Classroom Activities

The following are suggested activities to help students to better understand the differences between area and perimeter in 3rd grade.

Important considerations:

Before students engage in the activities, it is important to define what a “unit” is. In this case, one square unit will be defined as one square tile with side lengths of 1 inch.

While tiling, the teacher will guide students in the process of using the side length of the tiles around the linear figures to determine the perimeter.

Later, after students master the differences between area and perimeter, it would be a good idea to explore similar activities incorporating different sizes of tiles to compare unit squares made of one in2 and 1 cm.2

Working with units of different sizes will help students to better understand that the size of the unit we use to measure something affects the measurement. In other words, if we measure the same quantity with different units, it will take more of the smaller unit and fewer of the larger unit to express the measurement.

I will introduce the topic by reviewing multiplication arrays and how are they related to the area of rectangular figures. It is important to refer to the previous units (Modules 1 and 3 in Eureka Math) for students to be able to apply their background knowledge to the study of the concepts of area and perimeter.

Activity 1:

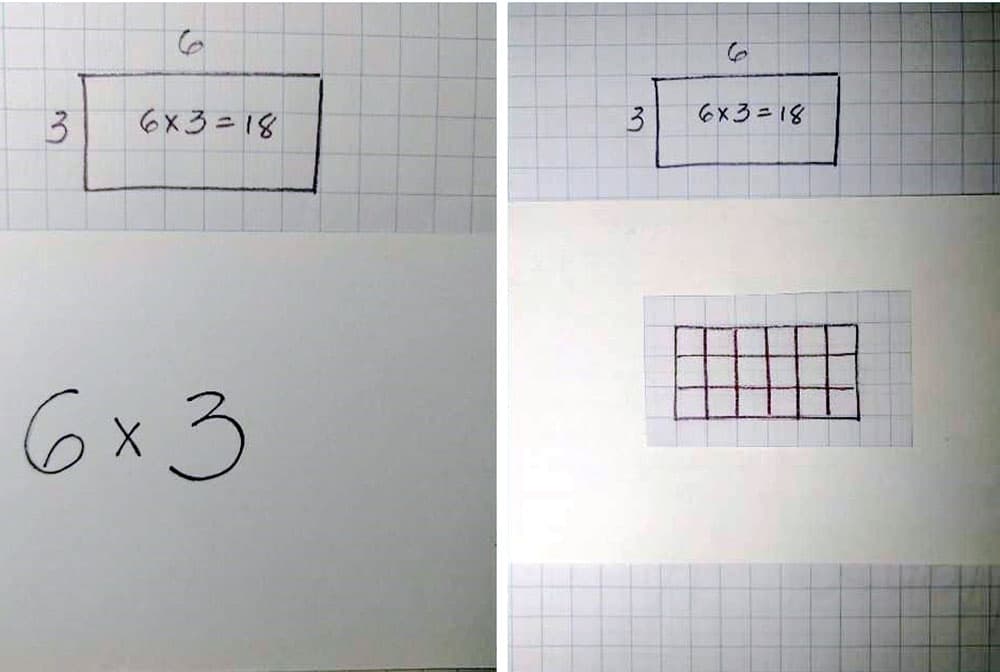

It is a preliminary activity for students to make connections between multiplication arrays and the area of rectangular figures. Students will work in partners for this activity.

Materials:

- Set of cards with rectangular arrays that I will prepare ahead and laminate.

- Pencil or marker

- Grid paper

Directions:

One student will hold a card showing a rectangular array; the other student needs to write the multiplication fact that corresponds to the array shown on the card, draw the rectangle on the graph paper, identify the length of the sides, write the multiplication equation, and the solution of the multiplication inside the rectangle. Each partner with taking turns to continue the game. As the activity progresses, I will question students about the connection between multiplication arrays and a rectangular area.

Variations to this activity may include that one partner shows a card with a multiplication fact, and the other partner draw the rectangular array on grid paper and the solution inside the rectangle. Both partners can continue until they ran out of cards or fill the grid paper with rectangles. To make this activity as dynamic as possible, I will select multiplication facts that generate arrays of reasonable sizes for students to be able to draw them without spending too much time. It is important to keep in mind that the goal of this activity is for students to make a connection between multiplication and area, and not for students to engage in the drawing of large multiplication arrays.

Once all the rectangles are represented, students will determine the perimeter of each rectangle by counting the units around the edges. I will lead a classroom conversation with guiding questions about the relationship between the area and the perimeter of rectangular figures.

During the classroom conversation, I will emphasize the difference between a square and linear units.

Figure #5: Example of activity #1.

Activity 2:

This second activity could be presented as a continuation of the previous activity to emphasize the concepts or as an alternative instead of the first one. If students are in a classroom setting with “Math centers,” they may have the choice of completing one or the other. The goal of the activity is for students to be able to calculate the area and perimeter of rectangular figures.

Materials:

Each pair of students will need the following:

- Blank grid paper. Each square on the grid will represent 1 unit square.

- Two dice

- Markers or color pencils

Directions:

Students will divide the paper in half and decide which half each partner is going to use.

Each partner will toss a die, and whoever gets the highest number will start the game. Both students will use the same sheet of grid paper for their drawings, but each partner will start drawing in opposite corners of the paper.

The first player rolls the dice and will draw a rectangle with side lengths equal to the numbers rolled on the dice. For example, if the numbers were 2 and 4, the student will draw a rectangle measuring two units by four units. Then, the student will write the corresponding multiplication equation and write the value of the area. The second partner will repeat the procedure, creating a rectangle on his or her half of the grid paper.

Partners continue taking turns and creating rectangles. Rectangles must touch one another from any “free” side. The game continues until one partner is unable to draw a rectangle with the remaining space within half of the paper. Each partner each add up the total area of their rectangles. The student with the largest area is the winner.

This activity could be differentiated by providing dice numbered at appropriate levels for each student. At grade level, students may work with standard 1–6 dice. Students ready for a challenge can use polyhedral dice. Students could also calculate the area of the “free space” on each side. In addition to finding the area, which is the main purpose of the activity, students will determine the total perimeter around the compound figures in each side of the paper and will compare their areas and perimeters. As an introduction for the subsequent activity, the whole class will compare their results noticing the cases in which the “side” with the largest area also has the largest perimeter or when, on the contrary, the “side” with the smaller area has the largest perimeter. Those findings will open the discussion about the relationship between area and perimeter. Do rectilinear figures with the same area are expected to have the same perimeter? Does the perimeter increase with the area and vice versa? I will use the results of this activity to guide students in the process of thinking about the possible relationships between area and perimeter. Based on the engagement of the students, I will even suggest they find the perimeter of the individual rectangles in each side of the paper to identify rectangles with the same area that have different perimeters, and rectangles with the same perimeter but different area. This exercise will generate awareness of the differences between area and perimeter and will scaffold the transition to the next activity.

Figure #6: This figure shows an example of the progression of activity 2.

Activity 3:

This activity, although very simple, serves the purpose of illustrating variations of area in rectangles with the same perimeter. It could be added as an alternative for activity 2 or after it to emphasize concept development and the understanding of the differences between area and perimeter.

Materials:

Each pair of students will need the following:

- Blank grid paper. Each square on the grid will represent 1 unit square.

- Pencils or markers

Directions:

Students will work in pairs. Each pair will get assigned a value of perimeter and the task will be to find all possible rectangles with whole-number side lengths for the given perimeter and to find the area of each.

Students will have a discussion of the results to conclude that for a given perimeter, the area is the smallest when the rectangle is long and thin, and largest when the rectangle is as near as

possible to being a square. Long thin rectangles can have less area than nearly square rectangles with the same perimeter.

Figure #7: This figure illustrates an example of activity 3. We can observe that the longest and thinnest rectangle with side lengths 1 by 8 units has the smallest area. On the other hand, the rectangle with side lengths 4 by 5 units, has the largest area in this series of rectangles with the same perimeter.

Activity 4:

In this activity, students will consolidate their understanding of the differences between area and perimeter. The exploratory nature of the activity allows students to deal with both concepts at the same time rather than separately. In my opinion, students should be allowed to compare area and perimeter “side by side” to gain better conceptual understanding. In general, the curricular material available in 3rd-grade mathematics is extensive in the number of exercises presented for students to solve problems about area or perimeter separately, but they offer a very limited amount of examples for students to compare both concepts at the same time, and those examples are often limited to rectangles. In this activity, we will move away from just rectangles, and students will explore what happens when they remove unit squares one at the time. What are the possible arrangements, as well as what happens to the area and perimeter.

To complete this activity, students will work in groups of three.

Materials:

- One sheet of laminated grid paper (1 unit square = 1 in2)

- Foam or plastic tiles (1 in2). Tiles should be the same size as the unit square on the laminated grid paper

- Grid paper to draw on (½ or ¼ in2)

- Pencil and eraser

- Set of recording charts similar to figure #4

- Document camera

- Smartboard

This activity could go in different directions, I may assign the same initial rectangle to the whole class, I could assign different rectangles to different groups, or I may let students choose their initial rectangles keeping in mind that the size will be limited by the size of the laminated grid paper and the number of available tiles. Although the grid paper for classroom use comes in sizes of 11 by 9 inches with a “usable” area of 10 by 7 inches approximately, I will propose that students explore rectangles with smaller dimensions such as 3 by 4, 4 by 5, 6 by 4, etc. to keep the activity manageable during a single classroom period.

Directions:

Students will select “jobs” within their groups. One person will oversee placing the tiles on the laminated grid and removing them (one at the time) to create different arrangements. Another student will replicate (draw) each arrangement on the other sheet of grid paper to keep track of all possible arrangements as they remove the tiles one at the time. The third student will be in charge of recording the possible arrangements in the charts to facilitate further classroom discussion and conclusions.

I will ask my students to observe some conditions when they are removing squares. The main one is, that the squares that are left at any time are connected with each other in the sense that you can move from any square to any other square by passing through the middles of the sides (and not through corners). Also, the enclosing rectangle should stay the same and not get smaller. Together, these conditions guarantee that there is always one square in any row, and one in any column. In other words, they cannot remove any whole row or any whole column. Figure #3 presented earlier shows an example of this activity of a rectangle of 3 by 4.

To make this activity as time-efficient as possible, I will assign the same enclosing rectangle to the whole class. After each group finishes their exploration, they will share all the possible arrangements they found for each unit subtraction (-1 unit, -2 units, -3 units, etc.) with the rest of the class to make sure they have all the possible combinations. Another alternative is assigning a different unit subtraction to each small group of students. As a result, each small group will be responsible for finding all the possible combinations for one type of unit subtraction only. For example, group 1 will work eliminating one unit, group 2, two units, and so on. Once that step is completed, students will make sure there are no missing arrangements for any possible elimination and will determine area and perimeter for each resulting arrangement.

To do this step efficiently, I suggest using grid paper, the document camera, and the smartboard. Students will remain in their small groups, and take turns to draw one arrangement on the grid paper under the document camera for everybody to see the drawing on the smartboard. As the whole group will be following along, the rest of the students will be keeping track of the remaining possible arrangements. Each student that goes to the document camera will draw a new one to avoid repetitions. They will sequentially draw a picture for each possible unit elimination.

Then, students will engage in small group conversations to discuss their findings and establish as many generalizations as possible about the relationships between area and perimeter for their particular examples. I will guide the classroom discussion with questions to scaffold the process. For example, what happens to the area and perimeter when a 'corner square' is removed? What happens to the area and the perimeter if the removed square is in a different position? What happens as they start removing two or more squares? Is there a pattern?. The purpose of the guiding questions should be to promote the understanding that area and perimeter represent different concepts and types of measurement.

Activity 5:

It is the culminating activity of this unit. I chose it because it represents an application problem related to our school life at Zarrow. As I explained previously, our school PTA will sponsor the creation of a sensory path, and I believe my students will feel motivated to be able to apply their knowledge in a “real life” situation at school. I already spoke with my principal about this activity, and she was very receptive about the students’ participation.

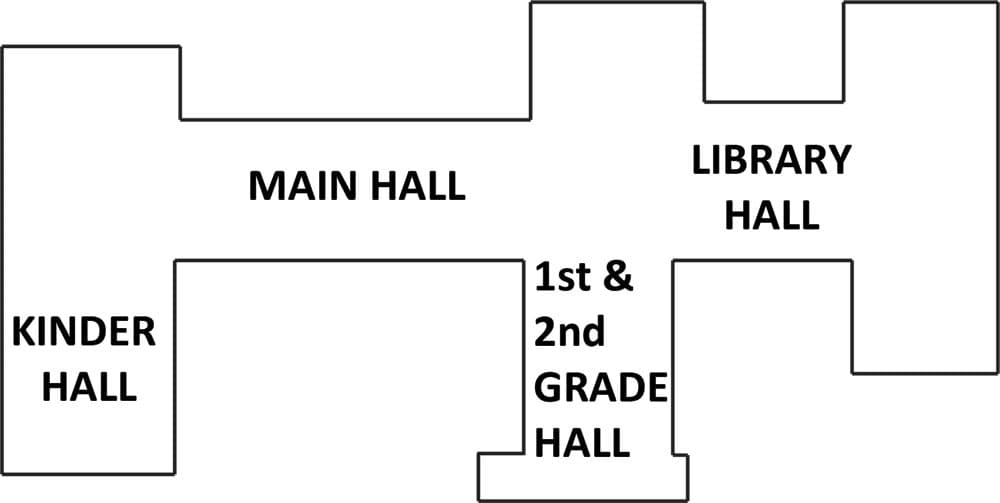

For this activity, students will be organized into four groups. Each group will be responsible for one hall as follows:

Group 1: Kinder hall

Group 2: Main hall

Group 3: 1st and 2nd grades hall

Group 4: Library hall

I have included a diagram of the layout of the school to show the location of the halls that have been considered for the sensory path.

To introduce the activity, I will review the previous learning with the whole class to make students understand that what we are about to do is like the previous activity they completed earlier, but now with an application component.

I will also show a couple of videos (there are plenty online) about different designs of sensory paths in schools, to increase background knowledge and promote idea sharing among the students.

Materials:

- Grid paper to draw on (½ or ¼ in2)

- Pencil and eraser

- Masking tape

Once students get in their groups, and each group has their assigned hall, they will go ahead and measure the side lengths of the halls. The dimensions of the available space will constitute their “enclosing rectangles.” As a result, their designs need to fit within the area of the initial rectangle for each hall. Students will place masking tape to make those limits. Our school is all tiled in the common areas. So, the halls are tiled, and the dimensions of the tiles are 1ft. by1ft. For this activity, 1-unit square equals to 1 ft2 or 1 tile.

When the teams determine the area that they have available, they will go back to the classroom to start working on their design. As a whole class, we will discuss what constraints students have to consider for this project. For example, people will be walking on those tiles, so the designs should allow movement from one side of the hall to the other side. As in the previous activities, the tiles on the design need to connect by their sides, not by the corners, and full rows or columns cannot be removed.

Now, students are ready to outline the rectangle on grid paper, and then, they will start working on the possible arrangements or designs. They will proceed similarly to activity #3, by “removing” tiles from the original rectangle until they determine what arrangement offers the best layout for walking and movement. Students need to draw their options on grid paper like the example in figure #3.

Based on the number of students I usually have per class; each group will have about six students. It allows each student to work with one type of elimination only. For example, one student will try all the possible options of eliminating 1-unit square; another will work eliminating 2, and so on. However, I will not impose that restriction because some teams may decide they want to skip 1 or even 2-unit square elimination and start by eliminating three tiles right away.

Although it will be interesting to see how far students can persist in the unit square elimination process, the main purpose of this activity is not to find all the possible combinations, which would be huge because the halls are large. The main goal of the activity is for students to explore as many options as possible for each hall to finally determine what combination of area, perimeter and design provides the “best” option for a walking path that will be potentially used to design the sensory path.

Once each team is satisfied with their choice, students will outline the design on the hallway floor with masking tape. Each team will have the opportunity to explain their design and the rationale behind their choices.

Figure #8: Diagram representing Zarrow International Elementary School and the four areas that can potentially be used to build our sensory path.

Comments: