Content Objectives

The content of this unit is divided into three major sections: the first provides an overview of climate change, including the greenhouse effect, climate drivers, and the evidence for anthropogenic climate change; the second focuses on the National Climate Assessment (NCA) to survey the impacts of climate change, including an overview of the global impacts and a closer look at those specifically impacting the US and the state of Delaware; and the third focuses on climate mitigation and adaptation strategies, with a specific focus on those relevant to our state.

Climate Change Basics

When teaching students about the basics of climate change, it is helpful to break it down into three distinct and more manageable parts: what is it, why is it happening, and how do we know it is happening?

What is Climate Change?

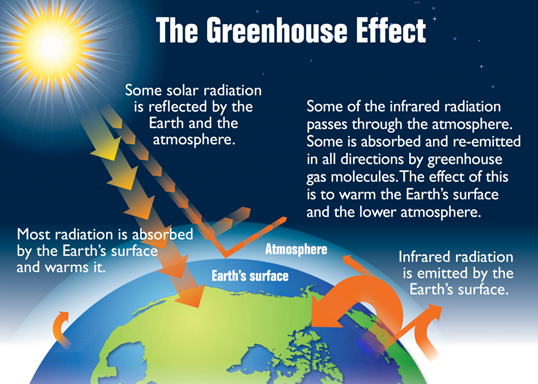

Climate change is the observable long-term change in temperatures and weather patterns; such shifts may be natural (such as through variations in the solar cycle) or human induced.3 Students are also familiar with the term global warming, which is defined as the long-term heating of the earth observed since 1850 due to fossil fuel burning and other human activities.4 In my course, I use the term anthropogenic climate change (ACC) to avoid potential misunderstandings about any geographic differences in temperature changes. Before students can really understand how and why the climate is changing, they need to have a foundational understanding of the greenhouse effect that keeps our planet a hospitable temperature. Figure 1 shows the basics of the greenhouse effect and how global temperatures are impacted by gases in the atmosphere and land cover.

Figure 1: The greenhouse effect. Credit Biology LibreTexts.5

Figure 1 shows how incoming solar radiation (insolation) reacts once it reaches the earth: some of it gets reflected to space by clouds and aerosols in the atmosphere, some of it is reflected by lighter surfaces with high albedo such as ice, and some of it gets absorbed by darker surfaces with low albedo such as vegetation and oceans and then reradiated at longer wavelengths. Gases such as carbon dioxide, water vapor, and methane have chemical properties that trap and reflect the longer wavelength radiation back to the earth, providing a warming effect. Collectively these gases are known as greenhouse gases (GHGs). Without the presence of GHGs in our atmosphere, our planet would be too cold to sustain life, so the greenhouse effect in its natural state is immensely beneficial for life on the planet.6

Why is the Climate Changing?

The natural greenhouse effect has been disturbed by the burning of fossil fuels and other human activities. Since pre-industrial times, humans have added incredible amounts of carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere, raising CO2 concentrations from 260 to 410 parts per million (ppm), and methane concentrations from 1600 to 1900 parts per billion (ppb). The current CO2 concentration is at a level that last occurred some 3 million years ago when temperatures and sea level were both significantly higher than they are today. The dramatic increase in methane is problematic because it is twenty-five times more powerful of a GHG than CO2.7 Human activities have also added significant quantities of other GHGs such as N2O and hydrofluorochlorocarbons (HCFCs), while altering the earth’s surfaces through deforestation and development has dramatically changed albedo.8 These actions have enhanced the greenhouse effect and lead to 1.1 oC of warming since 1901. That number is a global average, and places such as the poles have warmed significantly more over the same time period. Models suggest additional future warming between 0.9 and 3.6 oC depending on different emissions scenarios, with the most plausible scenarios predicting 1.5 to 2.0 oC of additional warming by 2100.9

How Do We Know the Climate is Changing?

Understanding how and why the climate is changing comes from a combination of basic science, historical data and observations, and climate models. Each contributes to the confidence scientists have in stating that the climate is changing and that human activity is the leading cause of that observed change.

The fundamental science of climate change is well understood, as described above. Since GHGs trap and re-emit infrared radiation and warm the atmosphere, increasing the amount of GHGs in the atmosphere enhances that warming effect and temperatures increase. Additionally, changes to the earth’s albedo impact the amount of insolation initially reflected, allowing more energy to be absorbed, re-radiated, and then trapped by GHGs. For example, polar ice and mountain glaciers have high albedos, reflecting a high percentage of insolation. But when that ice melts and leaves pools of water or dry land, the albedo is dramatically reduced and more insolation is absorbed.10

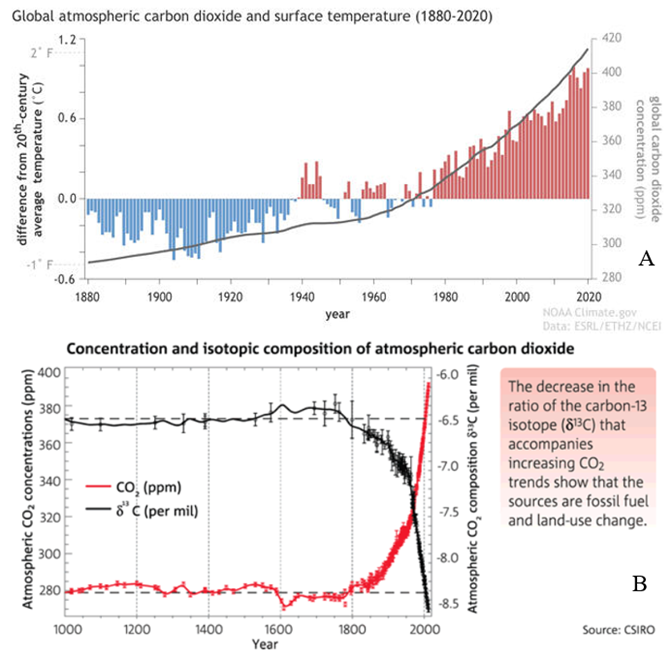

Historical temperature records and atmospheric CO2 concentration data are critical to establishing a clear cause and effect relationship between human activities and climate change. Figure 2A shows temperature anomalies and CO2 concentrations vs time for the past 140 years.

Figure 2: How do we know the climate is changing? A: Global atmospheric CO2 and surface temperature from 1880 – 2020.11 B: Concentration and isotopic composition of atmospheric carbon dioxide.12

The pattern is clear: as CO2 concentrations increase, temperature anomalies from the 20th-century mean increases as well. This increase in CO2 can be traced to human activity by measuring its isotopic composition, as shown in Figure 2B. This specific data shows that the excess CO2 added to the atmosphere by human activities has a distinct isotopic signature consistent with fossil fuels. This occurs because CO2 from fossil fuels is enriched in C-12 and any C-14 in the fossil fuels has had long enough to radioactively decay, such that the CO2 added to the atmosphere is slightly lighter than “modern” atmospheric CO2.13 While there are more historical data to support the fundamental science of ACC (such as paleoclimate reconstructions from ice cores and tree rings), these two sets are sufficient for students to understand the link between human activity and temperature increases.

The final pieces of evidence in linking human activity with observed changes in temperature come from scientific models. These complex mathematical models have been unable to produce the observed warming seen in Figure 2A without the additional CO2 human activity has released into the atmosphere. No other drivers – not solar cycles, changes in volcanic activity, or changes in the earth’s orbit – can account for the observed warming. In addition to helping scientists provide the link between human activity and observed changes, these models are used to predict the impacts of future climate change by incorporating future scenarios for GHG emissions, land use and land cover changes, and complex climate feedback mechanisms.14

Impacts of Climate Change

According to NASA, “the effects of [ACC] are happening now, are irreversible on the timescale of people alive today, and will worsen in the decades to come.”15 This is a stark reality to reconcile with, especially for young people who will bear the burden of this crisis to which they have barely contributed (the same could be said for large portion of the planet’s population). However, I think it is important for students to understand the severity of the looming impacts of ACC to inspire change. One way to do that is to present the impacts on a global scale, a national scale, and finally on a local scale. Each zoom-in increases the relevance to students’ everyday lives. The most obvious and well-known impact of climate change is increasing global temperatures, but a warming planet is only one of many inter-connected responses of the climate system, which include sea level rise, biodiversity and habitat loss, decreases in agricultural production, and intensifying coastal flooding, severe precipitation events, heat waves, forest fires, droughts, hurricanes, and atmospheric rivers. It is these types of impacts and their cause-and-effect relationships that are of specific interest to this unit. It is important to note that the impacts discussed below do not happen in isolation from one another. The key is for students to understand the basics of the impacts but also the connection between a warming climate and the specific process/concept that leads to any one impact. While they read like a list, in reality they exist as parts of an interconnected web, with a warmer climate the primary driver of each impact.

Global Impacts

The primary global impact of ACC is the increase in global average surface temperatures. Data show 1.1 oC of warming already, and models predict an additional 0.9 to 3.6 oC of additional warming by 2100.16 The impacts of even the most conservative warming estimates are significant and troublesome. Broadly speaking, even slightly warmer temperatures will lead to accelerated sea level rise, shrinking glaciers, changing precipitation patterns, lessening snowpacks, a more fragile food supply system, regionally specific adverse health effects, shifting habitable ranges for flora and fauna, ocean acidification, coral bleaching and more.17 These impacts are not uniformly distributed in their nature or their severity. Temperature increases and sea level rise are both prime examples of these regional disparities. Observed and projected temperature increases are worst in the Arctic and less dramatic in other regions.18 Sea level rise will not impact all regions equally: low lying island nations such Kiribati and Palau are and will undoubtedly be more impacted by sea level rise than inland nations like Switzerland or Mongolia. Digging a bit deeper into regionally specific sea level rise reveals that ocean currents and regional geography leave some coastal communities and ecosystems more vulnerable than others. Students should understand that the impacts of climate change, especially on a global scale, are often interconnected in complex feedback loops that can be difficult to tease out and track independent of one another. Doing so often requires a zooming into to smaller national/regional levels and carefully studying specific cause-and-effect relationships.

National and Regional Impacts

Because of the immense size of the United States, the national impacts of ACC are quite like the global impacts in that they are diverse and regionally specific. However, two ACC impacts cut across all regions: changes in seasonal precipitation patterns (Figure 3) and increasing temperatures (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Observed (A) and predicted (B) changes in seasonal precipitation.19

ACC appears to intensify existing precipitation patterns such that wet places are getting wetter and dry places are getting drier. Historical data (Figure 3A) show this happening across the country, with observed changes being seasonal in nature. Projected changes in precipitation (3B) seem to follow that same trend, except in summer where nearly all regions are predicted to experience drier conditions. Observed (4A) and predicted temperature changes (4B) are less regionally biased and seasonal in nature. Except for a few Southeastern states, the entire country has experienced warming over the last century, and all regions are predicted to experience at least 2 oC of additional warming by 2100, with some expected to warm significantly more depending on future GHG emissions.

Figure 4: Observed (A) and predicted (B) changes in temperatures.20

The NCA presents impacts to ten different regions, seven of which are discussed below. Alaska, Hawaii and the Pacific Islands, and the Caribbean are left out partially for brevity’s sake and partially due to their unique environments compared with the contiguous US. Students should note that regional boundaries do not mark hard stops to predicted impacts and that considerable overlap of impacts between regional boundaries is the norm, not the exception.

States in the Northeast, which includes Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Washington, D.C., and West Virginia, are predicted to experience four distinct ACC impacts: 1) less distinct seasonality, 2) changing coastal and ocean habitats, 3) negative outcomes for highly developed and interconnected urban centers, and 4) increased threats to human health.21 Less distinct seasonality with milder winters and earlier spring conditions have already been observed and are predicted to worsen. This will alter the region’s natural ecosystems and environments, negatively impact related tourism, farming, and forestry. Warmer ocean temperatures, sea level rise and associated flooding, and ocean acidification pose significant threats to coastal and ocean ecosystems that support natural environments as well as deeply ingrained commerce, tourism, and recreational traditions. Northeastern states, particularly those located along the Interstate-95 corridor stretching from Washington, D.C. in the south to Boston, MA in the north are characterized by a high degree of urbanization, urban sprawl, and high population densities. These major urban areas in the Northeast are regional and national centers of cultural and economic activity, both of which are under threat from ACC as urban infrastructure, economies, and historical sites suffer from higher temperatures, more extreme precipitation events, and sea level rise. More extreme weather, warmer temperatures, the degradation of air and water quality, and sea level rise all pose significant health risks and are expected to lead more deaths and hospital visits, a lower quality of life, and increasing medical costs.22

The Southeast of the United States, defined as Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas, will experience some of the same issues as the Northeast but is also particularly vulnerable to other ACC impacts. Like in the Northeast, sea level rise will contribute to coastal flooding along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, threatening major urban centers such as Miami, FL and New Orleans, LA, as well as less developed but extremely low-lying rural communities that dot the coast. Intensifying heat waves will make this already warm region of the country even warmer and exacerbate the urban heat island effect across developed portions of the region, such as Charlotte, NC and Atlanta, GA. This region is also home to diverse and unique ecosystems which will be impacted by changing winter temperatures, wildfires, sea level rise, more intense hurricanes, and droughts, all of which have the potential to redistribute species and modify ecosystems. Changing precipitation patterns and more frequent/intense droughts also threaten the agricultural and livestock sectors of the region’s economy.23

The Midwestern states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, and Missouri, are traditionally known as the breadbasket of the United States, leaving their agricultural industries particularly vulnerable to climate change. Changes in humidity and precipitation have already eroded soils, created favorable conditions for new pests and pathogens, and degraded the quality of stored grain. Projected changes in precipitation and extreme temperatures due to ACC threaten to reduce agricultural productivity in the region. Midwestern forests are under threat of invasive species and pests as their ranges expand. The region’s diverse natural ecosystems provide numerous ecosystem services but are threatened by ACC and other human activities, including temperature increases, land-use changes, habitat loss, environmental pollution, excess nutrient loads, and invasive species. This will lead to a loss of biodiversity in the region and less effective ecosystem services. Like in the Northeast and Southeast, ACC poses significant threats to human health due to the increased frequency of extreme high temperature events, poor air quality, extended pollen seasons, and expanded ranges of disease-carrying insects. Similarly, the Midwest’s transportation networks, critical infrastructure, and stormwater management systems are threatened by projected changes to precipitation patterns and flood events.24 Changes in the frequency and intensity of severe convective storms that often produce tornadoes could have a negative impact on the region, but confidence in this connection to ACC is low.25

The Northern Great Plains, which include Nebraska, Wyoming, South Dakota, North Dakota, and Montana, faces significant challenges related to water, agriculture, recreation, and its energy industry as its climate changes. Projected changes in seasonal precipitation patterns, warmer temperatures, and the potential for more extreme rainfall events will exacerbate the region’s existing water management challenges. This threatens the region’s population, agricultural industry, and natural ecosystems. ACC also threatens the region’s booming energy industry infrastructure, which supports individuals, communities, and various integrated economies.26

Most of the Southern Great Plains region faces similar challenges to its northern counterpart. This region includes the states of Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas. However due to some geographic differences across the region the impacts are not as broadly applicable. Most of the region will be impacted by changing precipitation patterns, warmer temperatures, and more extreme rainfall events. The southeastern portion of the region is vulnerable to those issues, but also faces significant sea level rise and threats from more intense hurricanes. Additionally, this densely populated portion of the region is also projected to experience more heat waves, producing similar negative human health impacts as in the Northeast and Southeast regions.27 Like the Midwest, this region is potentially vulnerable to shifting patterns of severe convective storms.28 Both the Northern and Southern Great Plains are home to significant numbers of tribal and indigenous communities, which are particularly vulnerable to water resource limitations, extreme weather events, higher temperatures, and their associated health issues. However, these communities have a unique ecological resilience thanks to their traditional ecological knowledge.29

The impacts of ACC on the Southwest, which includes New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Arizona, Nevada, and California, largely center on water resources. This already arid region has experienced declines in water for both people and nature, and ACC is projected to intensify droughts and change seasonal precipitation patterns that worsen existing conditions. These impacts are made worse by the region’s growing population, which includes some of the fastest growing communities in the country. Wildfires also pose a significant threat to this region. This threat is predicted to increase due in part to ACC, but also due to mismanagement of forest resources for the last century. Increased temperatures and changing precipitation patterns threaten the region’s natural ecosystems that depend on seasonal rainfall and snowmelt. This has the potential to disrupt economically valuable ecosystem services, disrupt natural ecological processes, and reduce agricultural production in the region. The California coast is also vulnerable to sea level rise, and its natural ecosystems are threatened by warming waters, decreased dissolving oxygen, and seasonal ocean acidification events. The indigenous communities of this region are similarly threatened by the increasingly hot and dry climate as those in the Great Plains regions.30

The Northwest, which includes Idaho, Oregon, and Washington, is particularly threatened by ACC because its regional economy is tightly integrated with its natural resources. ACC is already threatening a wide range of the region’s diverse ecosystems, which are tied into tribal and indigenous communities’ cultures and popular outdoor recreation. These threats include changing seasonal precipitation patterns, increased temperatures, wildfires, drought, and warmer and more acidic oceans, which have been described in more detail above.31

Local Impacts to the State of Delaware

ACC’s impacts on Delaware are largely in line with those described for the Northeast. The main areas of concern are sea level rise, changes in precipitation and severe precipitation events, and more frequent and intense heat waves and associated impacts of the urban heat island effect (especially in New Castle County). Each of these specific impacts is discussed in significant detail below. Additional impacts include agricultural losses in the rural sections of the state, negative outcomes for the coastal tourism industry, and various negative health outcomes, but these are beyond the scope of this unit.

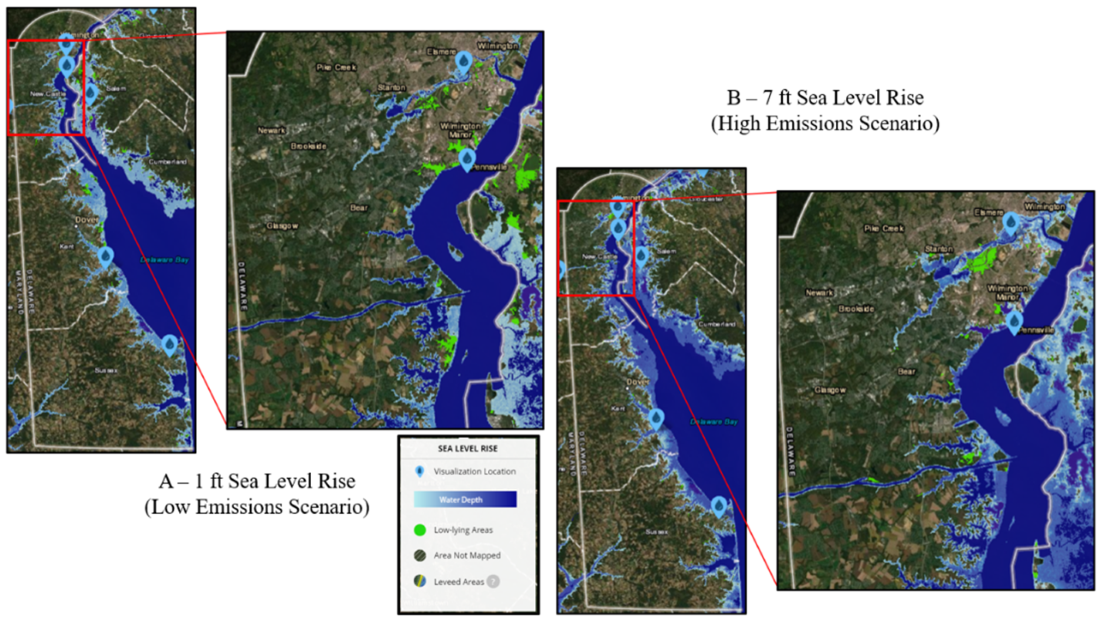

Risings sea levels are the result of two different mechanisms. The first is that melting land ice increases the amount of water in the ocean which raises sea level (although it is important to stress that this applies to land ice only – the melting of icebergs and Arctic sea ice does not contribute to sea level rise). The second is that warmer water expands to occupy more volume, contributing to higher sea levels.32 The combination of these two mechanisms will lead to significant sea level rise across the planet. Delaware is particularly vulnerable to sea level rise because it is the lowest lying state in the country by average elevation.33 Figure 5 shows the potential sea level rise for the one foot (A) and seven feet (B) of sea level rise.

Figure 5: Sea level rise in Delaware and central New Castle County under low (A) and high (B) emissions scenarios.34

Delaware has already experienced more than a foot of sea level over the past century, and rates of sea level rise will increase over the next century. The primary impacts of sea level rise in Delaware are the significant loss of coastal wetlands along the Delaware Bay and damage to coastal infrastructure (including homes, roads, and businesses). Past coastal development (especially in New Castle and Sussex counties) has prevented the natural shifting of existing coastal wetlands, which limits their ability to control erosion rates and sediment flows and buffer against encroaching seas. Other impacts of sea level rise include increased inundation and erosion, increased tidal surges, increased severity of flooding from severe weather events, saltwater contamination of ground and surface water supplies, higher water tables, and loss of critical shoreline habitats and their biodiversity.35

The second major impact the state of Delaware faces due to ACC is changing precipitation patterns as well as the potential for more intense storms. Historical data show that Delaware has already seen roughly five to ten percent more precipitation over the past 100 years (Figure 3A). This observed change in precipitation is seasonal, with the state experiencing slightly drier summers and winters and wetter spring and fall seasons. The most dramatic change is to fall precipitation, which is fifteen percent higher over the past 100 years. The projected changes in seasonal precipitation are less certain, but in general the state is expected to continue to get wetter, with the most significant changes occurring in winter and spring (Figure 3B). In addition to these seasonal changes, the frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation events is projected to increase. Thus, while total summer precipitation may change very little, that precipitation is more likely to fall in bursts associated with intensifying summer storms.36 Something that is important to note is that on a regional basis, it seems that dry regions will get drier and wet regions will get wetter (Figures 3A and 3B). The fundamental link between higher temperatures and increased precipitation is as follows: warmer temperatures lead to higher levels of water vapor in the atmosphere, higher levels of water vapor in the atmosphere and higher humidity levels lead to more frequent precipitation. The connection between ACC and increased storm intensity is less clear but based on similar fundamental scientific principles.37 Increasing precipitation amounts and shifting precipitation patterns will negatively impact the state’s agriculture industry and place stress on the state’s already stressed stormwater management systems (especially in coastal and highly urban areas).

The third major impact facing the state of Delaware is higher temperatures and more frequent and intense heat waves, which have the potential to exacerbate existing negative health and environmental outcomes from the urban heat island effect in the most developed portions of New Castle County. The state of Delaware has already experienced 1.7 oC of warming over the last century and is projected to warm by an additional 1.1 to 1.4 oC by 2039. Perhaps more significantly the minimum (or nighttime) temperature throughout the state is expected to rise by 0.8 to 1.4 oC.38 Rising nighttime temperatures are particularly problematic during heat waves because they limit relief from oppressive temperatures. Heat waves are expected to occur more frequently due to ACC and will degrade air quality, worsen respiratory conditions, and lead to heat-related deaths in vulnerable populations (specifically the elderly, those who work outside, and people without access to cooling). Urban New Castle County can also expect to experience an enhanced urban heat island effect as temperatures increase. The urban heat island is a phenomenon where temperatures in urban and developed areas are warmer than their more rural surroundings because building materials absorb heat during the day and the re-radiate it at night, limiting relief from warm temperatures. This phenomenon is strongly linked to negative health outcomes, including upper respiratory illness, increased incidences of asthma attacks, heat stress, and heat stroke.39 Projections indicate that Delaware will experience its most significant warming in the summer months, with less significant warming in the spring and fall months, and only modest warming in the winter (Figure 3B). Such shifts in seasonality can have negative impacts agricultural production, pest and pathogen control, natural ecosystem function, and ecological resilience.40

Climate Change and People

Most of the above impacts are focused on specific impacts and fail to adequately consider the human aspects of ACC’s impacts. According to the World Health Organization, the impacts of ACC “threaten to undo the past fifty years of progress in development, globally health, and poverty reduction, and to further widen existing health inequalities between and within populations.”41 A warming planet will impact global health by leading to increased death and illness from increasingly frequent extreme weather events, the disruption of food systems, increases in vector- and water-borne diseases, as well as mental illness. ACC has the potential to tear at the seams of social fabrics by reducing overall quality of life, social equality, and access to health care and social support structures. This is especially problematic because these risks are and will be disproportionately felt by the world’s most vulnerable and disadvantaged people, many of whom contributed very little to ACC.42

Student should understand that although significant ecological damage will occur because of ACC, ultimately the planet will survive; at different points in our planet’s geologic history it was a ball of fire, a gigantic ocean with one very hot supercontinent, covered in thick layers of ice, and struck by massive asteroids. Over geologic time, the planet has changed many times and will continue to do so. Whether humans as we know them are part of that continued history remains to be seen.

Potential Solutions to Climate Change

Scientists, engineers, and policy makers have called for iterative and layered solutions ACC, focusing on both mitigation and adaptation strategies. Mitigation involves the use of measures to reduce the amount and rate of future climate change by reducing GHG emissions or increasing their removal from the atmosphere,43 while adaptation strategies are actions taken at various levels to reduce the risks from the already changing climate and to prepare for the impacts of additional changes.44 An effective climate response must involve the integration of these strategies at various scales and must not be limited to physical infrastructure or technological innovations. Instead, it should include significant changes to the socio-cultural structures and behaviors that led to climate change in the first place. What follows is a survey of broad mitigation and adaptation strategies and a discussion of strategies specific to the state of Delaware.

Mitigation

The primary goal of any mitigation strategy should be to reduce or stop the emission of GHGs (especially CO2) since their increase is the primary driver of ACC. This can be done by regulatory policy or technology and associated market forces. In practice this may involve emissions regulations, targeted tax credits, the development of renewable energy (in the electricity production and transportation sectors), and broad economic incentives to reduce GHG intensive resource consumption. A secondary goal of mitigation strategies should be to actively reduce the concentration of GHGs already in our atmosphere, though serious cost and technological burdens underscore the importance of simply slowing and eventually stopping new GHG emissions.45

A major issue in mitigation efforts is that reducing GHG emissions to zero will take time, during which additional warming will occur, potentially enhance greenhouse effect for a long time to come. In addition, the climate feedback system between the concentration of GHGs and temperature is delayed such that emissions today cause warming tomorrow and beyond. The failure to significantly reduce GHG emissions may lead to a tipping point where the systems that control the earth’s temperature spiral out of control in a series of positive feedback loops such that initial warming leads to more warming which leads to even more warming.46 Because of this, effective adaptation measures that prepare for the most immediate and mid-range impacts of climate change are necessary to buy time for mitigation strategies to work over longer time scales, since even if all GHG emissions stopped today, the earth would still warm by at least 1.5 oC by the end of this century.47

Adaptation

Effective adaptation measures are local by nature, yet significant gaps exist in connecting federal and even state policy to local action.48 However, several broad adaptation strategies have been identified as critical to staving off the worst of the impending climate impacts while mitigation strategies attempt to lessen the future impacts. Adaptation strategies include flood control measures such as sea walls and flood gates, enhancing natural water retention services by natural ecosystems, preserving existing and restoring damaged coastal wetlands and mangroves, green infrastructure for dealing with urban stormwater runoff, green architecture aimed at reducing the urban heat island effect, designing more effective water recycling programs and infrastructure, developing drought and heat tolerant crops, and diversifying energy generation to prepare for heat, storm, and demand related outages.49 The implementation of adaptation strategies must carefully consider the costs and benefits of each specific strategy, and their limitations in the face of a still-changing climate must be acknowledged.

The state of Delaware should focus its adaptation efforts on preparing for sea level rise, changing precipitation patterns, and increasing temperatures. Adapting to higher sea levels requires two specific actions: engineering measures to prevent inundation of areas not threatened by the guaranteed one foot of sea level rise and the managed retreat of areas rendered uninhabitable by that amount of sea level rise. Engineering measures include the building of sea walls such as those employed by the Netherlands and in New York to protect their low-lying areas. Strategically placed sea walls can be effective at protecting specific area but are inherently inequitable because the water they displace must go somewhere, leaving those areas to face the consequences. The managed retreat of these areas will likely be necessary. The restoration of impaired coastal wetlands along the Delaware River and Bay in New Castle and Kent counties can help reduce the impact of rising sea levels by reducing erosion and land subsidence and by absorbing excess water. Restoring the barrier islands and coastal wetlands in Sussex County could have a similar effect. Stormwater control systems are also imperative for managing flood waters from both rising seas and increasingly intense precipitation events. Pump systems may also be employed to lower surface water and water table levels to preserve existing infrastructure. Where this is not possible, such infrastructure will have to be moved.

Preparing for changing precipitation patterns and increasing temperatures is especially important for the agricultural industry and urban environments. For those in the agricultural industry, switching to drought and heat tolerant crop varieties (by changing crops entirely or using genetically modified versions of existing crops) is likely necessary. Effective water storage methods are likely necessary to bank water in the fall when precipitation levels are expected to increase, while more efficient irrigation systems are needed to prepare for drier summers. In urban environments, green infrastructure and architecture are necessary to deal with increasingly intense precipitation events, to reduce the impacts of urban stormwater runoff, and limiting the effects of the enhanced urban heat island effect.

Comments: