Mathematical Background

In thinking about how to help my students understand the manipulation and solving of equations, I consider two major categories. First, the essential prerequisite knowledge for basic algebraic thinking, and second, the essential strategies or skills (sometimes referred to as “tricks”) needed to successfully manipulate and solve equations. However, before going into either of these, it is worthwhile to explore some common mistakes I’ve witnessed in student work indicating the need for further emphasis in the development of algebraic reasoning.

Misunderstandings in Algebraic Reasoning

I have encountered a series of common mistakes when students possess a limited sense of algebraic reasoning. The following represent a collection of common errors I have seen in my classroom.

Misunderstanding the Use of the Inverse

|

Example of Student Thinking |

Explanation |

|

2x=8 2x-2=8-2 x=6 |

This misconception shows that the student does not understand the purpose of using an inverse operation. In this instance the goal would be to transform 2x to x (or equivalently 1x, the multiplicative identity of two time x, by multiplying by ½, the multiplicative inverse of 2). Instead the student subtracted the two, clearly misunderstanding the purpose and possible use of inverse operations. Additionally, this may indicate that the student does not understand the notation of the term and that the 2 and the x written side by side indicates multiplication. |

|

x-4=2 x-4-4=2-4 x=-2 |

Again, this example demonstrates that the student lacks an understanding of the inverse operation. In an attempt to change -4 into its additive identity, 0, the student subtracts four from each side. This will not result in zero, however, as -4 – 4 = -8. Of course, this may also represent an error in integer operations. |

Misunderstanding the Distributive Rule

|

Example of Student Thinking |

Explanation |

|

2(x+2)=8 2x+2=8 |

From this example, it is clear that the student does not understand that the parentheses indicate that the 2 multiplies the sum of x and 2, rather than just the x. |

Misunderstanding of the Properties of Equality

|

Example of Student Thinking |

Explanation |

|

2x+1=10 2x/2+1=10/2 x+1=5 |

This student attempted to isolate the variable by dividing both sides of the equation by the same value. The student’s mistake, however, is that they have only divided the term 2x by 2 as opposed to the entire expression 2x + 1. They have therefore not imposed the same operation on both sides and the equation is no longer true. This additionally demonstrates a broader lack of understanding as to putting together the properties of equality to solve an equation as well as an additional example of misunderstanding the distributive rule. |

|

4x+2+x=10 (4x-4x)+2(x-4x)=10 2+(-3x)=10 |

This example also shows a misunderstanding of the properties of equality. This student, eager to eliminate the term 4x, subtracts it twice, once from 4x and once from the term x. This fails to account for the fact that both 4x and x are on the left side of the equation and they have therefore subtracted 4x from one side of the equation twice, destroying the equality. This also shows a lack of understanding of the utilization of the commutative and distributive rules and their role in combining like terms. |

Essential Knowledge

When considering equations, it is first essential that students understand the difference between a variable, a constant, an expression and an equation. Students will also need to know when a number or set of numbers represents a solution to an equation and when it does not.

Parts of an Equation

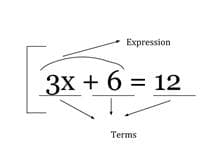

Students will need to know what makes up an equation. An equation is a statement that two expressions are equal. When one or both of the expressions have a variable the equation is essentially asking for what value(s) of the variable(s) is the equation a true statement? A value that makes the equation true, that is, does give the same value to both expressions, is called a solution to the equation. Take for example 3(x+2)=12, this is by definition an equation and x=2 is a solution to this equation.

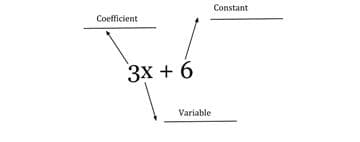

Within the expression, you may have a variable (a letter used to represent a value), a coefficient (a number multiplied by a variable), and a constant (a number on its own with no variable).

Terms can be either variables, variables with coefficients or constants. Terms are combined by mathematical operations, such as addition or division, to make expressions.

Equivalent Expressions

Different expressions can represent the same quantity. Expressions are considered equivalent when the same number(s) is substituted for their variable(s), both expression yield the same result.

Example: 2(x+4) and 2x+8 are equivalent expressions

We can check if these are equivalent expressions by substituting the same value for x in both equations and determining if the result is the same. Let’s try 3.

2 (3+4) = 2(7)=14

2 (3+8) = 6+8=142

The result was the same for both when x = 3. However, in order to be equivalent expressions, each expression must yield the same result for every value of x. Therefore, it is not enough to simply substitute in values, we must utilize the Rules of Arithmetic to justify the equivalence. If you look at the expressions again, you can see that the second expression can be obtained from the first using the distributive property, and vice versa. Therefore, the two expressions are equivalent.

2 (x+4) = 2 (x)+ 2 (4) =2x+8

Here is another example,

2x+6+20x-10 = 2x+6-10+20x

Using the Commutative Rule of Addition, the terms 20x and -10 have changed positions, but the expressions are still equal.

Solution or Not

A key practice in algebra is the process of checking your answer to determine if it is in fact a solution or not. It is a practice often overlooked by students and instructors alike as it is tedious and may seem redundant. However, it is very important that students understand the process so that they are always able to check their work. This aligns well with Mathematical Practice 6 in the Common Core Standards “attend to precision”.3

The process of checking an answer to an equation is simple. If the answer you determined is correct, you can plug that number into the equation in the place of the variable and the equation should be true.

2x+10=20

2x=10

x=5

I can check this solution, by plugging 5 in to the original equation in the place of x. If both sides of the equation remain true, my solution is correct.

2(5)+10=20

10+10=20

20=20

Since my equation is still true because twenty does equal twenty, I know I have found a solution.

It will also be important that students are able to determine what is a reasonable answer. I will use the above equation to demonstrate. In the equation we are taking a number x and multiplying it by a factor of two and adding ten, the result of this addition is twenty. Students should have a basic understanding then that the variable, x, is not going to be smaller than one. If it were a number less than one then the product of two and the variable would not be nearly large enough to combine with ten to get twenty. Conversely, students should be able to determine that an answer like 100 is also unreasonable as it is much too large. Students should be able to use clues from the equation and the context to mentally check that their answer is reasonable.

Properties of Equality

While this should be review for my students, it is worth the instructional time to make sure that students’ understanding of the concept is strong because it is the foundation of algebraic reasoning. For example consider the following equation:

x-2=10

This equation is unchanged (read: the two sides of the equation are still equal) if the same number is added to both sides of the equation. Since subtraction is just addition of the additive inverse, or negative, the same rules apply for subtraction. We’ll call this “Equals added to equals make equals”.4 Thus, if we add 10 to both sides, we may conclude that

x-2+10=10+10

x+8=20

This same property of equality exists for multiplication and division. Thus, again start with the equation:

x-2=10

The fact that these two expressions are equal will not be changed if both sides of the equation are multiplied by the same number. Again, this is true for division as well since division is multiplication by the multiplicative inverse, or reciprocal. We’ll call this principle “Equals multiplied by equals make equals”.5

3(x+2)=3(10)

These properties are essential knowledge for my students. A firm understanding of these principles will allow them to manipulate any equation to either solve or make it easier to solve. It will also eliminate many common mistakes students make when solving equations.

Inverse Operations

In addition to the properties of equality, a strong understanding of inverse operations and the equivalence of subtraction with adding the additive inverse, and division with multiplying the multiplicative inverse, will be key to ensuring continued success with algebra. In order to understand inverse operations, students must first grasp the concept of the identity element for addition, and the identity element for multiplication. When using the inverse operation the purpose is to transform the term into its identity value so as to remove its impact on the equation. The key Rules of Arithmetic that relate to this situation are the Identity Rules:

a+0=a

ax1=a

These equations demonstrate the basic facts that the sum of any number a and zero is a, the variable is unchanged. To refer to this, we call 0 the additive identity. Similarly, the product of a and 1 is a, the variable is also unchanged. Thus, we call 1 the multiplicative identity. This is important, because if we can transform terms into either their additive or multiplicative identities then we can essentially remove or eliminate them from the equation because they will have no impact on the result. To do this with addition, we use the additive inverse or negative of an element. To do it for multiplication, we use multiplicative inverse, or reciprocal.

x+(-x)=0

7x*1/7x=1

The following are the Rules of Arithmetic governing inverses. The additive inverse of a number, when added to that number, will result in 0, or the additive identity

a + -a = 0.

Likewise, the product of a number and its multiplicative inverse will be 1.

a × 1/a=1.

Employing the additive or multiplicative inverse is often referred to as “doing the opposite”.

Order of Operations

This is essential knowledge to prevent common algebraic mistakes that will change the value of the result. PEMDAS standing for Parentheses, Exponents, Multiplication, Division, Addition, Subtraction is a frequently used acronym to introduce students to order of operations. This, however, can mislead students into believing multiplication supersedes division when in reality they should be considered at the same time from left to right. The same is true of addition and subtraction. A more appropriate acronym is GEMS (Grouping Symbols, Exponents, Multiplication and Division, Subtraction and Addition) because it emphasizes that multiplication and division should be considered at the same time, as should subtraction and addition.

Infinitely Many Solutions, No Solutions

Students will also need to understand when they have found one solution to an equation, no solutions or infinitely many solutions (8.EE.C.7.A). Situations in which the equation has one solution should be relatively obvious to students as this the result that they are typically used to seeing (all of the aforementioned examples have one solution). Students will naturally be less familiar with equations that will result in no solutions or an infinite number of solutions. I will utilize the Hands on Equation model (described in full below) to demonstrate instances of infinitely many or no solutions to give them a physical representation of each scenario.

Essential Strategies

The following represent the strategies that will be essential to my students’ success with equations. Each strategy will be discussed as a class, included in students’ interactive notebooks and also coupled with a visual representation using manipulatives from the Hands on Equations collection. Additionally, there will be an extensive use of word problems to not only give students an understanding of how to translate words into algebraic expressions and equations but to also give them an opportunity to continue practicing these essential skills.

Distributive Property

Students will need to be able to use the distributive property to simplify more complex equations.

3(x+2)=30

The expression x+2 can not be simplified because x and 2 are not like terms. Therefore to simplify the above equation, another method must be employed, the distributive property. Many students will have this method memorized (“the double rainbow, right?” students ask), but I am more interested in them truly understanding why it works. This can be demonstrated with a relatively simple example proof.

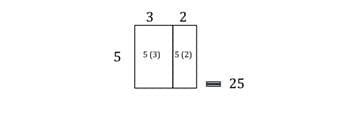

5(3+2)

Since this expression does not have a variable it can be easily simplified and evaluated without the Distributive Rule. We will use that knowledge to check our work with the proof. Students know that multiplication is simply repeated addition so there are then five groups of the sum of three and two.

5(3+2)= (3+2)+ (3+2)+ (3+2)+ (3+2)+ (3+2)

=25

Using the associative property and commutative property of addition many, many times, the numbers can be arranged with the twos preceding the threes.

5(3+2)= 3+3+3+3+3+2+2+2+2+2

=25

From the above students should now be able to see that two is added five times, and three is added five times. Therefore:

5(3+2)= (5x3) + (5x2)

=25

There is also the geometric representation to consider demonstrating for students, in which the values become side lengths and the product is the area. The shape shown below is a composite of two rectangles. There are two ways to find the area of this shape, breaking it into two smaller rectangles and adding the areas, or adding the side lengths together and finding the area of the larger shape. This mirrors the process of the distributive method above, and offers further proof as to why this method can be used.

5(3)+5(2) = 5(3+2)

In this model, the idea that five will be multiplied to both 3 and 2 and that the resulting products will be added together is clearly illustrated, this should be convincing for middle school math students, who have quite a bit of experience with the area of quadrilaterals. This model will also be useful as students move further in algebra and begin to multiply binomials and polynomials.

Sample Problem: Amanda wanted to bring some cookies to a party. She and her son purchased a package of ten cookies and then made c additional cookies from scratch. Becca made twice as many cookies as Amanda and her son brought to the party. Represent the number of cookies Becca made as an expression in terms of c.

Explanation: If Amanda had purchased 10 cookies and then made c amount of cookies we can represent the total amount of cookies she has as c + 10. Since Becca had double this amount multiply the original expression by 2, 2(c +10). Using the distributive, the expression is then expanded to 2c + 20.

2 (c+10) =

2 (c) + 2 (10) =

2c+20

Combining Like Terms

Many students will have experience with this essential skill, but are often lacking a deep understanding of why it is mathematically possible. It is imperative to the simplification of more complicated equations and will be a major underlying component of much of the 8th grade content. Building of students’ knowledge of the distributive property can aide their understanding of like terms and why then can be added together. In fact, combining like terms is simply an application of the distributive property.

Like terms are monomials that contain the same variables raised to the same power. They can be combined to form a single term. Take the following as an example.

5x+3x

Using the distributive property we can rewrite this expression.

5x+3x=x(5+3)

5x+3x=x(8)

5x+3x=8x

It’s worth noting that the above example also utilizes the commutative rule that states that a x b = b x a, or in the above example x (8) is equal to 8x. The factors being multiplied have not changed, their order has simply been reversed.

In this way students can see why we can combine terms that are like, and why you can not combine terms that are not.

5x+3x^2=x(5+3x)

The two terms in the above expression have x as a common factor. When x is removed however, and are not like terms and 5 + 3x cannot be simplified further.

Sample Problem: Hilary made c cookies on Tuesday. She doubled the original recipe on Wednesday. On Thursday, she tripled the original recipe. Write a completely simplified expression representing the number of cookies Hilary baked in terms of c.

Explanation: The amount of cookies Hilary made is represented by c. Double that amount would be 2c and triple that amount would be 3c. To determine the total amount of cookies we add the original amount c, to double and triple that amount (c + 2c + 3c). Using the distributive we can combine like terms.

c+2c+3c = c(1+2+3)

=c(6)

=6c

Clear Equations of Fractions

Rational coefficients, and fractions in general, sincerely frighten the middle school math student. “I hate fractions…I don’t do fractions” is a common thread in my classroom. Having a coefficient that is a fraction can complicate the manipulating of an equation but we can tap into students’ previous knowledge of the properties of equalities to make this process easier for ourselves.

1/5(x+2)=10

Many a student will see this problem on the homework and not attempt it, recalling former difficulties with fractions. But if we recall the multiplicative property of equality, we know that we can multiply both sides of the equation by the same number and maintain the equality of the two expressions. If we multiply both sides of the equation by 5, we get

5[1/5 (x+2)] = 5 (10)

or equivalently, since

5[1/5 (x+2)] = 5(1/5) (x + 2) = 1 (x + 2) = x+2

x+2 = 50

This problem is now more easily solved. Admittedly this is a very simple example of equations with rational coefficients, but with a firm understanding of the properties of equality and the possibilities for manipulating equations, students will be able to use those properties to simplify the process for themselves.

Sample Problem: Pat had p pounds of cookie dough in her freezer. At the grocery store she purchased 3 additional pounds. Her daughter asked for 1/4th of the total cookie dough Pat had in her fridge. If Pat gave her daughter 3 pounds of cookie dough, how much did she have originally?

Explanation: If Pat originally had p pounds, then 3 more pounds would be p + 3 pounds, so 1/4th of that would be (1/4) (p +3). Since that total is 3 pounds the result is the following equation

1/4(p+3)=3

4[1/4(p+3)] = 4(3)

p+4=12

p=9

Using Properties of Equality to Solve Equations

Ultimately, the goal is for students to put all of this together and utilize the strategies to solve one- , two- and multi-step equations. At this stage, the use of word problems will also be integrated more heavily into the process. Students will have had experience in previous lessons translating words to algebraic expressions and they will continue that process here with complete equations.

In order to pull together all the above-mentioned essential knowledge and strategies for students to be successful with equations, I will employ a hands on approach to understanding equations conveniently known as “Hands on Equations”. This is discussed further in the Teaching Strategies section below.

Sample Problems

Can be set up with visual model

Monica made some cookies and then bought a package of 12 cookies. Monica’s sister made double the amount that Monica made herself. Together they now have 36 cookies, how many did Monica make to begin with?

Less suitable to visual model

Monica had some cookies. She gave half to her sister and then ate five, and still had four left over. How many cookies did she have originally?

Comments: