Key Content

Definition of Ekphrastic Poetry

I believe it helpful to understand the concept of ekphrasis. In addition to understanding the concept, it is also essential to understand the intention of the poet. These understandings will allow you to develop a framework of skills necessary for teaching ekphrastic work. The simple

definition of ekphrasis is “a written piece in response to a work of art.” According to the Poetry Foundation, “An ekphrastic poem is a vivid description of a scene or, more commonly, a work of art. Through the imaginative act of narrating and reflecting on the “action” of a painting or sculpture, the poet may amplify and expand its meaning.”4 However, there exist various types of ekphrasis, along with multiple approaches, and purposes (objectives) for this kind of writing.

As I learned in the seminar led by Paul H. Fry, entitled “ Poems about Works of Art, Featuring Women and other Marginalized Writers,” there are three types of ekphrastic poetry: notional ekphrasis, actual ekphrasis, and unaccess[i]ble actual ekphrasis. Notional ekphrasis is literature based upon an imagined work of art. An excellent example of this type of ekphrasis is “Ode on a Grecian Urn” by the romantic poet John Keats. The urn in Keats’s poem cannot be found anywhere other than in his imagination. Actual ekphrasis is a written response to a piece of art that we can find and view. One such work that we studied in seminar was “Musee de Beaux Arts” by W. H. Auden written in response to Pieter Brueghel’s “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” in which the writer describes for us a specific moment in time showing the indifference of others to the suffering of another individual, of inconsequence to them. The fall of Icarus is the tragedy of this work, he having flown too close to the sun and melted his waxen wings. Unaccess[i]ble actual ekphrasis is literature written in response to a work to which we do not have access, perhaps because it is lost. Any one of these forms of ekphrasis can be an effective tool used to introduce poetry to students.

Actual ekphrasis is the most obvious choice for me, as a Language Acquisition teacher, because I anticipate that my students will struggle with comprehension of the poem in the target language. This variation of ekphrasis will provide a clear frame of reference and provides an entry into the poem. Reading and comprehending literary works in Spanish are intimidating enough for my eighth grade students, even more so when that literary work is a poem. Introducing Spanish poetry through ekphrasis will allow my students to seek out lines in the poem that refer to the work of art and from there they can begin to piece together its meaning along with the poet’s intent.

La Calavera Catrina

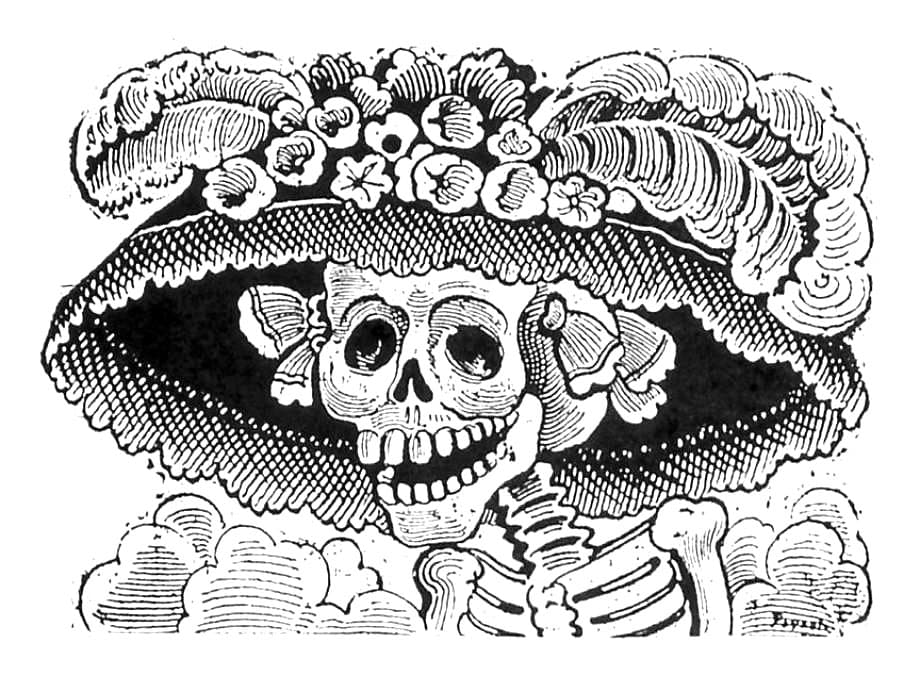

José Guadalupe Posada, the creator of La Catrina, is one of Mexico’s most famous political printmakers and engravers. His work influenced artists throughout Latin America because of its satirical nature and social engagement. He used calaveras, skulls, and bones to pursue political and critical analyses. La Catrina, Figure 1, is Posada’s most famous calavera and is arguably Mexico’s quintessential image of death.

Figure 1 La Catrina by José Guadalupe Posada

The use of the skull in political satire emerged in Mexico during the early 1900s, around the time of the Mexican Revolution. Posada received his inspiration for La Calavera Catrina from Aztec mythology, specifically from the deity Mictecacihuatl, goddess of death, and Lady of Mitlan, who along side her husband ruled the underworld. According to Aztec mythology, she was the keeper of bones in the underworld and presided over the month-long celebrations honoring the dead.5 The original depiction of Posada’s Catrina was La Calavera Garbancera. Garbancera derived from the garbanzo sellers, who, being poor, pretended to be rich and wanted to hide their indigenous roots. This group of merchants pretended to have the lifestyle of Europeans. As the Mexican Revolution picked up steam, La Calavera Garbancera evolved into La Calavera Catrina,

catrina being the feminine form of the Spanish adjective catrín, meaning well-dressed or dandy. La Catrina characterizes the elite of Mexico as a skull wearing a French plumed hat; white-washing, or washing out their native roots for European ones. The white face painting is said to be their attempt at being white.6 Posada’s message was,“Regardless of what you wear or how white you try to dress and be, your bones are native.”7

The satirical character in the French plumed hat appears again in 1947 in the work of Mexican painter Diego Rivera in which he gave her a body and dressed her in fancy clothing. At the center of this mural, “Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en Alameda Central” (“Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park”) La Catrina wears a feather boa around her neck, made of sheaves of withered corn with a snake’s head on the end of the right side. Fangs are projecting from the snake’s mouth. The left side of the boa ends with a snake’s rattle reminiscent of Mictecacihuatl, the Aztec goddess of death.

“Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en Alameda Central” (“Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park”)

In 1947, ten years before his death, Mexican artist Diego Rivera, famous not only for his many paintings but also for his murals throughout his homeland and the United States, was commissioned to paint a mural in the dining hall of the Del Prado Hotel at the center of the Mexico City’s elegant life. The hotel is situated across from Alameda Park. This partnership of painter and hotel was a natural one as they both desired to attract wealthy American tourists. It was these Americans who were purchasing Diego’s work -- the young American girls who were seeking their brief moment of fame in his presence -- and the hotel was seeking the business of these wealthy patrons.

Diego’s increasing preoccupation with the thought of his death rapidly approaching, and the location of the Del Prado Hotel across from the Alameda blend together to shape the theme of his mural “Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en Alameda Central,” Figure 2. At this point in his life, Rivera took great pleasure in his skills as a storyteller. He employed his creative energy to the creation of his autobiography, reliving his life as a splendid myth. This dream-like composition is composed of figures drawn from children’s history books, national legends, childhood thoughts, memories and fantasies, all of which could only coexist in a dream.8 Diego’s daughter Guadalupe explained her father’s imaginary tales saying, “My Father was a storyteller and he invented new episodes of his past every day.”9 This fresco is also said to be Rivera’s personal response to the question of one of his personal historical heroes, Ignacio Ramirez, who was an intellectual leader of the Reformation under Benito Juarez: “Whence do we come? Where are we going?”10

Figure 2 Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en Alameda Central by Diego Rivera

As a child, during the reign of Porfirio Díaz, Rivera would frequent La Alameda with his parents or aunts and uncles. Often times they would rent a seat for twenty-five or fifty centavos by the bandstand to enjoy the music of a military band. The park was visited by respectable ladies and gentlemen and their children attired in their Sunday best. Peddlers strolled the park with their wares: brightly colored balloons and pinwheels, sugar-sticky treats, and a rainbow variety of drinks. As Diego remembers, the police were ever present to keep out the beggars, pick pockets and the shabby Indians. As an adult, on holidays, Diego would sometimes stroll the park with his wife and daughters.

Alameda Park has a rich history of its own which Rivera incorporates into his work. At one end of Alameda, during colonial times, there had been a monastery, where according to tradition, the Inquisition burned its victims alive at the stake until it was mandated to end this activity due to the horrifying smell of burning flesh in the park and surrounding areas. Also in this square, President Santa Anna, in 1848, betrayed the country and handed it over on a silver platter to the Yankee invaders.11 On December 4, 1914 Emiliano Zapata and Francisco “Pancho” Villa occupied Mexico City and camped on the Alameda.

The central figure of Rivera’s densely populated mural, La Calavera Catrina, stands holding the left hand of a young Diego at about the age of ten. The boy knows that he can trust Catrina because she will accompany him throughout his life and beyond into death.12 The child has a toad climbing out of one pocket while a snake emerges from another. To the left of La Catrina is the image of the engraver and great artistic mentor of Rivera, Jose Guadalupe Posada with whom the Grande Dame of Death holds her other hand. Behind the boy Diego stands his third wife Frida Kahlo, with a protective hand on his shoulder. In her other hand, Frida holds a small sphere on which are painted the symbols of yin and yang, the two complementary forces that make up all aspects and phenomena of life. To the child’s right, in plumed hats, are Rivera’s two daughters depicted as elegant adult ladies.

The width of “The Dream…” measures over four times its height and is crowded with over 150 figures, each one significant in Mexican history or in Rivera’s own life. The work is divided into three equal parts from left to right and three horizontal planes of depth. The narrative of Mexico’s history reads chronologically across the entire width of the mural from left to right beginning with a tiered assemblage of colonial and early 19th century events and characters, at the center a single level of late 19th century full-length figures, and finally another broad tier composition which depicts early 20th century activities and characters. The foreground row of full-length figures intervenes with the middle ground row of historical characters and events, which keep the present time in mind (the present time being Rivera’s youth as he placed himself near the center of the work). Along the full length of the foreground the average Mexicans of the Díaz era are abandoned and outcast in contrast to the class represented in the work immediately above them. Rivera’s daughter stated that this is a depiction of what he witnessed as a young boy in Mexico City and that it strongly influenced his life and his view of society in general.13 There are four background portraits that are larger than life: Benito Juarez, Porfirio Díaz, Emiliano Zapata, and Francisco Madero. They are of great importance, yet placed just above the middle ground progression of lesser historical figures. These are the personalities who contributed to the formation of a national consciousness and realized the moral value of social responsibility and are thought to have played a role in the development of Diego’s intellectual comprehension of the national issues of his time.14 All of the elements of this single dream are bound together by the arterial branches of the park’s trees skillfully assembled by the artist into well-composed groups blending colorful hues of red, blue, yellow, brown, gray, white, and black, which also adds to the dream-like quality. These elements are also held together by the fact that they are parts of an individual cluster of memories and fantasies in the mind of the creator. Despite the elements of a history so full of bloodshed, failure, tragedy and treachery, and the central presence of death, Rivera successfully creates a festive, humorous, light-hearted mood in this work.

The Alameda piece, of all of the murals that Diego created, is the only work in which he interlaced personal fantasies with autobiography. This mural seems as if it was almost his final act in which he presented his public with a landscape of everything that shaped his character. The irony of Diego Rivera’s life was his decision to return home to Mexico from his time painting in Italy to spread a message for the future of order and hope, and to reinterpret it in terms of the Indian culture. He ended up in the Hotel Del Prado painting “Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en Alameda[,]” painted from the perspective of a ten year old Rivera, representing the corrupt present and the idyllic past with no reference to the future.15

Evolution and Rebirth: Mictecacíhuatl into La Calavera Catrina

The poem that I will be using with my students is “Catrina” by Xánath Caraza. Xánath Caraza is from Vera Cruz, Mexico and currently resides in Kansas City, Missouri. She is a contemporary poet, author of short stories and an educator. Caraza’s poems have been translated into many languages and she has indicated that as a result she thinks about the effects of translation as she writes in Spanish, which alters they way she writes.16 Her works are full of tastes, smells and other sense experiences and because of this they have often been interpreted in the form of visual art.

“Catrina” is a work of actual ekphrasis. While the poem is written in response to an existing work of art, in this case a mural, you will notice that it seems to stray from the artwork. As I learned in seminar, this is not uncommon with works of actual ekphrasis and nonetheless still provides an in for the students to the poem. This work is written in free verse without a regular rhythm or meter and does not contain rhyme. The poem consists of twenty-two stanzas and is divided into two parts; the first section is comprised of seven stanzas related to the Aztec deity Mictecacíhuatl, and the remainder of the work is dedicated to La Calavera Catrina. Just as Rivera presented to us the narrative of Mexico’s history chronologically across his canvas, Caraza presents to us the evolution or transformation of the Aztec Goddess of Death into the Mexican Grande Dame of Death from top to bottom in her poem. Whereas the figure of La Calavera Catrina is strategically placed just to the left of center, in the second third, of Rivera’s mural, Caraza reveals the transformation of Mictecacíhuatl into Catrina in the eighth stanza of the poem, which is the beginning of its second third .

Xánath Caraza employs personification, symbolism, repetition, and colorful imagery in “Catrina” to illustrate the theme of rebirth.

Mictecacíhuatl, fue.

En elegante Catrina,

la del sombrero ancho

se transforma.”

“Mictecacíhuatl, it was.

As an elegant Catrina,

the one in the wide-brimmed hat

transforms herself.

The poet begins her ekphrastic work on Rivera’s “Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en la Alameda” by immediately making the connection between Mictecacíhuatl, the Aztec Goddess of Death, the keeper of the bones, and La Calavera Catrina, the central figure of the Alameda mural for whom the poem is named. Then Caraza reveals to us the theme of rebirth through her effective employment of personification. For example, she makes reference to the “Tree of life” (“Árbol de vida”) telling it to extend its branches/ brazos (arms in Spanish) and allow the rebirth of the spirits. She also describes the tips of the tree branches throbbing with divine fire as if they were alive, like blood coursing through one’s arteries and veins. Remember that Diego bound together all of the elements of his single dream with the arterial branches of the park’s trees into well-composed groups blending colorful hues of red, orange, yellow, brown, gray, white, and black, which seem to give the trees a human quality as various branches appear to be reaching, bending, extending, as if they were alive.

Caraza gracefully weaves the use of symbols that represent rebirth throughout the work. Early in the poem she speaks of roaring water that is born from the caverns (“Río Viejo, fragor de agua brava de las cavernas naces . . .”). In literature, water is linked to the idea of birth, and caves are womb-like. As the caverns give birth to the water, “Butterflies listen.” (“Las mariposas escuchen.”) The poet makes several references throughout the poem to butterflies, most especially to orange ones. These orange butterflies, at times swarms of them, cover one’s heart (“[]cubran su corazón.”), enter on one’s bones (“ Entra el aleteo de la maiposa anarajando en los huesos.”) and become one with “her.” (“se enreda en su pelo se hace una con él.”)

Her use of these insects is rife with symbolism, as it was the belief of the ancient Aztecs that Monarch butterflies were the souls of their deceased ancestors reborn, and permitted by the Lady of Mitclán to visit their loved ones on Earth one day a year. The Aztec people saw the image of a human face in outline on the Monarch’s wings. Even today, in certain parts of Mexico, these butterflies are believed to be the envoys of the gods and the people honor them by burning an incense of wax and copal.

As to the use of repetition, the poet repeats the entire first stanza of the poem about one third of the way into the piece. It is evident through this repetition that she is setting us up for an event; something is about to change. Yet again, Caraza deftly employs the use of symbolism with the rustling of the papel picado that announces Catrina. This rustling is symbol for change; emerging is Catrina with her entourage of orange butterflies. Mictecacíhuatl is no longer; Catrina is now the Grande Dame of Death. The Lady of Mitclán has evolved; she has been given new life. She is reborn, dressed in finery, with a playful personality, and always portrayed with a huge grin. She is a revolutionary woman born of the Mexican Revolution.

The devices of imagery present in this work mostly appeal to the reader’s visual and olfactory senses. For example, the aroma of copal, the sacred incense offered to the gods, and sugar skulls awaken our sense of smell. Copal is similar to the incense used today in some religious ceremonies. The scent of sugar skulls reminds the reader of festive celebrations. “Steaming hot chocolate” (“humeante choclate”), “amber light bathing our walk” (“ambaarina luz bañan nuestro andar”), “flowers” (“flores”), “papel picado,” “and smiles” (“y sonrisas”), all this colorful imagery invades our senses and evokes memories of joy and happiness. This is the message of La Calavera Catrina, reborn from her Aztec ancestor Mictecacíhuatl: life is full of joy, passion, trials, and tribulations and it still goes on. The only constant in life is death.

As Catrina continues to dance and dance without ceasing in Caraza’s work, she reminds us to enjoy the sweetness of life. As the Mexican Revolution changed the political and social circumstances in the lives of so many Mexican people, so has Catrina changed the people’s attitudes towards toward death from the rigid sobriety of the Aztecs to one of humor, laughing at the inevitable.

Comments: