Content

What is a Banana?

A banana plant, often called a “tree” is the world’s largest herb, and its fruit is a giant berry.1 This edible, elongated, and curved fruit has a soft pulpy flesh enclosed in a soft yellow rind.2 A single banana is called a “finger”, but a group of bananas is called a “hand.” In some countries, cooking bananas are called “plantains” — they are starchy and thick-skinned — and distinguished from “dessert bananas,” which are usually eaten raw.3 There are more than a thousand types of bananas worldwide. Because plantains have not been marketed in similar fashion to the dessert banana and, up until recently, not found in grocery stores in many parts of the United States, for the purposes of this project, when referring to bananas, I will be focusing on the iconic banana that most of us eat: the Cavendish.4

The History of Bananas

Following the Civil War, bananas became available in the United States. While the Cavendish is the most popular type of banana, it was not the original banana that arrived at American tables. That banana, the one first showcased in the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876, was the Gros Michel. At the time, the closest place where bananas could be grown was Jamaica, and it was Lorenzo Dow Baker who would happen upon the chance of profiting from this fruit as he spotted bananas when he stopped in Jamaica on his way back from Venezuela.5 He decided to load the cargo and sold the bananas for $2 a bunch. Baker was so successful that in 1885 he partnered up with Andrew Preston and founded Boston Fruit — the first commercial banana company — which would eventually become United Fruit Company and is now known as Chiquita Banana.6

Competition soon arrived. In 1900, the Vaccaro family, who were based out of New Orleans and imported bananas from Honduras, established Standard Fruit. It would one day become Dole, as well as United Fruit’s strongest competitor.7 In 1910, Sam Zemurray established Cuyamel Fruit Company, but United Fruit bought out Cuyamel in 1929.8

Amidst the increasing consolidation of the banana industry, the construction of railroads in Central and South America became instrumental to transporting bananas to the United States. In the 1850s, Henry Meiggs, who initially helped develop Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco, fled California amidst allegations of financial improprieties, turning his attention to Latin America. After successfully building early railroads in Chile and Peru, Meiggs was joined by his nephew Minor Cooper Keith, who completed a railroad in Costa Rica, where he planted bananas along the railroad route to feed his workers. Keith ultimately expanded his interests into an expansive banana trading enterprise, which, by the turn of the twentieth century, he sold to United Fruit Company, where he became vice president.9

Yet, alongside these developments, the Gros Michel proved susceptible to Panama disease, a fungus transmitted through soil and water. As a result, American importers replaced it with the more resilient Cavendish variety.10

When the banana first landed in the United States, it was considered a luxury item as it was expensive and arduous to ship. More specifically, importers had to ensure bananas were unspoiled by the time they arrived and sold for a profit at northeast ports in the U.S. In fact, in 1876 a banana cost ten cents apiece — about two dollars today.11 Yet, as of July 2022, the average cost of bananas is 64 cents per pound.12 It wasn’t until the invention of steamships, the extension of railroads throughout the U.S. and refrigeration that bananas became accessible and eventually known as “the poor man’s fruit.”13 And now, bananas, despite being transported from distances farther than other fruits, such as apples, cost far less and are some of the most affordable fruits on the market.14

Figure 1. This graph shows U.S. retail prices of bananas from 1995-2021. Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics. "Retail price of bananas in the United States from 1995 to 2021 (in U.S. dollars per pound)." Chart. February 9, 2022. Statista.

Figure 2. This graph shows the countries that were leading producers of bananas in 2020. Source: FAO. "Leading producers of bananas worldwide in 2020, by country (in thousand metric tons)*." Chart. January 24, 2022. Statista.

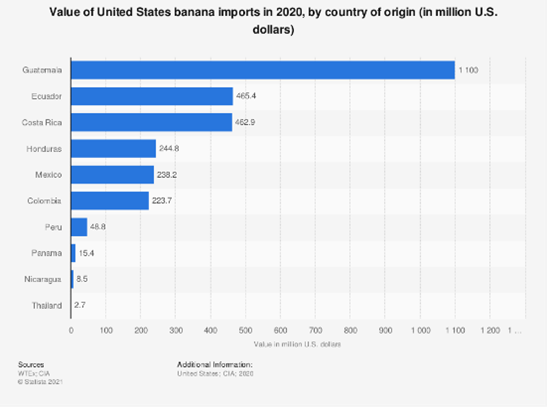

Figure 3. This graph from shows the value of banana imports to the U.S. in 2020 by country of origin. Source: WTEx. "Value of United States banana imports in 2020, by country of origin (in million U.S. dollars)." Chart. July 22, 2021. Statista.

From Where do Bananas Originate?

Banana production is restricted to the tropics as most banana varieties thrive in humid tropic areas where temperatures range between 55° and 105° F. Bananas also require alluvial, well-drained soils.15 The top ten banana producing countries are India, mainland China, Indonesia, Brazil, Ecuador, Philippines, Guatemala, Angola, the United Republic of Tanzania and Costa Rica. However, the top ten suppliers of bananas to America are Guatemala, Ecuador, Costa Rica, Honduras, Mexico, Colombia, Peru, Panama, Nicaragua and Thailand. 16 17 Notably, Guatemala exports almost all its bananas to the United States.18

What is International Trade?

Reem Heakal, a writer and contributor to Investopedia, who covers large-scale economic and financial topics, defines international trade as “the exchange of goods and services between countries,” and goes on to explain: “If you can walk into a supermarket and find Costa Rican bananas, Brazilian coffee, and a bottle of South African wine, you're experiencing the impacts of international trade.”19 With the latter in mind, every time we see or buy a banana at the local grocery store — whether they come from Guatemala, Ecuador, Costa Rica, or Colombia — we are not only experiencing international trade, but we are also participating in international trade. But how exactly have we gotten to the point of being able to directly purchase a banana from the corner store instead of having to fly thousands of miles to be able to purchase or consume one? What are some of the tradeoffs?

For starters, the United States and U.S. multinational companies have played a major role in developing this industry. In the mid-twentieth century, most of the bananas grown in the tropics around the globe were locally consumed, but Latin America had a different story. There, banana production was almost entirely destined for export.20 Two powerful corporations, United Fruit Company and Standard Fruit Company, each exploited the region and penetrated the rainforest as “governments gave […] carte blanche to clear forests for massive banana plantations.”21 And, when mistreated workers in Central America started fighting for better working conditions and pay, U.S. companies reached out to the U.S. Government. As the U.S. Army marched in to crack down on those who challenged business interests, these companies were able to quell rebellion and keep the plantation system stable.22 In its most extreme form, in 1954 United Fruit Company and the U.S. Government orchestrated a Guatemalan coup d'état, protecting their interests in the international banana trade.23 It is in this context that writer O. Henry created the term “banana republic” to describe Latin American countries exploited by U.S. economic interests for their resources.24 25

What is the Banana Supply Chain?

To see this graphically, click here: https://www.nipponexpress.com/press/report/06-Nov-20.html

The journey of a banana from farm to your door is complicated and has multiple moving parts.26 First, bananas grow from a bulb or rhizome.27 After bananas have grown for nine months, farmers on plantations harvest them while they are still green. Then, multinational companies transport the fruit to ports and package them in refrigerated ships.28 Upon reaching their destination ports, bananas are sent to ripening rooms, where ethylene gas is used to speed up the process.29 Bananas are then distributed to local stores and sold. Ultimately, after this long process, U.S. Consumers pay very little, far less than other fruits. Profits remain (to varying degrees over time) for companies along the distribution chain. In fact, when Banana Link, a UK based non-governmental organization (NGO) that works to achieve fair and equitable production and trade in bananas, conducted research (see Figure 4 below) to calculate the distribution of profits along the banana-supply chain of Guatemalan bananas to the U.S., they found that 42.5% goes to retail, 16% goes to transport by truck and ship, 15.5% goes to plantation companies, 12.5% goes to transport and ripening/repackaging, 8% goes to transport warehouses and stores, and only 5.5% goes to plantation and packing house workers.30 This means that workers receive about one cent or less per banana, as bananas currently cost 64 cents a pound and there are about three to four bananas per pound.31 32

Figure 4. The graph above shows the distribution value in the supply chain for Guatemalan bananas into the U.S. Image by author.

What are Guatemala’s Agricultural Minimum Wage & Cost of Living?

As stated above, Guatemala is the number one supplier of bananas to the United States. In fact, in 2020, the U.S. imported $1.1 billion worth of bananas from Guatemala.33 Therefore, this unit uses data from Guatemala as a sample size to gauge a general understanding of the costs of bananas and asks students to think about the agricultural minimum wage and the cost of living in Guatemala to determine how much they think banana workers should be compensated for their labor. This begs the question: How much do agricultural workers in Guatemala earn?

As of January 1, 2022, the Guatemalan agricultural minimum wage was GTQ3,122.55, or about $416, per month.34 But is the agricultural minimum wage enough for workers to meet their basic needs? Based on data from The Global Living Wage Coalition, which estimated that, for 2022, the living wage in rural Guatemala was GTQ3,374 or $440 per month, it is not.35 Because the Guatemalan agricultural minimum wage is lower than the Guatemalan living wage, it is no surprise when the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations states that, “A vast share of Guatemala’s small family farms are unable to maintain their livelihood based on their own farm production and cannot generate their income solely by self-employment in agriculture.”36 In fact, about 75% of smallholder farmers live below the national poverty line.37 Although the Government of Guatemala has established legal minimum wages for the agricultural sector, according to the United States Department of State, “The minimum wage for agricultural and nonagricultural work and for work in export-sector-regime factories did not meet the minimum food budget for a family of five.”38 And, while the Ministry of Labor has attempted to enforce compliance with minimum wage laws, noncompliance, particularly in the agricultural sector, is rampant.39

Additionally, not only is the minimum wage insufficient to provide an adequate standard of living for Guatemalans in the agricultural sector, the number of hours agricultural workers are working is unsustainable. The legal workweek in Guatemala is 48 hours a week, workers are not to work more than 12 hours a day and are supposed to get paid on a 24-hour rest period. What is more, “Time-and-a-half pay is required for overtime work, and the law prohibits excessive compulsory overtime.”40 That said, many employers in the agricultural sector implement production quotas that workers often fail to meet. As a result, workers work extra hours and bring family members, including children, to help meet those quotas. Not only do workers consistently work beyond the legal maximum allowed hours per day, receiving less than the minimum wage, but they also do not receive the required overtime pay.41

What is Fair Trade vs Fairtrade?

In Fair Bananas! Farmers, Workers, and Consumers Strive to Change an Industry, Henry J. Frundt writes that United States’ consumers are becoming aware of the impact of their food choices on underdeveloped societies and are in the quest for fair trade: “the purchase of sustainably produced goods on terms that ensure an adequate livelihood to producers”42 Frundt credits European nations for establishing an early fair-trade system of tariffs and quotas for bananas and details how — for the past century — unlike the fruit sold in U.S. that “came from corporate-controlled plantations in Latin America, where workers labored long and arduous hours […] for little pay,” bananas sold in European nations such as England, France, Spain, Portugal and Greece, were “grown by peasants in the Caribbean, the Mediterranean, or the Canary islands who also labored strenuously but for somewhat better pay than workers in the Americas.” 43 Furthermore, as U.S. companies delivered bananas at bargain rates, poor working conditions, detrimental environmental practices, and paltry wages — smallholders and workers received as little as less than two percent of the portion of the price they paid in supermarkets — and practices came to light, consumers questioned how much fruit cultivation benefited local producers and began demanding fairer bananas.44 But what exactly are fairer bananas?

Given that there are multiple people and organizations involved in the banana production, and “fairness has different meanings for the various participants involved,” fair trade offers a platform, and opportunity for collaboration, to achieve banana fairness.45 In Green Culture: An a-to-Z Guide, Kevin Wehr defines fair trade as “a social movement and an everyday market-based approach to trade that attempts to address the structural inequalities found in free trade markets,” a “more just approach to international trade.”46 To address issues inherent to free-trade practice, fair-trade principles usually include: fair prices, decent working conditions, direct trade with producers, democratic and transparent organizations, community development, and environmental sustainability.47 Fair Trade focuses on exports from developing countries to the developed world and aims to assist marginalized producers to become economically self-sufficient and stable.48 49 Moreover, Fairtrade is helping banana workers unite to advocate for themselves.50 In fact, Peg Willingham, Executive Director of Fairtrade America, affirmed: “It is our mission to ensure all of our certified banana estates fairly compensate workers and empower them to come together to advocate for their rights.”51 Fairtrade acknowledges that collective bargaining will empower and aid workers improve their pay and working conditions, which, in turn, will improve their livelihoods.

Unions in Guatemala

In a report titled, What Difference Does a Union Make? Banana Plantations in the North and South of Guatemala, Dr. Mark Anner found that “non-unionized workers earn less than half the hourly pay of unionized workers and work 12 hours per week more.”52 Therefore, to receive the benefits of collective bargaining, it behooves Guatemalan banana workers to join a union such as SITRABI, the Izabal Banana Workers’ Union, which is the oldest private sector labor union in Guatemala and represents over 3000 workers at Del Monte Foods and its suppliers.53 Unfortunately, unionized workers in Guatemala are threatened with job loss as the banana industry expands in the southern Pacific coast, a non-unionized exporting area of Guatemala that represents about 85 percent of employment in the sector.54 Without robust unions around the country, companies are free to move their operations to other non-unionize regions and continue to pay workers less than a living wage. In addition, “Guatemala has been described as the most dangerous country in the world for trade unionists by the International Trade Union Confederation.”55 In fact, from 2004-2018, nearly 101 labor unionists leaders were murdered, and several more have been tortured or threatened with death.56 Therefore, in his report, Anner recommends that the Guatemalan government do all it can to stop the killing of trade unionists.57 But is the Guatemalan government the only actor, state or otherwise, responsible for ensuring that banana workers are protected and are able to live adequate lives?

What is “Day-O? (The Banana Boat Song)”

In 1956, Harry Belafonte recorded a version of the Jamaican folk song, “Day-O,” a call-and-response work song, for his album Calypso.58 The song is written from the perspective of, and most likely was spontaneously created by, dockworkers who were loading bananas onto ships overnight.59 By 1890, bananas had become Jamaica’s number one export. In a New Yorker article titled, “Harry Belafonte and the Social Power of Song,” Amanda Petrusich states that the lyrics, “Me wan’ go home” is “perhaps a universal plea for freedom as we’ve got.”60 Whether or not what Petrusich says is the case, at minimum, Day-O gives the listener a glimpse into the working conditions of banana workers. What is more, in an interview with Jazz Beyond Jazz, Belafonte said:

The most important thing to me about ‘The Banana Boat Song,’ is that before America heard it, Americans had no notion of the rich culture of the Caribbean…there were these cultural assumptions then about people from the Caribbean – that they were all rum drinking, sex-crazed and lazy – not that they were tillers of the land, harvesters of bananas for landlords of the plantations. I thought, let me sing about a new definition of these people. Let me sing a classic work song, about a man who works all night for a sum equal to the cost of a dram of beer, a man who works all night because it’s cooler than during the day.61

The interview above provides great background information regarding the meaning of the song Day-O, and it states Belafonte’s intended goal of depicting people from the Caribbean in a positive light. Did the average American know, or care about, where bananas came from or who was picking them when Belafonte first sang this song? By incorporating Day-O in this banana unit and teaching students about both Belafonte and his aspirations, we can give credit to where credit is due.

Who was Harry Belafonte?

Harry Belafonte was born on March 1, 1927, in Harlem, New York. He was an American singer, songwriter, actor, producer, and activist.62 He was known for his Caribbean folk songs, calypsos, and for being involved in the civil rights movement.63 In fact, Belafonte was an advisor and confidant of Martin Luther King Jr, as well as financial patron as he helped fund voter-registration drives, Freedom Rides, and the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.64 In the 1960s, Belafonte became the first African American television producer, and, in 1985, he appeared in the charity song, “We Are the World.”65 Additionally, in 1987, he became a United Nation’s International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) Goodwill Ambassador.66 Belafonte currently serves as an American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) Artist Ambassador for the overincarceration of adolescents, promoting a fairer criminal justice system, and has “spent his life challenging and overturning racial barriers across the globe.”67 Most recently, Belafonte founded the Sankofa Justice and Equity Fund, a non-profit organization for artists to use their talents to address issues that negatively impact marginalized people.68

The Banana Split Debate

There are two towns that claim to be the birthplace of the banana split: Latrobe, Pennsylvania and Wilmington, Ohio.69 In 1904, David Strickler charged ten cents for serving three scoops of ice cream between halves of bananas; he even had boat-shaped dishes for serving the sundae.70 Only three years later, E.R. Hazard, served a version of this dessert at his restaurant in Ohio and called it a “banana split.”71 To date, the debate continues, but the town of Pennsylvania purports to have evidence of an invoice Strickler received for his oval dishes.72

Comments: