled for some time to and from her job. Her geographical proximity outside of the city also suggests that she may have little, if any, formal access to infrastructure in her home, such as running water.

Few empirical studies exist to illustrate the depth of ecological impacts of industrialization on Mexico’s northern border due to limited government resources, including a lack of oversight and transparency, and an unwillingness to discourage transnational corporate investment. However, studies show that industrialized border cities face current and future water shortages due to rapid population growth from migrant workers. A great deal of hazardous waste byproducts that result from manufacturing processes have gone largely unaccounted for, despite strict transnational laws that dictate hazardous waste produced from industrial activities must be repatriated by the country of origin from which the manufacturing materials originate.37 Furthermore, solvents and heavy metals that are used in electronics production are believed to contribute to surface and water pollution in Mexico, especially considering that many border specialists suspect this type of hazardous waste is being dumped, untreated, into local sewer systems, waterways, or sparsely populated areas outside of city limits.38

“Under the Bridge/Bajo el Puente”39

Residents of border cities are mutually vulnerable to environmental hazards produced on both sides of the border and a dependence on a shared water source, the Rio Grande, or Rio Bravo as it is known in Mexico. In 2021, the city of El Paso released millions of gallons of wastewater over several months in the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo.40 Though this phenomenon may not be a direct result of industrial activity, it points to the shared ecosystem of border cities and the ways in which environmental degradation is impactful to residents of both cities. Furthermore, experts expect that water from the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo, which supplies both drinking water and water for agriculture, will be less abundant in coming years. A two-decade “megadrought” and higher temperatures from climate change have contributed to the shrinking of this critical river system.41 However, importantly, the city of El Paso benefits from the protective factors of well-developed infrastructure and the political force of the United States in the case of environmental disaster and water scarcity. In stark contrast, residents of the neighboring Juarez, do not benefit from the same protective factors.

Jorge Perez Mendoza and the border artist collective called Rezizte completed a mural along the Mexican side of the canal that channels the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo. The mural, which can be seen from the bridge connecting El Paso and Ciudad Juarez, draws on the Mexican muralist tradition of the early 20th century as a means of cultural and political expression. When interviewed about the mural’s significance, Mendoza described the way in which the mural highlights the unity, culture, and common history between the binational border communities. Additionally, Mendoza noted that the mural serves as a “pacifist call to aerosols instead of arms in protest of the contamination of the river that the U.S. and Mexico share.”42

The graffiti-style, spray painted mural, the largest artwork on the south wall of the canal, depicts long arms that stretch across both sides of the mural until the hands clasp in the center, forming a bridge that mirrors the physical border bridge above the mural. In the upper, left corner of the mural, a female maquiladora worker is surrounded by gray metal machine cogs as she busily completes a task. In the right, lower corner of the mural, a bracero farmworker tends to long, brown rows of a field as a yellow sun peeks over the horizon.

The mural is a proud celebration of the Mexican laborer, Mexican culture, and Mexico’s contributions to both Mexican and American industry. Perhaps more importantly, it occupies a commanding physical space that serves as a pop-art style announcement to border residents that the people of Juarez are similarly affected by economic and ecological issues fueled by industrialization that simultaneously affect neighboring El Paso. The bold and bright mural also serves as a public-consciousness raising visual of Juareneses’ labor contributions that have sustained and enriched the U.S. economy. In this work of art, present-day Juaraneses make clear that they reject marginalization and demand economic and environmental justice.

A Changing Social Landscape

In addition to the increased exposure of environmental hazards, residents of rapidly industrialized cities experienced a major social and cultural shift as women began working in the maquiladoras. In traditional, pre-industrialized Mexican culture, women were expected to care for families at home. Women who worked out of the home were often considered “public women,” a term that could connote loose moral values. According to Melissa Wright, “the public association of obrera (worker) with ramera (whore) was something that factory workers faced constantly, as women who walked the streets on their way to work…” In other words, women working in maquiladoras were frequently associated with women who walked the streets working as prostitutes at night.43 This association was especially relevant in Ciudad Juarez, where prostitution was and remains legal and is not restricted to a particular zone in the city.44

Juarez came under international scrutiny in the 1990s and early 2000s as the number of missing and murdered women steadily climbed and local activists, many of whom were mothers to murder victims, called attention to the growing number of femicides. Femicide is defined as a homicide of a female victim because she is female. In the case of the Juarez femicides, the Spanish term feminicidio is also often used to describe the killings as it emphasizes the female condition and the impunity with which many of these femicides are committed.45

According to a 2005 article published by Amnesty International, 370 women and girls were found murdered in the city of Juarez and surrounding areas in Chihuahua, though this statistic does not account for the many girls and women who remain missing persons.46 These murders made headlines between the 1990s and early 2000s when bodies of female victims were discovered at dump sites outside of the city. For example, in 2001, eight female victims were discovered in an abandoned cotton field called el Campo Algodonero near a maquiladora headquarters.47 Of the female victims discovered during these decades, many were young maquiladora workers..48 To date, the majority of these femicides remain unsolved and little state action has been taken to resolve them.49

“Ni Una Más”50

In the 1990s and early 2000s, pink and black crosses became one of the most prolific visual symbols of activism protesting feminicidio. Pink crosses and black crosses against pink backgrounds were painted on telephone poles throughout the city and were often erected at dumpsites of female victims to keep the problem of feminicidio at the fore of the public consciousness. However, over time, rhetoric of governing officials and industry leaders successfully shifted public sentiment toward apathy; such rhetoric consistently mischaracterized victims as prostitutes, female activists as hysterical, and activist groups as self-interested in profiting off the grief of victims’ families. Moreover, a dramatic increase in cartel violence and the subsequent militarized state response further withdrew public scrutiny of government indifference in pursuing justice for families of femicide victims.51 Nonetheless, activists and family members of murder victims continue to demand justice, and pink crosses, like the one on the Paso del Norte International Bridge have become a part of the Juarez landscape.

Erika Schultz’s photograph of a black cross against a pink background at the Paso del Norte International Bridge is featured in a documentary project by the Seattle Times that integrates video, poetry, art and photography to narrate the story of the Juarez femicides.

In the very center of the colored photograph, a great black cross hangs on a bright pink background that is covered in large black nails. Nailed to the front of the large black cross is a pink sign that reads “!Ni Una Mas!,” or “Not One More!” The powerful symbol is difficult to ignore with its clear exclamation demanding an end to feminicidio. However, the photograph is almost purposefully mundane. It captures the everyday life that continues around a symbol of protest against extreme violence. Thus, the ordinariness of the photo and its content suggests a dilution of the cross’ symbolic power-- it has become a regular fixture that simply blends into its otherwise ordinary landscape

To the right of the cross, two workers talk, one leaning against a yellow handcart, and another standing upright in an orange reflective vest. To the left of the cross, cars wait in line to cross over the border bridge under a partially-obscured road sign that reads feliz, or happy. Crutches lean against the pink, wooden background to the left of the cross and a small table with stacks of newspapers, topped by a rack of magazines, sits in front of the cross, obscuring a word written in black paint. The photograph marks both the tireless efforts of anti-feminicidio activists, as well as the public apathy now characterizing the political landscape on both sides of the border. The once provocative and disruptive symbol of feminicidio that has been marginalized in the physical landscape represents the prioritization of economic gain at the expense of female lives.

After learning and practicing the observation, analysis, and research skills with the image set from the American Industrial Revolution, students will apply their newly learned skill set to analyze an image set from the Mexican Industrial Revolution. In this part of the unit, students will determine the ecological and social impacts of industrialization on Mexico. Students will be able to compare and contrast how industrialization changed the Mexican landscape with the ways in which the American landscape was shaped by industrialization. Further, students will reflect upon the intersection between American industrialization, and the practices of labor and resource extraction that have shaped social and ecological disruption in the Mexican landscape.

Comments: