Background

Bacteria

Bacteria were among the oldest life forms on Earth. Fossil evidence suggests that they appeared more than 3 billion years before plants and animals did.4 These microscopic, single-celled organisms are ubiquitous and can survive in any climate. They are found in volcanic vents deep below the ocean, in glacial ice, in air, and on the surface and the insides of plants, animals, and humans. Bacterial cells are prokaryotic, meaning that they lack a well-defined nucleus and membrane-enclosed organelles.

Bacterial Cell Structure

The bacterial cytoplasm contains the chromosome and ribosomes, and may also contain plasmids (accessory miniature chromosomes). For most bacteria, the chromosome is composed of a single circular strand of DNA. Like a eukaryotic cell, a bacterial cell contains ribosomes that translate genetic information into amino acid sequences that make up proteins. Bacterial ribosomes, however, differ in structure to eukaryotic ribosomes. This distinction is important for it allows some antibiotics to attack the bacterial ribosomes without harming the host (eukaryotic) cells.

The plasmids are small loops of genetic material. Like the chromosome, plasmids may contain genetic information for the production of disease-causing molecules, called virulence factors. These molecules allow pathogenic bacteria to: (1) gain entry into their host, (2) cause disease, and (3) avoid detection by the host’s immune defenses.5 Unlike the chromosome, plasmids are mobile genetic elements that can be transferred from one cell to another in a process known as conjugation. Through this horizontal gene transfer, plasmids spread advantageous mutations, including antibiotic resistance, from cell to cell.

A 2- or 3-layered cell envelope that is made of an interior cytoplasmic membrane, a cell wall, and in some bacteria, an exterior capsule, protects the bacterial cytoplasm. The inner cytoplasmic membrane is made of a layer of phospholipids and proteins that controls the movement of materials in and out of the cell. The exterior capsule, which is made of polysaccharides, prevents the cell from drying out and protects it from being engulfed by phagocytic cells of the human immune system. In some bacteria, the capsule contains major virulence factors. The cell wall is a strong mesh-like structure that gives the bacterium its shape and keeps it from bursting when it becomes engorged with water. It is made of a polymer, called as peptidoglycan. The thickness of the peptidoglycan layers differentiates the bacteria into two classes: gram-positive and gram-negative. This classification is based on the cell wall’s ability to retain the blue and red dyes used in the Gram test. Gram-positive bacteria have thick layers of peptidoglycans and can retain both blue and red dyes. Gram-negative bacteria, which only stain red, have a more complex cell wall structure - an inner thin peptidoglycan layer, and an outer membrane composed of two layers, one made of phospholipids, and another of lipopolysaccharide. The outer membrane has tiny pores that allow tiny molecules, like nutrients, to enter but not large molecules, like antibiotics. The almost impermeable cell wall of the gram-negative bacteria makes them more resistant to antibodies and antibiotics.

The Importance of Bacteria

Undoubtedly, bacterial infections have claimed countless lives but it is important to note that only a small number of bacterial species are disease causing. Most bacteria are not only harmless, but are even critical to our survival. Researchers of the Human Microbiome Project, found that there are more bacterial genes that contribute to human survival than there are human genes.6 Bacteria in the gut, for example, provide enzymes that humans make in insufficient amounts, to break down carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins as nutrients that the body can absorb and use. Also, bacteria can protect us from diseases by breaking down toxic chemicals, by producing vitamins and anti-inflammatory agents, and by crowding out pathogenic strains. There is now mounting evidence that bacteria also produce other chemicals that help shape our gut, our immune system, and even our nervous system.7

Bacteria also play a critical ecological role. They recycle vital nutrients that other living organisms need to survive. Carbon trapped in dead plants and animals would be unavailable to photosynthetic organisms without decomposing bacteria that break down their tissues and release carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria convert atmospheric nitrogen into nitrate and nitrite, forms of nitrogen that plants can readily absorb from the soil and transform into proteins. Denitrifying bacteria complete the cycle by converting the nitrate and nitrite back into nitrogen and nitrous oxide. Just as in the carbon and nitrogen cycles, bacterial processes help transform sulfur into its various forms. Sulfur-oxidizing bacteria transform hydrogen sulfide to sulfur, and then to sulfate ions, which are absorbed and assimilated into plant and animal tissues. When plants and animals die, the sulfate-reducing bacteria complete the cycle by converting the sulfate back into hydrogen sulfide. The nutrient cycles of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur will certainly grind to a halt without the help of bacteria.

Antibiotics: Our Chemical Weapon

To use the term antibiotic precisely, it is important to clarify its meaning and distinguish it from related words such as antibacterial, antiseptic, and disinfectant. Antibiotics refer to a general term for chemical compounds used to kill or inhibit the growth of certain microbes, especially bacteria and fungi. Antibacterial, as the term implies, is a more specific term for chemical compounds that act only on bacteria. Non-scientists, however, are more familiar with the term antibiotics and use it frequently when referring to antibacterials. Today, even scientists use the two terms interchangeably.8 Antibiotics, antiseptics, and disinfectants are all harmful to bacteria, but they differ in their effects on humans. Antibiotics are called “magic bullets” because they are harmful to bacteria but have little or no adverse effects on humans. Antiseptics are harmful to humans when taken internally but can be safely applied externally. Triclosan is a common example of antiseptic used in soaps, shampoo, and cosmetic products. Disinfectants are chemicals that are harmful when applied to the skin but can be safely used to clean surfaces. Common examples include bleach and formaldehyde. Antiseptics and disinfectants stop infectious microbes from spreading, while antibacterials or antibiotics prevent or cure infections.

Antibiotics’ Mode of Action

Different classes of antibiotics have different modes of action. Antibiotics can either kill (bactericidal) or inhibit growth and reproduction (bacteriostatic). Antibiotics do these tasks through different mechanisms. Sulfa drugs, like sulfanilamide, harm the bacterium by inactivating the enzyme it needs to make folic acid, a vital growth nutrient. Some antibiotics work by inhibiting cell wall synthesis. Classes of antibiotics that use this mechanism include the β-lactams, like penicillin, and glycopeptides, like vancomycin. Other antibiotics like the lipopeptides disrupt the normal function of the cell wall. Antibiotics can also destroy the bacteria by inhibiting the synthesis of proteins. Many classes of antibiotics work in this fashion including the aminoglycosides, streptogramins, oxazolidinones, tetracyclines and macrolides. Quinolones and ansamycins use the last mode of action, the inhibition of RNA synthesis or DNA replication and transcription.

Optimal Antibiotic Treatment Strategies

Different classes of antibiotics differ in their dose level, dosing frequency and duration, route of administration, and bacterial target. This means that a huge number of possible treatment strategies must be tested in order to determine the most effective regimen for each antibiotic-bacterial pair. Without an effective model for predicting and testing optimal antibiotic treatment regimens, this process can be painstakingly slow and expensive. Fortunately, some scientists are working hard to develop such models. A team of scientists recently reported a mathematical model based on the chemical kinetics of the antibiotic-target binding process.9 Using the half-life of the antibiotic-target complex and the rate of the drug’s transmembrane diffusion, they were able to create time-antibiotic concentration profiles that allow for the rapid and rational design of optimal treatment strategies.

Antibiotic Resistance: The Enemy Fights Back

As early as 1945, the year Alexander Fleming received a Nobel Prize for his serendipitous discovery of penicillin, he already sounded the alarm about antibiotic resistance due to inappropriate use.10 Just ten years after penicillin was first used in 1940, resistant strains of bacteria were already prevalent. Since then, whenever a new class of antibiotics is introduced, resistance appears soon after. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), for example, appeared within a year of the introduction of methicillin.11 Currently, various species of hard-to-treat multi-drug resistant bacteria have emerged. The fact that bacteria can develop resistance so quickly should not come as a surprise. For one, bacterial reproduction is incredibly fast; their numbers can double within 4 to 20 minutes under ideal growth conditions containing abundant resources. Second, resistant bacteria can also horizontally transfer their resistance genes to other bacteria through plasmids. Third, some species of bacteria have a natural resistance because they themselves produce antibiotics that they use to kill competing bacterial species.

Modes of Antibiotic Resistance

Pathogenic bacteria resist antibiotics through several highly effective counterattack strategies. The first strategy could be called the “antiballistic missile approach” where the bacteria destroy the antibiotic before it hits its target.12 They do this by producing proteins that change and inactivate the antibiotic. The second strategy is based on the idea that an antibiotic has to reach a threshold concentration in order to work. To keep the antibiotic from reaching this concentration, some bacteria have evolved protein pumps inserted in their cytoplasmic membranes. These pumps actively “spit out” the antibiotics that manage to enter the cell, so its concentration always remains too low to do much damage. This strategy works for antibiotics that must cross the cytoplasmic membrane to attack the ribosomes responsible for protein synthesis. The third strategy is the most daring and potentially lethal to the bacterium. It renders the antibiotic useless by modifying some of its own parts. If the antibiotic targets its enzyme, then bacteria with mutations that modify this enzyme can be favored; if the antibiotic targets its ribosomes, then mutational changes to parts of the ribosomes may prevent the antibiotic from binding. While effective, this evolved strategy could be costly to the bacterium, because in the process of mutationally changing, these various components could stop functioning properly.

Enzymes

Enzymes are proteins that act as biological catalysts. They speed up biochemical reactions by binding with the reactants (substrates), changing their configuration, and taking them through a reaction pathway of lower activation energy. The catalytic action of an enzyme is highly specific; that is, only a certain substrate or group of substrates can bind with a particular enzyme. This is so because the enzyme’s active site has a specific geometric shape, determined by the structure of its amino acids that allows only a substrate with the correct size and shape to fit into and bind with it. The enzyme interacts with a substrate through electrostatic forces that change the distribution of charges in the chemical bonds of the substrate. This leads to the transformation of the substrate into a new substance. Once formed, the new substance separates from the enzyme so the enzyme is free to bind with another substrate molecule.

Two theories have been put forward to explain the specificity of the enzyme-substrate interaction. The lock-and-key theory treats the enzyme as the lock and the substrate as the key. In the same way that only a specific key can fit into a lock, only a substrate with the right shape and size can fit into the rigid shape of the enzyme’s active site. The induced fit theory was proposed to explain the fact that in some cases, different substrates can find their way into the active site. According to this theory, enzymes are somewhat flexible, and their structure can be influenced by the substrate. If a substrate can induce the enzyme to change its shape, then proper orientation and binding can occur.

Role of Enzymes in Antibiotics Design and Development of Bacterial Resistance

Enzymes play a central role in the chemical warfare between humans and pathogenic bacteria. Most antibiotics are designed to target specific enzymes critical to bacterial growth and reproduction. Enzymes are ideal drug targets because molecules can be designed to complement the structure of the active site.13 The β-lactam group of antibiotics for example, specifically targets and inactivates the enzyme needed for the synthesis of the bacterial cell wall. β-lactams, which include penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, and monobactams contain a four-membered nitrogen-containing ring that is responsible for their antibiotic activity.

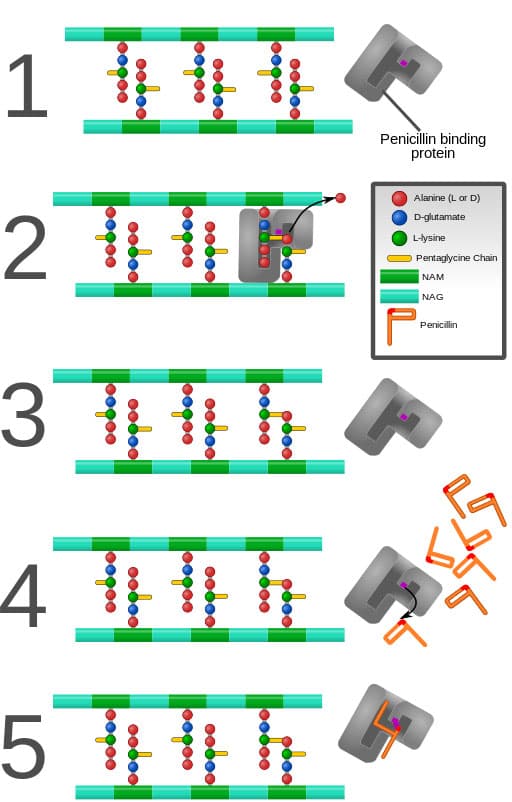

Penicillin’s specific mode of action is illustrated in Figure 1 below. Part 1 of the diagram shows the peptidoglycan strands that eventually form the mesh-like structure of the bacterial cell wall. The strands are made of alternating sugar subunits, N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) and N-acetylmuramic acid (NAM). Attached to these strands are peptide chains made of three to five amino acids. Part 2 of the diagram depicts how the penicillin-binding protein binds with the peptide chains, catalyzing the cross-linking of the peptidoglycan strands. Part 3 shows the enzyme dissociating from the cross-linked strands. Parts 4 and 5 illustrate how penicillin prevents the cross-linking process by permanently binding with the enzyme’s active site. Because the penicillin is permanently bonded to the enzyme and therefore cannot be regenerated, it is called a suicide inhibitor.

Figure 1. Inhibition of the Penicillin-Binding Protein. Source: Mcstrother, CC BY 3.0, 2011. Available from Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Penicillin_inhibition.svg

(accessed July 14, 2018)

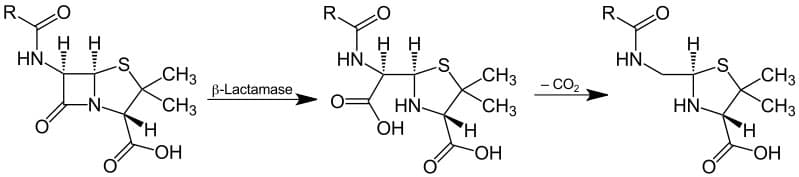

In response to the lethal action of β-lactams, various bacterial species have evolved and developed a resistance by producing a group of enzymes, the β-lactamases that inactivate the antibiotics. As Figure 2 below shows, the β-lactamases catalyze the hydrolysis of the 4-membered β-lactam ring that is responsible for the drugs’ antibacterial action.

Figure 2. Mechanism for β-Lactamase Action. Source: Jü [Public domain]. Available from Wikimedia Commons: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/ca/Lactamase_Application_V.1.svg

(accessed July 14, 2018)

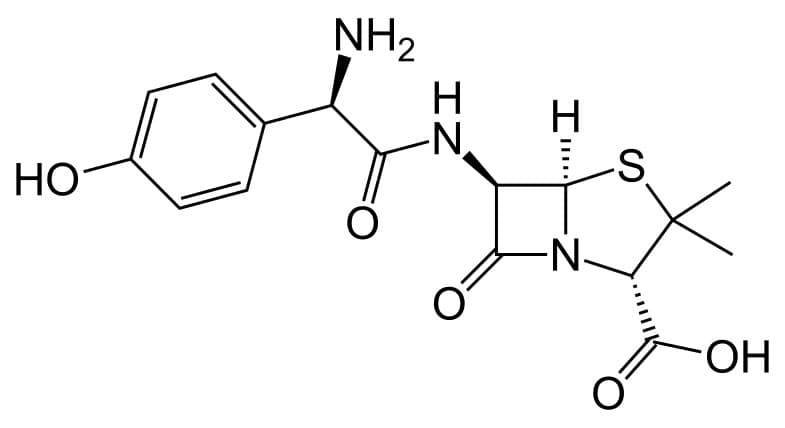

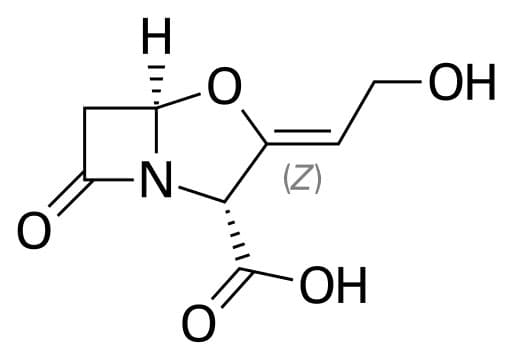

To inhibit the β-lactamases from destroying the antibiotics, drug formulations that combine structurally-similar β-lactams have been used. Augmentin, a combination of two active ingredients, amoxicillin and clavulanic acid, is an example. As shown in Figures 3 and 4 below, clavulanic acid is structurally similar to amoxicillin, so the bacterial β-lactamases are tricked to bind with it, leaving the amoxicillin to do its lethal task. Predictably, bacteria with modified β-lactamases have evolved. Clavulanic acid is once again rendered ineffective, as it is now unable to bind with the bacterial enzymes.

Figure 3. Structural Formula of Amoxicillin. Source: Fvasconcellos (talk · contribs) [Public domain]. Available from Wikimedia Commons: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/02/Amoxicillin.svg (accessed July 14, 2018)

Figure 4. Structural Formula of Clavulanic Acid. Source: Fvasconcellos (talk · contribs) [Public domain]. Available from Wikimedia Commons: https://upload.wikimedia.orgn/wikipedia/commons/6/63/Clavulanic_acid.svg (accessed July 14, 2018)

Need for Novel Antibiotics and Alternatives to Antibiotic Therapy

The increasing incidence of multi-drug resistant infections highlights the urgent need to discover antibiotics with novel modes of action. Thankfully, active research in structure-based drug design is happening in many academic laboratories.14 Advances in genomics, proteomics, and bioinformatics are making it easier and faster to identify drug targets. Developments in analytical techniques like nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and x-ray crystallography are facilitating the rapid structure elucidation of these targets. Fast and relatively cheap computers are also making it possible to expeditiously screen a huge number of chemicals for possible drug leads. The rapid identification of targets and drug leads, however, is just a small step in the long and arduous road to a marketable drug product. On average, it takes about 10 years from discovery to clinical testing. This translates to a hefty expense and less profits for pharmaceutical companies. It is no wonder then that in the last 50 years, only two new antibiotic classes have been developed.15

While interest in new antibiotic discovery and development has waned, it is comforting to note that researchers in academic laboratories have not given up. Chemists are still trying to find rapid pathways for synthesizing new antibiotics. Andrew Myers and his team of chemists at Harvard University, for example, are developing a fast and fully synthetic pathway for creating macrolide drug candidates.16 Conventional methods of producing derivatives of the macrolide, erythromycin, involve semi-synthetic modification of the various parts of this huge molecule. These methods can be slow and difficult because erythromycin is a complex molecule with lots of functional groups and varying stereochemistry. To speed up the process, the chemists created small building block molecules, which they then welded together to create new complex molecules. So far they have created about 300 of such molecules.

Some scientists are hoping to prolong the effectiveness of current antibiotics by revisiting old remedies like phage therapy. The use of bacteriophages, or phages for short, in treating bacterial infections predates antibiotic therapy but it has not gained much attention in the US, until now. Phages are viruses that infect and kill bacteria but not human cells. While it has been extensively studied and used in Europe, particularly Poland, Georgia and the Soviet Union, its use in the US has stalled for years.17 The lytic phages attach themselves to the bacteria, inject their genetic material into the bacterial cytoplasm, and use the bacterial processes to make copies of themselves. They create holes in the bacterial cell envelope causing the cell to burst. The new copies of the phage then infect other cells. Unsurprisingly, bacterial resistance to phages has emerged. The development of this resistance, however, can make them vulnerable to antibiotics.18 Thus, phage therapy used in concert with antibiotic therapy, promises to be a potent weapon against antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

The Controversy

Antibiotic Use in Animal Agriculture

In 1950, it was discovered that small doses of antibiotics could make chickens gain weight at a faster rate with less feed.19 It was also observed that larger doses, but below therapeutic amounts, can prevent infections. Both these findings led to the widespread use of antibiotics in animal agriculture. Today, antibiotics are used in animals not just to cure and prevent infections but also to promote growth and improve feed efficiency.20 It is estimated that about 80% of the total amount of antibiotics sold in the US is used for animals.21 The Food and Drug Administration’s 2016 Summary Report shows a total sale of 14 million kilograms.22 This widespread use of antibiotics in food-producing animals is believed to contribute to the emergence and spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Due to concerns over the transfer of antibiotic-resistant bacteria from animals to humans, there is now a growing demand for a ban on antibiotic use in livestock for growth promotion (non-therapeutic) and disease prevention (sub-therapeutic). In early January of 2017, the FDA passed new rules aimed at restricting antibiotic use in animals, but this ban is only for the use of antibiotics for growth promotion.

Cost of Proposed Ban

Modern animal farms are highly efficient. Huge numbers of animals are grown on limited space, using feeds laced with growth-promoting antibiotics. These intensive practices keep production costs low. In 1999, the Panel on Animal Health, Food Safety, and Public Health conducted a study to determine the economic cost of a total ban on sub-therapeutic antibiotics in food animals.23 It estimated a production cost increase of 4 to 20%, which results to an increase in annual per capita cost to consumers of $4.84 to $9.72. Taking into account the population size of 260M at the time the estimate was made, this translates to a total cost of 1.2 to 2.5 billion dollars per year. This estimate does not include the cost due to the loss in US export competitiveness, cost to farmers who are forced out of business, and the decrease in revenues and profits for antibiotic manufacturers. Due to decreased revenues and profits for the animal health industry, another economic cost of the ban could be reduction of funding in antibiotic research and development. To get a sense of this loss, consider that in 1996, the animal health industry invested $381M in new antibiotic research and development.

The close animal contact in high-density farms increases the chances for infections to spread quickly once they emerge. A ban on sub-therapeutic antibiotics will make it difficult, if not impossible, to prevent the emergence and spread of infections. A contagion could have a massive impact on our food supply. Most importantly, it could threaten human health due to the potential for antibiotic-resistant bacteria to transfer from animals to humans.

Benefits of the Ban

In 2016, the World Health Organization assembled a multidisciplinary team of experts to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis in order to determine the effect of reduced antibiotic use in food-producing animals on the presence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in animals and in humans.24 This effort aimed to gather evidence that will inform the formulation of guidelines on the antibiotic use in farm animals. Based on the 94 studies reviewed by the group, it was found that interventions that reduce the use of antibiotic in food-producing animals led to a decrease in the presence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in these animals by 15% and multi-resistant bacteria by 24-32%. A 24% reduction in the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria was also seen in humans, especially among those directly exposed to these animals.

The review also uncovered evidence that antibiotic-resistant bacteria can transfer from livestock to farm workers either through direct contact with contaminated animal products or though the environment in the form of contaminated manure, wastewater, air, and produce. These findings indicate that a ban on the non-therapeutic and sub-therapeutic antibiotic use could potentially control the rise of antibiotic resistance.

Winning the War Against Pathogenic Bacteria

The threat of antibiotic resistance is now globally recognized. In May 2015, the World Health Assembly adopted a Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance, and in November of the same year the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the first ever World Antibiotics Awareness Week. This has become an annual event since then. The goal of the observance is to raise public awareness and to encourage best practices among healthcare workers, the public, and policy makers. Prior to the adoption of the global action plan, the US, through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention already started implementing a national strategy that takes a four-pronged approach: (1) prevention of infection and the spread of resistance, (2) tracking of infections and collection of samples to monitor resistance patterns, (3) stopping the unnecessary and inappropriate use of antibiotics in humans and animals, and (4) developing new drugs and diagnostic tools.25 These initiatives emphasize the fact that combatting AR requires collaboration among all sectors of society. The public, together with the scientific community, the healthcare industry, the agriculture and food sector, the policy makers, and the pharmaceutical companies, all play a part in the fight against pathogenic bacteria.

Comments: