Content Background

Criminal justice in both theory and practice has changed significantly in the United States since its inception. Before the American Revolution, prisons as we know them today did not exist. Common punishments for crimes or civil disobedience included public whippings, lockup in the stocks or pillory, bodily mutilations and executions. Much of the early punishments for criminals had roots in religious ideology; given that religion permeated every aspect of colonial life, it should come as no surprise that the methods of punishing criminal acts had secular foundations. Most punishments were public and intended to shame the recipient; the use of harsh public punishments also served as a deterrent to would-be criminals.2

Colonial America and the First Penitentiary

Philadelphia became a leader in prison reform in the late-18th century. The High Street Jail was constructed in the late-17th century primarily as a holding facility as criminals awaited trial or sentencing. Rampant corruption and overcrowding plagued the facilities in Philadelphia, foreshadowing the conditions at large centuries later.

In 1776, the Walnut Street Jail opened, replacing the High Street Jail. The first penitentiary was constructed in 1790 and arose from the Quakers’ belief in penitence and self-reflection as a means of rehabilitation and salvation. The roots of solitary confinement can be traced back to the Walnut Street Jail, eventually being practiced at Eastern State Penitentiary in 1829. At the time, the system of separate incarceration was the first of its kind and would pave the way for the modern prison system still in employment today. Eastern State would serve as a model for hundreds of prisons across the world. The Penitentiary is perhaps most significant because it marks a change in the function of prison: imprisonment as a punishment for crime or wrongdoing.3 Again foreshadowing conditions of contemporary facilities, the effectiveness of the penitentiary was ultimately undermined due to overcrowding.4

Nixon and the Emergence of the “Tough on Crime” Movement

Coincidentally, as the Eastern State Penitentiary was closing in the early 1970s, a myriad of other factors were coalescing to create the foundations of mass incarceration that now prevail today. Criminal justice under the Nixon administration took on a new identity as the tough-on-crime mentality pervaded American politics. Crime became a national issue as the murder rate doubled from the 1960-1975. During this time the robbery rate more than tripled. Furthermore, the rhetorical war on drugs exponentially increased the size of federal drug agencies and laid the groundwork for some of the major issues still plaguing the criminal justice system today. As crime rates continued to rise, “law and order” became a mantra that held serious political capital and would propel its adopters into office. The War on Drugs would pave the way for mass incarceration with the policies and ideologies that invaded American politics.

|

Year |

Population |

Violent Crime Total |

Murder and Non-negligent Manslaughter |

Robbery |

|

1960 |

179,323,175 |

288,460 |

9,110 |

107,840 |

|

1965 |

193,526,000 |

387,390 |

9,960 |

138,690 |

|

1970 |

202,235,298 |

738,820 |

16,000 |

349,860 |

|

1975 |

213,124,000 |

1,039,710 |

20,510 |

470,500 |

As the number of violent crimes rose through the late-1960s and 1970s, politicians recognized the political capital to be gained from adopting “tough-on-crime” stances.

Source: Uniform Crime Reporting Statistics, Federal Bureau of Investigation.

During the 1960s, as the civil rights and antiwar movements gained traction, participants gained an involved understanding of the prison system. Many were arrested as a result of their activism, awarding them firsthand knowledge of the carceral experience for periods of days, months or years. There was partisan divide over the perception of crime and punishment. “Growing numbers of sociologists and people on the left also came to see crime as essentially learned behavior that was a rational, if illegal, response to a set of social conditions.”5 Particular focus fell on the system of indeterminate sentencing. The most powerful incentive intentioned within the system of indeterminate sentencing was a premature release. Judges could exercise discretion in assigning a minimum and maximum prison term for each infraction, with parole boards exercising discretion in granting release dates.6 Indiscriminate sentencing encouraged rehabilitation; in theory, prisoners would be motivated to employ good behavior during their term and complete programs to earn an early release, proving they were ready to reintegrate to society.

The left challenged the indeterminate sentencing for its propensity to the arbitrary use of authority in race and class-based ways. In particular, the case of George Jackson, the “Soledad Brother” proved their point; sentenced to 1-70 years for robbing a gas station, Jackson was eventually shot and killed in prison, but became a martyr for those who saw an excessive indeterminate sentence as ironclad as life without parole. The right, however, were more concerned with rising crime rates in the 1960s and the perceived pro-defendant decisions of the Supreme Court. One example, Mallory v. United States, affirmed the right of defendants to counsel and a preliminary hearing without unnecessary delay. More famously, Miranda v. Arizona firmly established the constitutional basis for “Miranda rights” that expanded Fifth Amendment protections during police interrogations. Many on the right challenged the decisions of the Warren Court as too soft on crime, giving defendants more leeway in criminal proceedings than they believed they ought to have.

In 1948, a public investigation into the Philadelphia police department exposed widespread corruption. In response, voters ratified a Home Rule Charter, attempting to keep political influences away from the police. The Home Rule era saw a rise in aggressive police tactics, with officers targeting low-level drug pushers and users in the poor and predominantly black neighborhoods of South and North Philadelphia. Later, in the 1950s, the Philadelphia Police Department broke new ground in community relations by organizing regular meetings in black neighborhoods to improve relationships with police. Still, the force was more than 95 percent white and a 1957 survey found that most white officers thought African Americans had a natural inclination towards crime. Thirty-two people were shot and killed by police between 1950 and 1960. Twenty-eight, or 87.5%, were black. During this time, African Americans made up 22% of Philadelphia’s population.7 Attitudes among Philadelphia whites, especially police, fit the national standard of racial attitudes.

Conservatives began to mobilize against crime as a central political issue. Barry Goldwater’s presidential campaign in 1964 and Richard Nixon’s successful run in 1968 embodied the platform of “law and order” as a national issue for the first time. The law and order platform was a response to urban restlessness and antiwar protests, however, there were not-so-subtle racial implications for whites who were worried over ostensible rises in black criminal behavior. What would be referred to as dog-whistle politics today galvanized a portion of conservative white America who had serious qualms with the Democratic Party’s support of civil rights and voting rights for African Americans. Conservatives attacked discretionary indeterminate sentencing policies, alleging that convicted criminals should serve the full term of their sentence. Harvard professor and conservative criminal justice scholar James Q. Wilson advocated for isolation and punishment in his popular piece Thinking About Crime.8 The stage was a set for the beginning of the United States’ emergence as a world leader in incarceration.

Halfway through the 1960s, a combination of police brutality and urban rebellions following Martin Luther King’s assassination, among other factors, led to growing urban unrest. The white perspective tended to view these incidents as examples of common criminality, rather than the civil rights and antiwar protests that they truly were. While some considered crime and the burgeoning urban unrest a reaction to an oppressive system, the reality is that many of the victims of crime were of an oppressed class themselves. What was purported simply as a growing culture of urban crime was something entirely different.9

Francis “Frank” Lazarro Rizzo joined the Philadelphia police force in the 1940s. Rizzo served as police commissioner beginning in 1967, and as the 93rd mayor of Philadelphia from 1972-80. Police relations with the black community in Philadelphia were tenuous at best under Rizzo. In 1964, riots on Columbia Avenue in North Philadelphia occurred over the course of 3 days. It was during this time that get-tough policies gained widespread attention in the city. Initially ordered by then-Commissioner Howard Leary to contain the riots with minimal force, the majority-white police force felt neutered during the altercations. As champion of rank-and-file officers, Deputy Commissioner Rizzo battled with Leary over firearm usage. This debate would foreshadow Rizzo’s staunch advocacy of the tough-on-crime attitudes that pervaded national attitudes and politics at the time.10

As Commissioner, Rizzo fit the conservative mold by waging war on a number of groups including the poor, civil rights advocates and antiwar protestors. Hippies, homosexuals and antiwar advocates in particular fell under the boot of the Philadelphia Police Department, led by Rizzo. In one instance, police raided Black Panther headquarters and strip-searched them in front of reporters. Federal lawsuits curtailed the use of some aggressive tactics, such as the use of force against fleeing felons. The biggest year for police shootings under Rizzo was 1974; out of ninety-seven suspects shot, thirty-one were killed by Philadelphia police.11

During Rizzo’s tenure as Commissioner, 20% of Philadelphia Police officers were African American. While significant at the time compared to national averages, the hiring of black officers declined under his watch. Between 1966 and 1970, the percentage of black officers fell from 27.5% to just 7.7%. By 1971, the total percentage of African American officers staffed in Philadelphia was at 18%, compared to the previous 20% 3 years prior. The decline evidenced discriminatory hiring practices in the form of written examinations and background investigations, among other factors.12 The New York Times noted as much in a 1971 article comparing the failures of most major cities to recruit black officers to the force.13

As stated earlier, the left and the right grappled over sentencing policies in the beginning of the “tough on crime” movement. Both wanted determinate sentences, but disagreed on the length. In general, liberals found short, definitive sentences to be more palatable. Conservatives advocated for longer sentences to repay one’s debt to society. Conservatives got their wish with New York’s passage of the Rockefeller Drug Laws in 1973. The precedent was set for a national trend in drug sentencing. Named after New York mayor Nelson Rockefeller, the laws were the harshest in the nation at the time, calling for mandatory prison terms for narcotics offenses. These policies “set the stage in nearly every state for legislation in the following decades for new presumptive sentencing laws for drug crimes.”14 The Rockefeller Drug Laws would serve as a bleak precursor to drug policy, the consequences of which are still being felt today.

The 80s: Reagan, Crack, and the War on Drugs

The rhetorical war on drugs became literal in the 1980s under Ronald Reagan. Reagan’s presidency marked the beginning of massively heightened rates of incarceration, due in large part to the expansion of the War on Drugs. As a result of the policies implemented under the Reagan administration, the amount of nonviolent drug offenders would number over 400,000 by the mid 1990s. The War on Drugs in the 1980s was a response to the emergence of smokeable cocaine in rock form, known as “crack.” Laws passed in 1986 created a 100:1 sentencing disparity for the possession or trafficking of crack-cocaine in comparison to the powder form. Given that crack-cocaine was primarily used by people of color in low-income regions, this created a severe racial disparity in the prison system. The 1980s also saw the rise of the “warrior cop” and the propagation and normalization of aggressive policing and no-knock raids, which are still utilized today, often with dubious efficacy.

Nixon’s administration created the foundations of the “tough on crime” attitudes and the War on Drugs that would envelop the nation under Ronald Reagan, leading to massive upticks in incarceration rates. In 1981, the total number of incarcerated people was approximately 353,167. By the end of Reagan’s presidency, that number had risen to 680,955.

Reagan reinvented the role of government and its relation to social programs. The Reagan administration blamed the issues of crime and addiction on the individual; given that it was a result of poor choices on behalf of those with a poor moral compass, government should not and would not assist with rehabilitating societal problems.

The “get tough” approach was expanded as the government employed a series of remedies that punished offenders, rather than trying to enlist systemic remedies such as preventative programs or rehabilitation for apprehended offenders. Traditionally, most crime is locally based and prosecuted. How, then, would the Reagan administration expand the role of the federal government in crime control? Attorney General William French Smith found the answer: a federal war on drugs.

Beginning rhetorically, much like Nixon’s War on Drugs, Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign attempted to discourage the youth of America from the temptations of drug experimentation. The campaign grabbed viewers’ attention and helped to reinforce national attitudes about drug use. Televised messages spoke mainly to adolescents who never used drugs, rather than addressing those who already struggled with usage and addiction.

In 1980, the homicide rate in Philadelphia was 22.5 for every 100,000 people, making it the highest for the nation’s ten largest cities. Changes in the drug trade resulted in access to some of the purest heroin and cheapest cocaine compared to the rest of the country. The advent of crack-cocaine and the ensuing wars over drug turf were typically settled with automatic weapons. The murder rate in the 1980s rose largely due to violent conflicts over the acquisition and sale of drugs, particularly crack-cocaine.15

Perhaps the most significant event in Philadelphia during the 1980s, was the MOVE bombing of 1985. The radical anarchist group MOVE had started as a black liberation group in 1972 when founded by John Africa. Living together in a house in West Philadelphia, the members did not clash with law enforcement until 1978, when police attempted to evict them from their house. In the ensuing chaos, one police officer was killed by gunfire. Nine members of the group were sentenced to 100 years in prison. The remainder of the group moved to a row house on Osage Avenue in 1981.

MOVE turned the new residence into a veritable fortress, complete with a fortified bunker on top of the roof. Constantly spouting profane political propaganda at all hours, neighbors complained and eventually began to lobby City Hall, citing noise complaints and the illegal possession of firearms. Eventually, the mayor and police commissioner, Wilson Goode and Gregore J. Sambor, respectively, came to view MOVE as a terrorist organization.

On May 13, 1985, the police arrived at the house with arrest warrants. Shooting began not long after, prompting police to respond with more than 10,000 rounds in 90 minutes. Eventually, Sambor gave instructions for the fortified house to be bombed. A satchel bomb was dropped from a state police helicopter onto the roof of the house. The house caught fire almost instantly; firefighters were told to let the fire burn. The flames quickly engulfed the entire block of row houses, eventually destroying 61 homes on Osage and the surrounding streets. At the conclusion, 11 were dead, including found John Africa. Five children were among the casualties.16

In the wake of the bombing, Commissioner Sambore resigned. Mayor Goode’s reputation was forever tarnished due to massive public backlash from the ordeal. While Sambore and Goode believed they were doing the right thing at the time, the fallout of the MOVE bombing exacerbated the already-tenuous community-police relations in the city, especially in West Philadelphia.17

Federal policy provided more resources to government drug agencies. In 1982, the administration and Congress provided $125 million to create twelve new regional drug task forces to be staffed by over a thousand new FBI and DEA agents. This was coupled with rising rates of federal drug prosecutions. Drug prosecutions at the federal level rose by 99 percent from 1984-88. The focus of the prosecutions also shifted; more attention was now placed on street level dealers. The increase in drug prosecutions in the 1980s reflected more of a shift in political ideology rather than a significant rise in drug offenses. In other words, federal prosecutions increased because more attention was being paid to drug offenses, rather than an actual rise in occurrences. Another cause for the rise of incarceration was the massive hike in violent crime during the crack years.

In 1984-85, crack-cocaine broke ground in many inner-city neighborhoods. The mixture of powder cocaine, water, and baking soda was inexpensive, packaged in small portions and quickly became a drug peddled primarily to low-income urban citizens. The Reagan administration passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988, which exacerbated the already-tumultuous kit of national policies; the act created more mandatory sentencing laws and claimed that America would be “Drug-Free” by 1995. A five-year mandatory minimum was established for anyone convicted in a federal court for possession of 5 grams of crack-cocaine. Perhaps most egregious of all, the act created a 100:1 sentencing disparity for crack-cocaine; the same mandatory minimum for possession or trafficking of crack-cocaine would require 500 grams of powder cocaine. In hindsight this policy has been seen as discriminatory against African Americans, given that African Americans were more likely to use the cheaper and more readily available crack rock form.18

The drug war has had a severely disproportionate impact on African Americans. “The seemingly arbitrary nature of the criminal justice system, from the moment the police stop a man to the moment his parole sentence ends, leaves a young man feeling that he cannot actively determine how his life turns out.”19 Crimes such as burglary are usually treated in a reactionary capacity; victims or observers report the crime as it is happening or in the aftermath. Drug arrests, on the contrary, elicits far more discretion on behalf of police. Police officers decide where and when they will seek to make drug-related arrests and to what extent they will enforce drug laws. “In the ghetto, you are not presumed innocent until proven otherwise. Rather, you are presumed guilty or at least suspicious…”20 For people of color, the War on Drugs was as much a war on constitutional rights and civil liberties.

Looking at drug arrest data from 1980-2000, an increasing trend is observable, with a rapid spike around the time the Anti-Drug Abuse Act was passed. In 1980, there were 581,000 arrests for drug offenses, reaching 1,090,000 by 1990. Most data also show that drug abuse had been declining since 1979. Further analysis of FBI data shows that in 1980, African Americans accounted for 21 percent of drug possession arrests nationally. African Americans amounted to just 13 percent of the population at the time. By 1992, African Americans represented 36 percent of those arrested for drug-related offenses.21 Along with the 1990s came sentencing reforms that would lock up more people for longer periods of time than anything its predecessors could have conceived.

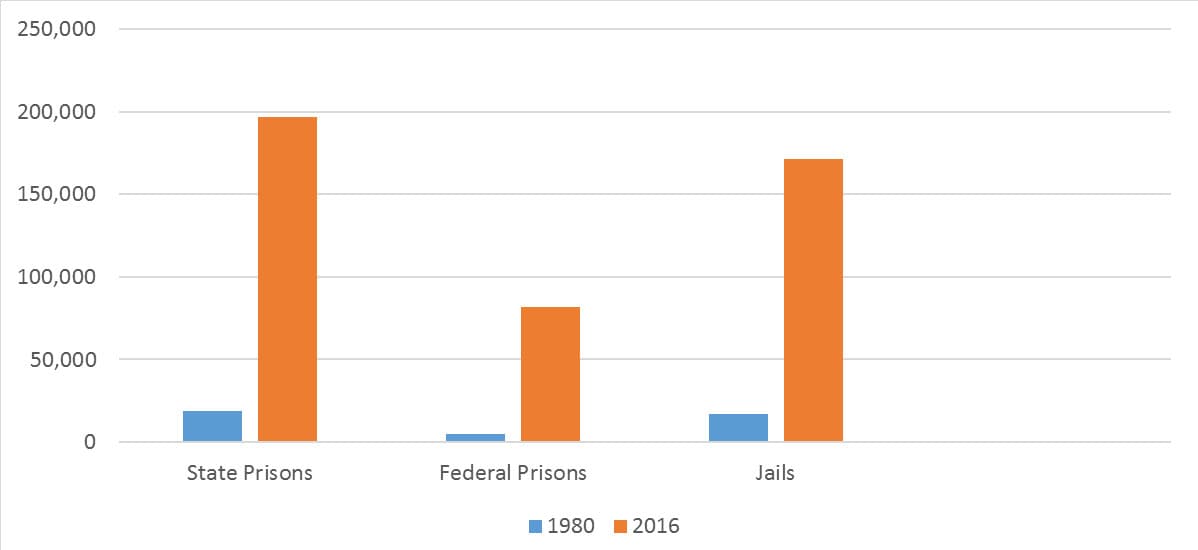

Incarceration Rates for Drug Offenses, 1980 & 2016

After the War on Drugs took shape in the mid-1980s, the aggressive policing and sentencing of drug users fueled incarceration rates like never before.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics

Clinton, Three Strikes, and Mandatory Minimums

Dating back to Barry Goldwater’s presidential campaign in 1964, the “tough on crime” attitude had largely been proprietary to conservatives. That changed in 1992 with Bill Clinton. The newly-minted Democrat strategy of appearing tough on crime would have drastic legal implications for those arrested and convicted of serious offenses. The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, or Omnibus Crime Bill, would change the face of criminal justice in the United States like never before.

Emerging as a “new” Democrat, Clinton found that traditional Democratic strategies of appealing to the working-class and the poor would be ineffective. The real political capital was to be found in middle-class, suburban voters. Despite the fact that the majority of crime victims were minorities themselves, white suburbanites often pushed for harsher criminal penalties. Adopting the tough-on-crime stance of the right, it became a bipartisan issue. Clinton learned from the defeat of Michael Dukakis in the 1988 presidential campaign. Dukakis had advocated in favor of weekend furloughs for convicted felons, at great personal cost. When Willie Horton was released on a weekend pass, he raped a woman and brutalized her fiancé. The opposition used this chain of events to disastrous effect against Dukakis, costing him the election. It was clear: no politician could possibly appear to be soft on crime and hope to gain any sort of footing.

In early 1992, Clinton flew to his home state of Arkansas to oversee the execution of a mentally impaired black man. Ricky Ray Rector was so unaware of what was about to happen that he asked if he could save the dessert from his last meal for the following morning. Clinton extolled his tough-on-crime mentality following the execution.

Clinton did offer a nuanced approach toward crime policy, far more so than his predecessors’ excessively punitive measures. Campaign speeches often elaborated on the need for drug treatment, coupled with an increase of 100,000 police nationwide to coincide with community policing initiatives. In contrast to Clinton’s later policies, there was growing support for alternative methods to incarceration in the early 1990s. Furthermore, there was also nationwide notice of the significant racial disparities within every level of the criminal justice system. State courts and the American Bar Association conducted examinations into the causes and remedies for the racial disparities in prisons and jails across the country. Congressional hearings continued to raise levels of public attention.

After suffering setbacks with his first two nominations for Attorney General, Clinton finally found his champion in Janet Reno. Reno began her tenure as Attorney General by touring the country and preaching about systemic solutions to incarceration. Public perception of Reno was positive and it appeared as though national perspectives on crime and punishment were making positive progress. Unfortunately, this was not a sign of progressive reforms to come; policies gradually shifted in the coming years.

Clinton’s “tough on crime” attitude was rapidly solidified by a number of high-profile crimes in 1993. The murder of a twelve-year-old girl in California, Polly Klaas, shootings perpetrated by a gunman in Long Island, and the murder of Michael Jordan’s father all exacerbated national perceptions of violent crime. Because these crimes were random and heavily televised, middle-class suburb-dwellers felt that they, too, could be victims of such attacks. Between 1992-93, television coverage of crime more than doubled. Murder coverage tripled, despite the fact that crime rates had remained unchanged from previous years.22

The Clinton administration was now faced with a decision on how to formulate crime policy. While on the campaign trail Clinton had endorsed progressive reforms to criminal justice policy, however, he also supported punitive measures, such as the death penalty and boot camps, among others. As interest in Congress over more federal crime legislation was developing, Clinton had to decide what his administration’s position would be. The Clinton administration, eager to show that it could be tough on crime, endorsed the idea of a “three strikes” law after one was passed in Washington state in 1993. Clinton’s 1994 State of the Union address discussed it as well, once again bringing crime policy to the forefront of the national stage.

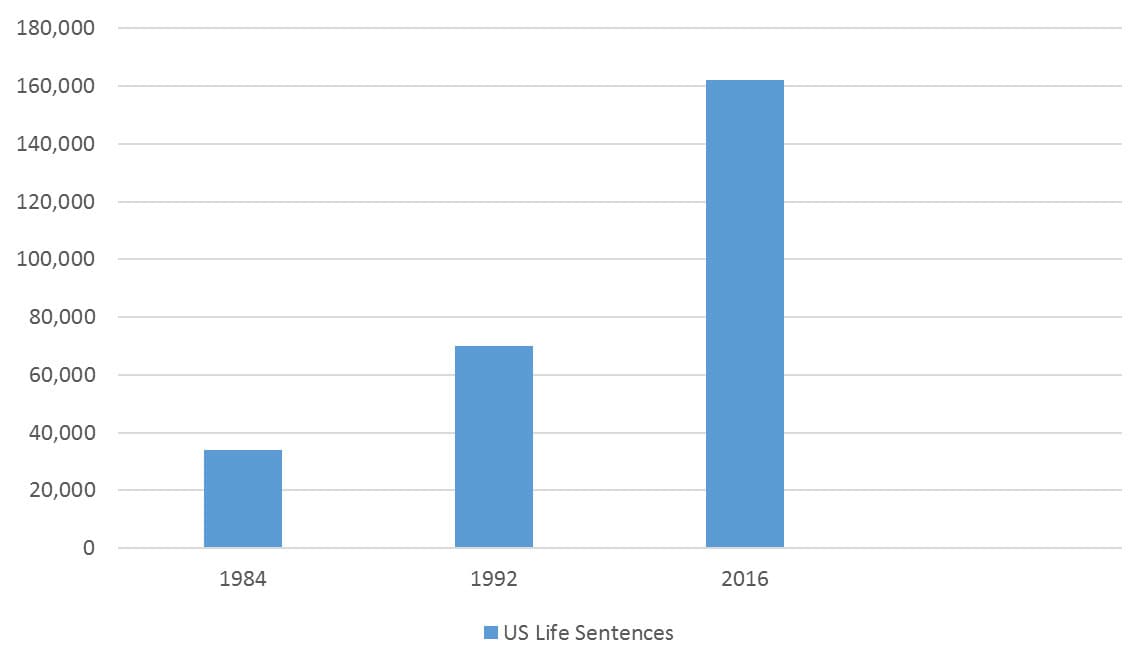

Number of People Serving Life Sentences, 1984-2016

The number of people serving life sentences increased dramatically from 1984-2016. Due to policies enacted via the Omnibus Crime Bill, among others, the number of “lifers” quadrupled nationwide from just under 40,000 in 1984 to over 160,000 by 2016. Many states adopted similar crime policies after the passage of the bill in 1994.

Source: The Sentencing Project

In Philadelphia, violent crime consistently numbered in the four-hundreds throughout most of the 1990s. There were 384 homicides in the city in 1988. Murders peaked in 1990 at 497, but then fell variably from year to year, hitting a low of 296 in 1999.23 During this period the number of arrests for drug abuses of heroin/cocaine and marijuana began at 599,500 and 391,600, respectively. Peaking in 1989 at 732,600 and 399,000, by 1999 the arrest rates had flipped, with 528,000 heroine/cocaine-related arrests and 704,800 for marijuana.24

There was a significant rise in incarceration rates in Pennsylvania during this timeframe. The prison population increased steadily from 1988 onward, beginning at 17,833 and more than doubling to 36,525 by 1999. Compared to federal numbers, the trend matches; 42,738 in 1988 and 114,275 incarcerated by 1999.25 There are approximately 5,100 people currently serving life sentences in Pennsylvania prisons. Compared to national data, Pennsylvania has the second-highest number of people serving life without parole. Furthermore, life without parole disproportionately targets people of color, especially in the state of Pennsylvania. 65% of those serving such sentences are black, compared to around 50% nationally.26

One major cause of prison growth that cannot be overlooked is the role of the prosecutor. As John F. Pfaff notes in Locked In, “…over the 1990s and 2000s, crime fell, arrests fell, and time spent in prisoned remained fairly steady. But even as the number of arrests declined, the number of felony cases filed in state courts rose sharply.” Generally speaking, prosecutors have largely been ignored by those attempting to enact reform in the criminal justice system. The number of line prosecutors, (those who actually try cases), has increased to over 30,000 nationwide within the last thirty years. Even though violent and property crime rates have fallen by 35% between 1900 and 2007, we find ourselves with more prosecutors than ever before, and they remain largely unchecked insofar as their role in sending individuals to prison. Prosecutors have immense discretionary power and often force the hand of individuals who would not dare go to trial when facing multiple felony charges which could result in decades of prison time. Rather than serve a long term, with the risk of multiple felony convictions, many opt to take a plea deal, pleading guilty to crimes that come with a set of lesser charges and sentences. Beginning in 1974, there were about 9 prison admissions per prosecutor. In 2007, the last year of trustworthy data, there are approximately 23 admissions per prosecutor.27

The Omnibus Crime Bill mostly covered violent offenses. Congress eventually passed a six-year, $30 billion package in favor of expanded law enforcement and incarceration measures. $8 billion went towards prison construction, including incentives for states to similarly get tough on crime in order to qualify. $8.8 billion went towards policing. The package also expanded the federal health penalty and took away Pell grants for higher education to prisoners. The “truth in sentencing” provision was yet another attempt to undermine indeterminate sentencing by creating financial incentives for states to increase prison terms. Under these provisions, a convicted felon sentenced to 15 years would serve the entirety of that term. Twenty of years of “tough on crime” policies had created a bloated prison system, rife with overcrowding and racial inequities. The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act served as the final icing on the cake. Mass incarceration was here to stay.

The Legacy of Mass Incarceration

Beginning with the rhetorical war on drugs, and continuing beyond the 1990s, prison populations have risen dramatically. For every 100,000 people in the United States, 670 are incarcerated.28 The total prison population as of 2016 was 1,458,173 people. More than 80,000 people are in prison at any given time in Pennsylvania. The state spends more than $2.4 billion to lock up its citizens and the average cost of incarceration per capita is more than double what it would cost to give someone a college education.

African Americans make up more than 50% of the prison population, despite the fact that only 11% of the state’s population is Black. Around a quarter of Pennsylvania’s prisoners are in jail awaiting trial. Awaiting their day in court, they have yet to be convicted of anything.29 6.1 million Americans are unable to vote due to their status as a convicted felon. 1 in 13 African Americans has lost their right to vote, compared 1-in-56 non-black voters. 48 states do not allow prisoners to vote, 34 states disenfranchise those on probation or parole, and 12 states deny the right to individuals with a prior felony conviction.30 Astronauts can submit an absentee ballot from outer space but convicted felons in most cases are voiceless in the democratic process.

While the legacy of mass incarceration is indeed restrictive, progress is being made in cities like Philadelphia to reduce the punitive measures often employed. Philadelphia is currently enacting radical criminal justice reforms that may come to serve as a national model. District Attorney Larry Krasner is attempting to end mass incarceration in the city and bringing balance back to sentencing. Police are diverting drug arrests to treatment rather than prison – so far none enrolled have been rearrested. Krasner is also no longer asking for cash bail for low-level offenses, preventing those being held or awaiting trial to suffer needlessly in a holding cell. Krasner has also implemented procedures to force prosecutors to calculate and explain to a judge the financial cost of the sentences they recommend in an effort to hold often-unregulated prosecutors more accountable There is agreement among the top Philadelphia justice systems that Krasner’s reforms and a $3.5 million grant from the MacArthur foundation is helping to reduce recidivism and mass incarceration.31

Larry Krasner assumed the office of District Attorney on January 1, 2018. Krasner, a former civil rights and criminal defense attorney, is possibly best known for suing police officers. After the previous District Attorney, Seth Williams declined to run for a third term after being indicted on corruption charges, Krasner used this as part of his platform, to great effect. Campaigning on a platform of ending mass incarceration, cash bail and the death penalty, Krasner defeated his opponent, Republican Beth Grossman, three-to-one in votes. Krasner took the majority in all but 12 of the cities wards, securing the vote of many of the individuals his reforms hope to benefit.32

Under Krasner, the Conviction Review Unit has been revamped in an effort to overturn wrongful incarceration. The “do not call” list of officers suspected for lying at any point in a criminal procedure has been expanded and made public. Krasner also plans to repair the broken plea bargain system by offering deals at the low end of sentencing guidelines; most nonviolent crimes below $50,000 with no prior convictions will instead result in low sentences or probation. By 2020, the 91-year-old House of Corrections jail is being closed, due to a 33% reduction in the inmate population. Much of this is due to reform efforts in Philadelphia, many led by Krasner.

The Philadelphia District Attorney’s office will also seek to decriminalize marijuana possession at the local level. The War on Drugs has seen a large number of nonviolent drug offenders incarcerated over minor drug possession. The effective decriminalization of marijuana possession in nonfederal cases will alleviate much of the morass plaguing the courts and jails. Possibly the most radical reform, Krasner is now requiring prosecutors to calculate the amount of money a sentence would cost before recommending it to a judge. Putting the financial cost in visible monetary quantifications will hopefully avoid unnecessary incarceration spending in the face of less expensive alternatives.33

The effects of continually shifting rhetoric and policies on criminal justice have had devastating, far-reaching effects. Since the 1960s, increasingly punitive attitudes at every step of the legal process have disenfranchised convicted felons, with African Americans represented disproportionately. Millions are in jail for nonviolent drug offenses, some serving life sentences due to harsh “three strikes laws.” When Charles Dickens visited Eastern State Penitentiary in 1842, he claimed the “…rigid, strict and hopeless solitary confinement…[was] cruel and wrong.”34 He would be appalled to see the state of affairs in just one American prison today, let alone nationally. Although the problem of mass incarceration in the United States has been a series of gradual changes, reform appears to be on the horizon. It yet remains to be seen on a large scale, but if Philadelphia serves as a national model, reform policies may indeed take hold and allow the healing process to begin.

Comments: