Teaching Strategies

When setting out to accomplish a unit of learning with two purposes – to enlighten teens about and reinforce their real and present impact on the world around them, and to encourage them to view reading as an important aspect of their and all our lives – one may wonder which goal to start with. Teens can be naturally rebellious, and these concepts can be alien to them. They have been in school a number of years and may still not appreciate reading. They have been humans for even longer and may still not appreciate what that means to the other humans around them. Reading is part of coming to the realization that we “are on the world, not in it,” as John Muir said, that we share this world with our fellow humans. We read for joy and we read to realize this. We read for escape and we read to reconcile ourselves to mortality. We read to gain knowledge and also to discover truth. But the first two reasons – to discover that we have a place in the world and it is our job to find it, and for sheer enjoyment – are what we will focus on here.

There is a point in every reader’s life that he or she can recall as motivation to become a real reader – one who reads for both that joy and self-growth. For me, an English teacher, that point was not until I was in college. I read the first Harry Potter book when I was 19, and the 6 subsequent books quickly thereafter. This reading roiled that “stir” – it created in me a drive and motivation and fire to devour more written words. That is my hope for students in their junior and senior years of high school. If they have not been bitten, as it were, by any books yet – not yet affected by any pages that have made them crave more – I want them to have had that experience by this point. I want them to realize that books can be both engaging and highly intellectual; they can be simple but not simplistic and accessible while also being culturally relevant.

In my six years as a teacher, I have always found that culturally relevant literature has been effective in engaging students of color. I have also found that non-culturally relevant literature has been effective in engaging the same students. All forms of literature can be engaging to all forms of people. Therefore it is my goal with this curricular unit to enlighten students and educators alike that there needs to be a good cultural mix in literature studies, for all students, everywhere. In my inner-city required curricula, the recommended books are mostly Western Canon, which is of course immeasurably rich in lesson and theme and even potential for enjoyment. But that is not all there is for students of any race to read and learn from and grow and enjoy. It is important, especially for young people who are not very interested in reading, to lure them in with material that is relevant to them. According to Mary-Virginia Feger of the School of Education at University of South Florida, student engagement is not only improved by culturally relevant reading, but can actually encourage students to want to read. This can work with both fiction and non-fiction, and does so because it supports their identities.4 And I believe this is a powerful place to begin. If we want students to discover how to expand their identities and incorporate them into society, what better a place to start than with themselves, with literature through which they can view similar experiences to their own or people who mirror their own voices? Starting this way will of course look different at different schools and with differing student demographics – for those that differ, this unit could be supplemental as opposed to introductory.

Introducing African-American Literature

We will begin with visual art as a hook. Not only might students be pleasantly surprised to begin a unit about reading with pictures (the paintings of Jacob Lawrence), but fine art can be a phenomenal tool for focus on the study of words – a picture is worth a thousand of them, after all. We will then subtly transition into the textual version of art – poetry. Langston Hughes will open a doorway from visual to verbal art with his flowing and wonderfully readable verse. From there, we will take our first look at prose with excerpts from the compelling Harlem Renaissance novel Passing (1929) by Nella Larsen.

From the Harlem Renaissance we will transition to literature of the fiery Civil Rights Movement of the sixties. The charged memoir The Fire Next Time (1963) by James Baldwin will open a door for students to connect through apprehension and anxiety and even anger – all emotions with which teenagers are familiar. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s poignant essay “Letter from Birmingham Jail” (1963) will connect this anger and expression with purpose, drive, and the yearning for liberty. It is integral when encouraging students to read for joy and self-actualization to include some work that will take them out of their comfort zones, even prompt confusion or anger or a feeling of injustice.

We will then culminate with novel-length memoir study. Up to this point, students will not have read a text more than 25 pages long – they will “warm-up” to reading a text of this length, as it were. The Color of Water by James McBride is a marvelously multi-faceted study of identity – a journey to find oneself, one’s origin, one’s place in the word, the strength to do it well, and to be kind along the way. It is challenging in its language at times, but narratively accessible and fascinating, and it rivets students.

The Harlem Renaissance

I have experimented. The Great Northern African-American migration is fascinating to students of all races. Harlem Renaissance poetry appeals to more high school students than does Romantic poetry (sweeping generalization notwithstanding), especially that of the accessible and poignant Langston Hughes. Students in general are enthralled by the story of the first significant arts movement of Black America. The story of the post-Civil War American South, which I tell them, is an effective and important introduction to the study of the Harlem Renaissance.

A Very Brief Survey of the Great Migration and Harlem Renaissance

After the Civil War, the American South, to put it subtly, did not welcome the freed slaves with open arms. Many indignant former slave owners were not overly willing to employ labor they previously had through subjugation and bondage at no cost beyond the buying price of the individual slave, so jobs for freed blacks were few. To worsen matters, the South was suffering a crop famine that made work even harder to find for laborers whose skills were mostly agrarian. An ambitious few began traveling north, followed by more and more upon receiving word from their friends or relatives that northern cities – mainly Chicago, St. Louis, and New York – were epicenters of opportunity for unskilled labor in a booming market of industry and factories. More and more people began moving northward, on foot in many cases, to the point that hundreds of thousands migrated from the South to these cities. The movement came to be known as the Great Northern Migration, and it became the salvation for many African-American families who continued to suffer in the South after the Civil War. A generation later, these factory laborers’ children went to school, though many of their parents had not. In New York, many of these newly educated and enlightened African-Americans began making art in Harlem – painters, poets, actors and dancers, writers. The movement, which took place in the 1920’s and 30’s, became known as the Harlem Renaissance.

There were many historic artists born from this movement – including Countee Cullen, Jean Toomer, Zora Neale Hurston, Josephine Baker, and Claude McKay. This unit will focus on three in particular for their flash, style and – mostly – accessibility. The art of Jacob Lawrence captures the Great Northern Migration and life and art of the era in Harlem. The poetry of Langston Hughes is seminally American, and it is rich for analysis. Helpfully, it initially seems to have clear meaning so is not off-putting for students, but the more time they spend the more it repays sustained and deep analysis. Nella Larsen wrote a lesser known, but haunting and compelling novel in Passing, for which we will use an excerpt. These qualities make these artists particularly apt for introduction to this study.

Jacob Lawrence

Jacob Lawrence, a child himself of American northward migrants, was born in Atlantic City, New Jersey in 1917. In 1930 he moved to New York and received some formal training while being inspired by the life he observed, and he began to interact with other artists of the Harlem Renaissance. He became known for his depictions of contemporary African-American urban life, as well as historical events like the Great Migration. He would also go on to become an art teacher.5

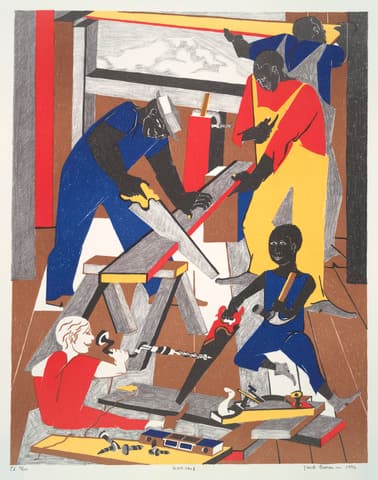

The paintings of Jacob Lawrence are vivid in color and dramatic in scope. They depict both struggle and triumph, power and vulnerability – and overall create a foundation for study of the time period. These images are very useful to introduce poetry as they can inspire poetic thinking. For example:

”Workshop” (1972), color lithograph, source: Yale University Art Gallery

This depiction of African-Americans working in Harlem, entitled “Workshop,” 6 gives a positive view of the energy in the city, and the spirit of the people. The vibrant colors, indeed, represent the vibrancy of the culture, even in work. Students may notice the black and white children working together as a symbol of the synergy of the races that was also a part of the Harlem Renaissance (small as it was, it was a positive step). Taking a look at such paintings can be a good way for students to get into the artistic, appreciative mentality good for the introduction of poetry, which we will take a look at next in the work of Langston Hughes. Activities involving Jacob Lawrence’s art can be found in the “Classroom Activities” section of this unit.

Langston Hughes

Poetry as a warm-up to the study and appreciation of prose can be an effective strategy – poems are (or can be) short. The poetry of Langston Hughes is advantageous in its accessibility. If you’ve ever watched the face of a child brighten as she becomes impressed with herself after understanding a poem, then you realize, or can imagine, its power. Students “get” Langston Hughes – they follow his words in “I, Too, Sing America” and “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.” I have taught poetry for years, including many poems from the Harlem Renaissance. All of it is “interesting” to students – it is nicer and of course more lyrical than many texts, however I have found over and over that Langston Hughes is among the most accessible of any literature to students. It is the most powerful and hard-hitting, while at the same time accessible to students of any background. They engage in his words – more simple in their style but just as deep, intense, and often dark as any literature of its or any other time or movement.

“I, Too, Sing America” is a powerful poem and is widely available on the internet (see “Teacher Resources”). With the appropriate historical context of a person being banished to the kitchen, the action of this poem is fairly straightforward, it is enjoyable, and it prompts students to think about power, identity, freedom, racism and tolerance. This is wonderful for class discussion, journal responses, and empowering students with an opportunity to easily “get” poetry.

An even more complex poem requiring deeper exploration and analysis but can still appeal to students is “Harlem.” It is about dreams, aspirations, goals. This is particularly apt to consider when juniors or seniors are writing college essays. What does Hughes mean when he utters the haunting final line begging the question as to whether deferred dreams explode? In some ways, jolting students’ sensibilities can be effective. Helping them to the realization that we can figuratively explode if our dreams go unfulfilled can motivate them to focus on and realize what their dreams are. Once that is at least tentatively achieved, that is a guide to college search and college essay writing.

Nella Larsen and the Harlem Renaissance Novel

Not enough focus in public school literature is on African-Americans. Yet there is another demographic that is overlooked in how much it is overlooked: women. Larsen was not only an artist of the Harlem Renaissance with a powerful woman’s voice, she was also a highly compelling writer. She wrote two novels – Quicksand (1928) and Passing – that earned her fame for a brief time before she gave up writing and faded into obscurity as a nurse in New York City. Her second novel, Passing, which will be a focus in this curricular unit, mirrored her own experience and insecurities as the only black child in a white family. Her mother who was white, after divorcing her father who was black, remarried a white man, and they produced her half-sister.7 The novel, is about two old friends – Irene Redfield, a prominent black woman of Harlem, and Clare Kendry, a black woman Irene has not seen in years. Upon meeting Clare by happenstance on a trip to Chicago, Irene discovers that Clare has been “passing” as white.

This novel is rich for this unit because first and foremost it is engaging. The story of a black woman of the 1920’s passing as white, and her friend whose own take on her true self is affected by their new, not wholly welcome relationship, is something that can help students contemplate what it means to be in their own skin. This passage from the novel depicts the curious perplexity that Irene experiences upon learning what her friend has been up to:

The truth was, [Irene] was curious. There were things that she wanted to ask Clare Kendry. She wished to find out about this hazardous business of “passing,” this breaking away from all that was familiar and friendly to take one’s chance in another environment, not entirely strange, perhaps, but certainly not entirely friendly. . . .As if aware of her desire and her hesitation, Clare remarked thoughtfully: “You know, ‘Rene, I’ve often wondered why more colored girls, girls like you. . .never ‘passed’ over. It’s such a frightfully easy thing to do.’8

Immediately students wonder: Why is this such an easy thing to do? Why do it at all? Students can be compelled to consider the context and the “times” – what America was like for African-Americans in the 1920’s and, just as importantly, this raises the question: is it any better now?

Larsen’s novel seethes with racial and sexual and marital tensions. It is a profound study of identity – learning oneself through who we (whether or not through any effort of our own) interact with: friends, acquaintances, enemies. Clare goes on to infiltrate Irene’s life – moving in on her group of friends, even having an affair with her husband. Clare is the clear villain, if we needed to identify one, in the story. Yet Clare’s character is also very sympathetic. When we ask the question, “why would she choose or feel she needed to ‘pass,’” we discover a black woman who is so uncomfortable in her own skin – for reasons either intrinsic, extrinsic or most likely both – that she is compelled to make the effort to completely convert to another race, the dominant race. A good word to study in this context is minority – taking a look at what it really means. What different things make a minority so, and in what context? Can I be a minority in one environment and not in another? And what is the opposite, considering this usage – a majority? What would that look like?

Another word to consider is that in the title: Passing. In this case, the obvious meaning is the one that is outlined in the story – going unnoticed while pretending to be of a different race – assuming another identity. But the word itself can relate in so many other ways to high school juniors or seniors. Completing classes and assignments with passing grades (at minimum!) is at the forefront of their thoughts (or should be). Passing from one stage of their life to another in high school graduation and possibly moving on to college is an excitement and an anxiety. Contemplating the different meanings of words is an important part of what literature can help us do in a meaningful way.

Finally, I will be using a 25-page excerpt of the much longer novel for these purposes. This may make it easier for students to enjoy and appreciate by cutting out some of the drier exposition and denser parts of the text. I will focus more on the advantages and disadvantages of using an excerpt as opposed to a whole text later on in this curricular unit.

The American Civil Rights Movement: A Study in Letters

The American Civil Rights Movement is one of the foremost historical periods in African-American, and indeed American history, and stands then as a basis for the continuation of instruction in the love and learning of literature in this unit. It is a strategy in and of itself to explore non-fiction as a type of literature (after-all, it’s what most of the standards these days are calling for, and its inclusion may legitimize this unit to supervisors), giving students a chance to react to factual information, extract pertinent points (read for information), contemplate, discuss, debate and write about the compelling, poignant nature of the featured pieces, and learn that even non-fiction can be accessible as well as important. For these purposes, we will be taking a look at “My Dungeon Shook: Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation,” a letter introducing James Baldwin’s fiery memoir The Fire Next Time, and the seminal “Letter from Birmingham Jail” by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Both pieces of non-fiction are incendiary, spectacularly compelling, quick-reading, rich in both interest and dynamic of rhetoric (rife with potential for stylistic and grammatical instruction), and relevant to not only American history, but many things regarding race relations today.

Dr. King’s Letter

The impact on the course of this country’s history by the letter Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote from his jail cell in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963 is immeasurable. It is summed up, however, by Mark Gaipa in his essay on the subject, “’A Creative Psalm of Brotherhood’: The (De)Constructive Play in Martin Luther King’s ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’”: “Without the document and events in Alabama, the March on

Washington would not have been possible.”9 Gaipa goes on to quote S. Jonathan Bass in this same article, who went so far as to say the letter is “the most important written document of the civil rights era.”10 It is hard to understate the importance of the letter, and when using it to help intensify that “stir” in students when they read, we can simultaneously understand why. The letter is full of fiery tone and poignant rhetoric. One can feel the desperate aggravation and finality of the choice to act against an unjust society:

One may well ask: "How can you advocate breaking some laws and obeying others?" The answer lies in the fact that there are two types of laws: just and unjust. I would be the first to advocate obeying just laws. One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.11

Moreover, the letter is consistently eloquent; Dr. King poised throughout. It is what Gaipa calls “from start to finish, a piece of writing.”12 The letter is something that can be close read for how to write (this will be explored further in the “Classroom Activities” section below). It is a piece that may awaken a love of reading, especially when read at the right time in a student’s life, or even after close reading. If an educator can inspire attention with or through this piece in students who do not “like” to read or are often too distracted to engage, this could be the work that “snaps” them out of it, much as the Harry Potter series was for me all those years ago in college (not an apt comparison to Dr. King, simply another example).

This is a foremost example of accessible meets great. Dr. King is never so controversial that a modern student may take offense, his eloquence and reason don’t allow for it. Additionally, this letter does not slow down. There is little exposition. There aren’t mundane details a student must endure. Each paragraph is charged and meaningful, with beautiful, undeniable language that could perk up even the most cortisol-entrenched teen. That is why we begin this section of the unit with it, and then move on to James Baldwin, which is more intense, but in a good way – a way that can draw on teens’ sense of rebellion and, like Dr. King’s letter, offer them through reading and thinking a healthy way to express themselves.

Baldwin’s Letter

James Baldwin begins his incendiary Civil Rights memoir The Fire Next Time with another letter, one written to his nephew. Published in 1963, the same year as Dr. King’s letter, “My Dungeon Shook: Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation” is a powerful way to inspire teens to read. While specifically written to his nephew about the power of being black and the importance of not allowing oneself to be oppressed, it also reads like an open letter to anyone who feels like an underdog. And many teenagers, at least at times, feel held down by someone – if not society, then their parents, teachers, and even friends. Baldwin speaks to them in his opening lines: “[Y]ou are tough. . . .vulnerable, moody – with a very definite tendency to sound truculent because you want no one to think you are soft.”13 The tone speaks to the anxious, perhaps even rebellious teenager who does not want anyone to have an ill opinion of him or her. Again, although this letter is addressed to an African-American boy, it can be read with fascination by teenagers of any race or sex.

This letter exceeds Dr. King’s in its potential to create a sense of offense in its reader. It is less diplomatic, more direct. Baldwin freely and necessarily draws lines between “black” and “white” and the victim and culprit of grave treatment:

You were born where you were born and faced the future that you faced because you were black and for no other reason. The limits of your ambition were, thus, expected to be set forever. You were born into a society which spelled out with brutal clarity, and in as many ways as possible, that you were a worthless human being. You were not expected to aspire to excellence: you were expected to make peace with mediocrity.14

While Baldwin often refers to whites to his nephew as “your countrymen,” the necessarily divisive tone is there. However this does not mean that Dr. King’s is less powerful or provocative. It is quite so using rhetoric and tone whereas Baldwin uses direct language (an important distinction when comparing the two pieces). In fact, Dr. King begins his letter by talking about tension; and now while teaching Mr. Baldwin’s letter, it is a good time to refer back to that: “But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word ‘tension.’ I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth.”15

What other issues persist today that would be well-introduced in this way – with a conversation about “constructive tension”? I was recently at a professional development workshop where the moderators opened with an exercise, asking all to link their fingers together as they usually do when the occasion, for whatever reason, calls for their hands to be clasped. They then instructed us to re-link our fingers with the opposite finger making the top of the hand-clasp, and to sit with that for a minute and notice the difference. Sounds of discomfort emanated from the group, and folks started discussing that it was uncomfortable, didn’t feel quite right. Sometimes when people talk with each other about serious issues, especially issues revolving around our differences, it can feel this way, but it is just as, if not more, necessary. Close reading of this letter can enlighten students to their own feelings and experiences surrounding these issues, including those of the national and local climates of racism, the necessary tension or discomfort involved in growth and change (going outside their comfort zones), and family issues, highlighted further in the “Classroom Activities” section below.

James Baldwin and Dr. King knew that openness and candor and action were necessary for growth and change. That’s why they wrote these letters. That’s why this literature is still so relevant today, why it is an apt introduction to our novel-length memoir study about a black man who was raised by a white mother.

Modern African-American Literature: The Color of Water by James McBride

Hopefully by now students are comfortable, maybe even excited about reading more. The poems of Langston Hughes paired with the art of Jacob Lawrence, excerpt of an exciting part of Larsen’s novel, and fiery, powerful prose by two of the foremost voices of the Civil Rights Movement were chosen in this instance specifically to “warm up” the students to take on a more extended, in-depth reading adventure (a word it wouldn’t hurt to use when describing this assignment to them). The capstone of this unit, studying a full-length book, is the most engaging component yet. I cannot call it a novel study, since The Color of Water is not a novel, but it reads like a novel, as it were – one of many reasons to choose it for these purposes. It is the story of a black journalist and musician whose mother was a white, Jewish woman from the South who raised eight children from her first husband, a black Brooklyn minister, and four more children from her second husband, also a black man, after becoming twice-widowed. She raised them all while poor in New York City and, spoiler alert, they all went to college and became professionals, from teachers to doctors. The story is consistently interesting, weaving the past of McBride, the author, with a first-hand confessional from his mother Rachel about her own past. It takes us from poor Black New York, to poor Jewish Virginia, and everywhere both mother and son visited in between in their often tumultuous lives, at times interweaving their stories and ultimately redeeming for their family. I have read this book with and to students before, and the feedback is always the same: it is a great, interesting story, with a lot to take away and learn from. H. Jack Geiger, a doctor and journalist who has had experiences with civil rights and interacted with Langston Hughes in his lifetime, offers a synopsis of the book in The New York Times. He explains that “only as an adult did James McBride convince his mother. . . .to tell the story of. . . .her past. And it is her voice – unique, incisive, at once unsparing and ironic – that is dominant in this paired history, and its richest contribution.”16 The stories of James, which includes forays into a life of crime, and Rachel, who at one point nearly became a prostitute in Harlem (by circumstance and naiveté, it is made clear that she never would have come as close had she known her path was leading to it) are so compelling, and so well-written that the only complaint I’ve ever had from students was when reading time was over. Yes, I’ve read this aloud to high school seniors to amazing results. I have also taught other books using audiobooks recorded with captivating narrators. The advantages of this method are explored further in the below section “Sneaking in through the Window.”

Both son and mother, in their upbringings, dealt with racism and prejudice as well as poverty, but also intra-family strife. Both had issues with siblings although Rachel had much more significant issues with abusive parents. This can upon analysis be connected with the previous discussion about family in Baldwin’s letter. Reading the book is valuable in its connections to all previously read materials within this curricular unit, and ultimately products inspired by its reading can show how learning emerges from not just the book, but also said excerpts, poems, artwork, and letters. These products are outlined in the below “Classroom Activities” section.

Reading is Good, Too: Convincing Young People Also to Choose Books

Students do not have to be convinced to use Snapchat or Twitter or Facebook or Instagram, yet they seem to need to be practically bribed to actually read. For all your efforts, if you have followed this curricular unit to the word, used every available resource, even trod your own path and chosen works that you have researched or found to be compelling, engaging, accessible examples of great literature, your students still may reject reading as if it were a wayward mobile app. They may still need some convincing. For the technocrats in your classroom, students that need convincing by empirical evidence that reading is necessary and valuable for growth, that it will directly benefit them. There is actually scientific theory and evidence that shows this is the case.

It is easier to explain to students why science (curing disease), math (analytical reasoning), or history (vying to not repeat mistakes of the past) are more necessary school subjects for growth and learning than reading literature. It would seem that it is less scientific, but research has been done to show that there is a science to why we read. In her book Why Literature? The Value of Literary Reading and What it Means for Teaching, Cristina Vischer Bruns explores the instructive quality of reading, and its advantage as a source of pleasure. She notes the experiential value we receive from literature through shock, recognition, even enchantment.17 But most importantly for our purposes here, she proposes that literature has a transitional quality – an aspect of the written word through which we can explore ourselves. She describes through her own and others’ research, that there is a place we can find through reading between ourselves and the world. A “transitional space” that is made up of both our inner-selves, and the world around us. This is a space where one can explore their relation to the world.18 In this way, reading is imperative practice in accepting, dealing with, and finding a balance and comfort with the reality of our world. Life can be tough, as we and many of our students know, and reading is, not “can be,” but is, a tool in navigating the tumultuous waters of life and the world. Finding that “transitional” space in books is, according to Bruns and others, an imperative practice in being able to relate to others, to issues and problems. In this way, reading is a subject most-comparable, of the subjects listed above, to math’s analytical reasoning. We can, scientifically speaking, develop better coping skills, people skills, and even reasoning and problem-solving skills, by reading books. Discussion of the transitional quality of reading is helpful in executing this unit, and it can perhaps silence (or at least slow) the analytic doubters in your classroom.

Sneaking in through the Window: Using Excerpts and Audiobooks to Spark the “Stir”

When I embarked on one of my own life’s most significant journeys – the journey to become a teacher – I left the world of marketing and began looking into training. As my undergraduate degree was not in education, I needed the right program to gain certification. I found a Master’s program near my home in New Haven, but in my search I found other ways – what were called “alternate routes to certification.” Students can always simply read, or take the “standard route,” as it were – and if that works, wonderful! However, for those who may need what I’ll call the “alternate route to reading,” there are ways to engage them other than reading the material eye-to-page or in its entirety.

Excerpts can be powerful. As is utilized in the Nella Larsen section of this unit, if students are offered a brief and more compelling section of a book or essay or even article, they may be more willing to read it without being daunted or overwhelmed. We offer famous quotations as lesson warm-ups for journal responses, we close read paragraphs or sentences. We can also offer excerpts from paragraphs to several pages of books if we find, as I have in this case, that it may be valuable in sparking the interest of students to read.

Audiobooks too can be an alternate route to reading. As I mentioned earlier, I have myself read aloud The Color of Water in its entirety to students. I have also assigned other books to be “read” during class – usually shorter novels like Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, for two reasons. First, it is a way to ensure that students actually read the text. If you have or can make the class time to do it, it can help a teacher immensely, in related lessons and activities, to know all of the students in the room have read the text. Secondly, audiobooks are now more available and ubiquitous than ever with the advent of audible.com (more on that in “Teacher Resources”). Often, books are read by captivating and even famous narrators. The audio version of the aforementioned Fahrenheit 451 is read by Tim Robbins, and it is fantastic. There is a version of “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” read by Langston Hughes himself available on Youtube (with a bit of exposition by the author, see “Teacher Resources”). The two famous Civil Rights era letters featured in this curricular unit have fantastic audio versions, James Baldwin’s being read by Jesse L. Martin, an actor of note, and Dr. King’s being read by a narrator who performs it as a fiery oration. Another advantage of reading with audiobooks (as opposed to reading to students yourself) is that you can check that each student is reading while the audiobook is playing.

Through these alternate routes to reading, it is possible to catch that one extra learner, or two or three or ten, who may not be reading otherwise.

Application of these Skills and Topics to Writing of College Essays

Focusing on identity and life’s growth and journey, students can not only develop a love of literature and be encouraged to find a place in the world, but in their junior or senior years of high school find an immediate application – their college essay. Any teacher who has helped guide, revise, or inspire the conception of a student’s college essay knows that common problems when starting out are: “But I just hate writing about myself” and “I can’t think of anything to write!” Reading the stories of others’ personal journeys may unleash students’ ideas; connecting with themselves through the text may open the right mental or emotion door through which to craft a wonderful, representative college essay or personal statement.

Comments: