Teaching Strategies

Length of Unit

This unit was designed for sophomore-level, high school English. A typical Shakespeare unit takes four to six weeks to complete in the high school classroom, with classes meeting daily for 54-minute periods. All reading of the text occurs in class. Writing and research may take place out of class as homework assignments, but can also be incorporated into class time.

Teaching Goals

Upon completion of this unit, students will be able to analyze how the complex character of Richard III develops over the course of the play—from subversive villain to brutal tyrant to determined soldier—through an examination of Richard's speeches and soliloquies. Additionally, students will examine Richard's interactions with other characters (especially Lady Anne, Margaret of Anjou, and Elizabeth Woodville) advances the plot and develops the themes of power, corruption, and evil. 5

Students will analyze how and why Shakespeare chooses how to structure the text of the play, manipulate time through pacing and flashbacks, to create tension and suspense. 6

Students will analyze how Shakespeare draws on and transforms source material in Richard III, especially considering the untruths and distortions between the fictional and historical Richard IIIs. 7

Students will initiate and participate effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher-led) with diverse partners on grades 9–10 topics, texts, and issues, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively. 8

Students will draw evidence from literary and informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research on both historical and literary characters. 9

What is Biography?

The words of the biography allow the subject to live and breathe, to stay young forever, but it can also be problematic if the biographer insists on being a flatterer or a critic. Biography is a detailed, descriptive account of someone's life, generally from birth to death. Blending history and storytelling to create a compelling, intimate look at those who came before us, biography is as much a story about the history as it is a story about a person within that time period.

Biographer Hermione Lee has provided several metaphors to express the concept of biography: biography is a literary autopsy, examining the person—usually after death—to "investigate, understand, describe, and explain what may have seemed obscure, strange, or inexplicable." 10 Equally, biography is also a portrait made of words instead of paints: "portrait suggests empathy, bringing to life [and] capturing the character. The portraitist simulates warmth, energy, idiosyncrasy, and personality through attention to detail and skill in representation." 11 A good biographer makes both the subject and the historical period come alive within the pages of the text.

Why Study Biography?

There are many things to consider here: why do some people become famous? Who changed our world? Who makes us think? Who inspires us to grow or to change, to become better? In studying biography, we can look at people who have made profound impacts on our world and our history. As biographer Mary Marshall stated:

Partial as biography can be, it is still the best tool for bringing a wealth of issues into play in one historical work. Biography comes as close as any genre can to capturing the sense of what it felt like to be alive, in all the complexity that word suggests, at an earlier time…Biography reminds us "how certain ideas that we now take utterly for granted were once dramatically new, and how the force of them hit each person one at a time." 12In the classroom, teachers are forever searching for ways for students to become enthusiastic about what they read. Everything we like to read they find old, dull, and completely removed from their reality of technology and modern woes, not realizing that humanity has the same desires, the same worries, the same joys, and the same fears as we've always had: Will I fall in love? How do I fit in? What am I supposed to do? What happens next?

To begin the unit, students might consider the difference between writing one's own autobiography or memoir, having one's best friend write the story as biography instead, having one's worst enemy commission the story, and having a neutral third-party write the story either now or a hundred years from now. Ask students: What are you going to leave behind? What will your future biographers find and how will it be interpreted? Remember, our students are documenting everything: from selfies, or photographs of themselves on a daily basis, to hourly status updates on Facebook, and multiple tweets and texts. Additionally, they might be keeping a blog or a Tumblr account in addition to the average detritus—school records, hospital records, church records—we all accumulate in modern culture.

Why Study Shakespeare as a Biographer?

Shakespeare is not usually taught as being a biographer—English teachers prefer to teach him as a playwright and poet—but his histories tell the stories of important men from an important time of England's development as a nation and empire. Shakespeare's ability to create memorable, enduing characters means that most of what modern audiences think we know about Richard III comes from Shakespeare's play. The five-centuries dead monarch is seen as a scheming, manipulative, ugly hunchback. With little surviving evidence, five hundred years' worth of audiences from around the globe have tried this man and found him guilty of treason, regicide, fratricide, infanticide, and uxoricide.

Shakespeare's plays detailed the lives of fictional and nonfictional beings: Antony and Cleopatra, King Lear, and Macbeth are all examples of real people that Shakespeare transformed from the source material. His attraction to writing about these men and women is clarified in Hamlet, in Hamlet's conversation with the First Player before the performance of The Mousetrap: "the purpose of playing, whose end, both at the/first and now, was and is, to hold, as 'twere, the/mirror up to nature; to show virtue her own feature,/scorn her own image, and the very age and body of/the time his form and pressure." 13 Shakespeare was first and foremost a storyteller, but eliminate the iambic pentameter, disregard the supernatural, pay no attention to the crowns: at their core, Shakespearean plays are about an elemental fascination what it means to be a human being.

Shakespeare's histories—of which there are ten in his oeuvre of thirty-seven plays—were a way of teaching England about its national heritage. Much as American audiences embrace films like Steven Spielberg's 2012 film Lincoln and Roger Mitchell's film from that same year Hyde Park on Hudson, Elizabethan audiences were curious about their past. Elizabethan audiences, who did not have access to a free and public education, learned about some of their more influential kings through the theatre. Shakespeare devoted a portion of his talent towards preserving the life stories of England's monarchy. Granted these stories were greatly embellished and often acted as pieces of propaganda, but they also gave the English a sense of national pride and a consciousness of their origins.

A person's biography becomes one's pathway to immortality simply because literature has the potential to last throughout the ages. As Shakespeare wrote: "So long as men can breathe and eyes can see/So long lives this and this gives life to thee." 14 While it is true that not every piece of writing can or will last—something popular today can become old-fashioned within a generation—there is always the potential of being preserved and handed down through the ages.

Shakespeare's words and works have withstood the test of time because he tapped into the classical approach of asking big question and exploring big ideas. His writing achieved immortality because he reflected upon the nature of the human condition, he examined simple truths about big concepts like love and jealousy, and because he is difficult. He challenged his audience in 1592 not because he was writing in iambics, but because he made his audience question, think, debate, and get angry. He made them smile, boo, laugh, and cry. The human condition does not change and that is why his works have been translated into every language, performed on every continent (well, maybe not Antarctica). They are performed in Elizabethan dress and set in Elizabethan times, but they are also frequently updated into modern settings and performed in modern dress, all while retaining the beauty and poetry of the original text.

Literary Analysis: Start with SOAPSTone

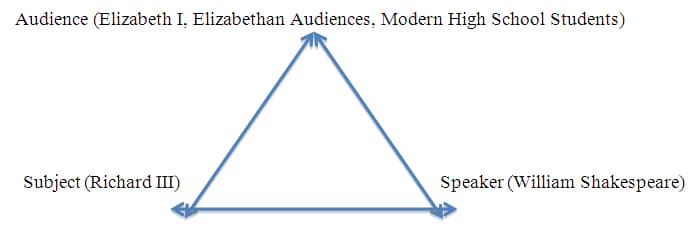

Once students have mastered the ability to recount simple details of a plot, it's time to move them up Bloom's Taxonomy from knowledge/comprehension towards analysis/evaluation. The SOAPSTone (speaker, occasion, audience, purpose, subject, and tone) strategy provides them with the first few tools in their repertoire, providing them with something to look for and discuss.

SOAPSTone is a mnemonic acronym for a series of elements that careful readers should examine as they analyze literature. 15 This strategy encourages readers to move beyond the plot and consider the speaker (not the writer, but who is telling the story?), occasion (why was this written?), audience (to whom is the piece intended? Who is supposed to read it?), purpose (what is the reason for the writing of this text?), subject (what is this piece about?), and tone (what is the attitude of the writer?) as elements that will ground the piece. It provides clarity and focuses the reader to seek evidence before interpreting the piece. In general, SOAPSTone works best with short, contained pieces of text—a poem or a monologue—but for this unit, we will be applying the first triangle of the strategy—subject, audience, and speaker—to the play, saving purpose, occasion, and tone for a second layer of analysis. This will allow students to focus on the fundamental relationship between the writer, the reader, and the topic.

The First Triangle: Subject/Audience/Speaker

Relationship between Subject and Audience: Richard III and Elizabeth I

The relationship between the subject and the audience is one that is rarely questioned: I'm here to see a play; entertain me! But this relationship would be one that Shakespeare would have carefully considered and structured, considering his primary audience was always his queen; his goal with her was always to entertain and flatter.

In 1483, Elizabeth I's grandfather, Henry VII, defeated Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field. If this was not a justified act, it was an act of treason. And if it was an act of treason, Elizabeth I should not have been on the throne. Her ascension had already been one of great dispute: the Church, her older sister, and a sizable chunk of England had questioned the legitimacy of both her parents' marriage and Elizabeth's birth. If Elizabeth I's claim were rightful, then Richard's claim must have been wrongful. The wrong king on the throne was disastrous, so Henry VII, through the Divine Right of Kings, vanquished the evil from the land, decisively ended the War of the Roses, restored England to peace, and ushered in the prosperous Tudor Dynasty culminating in the righteous reign of Elizabeth I.

Relationship between Subject and Audience: Richard III and Elizabethan Audiences

At best, the vast majority of the Elizabethan audience was undereducated. The Anglican Church provided a means to improve literacy by translating the Bible and the Mass from Latin into Common English, but it did not teach its population to question. Indeed, questioning authority usually led to trouble, imprisonment, and execution. Therefore, most Elizabethans would not question or critique a play that served to maintain the popular propaganda. Written over 100 years after the death of Richard III, there would have been no remaining witnesses to the actual reign of the king, no one to stand up for his character and suggest that the representation of the former monarch was flat or one-sided.

Besides the Church, another avenue of educating a large populace was through theater. Greece had done so in the Golden Age; the Catholic Church continued the tradition in the Middle Ages. The five-act play provided an opportunity to teach Elizabethan audiences morality, spirituality, and what history they should unquestioningly accept and embrace. In the case of Richard III, the oversimplified history taught England that the Tudors were good, the Yorks were bad; Henry VII was a hero, Richard III was a demon bent on destroying England. Richard III needed to be seen as the bad guy, not only to appease Elizabeth I, but to satisfy the original 1592 audience of this play.

Relationship between Subject and Audience: Richard III and High School Students

Why should students care about a long-dead king who ruled for two years in a country thousands of miles away? The 2012 discovery of the gravesite gives educators a hook: two-year hunt might appeal to a sense of mystery and intrigue, the twisted remains to a sense of the macabre.

But it might also be a sense of injustice that grabs hold of students' attention. My unit for Richard III typically follows a unit on Sophocles' Antigone, which deals with a body that is left unburied. While Richard III's body was given burial, he was only granted the barest minimum of dignity. His legacy, on the other hand, wasn't even afforded that much. Scholars, historians, and a certain playwright distorted the truth and trashed a man's reputation. Modern audiences are intrigued by Richard's cruelty—he's not too different from Muammar Gaddafi or Idi Amin. Perhaps not as worldly yet, modern students are intrigued by Richard III's manipulation of people, the media, and emotions. Richard III is an incredibly accessible play because of the soliloquies, allowing the audience to become, in a sense, his confidante. He tells us everything he's going to do—

"And therefore, — since I cannot prove a lover,/To entertain these fair well-spoken days, —/I am determined to prove a villain,/And hate the idle pleasures of these days," commits these heinous crimes, and then turns right back to us almost as if to gloat, and then later unburden himself. 16 Students can easily be drawn into that relationship and enjoy the exploration.

Relationship between Audience and Speaker: Elizabeth I and William Shakespeare

Elizabeth I was an absolute monarch with ultimate, unquestioned control over her kingdom. This not only extended over land and sea, but reached into every theater and artist's residence. Her approval of Shakespeare's subject matter and treatment was required for his ability to work, regardless of whether or not she would ever see the play performed.

A writer in her own right, she enjoyed poetry and theater, Shakespeare being a favorite if evidenced by the fact that she "[attended] the very first performance of A Midsummer Night's Dream." 17 Like Shakespeare, Elizabeth I was a student "of the ancient classical period; she used her influence in the progress of the English drama, and fostered the inimitable genius of Shakespeare. In regard to her taste for the ancient stage, Sir Roger Naunton tells us 'That the great Queen translated one of the tragedies of Euripides from the original Greek for her amusement.'" 18 When Richard III first premiered in 1592, Elizabeth I had been on the throne for thirty-four years. Though she did not visit public theaters, Shakespeare would have had no choice but to honor and flatter his queen if he expected her approval, her protection, and her patronage.

Shakespeare would have used the approved history of the Tudor claim to the throne. Since history is written by the victors, Shakespeare built his play on the version of events that made Henry VII, Elizabeth's grandfather the righteous winner at the Battle of Bosworth and the rightful heir to England's throne. Knowingly or unwittingly, Shakespeare built upon an accepted history to create what would become enduring propaganda for the Tudors.

Relationship between Audience and Speaker: High School Students and Shakespeare

Modern students have difficulty with Shakespeare's oft-invented words, with his iambics, with his use of the soliloquy. The challenge is getting students to see their connection to a 450-year old writer and their own, modern lives. Students see Shakespeare's style as Old English instead of Modern (differentiated from Present Day) English. American high school students distance themselves further by seeing nothing of interest in stories about English kings.

But even in the histories, Shakespeare was not merely exploring the monarchy; he was examining questions of power, loyalty, and legacy. All of these are big, essential questions for any generation, any culture. These are some of the reasons why Shakespeare's plays have endured for five centuries. Students understand the desire for power, they seek loyalty from their circle of friends, and they are beginning to wonder how they will be remembered.

Relationship between Speaker and Subject: Shakespeare and Richard III

A lot of what modern audiences think they know about Richard III comes from William Shakespeare. This play endured and is vastly more accessible than researching actual historical evidence, especially since much of the original evidence—the gravesite, undoctored portraits—was either destroyed by Tudor supporters or lost to time. Shakespeare added to the popular propaganda by creating an evil king: a hunchback with a withered arm who had spent two years in his mother's womb, who wooed his wife over the bleeding corpse of a man he helped kill, and who had orchestrated the execution of his brother in the Tower, the murders of his own nephews to secure the throne, and the suspiciously timed death of his wife, Lady Anne.

Shakespeare created an archetypal villain: the cockatrice without conscience, the monster who craved unquestioned power, the man with an unnatural relationship with his family. What Shakespeare did not do is create a forgettable character. At turns funny, charming, and fearless, Shakespeare's version of Richard III is neither easily-ignored nor easily-dismissed. In turn, he constructed a history that quickly became an accepted version of truth.

Comments: