Background knowledge for teachers

Bilingual vocabulary

The acquisition of the academic language in Spanish is always a vital learning goal embedded in the teaching of the specific content area in our immersion school. For that reason, I would like to start this section by providing a brief bilingual glossary of the most critical terms that students will need to know to express their ideas Spanish during the development of this unit.

In my teaching practice, when I introduce a new topic, and there are new vocabulary words that could be unfamiliar for my students (at least in Spanish), I present the new word, and explain the definition. Often, students use their background knowledge or the relationship between the English word and Spanish cognates to determine the meaning of the new word. As a group, we establish a definition for the word, a proper illustration, or example if necessary, and I create anchor charts that remain in the classroom for students to reference as needed. At the same time, students write the word, the definition, and the example or illustration in their math journals for future references.

|

English Terms |

Spanish Terms |

|

Area |

Area |

|

Square tile |

Baldosa cuadrada |

|

Column |

Columnas |

|

Square |

Cuadrado |

|

Grid |

Cuadriculas |

|

Equation |

Ecuacion |

|

Row |

Filas |

|

Side |

Lados |

|

Lateral |

Lateral |

|

Length |

Longitudes |

|

Array |

Matriz |

|

Model |

Modelo |

|

Graph paper/Grid paper |

Papel cuadriculado |

|

Perimeter |

Perimetro |

|

Additive Property |

Propiedad aditiva |

|

Rectangle |

Rectangulo |

|

Square Units |

Unidades cuadradas |

|

Linear Units |

Unidades lineales |

Important definitions: Area and Perimeter

Even though there are plenty of definitions of Area and Perimeter available, I include the definitions here to maintain the organization and sequence of this unit.

The area of a two-dimensional figure is defined as the amount of space inside the boundaries of the figure. It is a physical quantity that indicates the number of square units occupied by the two-dimensional object.

The area of a two-dimensional surface is measured by finding the total number of same-size units of area required to cover the shape without gaps or overlaps. When that shape is a rectangle with whole-number side lengths, it is easy to partition the rectangle into squares with equal area.

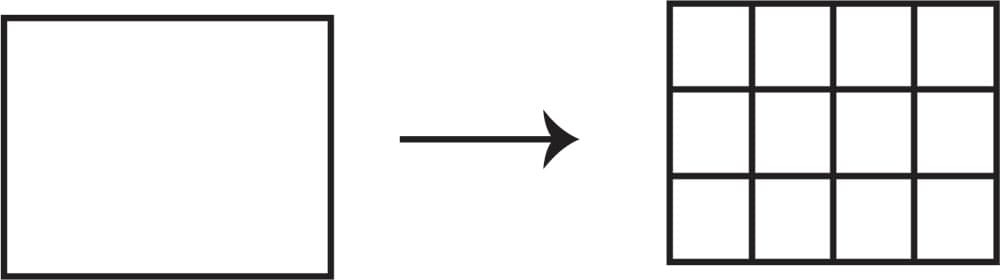

Figure #1: In the example shown, the area of the square is 12 square units because 12 unit squares are needed to cover the surface enclosed by the square.

The perimeter is defined as a measure of the length of the border that surrounds a closed geometric figure. The term ‘perimeter’ derivates from the Greek words, ‘Peri’ and ‘meter’ which mean ‘around’ and ‘measure.’ In geometry, it refers to the continuous line forming the path outside the two-dimensional shape.

As mentioned earlier, the primary purpose of this unit is the implementation of activities for students to understand the differences between area and perimeter. As a result, teachers need to keep in mind the fundamental differences between area and perimeter as listed below.

Area refers to the measurement of the surface of the object while perimeter refers to the outline that surrounds a closed figure. The area represents the space occupied by the object, while, perimeter represents the boundary of the shape.

The measurement of the area represents two dimensions and is expressed in square units such as square kilometers, square feet, or square inches. The perimeter of a shape represents one dimension and is measured in linear units such as kilometers, inches, or feet.10

The sequence of Eureka Math curriculum from multiplication to Area. Where is the confusion?

Hong and Runnalls in 2019 analyzed three different series of Common Core-aligned textbooks and found those popular textbooks present conceptual limitations when introducing the concepts of area and perimeter in elementary grades, and not enough opportunities for students to explore those concepts. Although textbooks are just one component of the instructional process, many school districts require a specific curriculum for instruction. As a result, teachers need to comprehend the limitations in the curriculum to fill in the gaps by implementing tasks that promote reasoning and conceptual understanding. The authors suggest the modification of existing textbooks/workbooks tasks as a way of addressing this need. By modifying tasks, teachers can work within the boundaries of curricular materials while still providing opportunities for students to develop conceptual understanding.11

As Eureka Math is the “district adopted curriculum” for Mathematics, my instruction will follow the sequence and scope suggested in Eureka, but I will modify the way I deliver the content by adding new knowledge and strategies to address students’ misconceptions about the difference between area and perimeter. I will incorporate this unit at the beginning of module 4 (Multiplication and Area).

In 3rd grade, students start the year by learning multiplication facts and the properties of multiplication (Eureka, modules 1 and 3). Then, they transition from making equal groups (equal amount of objects in each group) to rectangular arrays, and finally to area models. Module 2 is about the measurement of time, weight, and capacity, and students get exposed to the metric and customary systems of measurement.

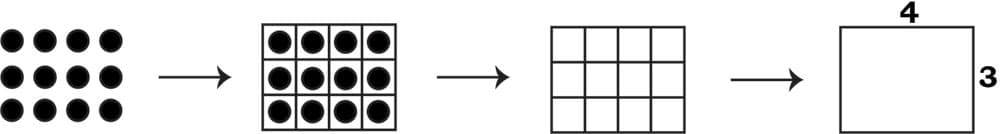

Figure #2. This sequence shows the progression from a rectangular array to area model in 3rd grade.

Equal groups of items, and later a grid representing those items in rows and columns are introduced in modules 1 and 3 to explain multiplication and its properties. In module 4, as the concept of area is presented, items inside the grids are taken away, and students will count the individual squares to determine the area of the rectangle. By the end of the module, the grid system is eliminated, and students will determine the area of the rectangle by multiplying the sides.

Modules 1 and 3 in Eureka Math are designed to set the foundations for the understanding of rectangular arrays to prepare students for area in Module 4. In modules 1 and three students transition from grouping items and adding the groups (repeated addition) they used in 2nd grade to organizing the items in rows and columns or arrays. In those two modules, they also learn the commutative property of multiplication by manipulating the arrays. For example, the array of the example in figure #2 can be presented as three rows of 4 items each for a total of 12 items, or as four rows of 3 items each with the same total.

In module 4 of Eureka, the concept of area is introduced, but the discussion is restricted to rectangular figures, and students start utilizing the grids without items inside. Although the grid with the items inside and the empty grid are both pictorial representations, the blank grid surely requires a more abstract understanding. In general, students don’t face any significant difficulty to count squares and determine that the total of squares equals the area or surface inside the rectangle once the concept of area is defined. The misunderstanding occurs more often when we eliminate the grid and students need to find the area of rectangular figures given the units of one or two side lengths as in the last rectangle in figure #2. At that point in the module, students are expected to be able to make a connection between counting squares and multiplying sides to determine area, as well as with the multiplication arrays they already learned, and to be able to distinguish the concept of perimeter (superficially covered in the module) using the same side lengths they use to calculate area.

In addition to all the above, as module 4 continues, students have to compose or decompose combined rectangles to determine the total area to conclude that area is an additive property. Although Eureka Math includes workbooks for students with an extensive amount of practice problems, the majority of the problems are not designed for students to be able to understand the differences between area and perimeter, or linear and square units, as the focus is more about the repetition and practice of the same skill. I think there is a need for students to be exposed to problems that provide more opportunities for them to explore area and perimeter in the same problem to reason about the differences between the two concepts. To me, that should happen before students are asked to find the area of rectangles or combined rectangles without a grid. Not because rectangles are challenging, they are straightforward, but precisely because of the progression of the content, the way it is presented in the curriculum creates confusion and misunderstandings.

Outhred and Mitchelmore in 2000 published research consisting of observing and analyzing 150 students from grades 1 to 4 while they solved array-based tasks to determine the different strategies students applied and the success of those strategies.12 Their rationale for this research was the consideration that students’ misunderstandings and poor performance when solving area problems are due to the tendency to introduce the area formula too early during elementary school. The authors consider that when students memorize formulas without the understanding of the concepts, they have difficulties generalizing procedures. They noticed that although students were able to calculate the area of a rectangle when given both dimensions, they could not transfer that understanding when finding the area of a square when given only the length of one side. The authors also found that students often struggle when transitioning from physically covering a rectangle with unit squares, an action that suggests an additive process, to the use of the rectangle formula, which is multiplicative. Other common misunderstandings include confusing area and perimeter, applying the formula for finding the area of a rectangle to plane figures other than rectangles, and the use of linear instead of square units for area measurements. The research recommends that teachers should allow students enough time to develop an understanding of the concepts of area and perimeter without memorizing the formulas.

I agree that elementary-age students need concrete manipulation to understand mathematical concepts before the introduction of formulas. Children’s success in understanding area and the perimeter is related to the resources they use during problem-solving. They need objects (tiles, bricks, folded or cut paper) they can fit, fold, match and count so that they can work to develop a conceptual understanding of area and perimeter and their differences. These are my working assumptions in creating this unit.

Sensory Paths

The final project students will complete in this unit involves the design of a sensory path because our school PTA approved the funds to build a sensory path for our students at Zarrow.

Sensory paths are “activity or movement paths” that help kids to build neural pathways or connections in the brain that are responsible for the senses. The high-energy nature of the exercises included in the activity sequence of sensory paths, help kids to complete complex, multi-stage tasks.

A typical sensory path consists of a path in which kids need to complete exercises specifically designed to develop motor skills. The activities require kids to hop, step and jump to get the blood pumping, which helps children to sit still and focus for longer periods in the classroom. Sensory paths are a great “brain break” throughout the school day or during indoor recess.13

Usually, those sensory paths are made with stickers that can be stuck to any surface. At the end of this unit, 3rd graders will apply their understandings of area and perimeter to choose one of the school hallways that may be the best option to build our sensory path. To complete this activity, students will need to consider the available area (enclosing rectangle) of the hallways and the arrangements that offer perhaps the largest perimeter for safe indoor exercising.

Comments: