Resources

To introduce the United States History portion of the unit, I will show a compilation of historically racist imagery. The use of lecture with effective questioning techniques will get students to make connections between the artifacts, exemplary artworks, and poems. The poems as well as the works of art all share the desire to uncover the truth. In my resources, artists and poets use their work to dig deep, exploring despair, joy, frustration, and beauty. Hosting a guest artist who is currently working through these topics will supplement and further learning. Literary and visual art resources will include living and non-living poets and artists. Some but not all poetry examples will be ekphrastic.

Artifacts

Students will make the connection between laws passed during Jim Crow and the racist artifacts from the same era that were made as a way to perpetuate the stereotypes regarded as truth by many whites.

In 1828, after seeing a black man perform a song referring to himself as Jim Crow, Thomas Dartmouth “Daddy” Rice, a struggling white actor in New York, appeared on stage as a character of the same name. Rice’s Jim Crow character was an exaggerated and stereotypical black man. One of the pioneers of “blackface” makeup, Rice used the ash from a burnt cork to appear black onstage in minstrel shows. By the early 1830’s, Jim Crow was a stock character. Rice and his cohort of other blackface performers helped to popularize the notion that blacks were lazy and sub-human. Jim-Crow era objects reflected and molded whites’ attitudes towards African Americans. These stereotypical images of black people fortified the idea that blacks were not fit to: assimilate into white schools or neighborhoods, partake in relationships with whites, break bread with whites, or speak in a casual and informal tone with whites.15

Between 1850 and 1870, minstrel shows were exceedingly popular. By the late 1830s, the phrase Jim Crow was synonymous with the words coon or darkie. Beyond that, Jim Crow transformed in meaning to also encompass the racial system in place between 1877 and the mid 1960’s. Plessy v. Ferguson, a landmark Supreme Court case, upheld the legality of racial segregation and the way of life in the Jim Crow south. Laws supported the notion that blacks were second-class citizens. Etiquette norms were stringent too. Black men could not offer to shake hands with a white man. Blacks could not show public displays of affection. Even while driving, blacks were subordinate - whites had the right- of-way at all intersections.16

Caricatures

From the 1830s to well into the mid-20th century, blacks were visually represented in ways that mimicked minstrelsy. Pitch-black skin, large and exaggerated mouths, lips - sometimes white and sometimes red - and wiry or unruly hair were all characteristics of racist depictions of blacks.

In 1889, Charles Rutt and Charles G. Underwood coined the name Aunt Jemima to pair with their development of a self-rising flour product.17 Aunt Jemima, the quintessential mammy, was wholesome, overweight, and sexually non-threatening. Caricatures, although they have morphed, remain in place today. Aunt Jemima is no longer portrayed as a large-lipped, head scarf-wearing housekeeper. On packaging found in supermarkets today, Aunt Jemima appears as an attractive and content housewife or maid – her character is intentionally ambiguous.

If the caricature was meant to depict a household worker, like the mammy or the Tom, docility and faithful subservience would be evident in their facial features and other visual elements.18 The contentedness of the mammy and Tom represented in advertisements, postcards, and packaging was not accidental. These caricatures were created to be further the notion that if blacks were content at the bottom of the social hierarchy, then slavery and Jim Crow era laws were just and moral. Attitudes did inform the manufacture of anti-black caricatures and stereotypes, but more insidiously, the stereotypes were created to maintain and perpetuate them. Each stereotype – that blacks were dangerous, dumb, and subhuman - was designed specifically as a tool to ensure that blacks were perceived to inferior to whites in all ways. Stereotypes and caricatures, in effect, functioned as political propaganda.

Visual Art

The exemplary artists I’ve chosen for this unit are all African American. Each uses a different medium to make commentary on some area of their experience being black in America. The majority of the artists I chose are living contemporary artists. This intentional choice reinforces the notion that these issues are relevant today and that artists are grappling with them. Visual art exemplars in this unit work with issues of representation, cultural identity, black excellence, fury at racial injustice and the beauty and power of resilience.

I will show selected artworks by the following artists: Kehinde Wiley, Paul Rucker, Hank Willis Thomas, Elizabeth Catlett, Kara Walker, Alison & Betye Saar, Carrie Mae Weems and Titus Kaphar. The thematic focus of the selections will be the artists’ (re)presentation of anti-black caricatures and/or attitudes and the ways in which these artists achieve that. We will also look at how each artist explores personal and cultural identity.

Fig. 1 Alison Saar, Sea of Moisture, Bronze, 2008

Alison Saar comes from a family of artists and radical thinkers. Her mother, Betye Saar, was an assemblage artist during the Black Arts Movement of the 1970s, which was an artistic offshoot of the Black Panther Party. Like her mother’s, much of Alison Saar’s work uses vehicle for activism.

Sea of Moisture is a sculptural wall hanging depicting the back of a human torso. Only two colors are visible in the piece – black and turquoise blue. Both of these colors are patina, which is the result of a chemical change to a metal surface. It is a process often employed by artists working with metal to add color or textural elements. From this, we might infer that this person has undergone a change, perhaps a superficial one. The drops of water could represent the ocean, as the title suggests. They could also be tears, maybe both. The bottom left of the back has a large cut that is reminiscent of a whipping welt. Marks and scars like these were extremely common among slaves – evidence of punishment for even the smallest offense. This piece could be interpreted as a representation of African American resilience and reckoning with the past - the beads of water are literally rolling off the back, being let go. Additionally, this piece has a moody quality. It evokes a spectrum of feelings – relief, introspection, and inner strength.

Made of bronze, we can assume this piece is physically heavy. The things that cause us physical and emotional pain are too.

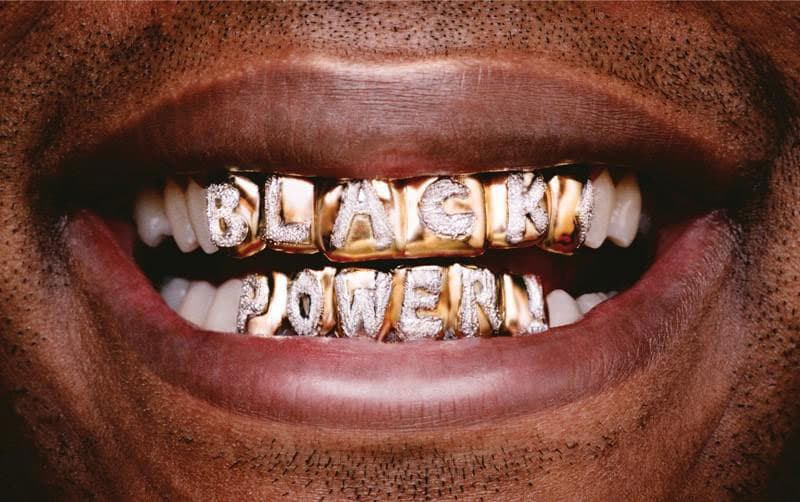

Fig. 2 Hank Willis Thomas, Black Power, photograph, 2006

Hank Willis Thomas is a conceptual artist living in New York. His photograph entitled Black Power depicts a close-up of black man’s smiling mouth. The subject is wearing a gold grill that has “BLACK POWER!” spelled out in what appear to be diamonds.

Grills are considered jewelry and made in a variety of metals often inlaid with precious stones. Today, grills are status symbols and fashion statements for rap artists and aficionados. As an object of luxury, the wearing of a grill communicates to onlookers the wearer’s ability to purchase such a lavish item. The excess capital necessary to obtain status symbols like this is evidence of upward mobility and financial success.

If my focus moves from the words on the teeth to the photograph in its entirety, I see a man’s smile. A smile is an obvious indication of happiness, but perhaps in this case, it is duplicitous. Maybe he is thinking, “Despite all that I was up against, I found power in my blackness – and it paid off.” In their 2018 song “Walk It Talk It”, widely popular trap music trio Migos substantiate this with the lyric, “get your respect in diamonds.”19

There seems to be an obvious connection between Thomas’ interest in the mouth and a reference to the exaggerated mouths of racist caricatures. Illustrators would hone in on their renditions of giant mouths and lips on the black individuals they drew. Because we cannot see the subject’s eyes to analyze his expression, the smile is ambiguous. The nod to racist representations gives me reason to believe his smile could just as easily be steeped in irony as it is sincerity.

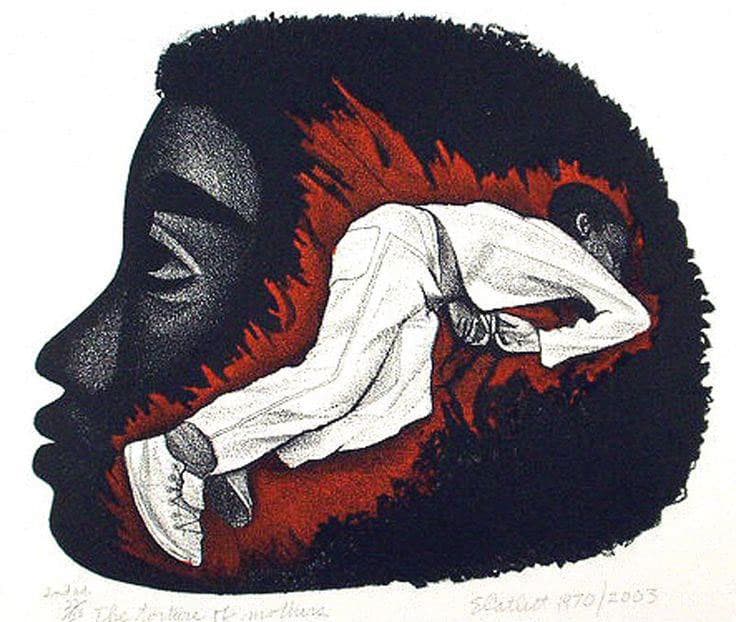

Fig 3. Elizabeth Catlett, The Torture of Mothers, Lithograph, 1970

Elizabeth Catlett was a highly regarded figure in the field of sculpture and printmaking.

Referred to by Maya Angelou as a “queen of the arts,” Catlett used her work to speak to social issues, particularly those involving African American women. In Samella Lewis’ book “African American Art and Artists”, Catlett says “I have always wanted my art to service black people – to reflect us, to relate to us, to stimulate us, and to make us aware of our potential.”20

Printmaking is a term that encompasses many different processes. This print is an example of a lithograph. Using a flat surface, typically stone, and a greasy drawing implement, lithography exists because of the immiscibility of oil and water. Ink is applied to a greasy image on the surface of the stone. The blank areas of the stone, which hold moisture, repel the ink and result in a print of the exact image that was drawn. Printmaking appeals to many artists because it provides multiples of an image. Why go through the hassle of drawing an image over and over when you can draw it once and print it an infinite number of times?

Although this image was made in 1970, Catlett’s The Torture of Mothers could be printed again today – and would still be just as relevant. Black men and boys are dying at the hands of police at an alarming rate. Black mothers warn their children of what dangers exist in the world for black youth. For a black child even in the most innocuous of interactions with law enforcement, anything is possible.

In the image, this woman’s son is literally on her mind – his entire body, surrounded by blood (or fire), is cradled inside of her. Is she agonizing over his murder? Or is she fixated on the possibility of such a fate? Dwelling on thoughts of my family members or myself being murdered senselessly is not something I typically do – this is a privilege clearly not afforded to this mother and others like her. The violence African Americans face in our country remains a torturous reality, unyielding and ongoing, forty-eight years after the creation of this artwork.

Works of Art for Students

In addition to the three works of visual art previously mentioned, I will include the following pieces in my unit:

Betye Saar, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, 1972

Hank Willis Thomas, Raise Up, 2014

Kehinde Wiley, Prince Albert, Prince Consort of Queen Victoria, 2013

Carrie Mae Weems, The Kitchen Table Series, 1990

Titus Kaphar, Space to Forget, 2014

Kara Walker, The Marvelous Sugar Baby, 2014

Rebel Leader, 2004

Poems

Bryan Stevenson asserts, “You can't do reconciliation work, you can't do restoration work, you can't do racial justice work, you can't create the outcome that you desire to see until there has been truth-telling. And truth-telling has to happen when people who have been victimized and marginalized and excluded and oppressed are given a platform to speak, and everybody else has to listen.”21 The poetry portion of this unit will be our opportunity to listen carefully and internalize the words of black poets.

Poets whose work we will study will focus on topics like truth telling, fear, sorrow, power, and redemption. The variety of tones present in this collection of poems will mirror that of the visual art. These pieces will run the gamut of human emotion. Written responses and reflections are not uncommon in the high school art curriculum. But why use poetry, rather than prose, to get students to respond to visual art? Poems open up the possibility of nuance and give the writer space to say what cannot be said in prose. Reading poetry offers feelings of solidarity and relief. Not only are we able to use poetry to help us confront suffering, it helps us investigate the relationship between suffering and beauty. It’s a natural vessel for discussions about social principles. It teaches us to not be constrained by our imaginations.

My assumption is that the majority of the class will choose to write in free verse, so several of my examples will reflect that. Getting teenagers to avoid clichés and ready-made phrases will be a significant part of the challenge in this portion of the unit. Through our exploration and writing of poems, students will begin to understand not only the nuance of language, but that words are, contrary to popular belief, not interchangeable.

Fig. 4 Paul Rucker, Storm in the Time of Shelter

Guest Artist

In considering exemplary artists I would use in this unit, the first artist whose work came to mind was Paul Rucker. I became aware of Paul Rucker’s work through a workshop centered on the theme “Clearing Roadblocks Together: Critical Conversations on Diversifying Art Education”. Paul spoke at length about the necessity of working together to move our field towards inclusivity and anti-racist pedagogy. I knew immediately I wanted to work with him.

Often using unlikely combinations of objects and images, all of Paul Rucker’s work brings inequality and the desperate need for change into focus. Recently, I was fortunate to see his work at Richmond’s new Institute of Contemporary Art and one piece in particular took hold of me. When I stepped into the gallery, the visual violence of his work was arresting - both literally and figuratively – inside, pieces explore the relationship of slavery to the modern day prison industrial complex. In an installation of particular interest, Paul showcased bespoke Ku Klux Klan robes, made using fabrics in unlikely prints and patterns like Kente cloth and camouflage.

At the time of this writing, Paul Rucker is a TED Fellow as well as a Virginia Commonwealth University iCubed Visiting Arts Fellow embedded at the ICA in Richmond. Mr. Rucker has graciously agreed to be a guest artist in my classroom during this unit. His visit will allow students an opportunity to hear about his approach to these topics and themes as they relate to our studies. Students will be able to interact with an artist whose work deals in the very content we will be studying. Because the nature of his work is so closely related to what we will be doing in the classroom, Paul Rucker’s visit will function as a resource.

Comments: