In August of 1791, Benjamin Banneker, a naturalist and polymath, enclosed a copy of his most recent almanac to Thomas Jefferson, one of the key authors of the Declaration of Independence, later President of the country he declared independence for, and an enslaver. Banneker, a descendent of free Blacks, felt compelled to address the issue of slavery and abolitionism with Jefferson. Throughout the course of the letter, Banneker compares the struggle of the Patriot for independence and freedom against British tyranny to the enslavement that millions of Black Americans were presently enduring. The language of the Patriot cause made constant reference to a sense of enslavement and servitude to the British crown. Jefferson himself, against later opposition, included a clause blaming King George III for perpetuating the American slave trade, and accusing him of inducing a slave revolt during the rebellion. Nevertheless, the great promise made by the Declaration of Independence, “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” was a falsehood for Black people living in America.1 To a modern observer, as it was to Banneker, that the supporters of the purported ideals of freedom, liberty, and equality kept people in bondage evinced a clear message of hypocrisy. Banneker admired the standard of liberty that the Patriots set forth in the Declaration; but remarked directly to Jefferson “how pitiable is it to reflect, that altho you were so fully convinced of the benevolence of the Father of mankind, and of his equal and impartial distribution of those rights and privileges which he had conferred upon them, that you should at the Same time counteract his mercies, in detaining by fraud and violence so numerous a part of my brethren under groaning captivity and cruel oppression, that you should at the Same time be found guilty of that most criminal act, which you professedly detested in others, with respect to yourselves.”2 Sixty years later, famed orator and abolitionist Frederick Douglass asked, “what to a slave is the fourth of July?” While showing the same admiration for the principals of the Declaration, Douglass declared that “the rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me.”3 A century after Douglass’s speech and the legal end of chattel slavery in the United States, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. again referenced the language of the Declaration of Independence in his most famous speech, that “it is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned.”4 For these three men, across time periods, there was an promise made in the Declaration of Independence, and though while not a legally binding document, it illuminated the great principals of equality and freedom that the U.S. government purported to follow. At the same time, the Declaration exposed the hypocrisies of an enslaving and racially unjust nation. For Douglass, the answer was in the United States Constitution, which he “found to contain principles and purposes, entirely hostile to the existence of slavery.”5 The promises of liberty and equality found in the Declaration had a tremendous impact in the ongoing fight for justice. If literacy is seen as the pathway to freedom, as it was seen by many Black Americans in the 19th century and certainly by Douglass, then Black readings and understanding of the foundational documents of the United States is essential to carry the movement for justice forward.

In this curriculum unit, students in a sophomore Civics class will read foundational texts of the government of the United States, hoping to answer the essential question of “how did black readers, authors, and writers respond and interpret foundational texts in the pursuit of the principals of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness?” The unit will be compromised of three primary sections, each lasting between one to two weeks:

- An exploration of the texts and thinkers canonically considered to be major influences of the Declaration and the Constitution, specifically Locke and Montesquieu, especially focusing on the effects their ideas had in ideologically solidifying justifications for slavery. This will be combined with research focused on the ideological positions of the framers themselves. While this unit will be primarily focused on reading and analyzing black texts and voices, students will also understand how the ideas of Locke and Montesquieu were used to uphold the institutions of slavery and discrimination. Additionally, students will examine Black voices during the Revolution in response to the Declaration’s claims.

- Section two will examine how the Declaration was used as rhetorical tools in the movement for the abolition of slavery, with a starting point of the writings and speeches of Benjamin Banneker and Frederick Douglass. Here, students will understand how these documents were interpreted by contemporary Black thinkers and writers, as well as the glaring differences between their principals and their actions. Readings will be taken from 1776 to 1861 with a focus on the language of abolitionism. Students will also grapple with and explore the concepts of literacy and textual interpretation not only as a rhetorical device but likewise as a means to liberation. This will include readings on black literacy, as well as the laws that were designed to prevent both free and enslaved Blacks from learning to read and write.

- How the language of the Declaration has been understood in the 20th century onward, including the readings and speeches of activists in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, to contemporary readings of the Declaration of Independence in the erasure poetry of Tracy K Smith.

Throughout this unit, students will employ the strategies of close reading to interpret the Declaration of Independence as well as the Black authors and texts who interpreted and grappled with these ideas. With a unit focused on the importance of literacy, students will build their skills as both readers and writers; while understanding how essential these tools are to a healthy and functioning democracy. Each individual section will include smaller writing assignments for students to demonstrate their understandings of the texts and readings, as well as a research component included in sections two and three, where students will experience using the archive to answer meaningful historical questions. Section four will include a creative writing assignment, asking students to follow the poetic forms of Tracy Smith in their readings of these two documents. As a final project, students will answer one of the unit’s essential questions in an extended essay, where they will be asked to interpret these documents in the context of present-day challenges and politics.

Part 1: Teaching Objectives and Historical Background

The Drafting and Signing of the Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence stands as one of the most notable, memorable, and taught documents from American history. While the Constitution serves mostly as a formal document of government, writers, thinkers, and politicians have attached varieties of meanings to the Declaration, from a statement of human rights to justifications for rebellion against the British crown. Educators and students should understand the thinkers who influenced the Declaration, who were referenced both to justify independence and the continuation of the colonial economic model of chattel slavery, the deleted clauses of the declaration concerning slavery, and the perspectives of Black people, both free and enslaved, in the immediate aftermath of July 4th.

The Declaration of Independence can best be understood as a product of Enlightenment thinking, and while historians debate on the precise influences on the ideologies that shaped the Declaration, and indeed the entire Revolutionary project, Barry Bell notes that “if the Declaration of Independence can be placed in the tradition of the Scottish Enlightenment, it can also be traced to Locke, to the European Enlightenment in general (and, in particular, to Jean Jacques Burlamaqui, the French Physiocrats, and others), to the Real Whigs, to the American Philosophical Society and the shared "modern" scientific beliefs that it represented, and even, as Merrill Peterson has shown, to such anomalous figures as Bolingbroke.”6 Thomas Jefferson, the principal draftsman of the Declaration, wrote in a letter to Henry Lee in 1825 that the Declaration was “neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, not yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind.”7 While readers may not be able to track the precise influences of political philosophy on the text, Jefferson and the other drafters clearly intended the document to reflect popular, and familiar, political sentiments of the time. Moreover, the text clearly affirms the ideas of natural rights, that governments exist to protect rights, and that rebellion can be used as a remedy against tyranny. The precise influence of John Locke on the drafting of the Declaration is open-ended, but we see an obvious similarity in the assertion of the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit happiness echoes the language of Locke in his Second Treatise on Government. He writes: “the law of nature…, which obliges every one: and reason…teaches all mankind, who will but consult it, that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions”8 Locke’s language may seem to advocate for political equality, but social contract theory likewise establishes the true nature of the power relationship of slavery, one of “absolute, arbitrary power” over another and that “no man can by agreement pass over to another that which he hath not in himself-a power over his own life.”9 Locke considers that enslaved people, under the total power of their masters, can never be a part of the social contract that forms the basis of systems of government. Philosopher Charles Mills sees the extension of the Lockean contract as one foundational to modern forms of white supremacy, saying that “insofar as the modern world is shaped by European expansionism (colonialism, imperialism, white-settler states, racial slavery), it could likewise be regarded as founded on an exclusionary intrawhite ‘racial contract’ that denies equal moral, legal, and political standing to people of color.”10 Students and educators must understand that while the language of the European Enlightenment supported the freedoms of men, it is clear that they meant white men, with the social contract at the exclusion of others. As Toni Morrison writes, “we shout not be surprised that the Enlightenment could accommodate slavery; we should be surprised if it had not… nothing highlighted freedom-if it did not in fact create it- like slavery.”11 What Morrison terms “the Africanist presence,” while originally conceptualized for analyzing the literature of the American Republic, likewise speaks to the political ideals and philosophies maintained by the drafters of the Declaration of Independence. Here, then, the contradictions in language do not evince a contradiction in ideas; freedom meant clearly the white man’s freedom.

The text of the Declaration of Independence, as adopted on July 2nd, contains one notable exclusion in its drafting. Thomas Jefferson claimed later in his life that a passage from the text on slavery was excluded at the behest of the delegations of South Carolina and Georgia. The deleted passage reads:

“He [King George III] has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither…. Determined to keep open a market where Men should be bought & sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or restrain this execrable commerce12

The irony, again, is that Jefferson was a slave holder and maintained this status throughout his life. Jefferson manumitted five slaves in his lifetime, two of whom were his biological children with Sally Hemmings. Jefferson does not blame slave holders for maintaining the institution, but King George; rather than taking responsibility for manumission and emancipation, Jefferson argues that British colonialism propagated slavery. While using the language evoked in the Declaration’s opening paragraphs, Jefferson does not declare the cause of the enslaved as part of the Patriots, they are a “distant people.” David Brion Davis notes that Jefferson was largely silent on the topic of slavery later in his life, perhaps partially in recognition of the seeming contradictions.13 In this unit, students will understand these complexities and political realities that exist within the adoption and creation of the Declaration.

The Black experiences of the American Revolution

While it is important to understand the political and philosophical foundations of the Declaration, namely how those ideas could comfortably coexist with slavery, our concern is on the on the voice, writings, and experiences of Black people across American history and politics in response to this foundational document. The language of liberty for the enslaved person was very different from those, like North Carolina’s delegation to the Continental Congress, who cried out that the British intended to “overawe and enslave the other Colonies.”14 The language of slavery, of absolute power and domination, was used by those who were a very part of that institution. Shortly after armed conflict began between the colonists and the British, colonial officials and governors, looked to the enslaved to fight against their rebel owners with offers of manumission. Jefferson in his deleted passage from the declaration, accused King George of “paying off former crimes committed again the Liberties of one people [the enslaved], with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.” In the Virginia colony, Governor Lord Dunmore ordered that “all indented Servants, Negroes, or others, (appertaining to Rebels,) [are now] freed that are able and willing to bear Arms”15 Black people, both free and enslaved, did indeed fight for the loyalist cause in large numbers, with over half of the army that Lord Dunmore raised consisting of Black soldiers.16 The North Carolina delegation, aware of the possibility that enslaved people might indeed take up arms for the British in exchange for guarantees of freedom, warned their constituents of a “dangerous Enemy in your own Bosom” who would not “hesitate to raise the hand of the servant against the master.”17 In the same letter in which they feared their own ‘enslavement’ by the British crown, the authors cannot sustain a logical defense against Samuel Johnson’s charge that “the Slaves should be set free, an act which the Lovers of Liberty must surely commend.18 The actual promises of freedom prevailed over just the language and rhetoric of freedom, with enslaved Black people seeing a pathway to freedom through the British crown.

Of course, not all Black people in the American colonies at the time of the Revolution fought for the British, nor did they reject as falsehoods the promises of rights found in the Declaration. As early as 1776, Black readers and writers were already taking up, and transforming, the declaration's language from what was originally intended. Historian Jack Rakove notes that “the principle of equality that Jefferson invoked in the preamble to the Declaration had more to do with the equality of peoples than individuals. What he was proclaiming was the right of Americans, in the plural, to exercise their collective right of self-government, rather than the right of each American to enjoy a wholly equal set of liberties.”19 Reading the Declaration through this lens, we can see how its authors might attempt to reconcile slavery with the document’s statements of equality. Gradually, overtime, we see a change in the commonly held public interpretation of the phrase that “all men are created equally” to be equality for the individual, and we can see that idea begin first and foremost with Black authors. Lemuel Haynes, a free Black man and the first Black minister to be ordained in the Congregational Church, served in the Continental Army.20 Haynes read and wrote a large variety of texts, and used his knowledge of both literature and the Bible to formulate tracts against slavery. In an unfinished manuscript essay entitled “Liberty Further Extended,” Haynes takes up the form of a sermon, like other Calvinist preachers in the late 18th century, with his hermeneutical focus on the Declaration of Independence claim that “all men are created Equal.” He writes that “As Tyranny had its Origin from the infernal regions: so it is the Duty, and honor of Every son of freedom to repel her first motions. But while we are engaged in the important struggle, it cannot be thought impertinent for us to turn one Eye into our own Breast.”21 To Haynes, the language and rhetoric of the Declaration and of the Revolution are the perfect moments for all living in America to seize their liberty. He invites the reader to examine the true cause of freedom in the colonies, and to see that slavery is “much greater than that which Englishmen seem so much to spur at, which they themselves impose on others.”22 Haynes understand that the ideas of liberty and freedom are on the minds of many living in the colonies, and requires that his readers reach the same logical conclusion as he does. He writes that “an Englishman has a right to liberty is a truth which has been so universally evinced that to spend time illustrating this would be but superfluous tautology” and that following the same line of thinking argues “that even an African has Equally as good a right to his Liberty in common with Englishmen.”23 Haynes sees a common cause, that the fight for freedom, as the colonists themselves have phrased it in their rhetoric, must naturally be a universal one. Through taking up armed struggle to overcome the perceived tyranny of the crown, the Patriots are presented with an opportunity to address the plank in their own eyes. Haynes proceeds to expose the practice of slavery and the slave trade as contrary to the laws of God, and then refute Biblical justifications for slavery, addressing Paul’s exhortation for “slaves to be obedient to their masters,” writing that in other chapters “the Apostle seems to recommend freedom if attainable.”24 Haynes used the language of natural rights and liberty exactly as they were presented in the Declaration of Independence, seeing outright the clear contradictions of language and action. There is a promise for Haynes that the new republic which he fought for might truly bring freedom for all.

Others took up Haynes’ call for an end to slavery using the language of the Declaration of Independence. In 1779, Prince Whipple, enslaved to William Whipple, a general in the Continental Army and one of the signers of the Declaration, petitioned the New Hampshire House of Representatives for his freedom along with the freedom of 18 other enslaved people. Whipple was present in Philadelphia for the duration of the Second Continental Congress, and similar to Haynes, uses the language of the Declaration as an appeal for freedom. The petition claims that “the God of Nature gave [the petitioners] Life and freedom upon the Terms of the most perfect Equality with other men, That Freedom is an inherent Right of the human Species, not to be surrendered but by Consent for the Sake of social Life; That private or publick Tyranny and Slavery are alike detestable.”25 The language notes the double tyrannies present in New Hampshire: the public one of the British crown, and the private one of slavery. Indeed, this petition likewise pays homage to Locke, who wrote that a man “cannot by compact or his own consent enslave himself to any one.”26 A particularly interesting choice of words is that of “the human species” instead of man, something that is truly universal. The language and rhetoric being used here reverses the terms of freedom as outlined by Locke and the drafters of the Declaration. For the petitioners, slavery itself contradicts the laws of nature and cannot be consistent with the language of rights, freedom, and liberty. They saw the opportunity for their own freedom, and argued that by being granted their liberty, they could show “the World our Love of Freedom, by exerting ourselves in her Cause, in opposing the Efforts of Tyranny and Oppression over the Country in which we ourselves have been so injuriously enslaved.”27 The Patriot’s fight for freedom could be joint, where all can enjoy the fruit of liberty. The petitioners recognize the illegal and immoral harm which slavery has caused them, yet still offer to fight for a country whose vision of freedom would include them. While New Hampshire had very few enslaved people living there by the start of the Civil War, no law was ever passed officially abolishing slavery. Five of the petitioners were manumitted, while the remaining fourteen died enslaved. They were not the only enslaved people around the time of the Revolution to argue boldly and publicly for their freedom. Similar petitions can be found addressed to the governments of Maryland, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, and use the language of the Declaration to advocate for the abolition of slavery.28 Black voices and authors would continue to use the words of the nation’s founding document in their fight for liberation.

The Abolitionists and the Declaration

When the United States had secured its independence, and implemented the Constitution as its governing document, the hopes of Prince Whipple and Lemuel Haynes that the Declaration’s statement of human rights might be made into fabric of the country were dashed. Indeed, while the Constitution did include a provision to end the United States’ participation in the international slave trade in 1808, the institution was left otherwise untouched. As a compromise for the Constitution’s passage for southern slave holding states, the so-called three-fifths declared that enslaved people, for the purpose of the census and national tabulation, would count as three-fifths of a person. While this provision not only delegated the personhood of enslaved people as less than that of a white man, it also bolstered the political power of slave-holding states in the House of Representatives and Presidential elections. This failure of the Constitution did not detract from the movement to end the practice of slavery. As historian Manisha Sinha writes, we can see two waves of abolitionism in the United States: one starting in the 18th century around the time of the Revolution, which Sinha rightfully points out caused a tumult within the intellectual and political debates about the nature of freedom in a society which permits slavery. The second, and more well-known, began in the early to mid-18th century, where we can see an intellectual movement coalescing around bringing an immediate, not gradual, end to slavery. This movement would be spearheaded by prominent figures like Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and William Lloyd Garrison. As we analyze and interpret the cause for the immediate abolition of slavery in the United States, it is essential that we remember Sinha’s essential statement that “slave resistance, not bourgeois liberalism, lay at the heart of the abolition movement.”29 This is not to say that there are not valid critiques of American abolitionism, but too often Black voices are lost in the historical dialogue about abolitionism. Let us return for a moment to Benjamin Banneker, the Black polymath we were first introduced to in the introduction. Scholar of education LaGarret J. King argues the status of Banneker as a “Black Founder,” one who established institution to essential to Black communities, and “challenged the supposed egalitarian beliefs of White Founders through media outlets.”30 King’s assertion here is to push back against much of the way Black history is taught in American social studies courses, relegating Black historical voices as only those of the enslaved, voiceless in bondage. Banneker helps us fight against these narratives, to understand that Black authors and voices were challenging white supremacy from the very beginning of the American republic. Just as Banneker and Frederick Douglass used the declaration of Independence as an historical tool, so too would countless other Black abolitionists. It is through the writing of Black authors and abolitionists that we begin to see a subtle shift with the public interpretations and memorializations of the Declaration of Independence. Historian Michael Hattem (and Associate Director of the Teacher’s Institute, to whom I owe many thanks for letting me read an advanced copy of his book) writes that “for Garrison and many of his fellow abolitionists, the core meaning of the Revolution was defined not by stories of heroes or even ordinary soldiers by its ideals, particularly as expressed in the Declaration. For two decades after independence the Declaration was not seen as especially important. To most, it symbolized national independence.31” During the years leading up to the Civil War, Americans would become increasingly attached to the political philosophy of the Declaration of Independence, at times holding it above the Constitution as the central promise of American democracy. The efforts of writers like Benjamin Banneker would inspire the abolitionists to embrace the holistic meaning of the Declaration, in a struggle to truly bring equality to all. In this intellectual construction of the Declaration in the mind and rhetoric of the abolitionists, the Declaration for many became a promise and a real statement of political philosophy and ideals. We will see this viewpoint extended into the 20th century as one that will remain consistently active.

Several modes and examples of the rhetorical and intellectual use of the Declaration of Independence can be found in the writings and oratory of abolitionists. The Declaration of Sentiments of the American Anti-Slavery Society stated that in their pursuit of immediate abolition “we plant ourselves upon the Declaration of our Independence and the truths of Divine Revelation.” The Anti-Slavery Society, composed of Black and white activists alike, saw their philosophical foundation planted entire in the principles stated in the Declaration of Independence. Specifically, they saw the defining phrase of liberty and equality as “the corner-stone upon which they founded the Temple of Freedom”32 While perhaps not giving this phrase precise legal credence, even acknowledging the difficulties of the form of the Constitution in limiting slavery by law, Garrison, the primary author of the Society’s Declaration, clearly saw it as foundational to the national political and civic character. For Hosea Easton, a Black preacher and abolitionist in Hartford, he saw that the Declaration was in part a legal guarantee for both immediate abolition and equal citizenship, writing that the Declaration (and, interestingly, the Article of Confederation) were “sufficient to show the civil and political recognition of the colored people. In addition to which, however, we have an official acknowledgment of their equal, civil, and political relation to the government.”33 Easton extends that same logical line of thinking as seen in the Declaration of Sentiments that the principles of equality and liberty as defined in the Declaration of Independence do have philosophical, if not legal, standing. Indeed, as the enslaved captives of the Amistad waited in a New Haven jail for the legal decision of the Supreme Court determining if they were free or not, John Quincy Adams used the Declaration of Independence several times while arguing the case.34 Easton calls out the real contradiction between what he sees as the nation’s principals and its reality, writing that the states “ought to have perjury written upon their statute books, and upon the ceiling of their legislative halls, in letters as large as their crime, and as black as the complexion of the injured.”35 Throughout the rhetoric of Black abolitionists, we see this same sort of anger and disillusionment with the failed promises of the Declaration. In “What to the slave is the Fourth of July?” Douglass provides a more biting and scathing criticism of the document than we see otherwise from the abolitionist writings and rhetoric. In the first part of the speech, delivered to a mostly white audience, Douglass praises the Revolutionary spirit, of a people dedicated to fighting against tyranny, but notes “the freedom gained is yours.”36 Throughout the entirety of this part, Douglass uses second person pronouns to describe the freedoms and liberties symbolized by the celebration of the Fourth of July. He sees that he is not a part of those promises. While Easton saw the Declaration as a failed promise, Douglass considers that Black people, both free and enslaved, were not even considered in the first place. He says that to the slave “your celebration is a sham…There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.”37 Douglass’ hope, then, came from the Constitution, because that document can be amended and changed in the hopes of living up to the ideal of a more perfect union. Rather than look to the past, Douglass looks to the future instead.

The abolitionist movement shared common cause with the push for women’s rights in the 19th century, and often an abolitionist is also a suffragist. Similarly, we see a tremendous amount of overlap in styles of rhetoric, with activist in both movements frequently referencing the Declaration of Independence frequently. The meeting of the Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls in 1848, including abolitionists like Frederick Douglass, published their Declaration of Sentiments, which very purposefully imitated the language, organization, and structure of the Declaration of Independence:

When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one portion of the family of man to assume among the people of the earth a position different from that which they have hitherto occupied, but one to which the Laws of nature and of nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires, that they should declare the causes that impel them to such a course. We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal.38

The remainder of the text follows the exact same pattern and organization as the Declaration of Independence, and levying charges of injuries and usurpation not against the British king, but “on the part of man towards woman.”39 Creating this new Declaration insinuates that first intended only men as holders of rights. The Declaration of Sentiments is at once an homage to the ideals promulgated in the Declaration of Independence, an acknowledgement of its failures, and a promise to fulfill that promise anew. Other suffragists use the exact same rhetorical references to the Declaration, like Sarah Grimke who wrote “that man and woman were created equal, and endowed by their beneficent Creator with the same intellectual powers and the same moral responsibilities.40” Through this rhetoric, authors hoped that their American readers would recognize all the apparent contradictions found within the Declaration of Independence. And for many, like Sarah Grimke, the cause for women’s rights and abolition were founded on the same ideals. She writes that “tears, unaided by effort, could never melt the chain of the slave. I must be up and doing.”41 Grimke’s words offer sound advice to how we might approach the social, political, and moral problems of today, where ‘thoughts and prayers’ must be accompanied with purpose and action. One of the essential aims of this unit is for students to understand how people approach activism, organize, and put words and ideals into meaningful action.

Black women were essential to the causes of both abolition and women’s rights, and we can see clear overtures to the Revolution and the Declaration of Independence in their speeches and writing. When Sojourner Truth stood to speak at the Woman’s Convention in Akron, Ohio in 1851, asserting her equal status with men and whites alike, stated that “man is in a tight place, the poor slave is on him, woman is coming on him, and he is surely between a hawk and a buzzard.”42 Here, Truth explicitly connects the causes of abolition and Charlotte Foten Grimke, niece to Sarah Grimke and daughter to a free Black woman, shows evidence of this even in her journal. While attending a school in Salem Massachusetts after being refused a public education in her home city of Philadelphia, she followed closely the trial of Anthony Burns, who had escaped from captivity but was imprisoned under the Fugitive Slave Act. Grimke was heavily involved in the abolition movement, detailing her work exhaustively. When Burns was forced back into slavery, she writes:

“With what scorn must that government be regarded [that] deprives of his freedom a man, created in God’s own image, whose sole offense is the color of his skin… And if resistance is offered to this outrage, these soldiers are to shoot down American citizens without mercy; and this by express orders of a government which proudly boasts of being the freest in the world; this on the very soil where the Revolution of 1776 began; in sight of the battlefield, where thousands of brave men fought and died in opposing British tyranny, which was nothing compared with the American oppression of today.43

Her outrage echoes the pointed criticisms that Douglass gave in “What to a Slave is the Fourth of July?” She connects the history of Boston and Massachusetts to the American Revolution and marks the American tyranny of slavery as farce worse than any the British inflicted. The commonwealth of Massachusetts failed to uphold its purported principles, insinuating that the work of abolition and women’s rights might fulfill the promise in the public memory of the Revolution.

As the movement for immediate abolition gained power and traction, we see an equal amount of investment from both free and enslaved Blacks into education. While this looked very different in Northern cities than on Southern plantations, both groups faced severe challenges, as the white slaveholding class understood that literacy was a pathway to freedom and resistance. This section is not dedicated to just the readings of the Declaration, but why literacy and education were so fundamental to the cause of abolitionism and resistance to slavery.

For enslaved Blacks, learning to read was potentially deadly, as most slave states had some law forbidding literacy. Enslaved people would often meet in secret or use clever and subversive tactics to glean literacy skills from their enslavers. Consider, for example, the case of Thomas Johnson, who “met secretly for Bible study with other Richmond black people who could read. As he recalled later, the chapter they studied most was Daniel 11, whose prophecies they interpreted to predict the ultimate triumph for the Northern army over the South.”44 Here, we see firsthand how Black readers interpreted the texts they read and envisioned their own freedom and triumph into them. Sometimes, enslavers would even teach the enslaved to read, as happened with Frederick Douglass; however, as Heather William points out, “whites feared that literacy would render slaves unmanageable. Blacks wanted access to reading and writing to attain the very information and power that whites strove to withhold from them.”45 This was the case with Frederick Douglass, whose mistress abandoned teaching him upon the admonition of her husband that reading would make Douglass more rebellious. Hearing the anger and fear from the slave-owner only inspired Douglass further, who recollected that “from that moment I understood the direct pathway from slavery”46 In literacy, Douglass saw the prospect of freedom, and applied himself diligently to his studies. He took particular interest in The Columbian Orator, a sort of textbook and anthology of famous (mostly) political speeches and dialogues. The compiler, Caleb Bingham noted that the choice of speeches was to inspire pupils of the young Republic with “the ardor of eloquence and the love of virtue.”47 The act of reading this book was an act of resistance, not just in his violation of the prohibition of literacy, but likewise through engaging in this text intended to build up civic virtues in the young country. Douglass would one day hone his skills as an orator on behalf of the abolition of slavery and the rights of women. In the Orator, Douglass found the pathways to freedom in the speeches of Richard Sheridan on Irish emancipation and of Charles Fox and William Pitt the Elder on the American Revolution (it is worth noting here, for reasons that deserved to be explore further, that Douglass’s highlighted readings from the Columbian Orator come exclusively from English, not American or classical, speakers.) According to Douglass, the most impactful was the “Dialogue Between Master and Slave” written by John Aikin. In the dialogue, the enslaved person convinces his enslaver to free him, stating that “it is impossible to make one, who has felt the value of freedom, acquiesce in being a slave.”48 To Douglass, the act of reading was the direct path to true freedom, and the experience of reading here was his first meaningful taste of it. Of the experience, he writes that “I could not help feeling that the day might come, when the well-directed answers made by the slave to the master, in this instance, would find their counterpart in myself.”49 Douglass would end up doing exactly that to an entire nation of slave holders.

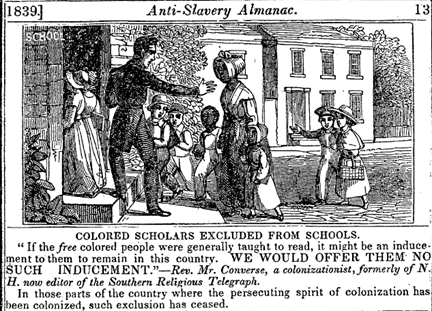

In the North, the Black push for literacy was centered around the establishment of institutions of learning, as free Blacks were denied access to public schools and universities. As David Blight notes, “nothing motivated this Black self-improvement formula quite like the quest for schools.”50 As Southern slave states passed laws prevent Black people, both free and enslaved, from learning to read, so too did Northern states bar access to institutionalized education. For many political moderates in the North, the solution to the problem of slavery was not immediate abolition and integration into society, but colonization. The idea behind this scheme was to organize and send free and manumitted Blacks to Africa, rather than to grant them rights as citizens in America (this was how the country of Liberia was founded.) For the most part, Black communities and abolitionists were against the idea of colonization, and the fight in the broader public became between colonization against education (see Figure 1.) Indeed, this was the case in New Haven, where efforts to establish the first college for Black Americans were proposed in 1831.51

Figure 1 –A sketch on education being denied to Black people. Note the quotation from the supporter of colonization.52

In New Haven, Peter Williams and Simeon Jocelyn spearheaded the movement, and garnered support from abolitionists and free Blacks across the North. Some of the arguments in favor saw education as fulfilling the promises of the Declaration of Independence, as one writer argued that “time and circumstances may affect the expediency of the case but cannot alter the essential principals of the Declaration of Independence, and of divine law.”53 In another text of support, featuring imagined dialogue, personified a public hesitant to the idea of a Black college and of a Black man who might “feel himself almost equal to whites;” the response of a voice named only ‘a friend’ declares reads “why not equal? Does not our Declaration of Independence declare that all men are created equal?”54Literacy and education, were essential part of the project of true equality as promised in the Declaration for these writers. Unfortunately, the ruling elite in New Haven were opposed to the idea, with Blight writing that “Indeed, Yale’s ethos at this time was colonizationist at best on the slavery issue, and the idea of a Black college in their own neighborhood violated such aims.”55 The fight for a Black college might have failed in New Haven, but that did not stop Black people from educating themselves and their communities.

Cashing in the Check – Civil Rights Movement to the present day

It was only through the Civil War that brought the aims of abolitionism into reality. Abraham Lincoln in his Gettysburg address saw the war’s purpose as fulfillment of the promises of the declaration. He speaks of a nation “conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” with the war was as a test of “whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.”[56] This view became popular with many of the abolitionists, and even Frederick Douglass’s views on the Declaration evolved post-emancipation. In a speech in Maryland after the Emancipation Proclamation and the banning of slavery in the state, Douglass said that “Thomas Jefferson, looking upon slavery, said he trembled for his country, when he reflected that God was just, and that his justice could not sleep forever. In getting rid of slavery, you have placed the State of Maryland, in harmony with the views and wishes, of the noblest of the national fathers, and what is far more important, in harmony with the eternal laws of the moral universe.”57 The ideals of the Declaration were not We see a similar strain of thinking pass into the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and onwards, although we also see plenty of thoughtful and critical challenges to the ideals and context of the Declaration of Independence. We will explore the ideas of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X in the 1960s and bring our examination of Black readings of the Declaration to a close with Tracy K. Smith. To keep this unit manageable in its scope, I must acknowledge a significant gap in our timeline, as surely there are plenty of readings to the time of Reconstruction and the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and teachers are encouraged to continue this research for their own classrooms.

During the March on Washington in August of 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered perhaps the most famous speech in American oratory, “I have a Dream.” King centers the first part of the speech around the idea that “When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir.”58 By using the metaphor of the Declaration as a check, King highlights the sense of obligation that its promises and ideals have. It has real meaningful purpose, which Black Americans are entitled by both law and right to demand. King’s present moment “is the time to make real the promises of democracy.”59 Just as it was in 1776, sees the Declaration as a call to action, like how the Grimkes saw it in the 19th century. Plenty has been said on the power and importance of the oratory of this speech, and its legacy remains in classrooms today. A year earlier in New York, on the centennial of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation (which he likewise refers to in his “I have a dream” speech, King stated:

“If our nation had done nothing more in its whole history than to create just two documents, its contribution to civilization would be imperishable. The first of these documents is the Declaration of Independence and the other is that which we are here to honor tonight, the Emancipation Proclamation. All tyrants, past, present and future, are powerless to bury the truths in these declarations, no matter how extensive their legions, how vast their power and how malignant their evil.”60

King sees the two documents as deeply related, with the Emancipation Proclamation in part fulling the truths of the Declaration of Independence. In them, he sees a call to action, like the one delivered in August 1963. The truths are a rallying cry, and an eternal statement of rights that should guide the shape of the country.

Among the other most taught activists of the Civil Rights movement, Malcolm X takes a different approach from King to the Declaration of Independence. While we do not have direct commentary on his views on the Declaration, his speeches and political ideology give us plenty of material to work with. In a speech given while still a member of the Nation of Islam, he asks the audience to “look at the American Revolution in 1776. That revolution was for what? For land. Why did they want land? Independence. How was it carried out? Bloodshed.”61 His historical reference to the Revolution is more to acknowledge the same purpose in Black Nationalism, for Black people to have their own country acquired through armed Revolution is necessary. He sees the American Revolution as one of what he terms white nationalism, with its purpose establishes a homeland for its white, and not its Black, citizens. In his first full press statement on March 12 of 1964, shortly after his break with the Nation of Islam, has been since titled as “A Declaration of Independence.” This could refer both to his own independence from the Nation of Islam, but likewise to the fulfillment of true justice for Black people. In this speech, he declares that his purpose is to improve the lives of Black Americans in the country in the present moment, rather than just working for the long-term goal of a return to Africa as supported by the Nation of Islam. He says to his audience that “we should be peaceful, law-abiding—but the time has come for the American Negro to fight back in self-defense whenever and wherever he is being unjustly and unlawfully attacked. If the government thinks I am wrong for saying this, then let the government start doing its job. ”62 The speech mirrors many of the justifications that the American colonists had in their war against Great Britain, with the idea that if a government does not uphold its obligations, the people have a right to replace that government through armed conflict. A week later, he takes the idea even further when he says “if we don't do something real soon, I think you'll have to agree that we're going to be forced either to use the ballot or the bullet.”63 His views have transformed since outright calling for Revolution in December of 1962, but he still advocates strongly for the idea that resistance to injustice should be peaceable if possible, but destructive if necessary: the very same principles outlined in the Declaration of Independence with violence against tyranny the final resort.

The 1970s did not bring the end to the push for Civil Rights and the quest for racial justice. In the current American landscape, organizers from movements like Black Lives Matter and the Black Coalition for Civic Participation still push for justice. In schools and universities as well as in activism and civic sphere, readers are contextualizing and evaluating America’s past in critical ways. We can see this in the poetry of Tracy K. Smith, as she highlights both present day concerns and historical injustices in her poem “Declaration.” Using erasure poetry, where lines from a text are moved, cut, and copied to create new meaning, Smith’s poetry share a powerful message:

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms:

Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury.64

Like many before her, from Lemuel Haynes and Benjamin Banneker, the women and men at Seneca falls in the Declaration of Sentiments, and Dr. King, Smith sees the Declaration as failing in its promises. Unlike those writers, she does not include the phrase “all men are created equal,” further highlighting her discontent with the present state of American politics. Those truths, as Smith phrases it in her poem, are omitted from the present reality. Her usage of the Declaration speaks to its enduring qualities and presence in the American civic imagination The Declaration of Independence was the United States’s foundational document. Over time interpretations have changed and altered: it was a justification for war against Britain, a statement of political ideals and philosophy, a promise for a brighter future for the country, or a failure to live up to its rhetoric.

Comments: