Content

This unit is created to help students develop an authentic understanding of the basic number system through applicable hands-on activities and content relevancy. It is crucial that they construct meaning for themselves using engaging teaching strategies. This understanding, needs to begin with repeated and prolonged exposure to the base ten system and place value It is designed to enhance or present an in-depth understanding of basic number relations for my 6th grade math class. It is also designed using English as a Second Language (or ELL) strategies, and emphasizes relevant content to support the understanding of the foundational math concepts. The unit addresses place value, procedural computation, decimals and estimation. Here are more details about the topics involved:

- Place Value – whole numbers, place value, and decimals to the hundredth. To develop further understanding of place value concepts, my activities will involve concrete models (place value mats, place value chart, and number lines), and practice using place value language orally; and illustrations; and will develop connections to real world situations with numbers at school, home, and community to make learning meaningful.

- Procedural computation of addition and subtraction – using the strategy for adding and subtracting using expanded base 10 form.

- Decimal fractions – Using place value and number lines to support student’s conceptual understanding of decimal fractions.

- Connecting Decimals to money – Using real world context to help students understand the concept of money.

- Estimation and basic error in connection to the concept of money –Using real world situations with money, students will have a better understanding of the amount of error when rounding to the nearest whole number and to the nearest tenth.

Place Value

Place value is an important foundational concept in the development of math skills. It is essential to have a strong foundation in place value in order to achieve success in making sense of the number system for counting, adding-subtracting-multiplying-dividing multi-digit numbers, estimating, decimals, and other mathematical skills. Place value is a key concept for students to learn and have a better understanding of numbers greater than ten. For this reason, it is important to teach it, in isolation at first, but also reviewing and integrating it into other concepts throughout the year. I believe helping my students build understanding of place value through base-ten and interesting problems, will help them through their mathematical journey. Recognizing that numbers can be broken apart, rearranged, and re-grouped, gives students a better understanding of how addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division work. This is especially true when my students have a sound understanding of what each part of a whole number represents

An introductory review of place value will use modeling of hundreds, tens, ones on a place value mat using base 10 blocks, using these simple tools to develop conceptual understanding. I call it a review, since this method is usually taught at the elementary level.

- Review a one-digit number with the student. Write the number and place the corresponding number of units on a place-value mat. For example, the number 7 has 7 units blocks in the ones place. We use little blocks, called units or unit cubes, to show the number of ones. The number 7 does not have any tens or any hundreds, so we leave those columns empty: 7 = 7 ones.

- Review the number 10. Write the number 10. Place 10 units in the ones column. Line them up to show 10 units to equal 1 rod. Exchange the 10 ones (unit blocks) for 1 ten (rod) and place the rod in the tens column.

- Point to the 1 in the tens place of the written number (10) and the 1 rod in the tens column on the place-value mat. Emphasize that 0 in the ones place of a written number corresponds to an empty ones column on the place-value mat. It represents 1 ten and zero ones.

- Explain the same details for the number (100) which is represented by what we call a flat or 10 rods put together to produce a 10x10 square. Discuss larger number representation, simultaneously show visuals of the object on the promethean board to aid in their understanding. Emphasize that one hundred equals ten tens.

- Write a three-digit number such as 142. Review that this means one hundred plus four tens plus two ones. Place two unit blocks, four rods, and one flat in their corresponding columns. Explain that the two units equal the number of ones in the number 2, the four rods equal the number of tens in the number 40, and the one flat equals the number of hundreds in the number 100. Draw a connection between the numbers of objects in each column of the place-value mat with the corresponding digits in the written number. The whole number is the sum of these pieces. In symbols, 142 = 100 + 40 + 2. Continue the lesson by discussing how other numbers are represented and have students use the place value mat to demonstrate understanding.

Then have students use a place value chart to illustrate the corresponding value of the digit. Using the chart emphasizes the value of a digit to the left of another digit is 10 times larger and the value of the digit to the right of that same digit is one tenth the value. For example, if we have the number 432, which is said “four hundred thirty-two”, the 4 means 4 hundreds, the 3 means 3 tens, and the 2 means 2 ones. In symbols,

432 = 4´100 + 3´10 + 2 ´1 = 4´(10´10) + 3´10 + 2 ´1.

Place value is one of the key concepts in a mathematical curriculum and though it is only explicitly taught in the lower grades, understanding place value (or not understanding it) will follow students through their mathematics journey. It is essential that students understand the meaning of a number. For example, in the number 635, the 6 represents 600. Without this understanding, students often struggle with when to “borrow,” or regroup. This hinders their understanding of algorithms for adding and subtracting multi-digit numbers.

(The place value chart is an instructional tool to support students' understanding of the number system.)

Using a number line is another useful strategy in strengthening my students' number sense. The use of a number line not only helps students use a tool to solve math situations, but also helps my students develop the necessary number sense to construct mathematical meaning and numerical relationships. The number line is an effective teaching tool that can be integrated in many math lessons as a visual aid in strengthening my students' understanding of mathematical concepts.

Number Lines can be used in conjunction with Place Value charts, which are both effective teaching tools. The place value number system is built around ten symbols which we call digits (0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9). Using combinations of these digits, we can create an numbers as large or as small as we want. The value of a digit depends on its place, or position, in the number. Each place has a value of 10 times the place to its right and one tenth times its value to the left. A number in standard form is separated into groups of three digits using commas, to make it easier to read. Each of these groups is called a period. A number in standard form is understood to be the sum of the numbers represented by the individual digits, which gets ten times larger for each place from the right. For example, 435, is 400 + 30 + 5. Another example: 6,802 is the sum of 6,000 + 800 + 2. Notice there is a zero for the tens place, so the tens place has no value. The 6,802 is considered standard form which is the sum of 6,000 + 800 + 2 in expanded form. The 6 is in the thousands place, and represents 6 thousands. The 8 is in the tens place, and represents 8 hundreds. The 0 is a place holder for the tens place, and represents zero tens. The 2 is in the ones place, and represents 2 ones. Once this fundamental concept is understood, we will give the pieces represented by the digits a name: place value pieces. (a single digit times a product of some 10s, also called a power of 10). This gives us five increasingly explicit ways to write a base ten number. We call these the five stages of place value.(Howe-Reiter). (1)

For example using the standard representation of 4,769:

The five Stages of Place Value

4,769 (standard form)

= 4,000 + 700 + 60 + 9 (2nd stage)

= 4 × 1,000 + 7 × 100 + 6 × 10 + 9 × 1 (3rd stage)

= 4 × (10×10×10) + 7×(10×10) + 6 × 10 + 9 × 1 (4th stage)

= 4×103 + 7×102 + 6×101 + 9 × 100 (polynomial in 10)

In the five stages of place value the second stage is explained as an expanded form of the standard number. It shows that the number is the sum of its place value pieces. The 3rd stage shows the same quantity but using the one digit multiplied by the base 10 units such as 4 x 1,000, 7 x 100, 6 x 10 and 9 x 1. It shows that each place value piece consists of the given digit times a base ten unit (1, 10, 100, etc.). The 4th stage shows that each base ten unit is a product of tens, with one more ten for each place to the left of 1: 1,000 = 10×100 = 10×(10×10), which is the same as 1,000 = 10×10×10. Similarly, 100 = 10 x 10. This concept is usually not taught in our elementary school, but it is an important step. It shows the relative values of the base ten units whereas each base 10 unit is 10 times larger than the one to the right, and only one tenth as large as the one to the left. So, using this concept you can see that it doesn't take very many digits before the numbers are very large or very small, when multiplying by 10. The last stage is the polynomial in 10, which deals with the order of magnitude. The order of magnitude of a single-place number is the number of zeroes used to write it, for instance using the standard number above would be 4,000 = 4×103, 700 = 7×102, 60 = 6×101 and 9 = 9×100. The order of magnitude is also the number of 10s multiplied together to make the base ten unit, and it appears as the exponent in the polynomial form. Hence, the order of magnitude of 4,000 is 3, the order of magnitude of 700 is 2, the order of magnitude of 60 is 1 and the order of magnitude of 9 is 0. The first four stages are important for concepts for my students to comprehend so they have a better understanding of the computational components of adding and subtracting. We will not worry about the 5th stage, which involves concepts from later grades. In our 6th grade Common Core Standards, students are expected to fluently add and subtract multi-digit numbers, but some of my students still struggle with two-digit adding and subtracting, so I believe these stages will enlighten their understanding of numbers to support these two math concepts.

I find that using number lines helps my students build their mental math ability in creating models to defend their thinking, and to explore relationships between numbers and operations. As students use the number line they can visually see that there are many different ways in reaching the same number, but there is also an efficient strategy, which is the expanded form. In instructing place value I will use hands on materials such as base 10 blocks and number lines, which are effective, but I will also make sure to simultaneously connect these to the symbolic forms of the stages of place value.

The following is a collection of examples of the kinds I will use with my students. My goal is to help them see how the usual procedures for addition and subtraction are based on the expanded form of numbers.

Addition

The addition algorithm is a strategy for adding two numbers in base 10 form. It consists of three steps:

1. Break each of the numbers (the “addends”) into its single-place components.

2. Add the corresponding components for each order of magnitude. If the component for an order of magnitude of an addend is missing, it is treated as if it were zero.

3. Recombine the sums from step 2 into a number in base 10 form.

Here is an example procedural computation of addition:

345+621 = (300+40+5)+(600+20+1) by breaking each addend into its single-place components

= (300+600)+(40+20)+(5+1) by grouping single-place components by order of magnitude

= 900+60+6 by adding components for each order of magnitude

= 966 by recombining the single-place components into a base 10 number.

Sometimes step 3 entails regrouping:

437+254 = (400 + 30 + 7) + (200 + 50 + 4)breaking each addend into its single place component

= (400 + 200) + (30 + 50) + (7 + 4) group the single-place components by order of magnitude

= (600 + 80 + 11) adding components for each order of magnitude we see that we have 11 in the ones place so we need to regroup to move the 10

= (600 + 80 + 10 + 1) from the ones (10 + 1) which leaves 1 in the ones place and add one 10 to the tens place to make it

= (600 + 90 + 1) (80 + 10 = 90), or 9 tens.

= 691

Subtraction

Vocabulary for the subtraction concept:

15 - 10 = 5

Minuend − Subtrahend = Difference

Minuend: The number that is to be subtracted from.

Subtrahend: The number that is to be subtracted.

Difference: The result of subtracting one number from another.

Subtracting a number undoes adding a number, taught as fact family in the elementary grades. This supports the students' understanding that if, a – b = c then b + c = a, or using digits as an example is 15 - 10 = 5 then 10 + 5 = 15

When the subtraction a − b = c involves no regrouping or borrowing then the same orders of magnitude are affected in both computations. For example,

5631 - 3,221 = (5,000 + 600 + 30 + 1) - (3,000 + 200 + 20 + 1)

= (5,000 – 3,000) + (600 - 200) + (30 - 20) + (1 - 1)

= 2,000 + 400 + 10 + 0 = 2,410

Sometimes, however, there are not enough of some unit in the minuend to subtract the corresponding part of the subtrahend. In this case, one copy of a larger unit must be broken up to provide 10 extra copies of the deficient unit. This process is called regrouping.

For instance, in this example one 1,000 must be regrouped into ten 100s:

5431 - 3,721 = (5,000 + 400 + 30 + 1) - (3,000 + 700 + 20 + 1)

= (5,000 – 3,000) + (400 - 700) + (30 - 20) + (1 - 1)

Starting with the ones place we see this can be subtracted (1 – 1 = 0), then the tens place we can subtract (30 – 20 = 10), but when we get to the hundreds place the subtrahend is larger than the minuend, so we need to regroup or borrow from the thousands place. When we borrow the 5,000 becomes 4,000. The 1,000 that is borrowed is added to the hundreds place making it 1,400. Now we can complete the computation.

= (4,000 – 3,000) + (1,400 – 700) + (30 – 20) + (1 – 1)

= 1,000 + 700 + 10 + 0

= 1,710

Regrouping may be required for multiple base ten units. This next example involves three places of regrouping:

6,453 – 3,784 = (6,000 + 400 + 50 + 3) - (3,000 + 700 + 80 + 4)

= (6,000 – 3,000) + (400 – 700) + (50 – 80) + (3 – 4)

= (6,000 – 3,000) + (400 – 700) + (40 – 80) + (13 – 4)

= (6,000 – 3,000) + (300 – 700) + (140 – 80) + (13 – 4)

= (5,000 – 3,000) + (1300 – 700) + (140 – 80) + (13 – 4)

In this problem we start with the ones and see the subtrahend is larger than the minuend, so we need to regroup or borrow from the tens which adds 10 to the 3 in the ones place and now we can subtract (13 – 4 = 9). Since we borrowed from the tens the subtrahend for the tens is reduced to 40, so we regroup or borrow from the hundreds which adds 100 to make it 140 and now we can subtract (140 – 80 = 60). Next, since we borrowed again from the hundreds the subtrahend is reduced to 300, and we borrow from the thousands place which increases the subtrahend to 1,300 and we are able to subtract (1,300 – 700 = 600). Now we can continue to solve the problem:

= (5,000 – 3,000) + (1,300 – 700) + (140 – 80) + (13 – 4)

= 2,000 + 600 + 60 + 9 = 2, 669

Unfortunately for learners of subtraction, even understanding how to do multiple regroupings as above is not enough to solve all subtraction problems. In fact, unlike addition, there are not a fixed number of procedures that allow solving all subtraction problems. The most difficult part of subtraction for students is what is called “borrowing past a zero”. This can actually involve borrowing past arbitrarily many zeros. The basic problem can be seen when subtracting two place value pieces. For example, consider the following problems

70 – 3 = 60 + (10 – 3) = 60 + 7 = 67

700 – 3 = 600 + 100 – 3 = 600 + 90 + (10 – 3) = 600 + 90 +7 = 697

7,000 – 3 = 6,000 + 1,000 – 3 = 6,000 + 900 + 100 – 3

= 6,000 + 900 + 90 + (10 – 3) = 6,00 + 900 + 90 + 7 = 6,997

It can be necessary to decompose arbitrarily many base ten units to enable to perform subtraction at a single place. When a problem like this is embedded in a more complicated situation, students can find it confusing. I will try to help them understand subtraction better by having them work numerous examples with both minuend and subtrahend being place value pieces, to help them see the pattern as in the examples above. Then we will work on what to do when this situation appears inside a more general subtraction situation. The good news is, that if you have to borrow across one or more zeros, all the places in the minuend that were zeros become nines, so there will be no need to borrow at those places.

Decimals

Sets of numbers, like whole numbers and decimals, are all important concepts that my students need to learn, and I believe it's easier for them to decipher when used in conjunction with place value chart and number lines. With decimals, it is important for my students to understand whether a number or digit is in the ones or tenths place. Conventionally, I use the standard practice of writing a decimal point (period) to the right of the ones, in between the ones and tenths place. One good strategy is to place these on a number line, so students see, as with whole numbers, the value of any digit is divided by 10 if it moves right one place. When 4 tenths is written as 0.4, the zero shows there are no ones, the point indicates that the whole numbers have ended, and the 4 means 4 tenths. It’s important that my students understand place value with decimals: 0.4 is not to be said as “zero point four”, but rather as “zero ones and four tenths” so that students will recall such knowledge and be able to understand decimal values as well as whole number values. Decimal Number lines will be used in order to display a variety of numbers that can be incorporated in accordance with the Curriculum using the Common Core Standards. If this area is neglected, not understood or not taught properly, it may hinder the ability of my students to master later mathematical concepts. Visual models, including number lines, would aid in the understanding of decimals and a simplified way of showing their relationships, and especially, that for each place you move to the right, the value of the digit gets divided by 10. One task would entail students to break down decimal places into tenths, hundredths, thousandths and so on, to show how the digits actually look. Another strategy I plan to use for a visual model is using place value in accordance with a number line to show that 9 tenths are greater than 7 tenths, and also that .9 > .72 > .651 and so on. They will be able to grasp this concept through using visual example models. I know that there are some common misconceptions that have been documented that can occur when teaching Place Value. For this reason, I want to make sure I am teaching the students correctly, so my students are able to use this concept of decimals and move on to the next concepts of comparing decimals and rounding. So, my next mini lessons will be comparing and ordering decimals and how to round decimals to the nearest hundreds, tens, tenths, and hundredths. These concepts are also important for my students to comprehend numbers both whole numbers and decimal numbers.

Connecting Decimals to Money

Procedural fluency is defined by the Common Core as “Skill in carrying out procedures flexibly, accurately, efficiently and appropriately.” In 4th and 5th grades, students are supposed to add and subtract decimals. In 6th grade, students are expected to become fluent in the use of the standard algorithms of each of these operations, but my students still needed the basic understanding which I covered in the previous lessons. In fact, these algorithms are exactly the same as for whole numbers if you think in terms of base ten units and the relationship between two adjacent units. I will work hard to get my students to understand this idea.

The previous lessons, and especially understanding the size relationship between places, should help them understand the next mathematical concept of estimation. The use of estimation strategies should support my students understanding of decimal operations. Therefore, learning decimals is another important concept in understanding numbers. Since my students have already learned about whole numbers in the previous lessons I would like to introduce or review depending on my students’ understanding, the same stages to teach about decimals. After my students have better understanding of whole numbers and decimal numbers they will be ready for the next lesson of connecting these two concepts into money, a very real-world topic that they need to understand. With this lesson I will use money as a connection to understanding decimal values and also connect Navajo language (speaking and writing of money) into the lesson. The reason I am using money for the relevancy connection is due to the fact that my students are naïve about it. Most of my students have not been exposed to budgeting and the value of money. I want them to understand that “money does not grow on trees”, as the saying goes. Also, budgeting is a life skill that is important for our students to learn for their future.

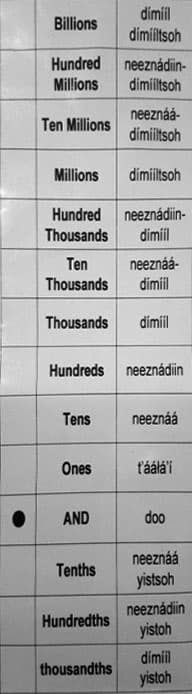

So, when I start this lesson the students will practice writing decimal numbers in expanded form, standard form, and word form using English. Next, they will use the word form concept as a guide in understanding how to translate the English language into the Navajo language. I will introduce the Navajo words orally while the students have the written form (I will have the Navajo words listed on a sheet as a guide), and I will have students learn how to say the words by repeating after me. We will practice by using cooperative learning styles in partners or groups to sound out words. Then I will start having them write the words using the sheet as a guide, next they will continue to practice by using the worksheet shown below. In my opinion our Native American students are motivated to learn when their Navajo language and culture are part of the learning process.

Money Language: Write the money in English and translate into Navajo.

1) $ 52.01 - English ___________________________________________________________

Navajo __________________________________________________________

2) $ 47.84 - English__________________________________________________________

Navajo___________________________________________________________

Once my students have a better understanding of place value, procedural computation of addition and subtraction, and decimals, our next step is to learn estimation, using money. Students will learn estimation and connect this concept using real world situations such as estimating the cost of a grocery bill or budgeting.

Estimation

First, students need to know estimation words and phrases, such as “about”, “close”, “just about”, “a little more or less than” and “between these two numbers. I will try to make these ideas meaningful for my students by having them plot some numbers and their rounded versions on number lines of a suitable size. Students should understand that they are trying to get as close as possible using quick and easy methods, but there is no actual correct estimate. An estimate depends on how close you want to get to the actual number, which connects to the concept of error.

By itself, the term “estimate” refers to a number that approximates an exact number given in a particular context. This concept of an estimate is applied not only to computation but also to other math concepts such as measures and quantities. For this unit we will discuss estimates for money.

Whenever we are faced with a computation in real-life, we have a variety of choices to make concerning how we will handle the computation. Do we need an exact answer, or will an approximate answer suffice? Sometimes, we do not need an exact answer and so we can use an estimate in real world context. Next, we need to know how close an estimate do we need? This also depends on the situation, which connects to error. Error in this unit context is the magnitude of the difference between the exact value and the approximation to the whole number or to the dime, which is called the “absolute error”. The following are three strategies that can be used in estimating money. Front-end method is a strategy that focuses on the leading or left most digits in numbers or whole (dollar amount) number and ignoring the cents. After an estimate is made on the basis of only these front-end digits, an adjustment can be made by noticing how much has been ignored. Usually the error is larger using this method in the context of money. One strategy to instruct this concept is to give them a list of numbers, of many different sizes (including some decimal fractions) and have them compare the value of the leading digit with the rest of the number. Is it always bigger than the rest of the number? How often is it twice as big? Five times as big? Ten times? Then repeat the same question with the same numbers, but ask them to compare the value of the leading two digits with the rest of the number. Is it always10 times as big? How often is it 20 times as big? Fifty times? One hundred times? Then repeat everything with amounts of money. It doesn’t need to lead to anything formal, but if you discuss it and ask what they learned from it, hopefully some students will say that the first digit is the most important, more than all the rest, and the first two digits tell you almost all (in fact, at least 90%, but that level of precision is not crucial) of the number.

Rounding methods is the familiar form of estimation and is a way of changing the problem to one that is easier to work. We can round to the nearest dime, dollar, ten dollars, hundred dollars and so on. Good estimators follow their mental computation with and adjustment to compensate for the rounding. When adding a long list of numbers, it is sometimes useful to use compatible numbers – that is, to look for two or three numbers that can be grouped to make benchmarks of 10, 100, 1,000 and so on.

I believe the best instructional approach to improve my students' estimation skills is to have them do a lot of estimating using the three methods. Finding real life estimating problems and discuss the strategies we need to use in which the computational estimations will suffice. Some simple examples include dealing with grocery store situations, adding up distances in planning a trip, determining approximate yearly or monthly totals of household bills and figuring the cost of an evening out. Discuss why exact answers are not necessary in some instances and why they are necessary in others. Using real life context to help with understanding estimates is a good strategy to help students understand that math is a part of our daily life. For instance ask students, “Would the cost of a car more likely be $950 or $9500?” Also ask, would the cost of a car more likely be $1,000 or $10,000, and then ask if there is a very big difference between these two questions. A simple computation can provide the important digits. An estimate is usually only about the first, or maybe the first two digits. Of course, there is no correct answer but a range of answers. I intend to focus on flexible methods of estimation. My primary concern is to help students develop strategies for making estimates. Reflection on strategy use will lead to strategy development and understanding of estimating in a real-life context. It's also good to discuss how different students made their estimates. This helps students understand that there is no single right way to estimate and reminds them of different approaches. If estimates differ in the first digit, it is important to figure out why. Maybe the true number was almost halfway in between two place value pieces. If estimates differ in the second digit, that is pretty normal, and not as important. Reiterate to students that estimates are not the exact answer but an educated guess using the understanding of numbers and error. Think in relative terms about what is a good estimate.

Mathematically, at this point, my students should have a better understanding of place value, whole numbers (addition, subtraction), and decimals. So, before I begin estimation with my students I will complete an informal pre-test by arranging approximately 10 items with their prices marked on a table in the classroom. I will give the class a minute or two to determine the total cost of the 10 items. The students should not write down anything while they are looking at the items. Next, I will ask the students to record their estimate of the price of the ten items on a sheet of paper. Also, I will ask them to briefly write down any impressions they had while making their guesses. We will debrief together and discuss their answers. This strategy will expose them to different methods of estimating, and by discussing their outcomes, they can comprehend that estimation is a flexible concept depending on the situation.

Students will use estimation in a real-life context using the concept of money.

Ex: Carrots cost $2.71, peppers cost $1.73 and broccoli cost $1.10. estimate the total cost of the vegetables but rounding to the nearest whole dollar and to the nearest dime

(have them underline each dollar and circle each tenths place to round to the nearest whole number or dollar, next have them underline the tenths place (dime) and circle the ones place (penny) which is rounding to the nearest dime.)

|

Dollar |

Dime |

|

$2.71 ~ 3.00 |

$2.71 ~ 2.70 |

|

$1.73 ~ $2.00 |

$1.73 ~ $1.70 |

|

$1.10 ~ $1.00 |

$1.10 ~ $1.10 |

|

Estimated cost of the vegetables is $6.00 (error = $0.46) |

Estimated cost of the vegetables is $5.50 (error = $0.04) |

The main reason I want to incorporate a lesson on money is because many of our students and their family sell goods as their sole source of income. Students as young as 7 years old are selling jewelry in restaurants, outside of businesses, and at swap meets. This is also a real world connection for our students. When the concept is relevant to them they tend to have a better understanding.

Comments: