Content and Learning Objectives: A Brief History of ‘Modern’ Pittsburgh

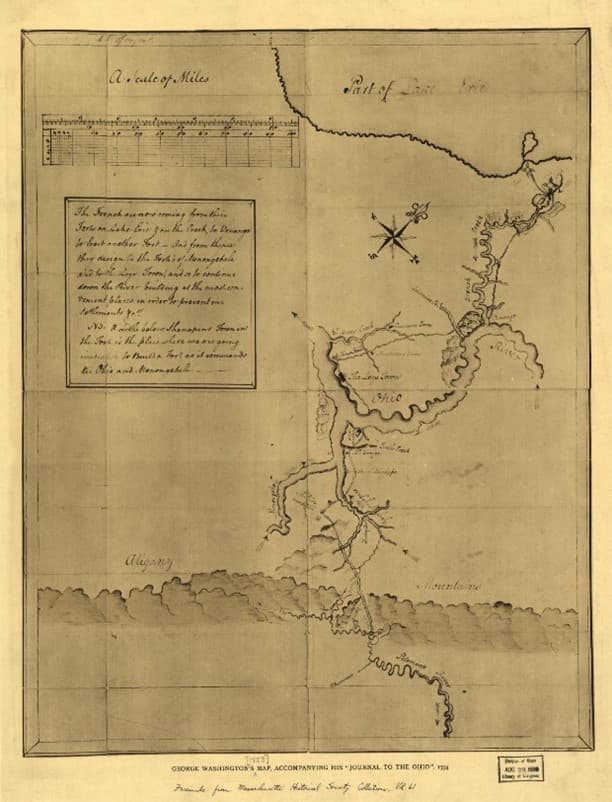

George Washington’s Hand-Drawn Map of the Forks of the Ohio5

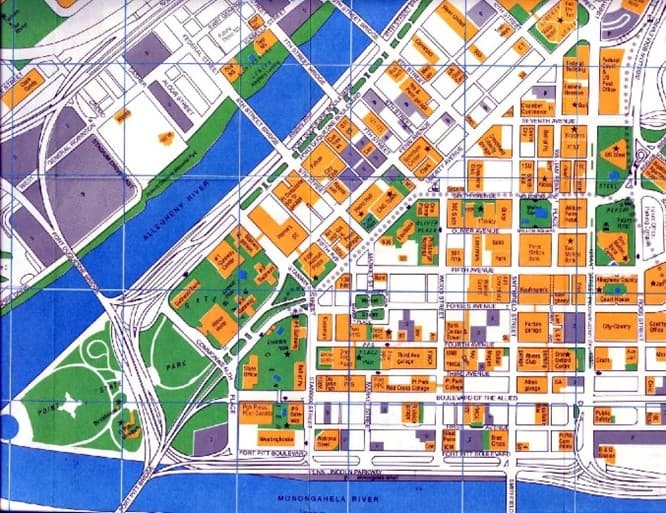

Pittsburgh Footprint Map 1995-20176

The main objective of this unit is to take a critical look at Pittsburgh’s history from George Washington’s search for a suitable and strategic site for his fort on the Western frontier, through the industrial revolution and its impact on the area, leading us into the present. Where, we will discuss, does this history lead us in the future.7

As with any landscape, the land itself was what everything starts with. Before the city and even before people, what would become Pittsburgh was a series of stone terraces formed from the sediment of fossilized plants that grew and then decayed, at various rates and at various times with the shifting of the Atlantic Ocean. The area was periodically dry but also periodically flooded. There were vast swamps that extended into the Midwest. Nestled between these layers of limestone, sandstone, and shale nature’s processes in our area had created natural gas, large quantities of oil, and coal in an abundance that was not to be found anywhere else on our planet. While this was going on, rivers were carving out the valleys and creating the narrow but habitable flatlands and plateaus along these new water ways.8

This all took millions of years and we cannot forget that there were inhabitants in the area and that civilization did not start with the arrival of the Europeans. However, our conversation will begin with Pittsburgh’s history from that recorded Western point of view, which starts in 1753, with the aforementioned quest h George Washington’s to find a suitable and strategic site for a military fort.9 As a nation ever expanding westward, what was to become Pittsburgh, with its rivers flanked with flat lands protected by the surrounding hills lent itself perfectly for a young Washington looking for the perfect strategic military placement for a new British fort.10

In the images above, you can see a map that was hand drawn by George Washington during his search for that suitable military complex. Here, you are already able to see the beginnings of the area, complete with many of the names that are still used today. Compare this to the modern footprint map of the same area. You can see how densely developed the area is now.11 Comparing and contrasting these images will be part of our initial discussions on the development and evolution of our area.

By the late 1700s and the United States had formed as a nation and the frontier town of Pittsburgh, perfectly located at the confluence of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and the Ohio Rivers, was to become a ‘lynchpin’ for the growing commerce and migration from eastern cities of Baltimore and Philadelphia to the new settlements forming in Ohio. A turning point was reached with the advent of the transcontinental railroad in the middle of the nineteenth century. At that point it became easy for both freight and passengers to bypass Pittsburgh and its mountainous area to reach the new cities of Louisville, Cincinnati, and St. Louis.12

As the viability of Pittsburgh as a commercial center began to decline by the middles of the nineteenth century, manufacturing was quickly taking its place, finding new ways to take advantage of the nearby abundance of coal in the development of glass and iron industries. This was due to a shift in the market as well as the demand for munitions due to the Civil War that raged through the early 1860s. Pittsburgh was now turning from a once commercial city into the center for iron manufacturing in the United States. With the shift from iron to steel around the close of the nineteenth century, Pittsburgh was poised to become a center for production for the steel industry. Led by the likes of Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, and George Westinghouse (to name a few), Pittsburgh was now the center for mass production of steel, railroad equipment, and other machinery.13

With this industrialization also came Pittsburgh’s reputation as a dark and filthy city. Although often glorified and romanticized in paintings and other works of art for being a pinnacle of the industrial age, for more than a century, the unsavory aspects of Pittsburgh were as well to be documented in paintings, photographs, and writings. Writer Willard Glazier wrote that, “Pittsburg is a smoky, dismal city at her best. At her worst, nothing darker, dingier or more dispiriting can be imagined.” He went on stating that, “The city is in the heart of the soft coal region; and the smoke from her dwellings, stores, factories, foundries and steamboats, uniting, settles in a cloud over the narrow valley in which she is built, until the very sun looks coppery through the sooty haze.”14

Jack Delano’s photograph of a stairway leading from residential areas and down to the factories gives us a glimpse into how it might have felt to make the journey to and from work every day. Even though the factories are mostly gone from our skyline, the public stairways still exist today in many of our neighborhoods and we can still imagine how it might have felt to make that commute, on foot, on a daily basis.15

Long Stairway in Mill District of Pittsburgh Library of Congress Images16

Throughout this time, Pittsburgh just kept growing and expanding. During the half century between 1865 to 1915 the area witnessed the creation of some of Pittsburgh’s most ambitious manufacturing complexes. These included, but were not limited to, the steel complexes that extended out through surrounding towns on all of three of the rivers. Pittsburgh’s factories were beginning to exceed in size and scale the gigantic plants of England and Germany.17

H.J. Heinz now had his food operations based in Pittsburgh’s Allegheny City neighborhood (which would later become part of Pittsburgh’s North Side neighborhoods).18 The Alcoa plant up the Allegheny River became the world’s first complex for the production of aluminum, and PPG’s huge glass plants were located even further up river on the Allegheny while George Westinghouse was commissioning the building of his various plants in the East Pittsburgh areas of Wilmerding and Swissvale. While this was happening, George Mesta’s machinery works in West Homestead had become the world’s largest presses for cutting dies and the Jones and Laughlin company was building its ‘miles-long’ steelworks complex downstream on the Ohio in the Aliquippa area.19

These were some of maybe the best but also the most tumultuous times for Pittsburgh. Revenue was flowing into the city the city had reached a population of around 322,000 by the year 1900 (quadruple what it was only 30 years earlier). Steel production was prominent in the South Side, Hazelwood, Lawrenceville, and Strip District neighborhoods along with the corporate dominated surrounding boroughs such as Homestead, Braddock, and McKees Rocks.20

Pittsburgh was now well established as a dark and unappealing town. Because of the smoke and soot, streetlights stayed on at all times of the day. White-collar businessmen were said to often need to change their white shirts two or more times a day and surveys had put Allegheny County as having the highest rates for typhoid fever and industrial accidents in the country.21

Around this time, there was some good news from an ecological point of view. In 1889, with the donation of a substantial piece of land from Mary Shenley, Pittsburgh also saw the creation of Shenley Park, its first public park. Shenley had inherited the land from her grandfather James O’Hara but had moved to England with her husband. She had come back to Pittsburgh briefly from England when she turned twenty-one and was convinced by Edward Bigelow to donate her inherited land to the city for use as a park.22 Even in the midst of an industrial bombardment of the area, and even if they are mainly for a privileged few, we are seeing that there is some importance being put on green spaces.

The creation of these green spaces, which now included Highland Park (originally created as a reservoir) in 1893 and the Pittsburgh Zoo (Opened in 1898 within Highland Park), Pittsburgh was now also now contending with the introduction of motorcars at the turn of the century.23 Highland Park also being the name of the neighborhood surrounding Highland Park as well as being where my school is located. My school, Pittsburgh Dilworth being built in 1915 but Pittsburgh’s Fulton Elementary was built as early as 1894.24

Between the two world wars and by the middle of the twentieth century, Pittsburgh was starting to think beyond the soot and the darkness but was still completely at the mercy of the steel industry. Especially after the second world war, there were ideas being put forth from notable architects and designer firms with the most recognizable being Frank Lloyd Wright (who had designed both Falling Water and another house in nearby Fayette County). Plans were being made for the revitalization of downtown along with other neighborhoods in the city and by the 1970s, the ‘Pittsburgh Renaissance ranks as one of the most ambitious and intensive reconstructions of any city in history.25

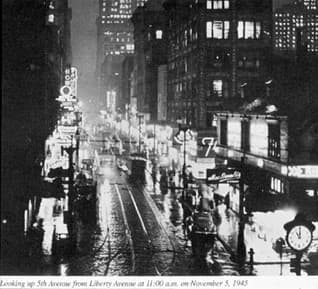

Looking up 5th Avenue from Liberty Avenue at 11:00 a.m. on November 5, 194526

Looking up 5th Avenue from Liberty Avenue November, 202027

Jump ahead a few years, and here we are, multiple decades into the twenty first century in a cleaner and greener Pittsburgh. In comparing the same views from November of 1945 at 11a.m. and a midday view from November of 2020, we can see that we have made some great strides. But when we look closer, we can see that we still have a way to go.

Most of the blatant signs of industry are gone but where does that leave us? What about the invisible particulates that still float around our valley between the hills? The smoke is gone and we can once again see the green hillsides. They aren’t quite as they were centuries ago before colonization, but they have, once again, become more of a picturesque scene instead of the apocalyptic sublime that we would have witnessed over the past century or two.

In line with being referred to as “The Paris of Appalachia”, landscape artist Ron Donoughe proclaims that “Pittsburgh is a painter’s Paradise” adding, “there’s so much variety and texture.” But where does texture and, grit, and heft leave us? We can see our history’s wealth and history in the architecture and landscapes of the region, but we are also dealing with a steep population loss as a metropolitan area coming into this new century with New Orleans being the only other major metropolitan area to lose more population, and we don’t have any major destructive floods to blame.28

So here we are moving through almost a full quarter of the twenty first century and where does Pittsburgh stand? We have made great strides to clean up our city yet according to a report released in April of 2023 by the American Lung Association, Pittsburgh still ranks as one of the worst cities in the nation when it comes to air quality and particulate material. According to the same findings from the American Lung Association, Pittsburgh moved from being the 46th worst in the nation to 54th worst in the nation in terms of pollution from ozone smog moving us from a Lung Association ‘F’ rating up to a ‘C’ rating, still poor but less poor. The most up to date findings from the Lung Association has us ranked 50 worst out of 228 metropolitan areas for high ozone days, 26 worst out of 223 metropolitan areas for 24 hour particle pollution, and 19 worst out of 204 for annual particle pollution and, although an improvement, these findings are not where we need to be.29 Even though we are more than 50 years out from our big renaissance as a city, what else can we do to finally wash ourselves of the lingering ghosts of industry?

So, truthfully, where do we go from here? What is it about Pittsburgh that makes it still such a special place? We’re not quite far enough out to be a ‘Midwestern’ city and we’re definitely not close enough to the Atlantic Ocean to be considered ‘East Coast’. Is it truly fair to refer to us as the ‘Paris of Appalachia’ or are we, with all our history, scars, and uniqueness, just Pittsburgh? And if so, I think that I am okay with that. What do you think? What’s out your window? How does the landscape look to you?

Comments: