Unit Content

History of Agriculture in California

Climate change is happening worldwide, and California will be no exception to its impacts. Due to climate change California will experience extreme heat waves, severe wildfires, frequent and intense droughts, inland flooding due to extreme precipitation, and coastal flooding and erosion due to rising sea levels.5 Many of these climate change impacts will increase private, and public costs.6 These impacts will affect humans, animals, the environment, as well as natural resources.7

Learning about the history of California agriculture will give students a perspective of how farming has changed between 1859 and 2007.8 This information is from Olmstead and Rhode, 2017. Between 1890 and 1914, the California farm economy shifted from large-scale animal rearing and grain-growing crops to smaller-scale, intensive crops which include fruits, nuts, vegetables, and cotton.9 By 1910, California emerged as one of the world’s largest producers of grapes, citrus, and various deciduous fruits.10 Table 1 provides key statistics on the transformation of agriculture in California betweenn1859 and 2007.11 Between 1859 and 1929, i.e., in a span of 70 years, the number of farms increased about 700 percent.12 The average size of farms fell from roughly 475 acres in 1869 to about 220 acres in 1929, i.e., about 55 percent smaller farms.13 These changes happened mainly because farmers switched from growing grains to fruit farms. Between 1869 and 1889, the share of California farmland receiving water through artificial means increased from less than 1 percent to 5 percent.14 The switch from seed crops to intensive crops is credited to the development of irrigation methods and practices by California farmers. Irrigation methods included drip irrigation, sprinkler irrigation, flood irrigation, and center pivot irrigation. Growth was relatively slow in the 1890’s, but expansion resumed over the 1900s and 1910s.15 By 1929, irrigated land accounted for nearly 16 percent of the farmland.16 Between 1859 and 1929, the real value of the state’s crop output increased over 25 times.17 Growth was especially fast during the boom of the 1860s and 1870s, mainly because of the expansion of the state’s agricultural land base.18 Successive growth in crop production was mainly due to increasing output per acre and was closely tied to a dramatic shift in the state’s crop mix.19 In terms of the crops produced, and the scale of operations in California agriculture, it was a very different place than it had been 50 years earlier.20

Table 1. California’s Agricultural Development. Reprinted by permission from, “A History of California Agriculture,” Giannini Foundation of Agricultural Economics, University of California, December 2017.

Figure 1 below has information from Olmstead and Rhode, 2017. It shows how cropland harvested was distributed across selected major crops over the 1879-1997 period, and displays the transformation in added detail.21 In 1879, wheat and barley occupied over 75 percent of the state’s cropland whereas the combined total for the intensive crops (fruit, nuts, vegetables, and cotton) was around 5 percent.22 By 1929, the picture had changed dramatically.23 Wheat and barley then accounted for about 26 percent of the cropland harvested and the intensive crop share stood around 35 percent.24 In absolute terms, the acreage in the intensive crops expanded more than 10 times over this half-century while that for wheat and barley fell by more than 33 percent.25

Figure 1. Distribution of California Cropland Harvested, 1879 – 2007. Reprinted by permission from, “A History of California Agriculture,” Giannini Foundation of Agricultural Economics, University of California, December 2017.

Impacts of Lower Annual Rainfall on Agriculture in California

Climate change has changed the amount and timing of snowmelt that feeds our reservoirs. Annual precipitation since the beginning of the last century has increased across most of the northern and eastern United States and decreased across much of the southern and western United States.26 Surface soil moisture over most of the United States is likely to decrease, accompanied by large declines in snowpack in the western United States, and a shift to more winter precipitation falling as rain, rather than snow.27 This will result in a decline of food and fodder in regions experiencing increased frequency, and extended durations of lower rainfall. In California drought has led to fallowing of 540,000 acres of land at a cost of $900 million in gross crop revenue in 2015.28 Food will become more costly. Food production depends on reliable surface and groundwater supplies which decline during periods of droughts. When domestic wells dried out in some rural areas during drought, increased groundwater pumping from deeper wells prevented some agricultural revenue losses. Drought-related agricultural changes have already led to a decline in irrigation in parts of the region.29

Currently, Northern California is experiencing warm and dry weather conditions. It is facing extreme swings between dry and wet conditions. It is facing challenges in managing water for farms, and the environment. 2020 and 2021 were the driest two-year periods on record.30 The drought from 2021 raised farm costs and reduced agricultural revenue. Drought also reduced surface water to farms in 2021 by 5.5 maf (million-acre foot) which is about 41 percent less than normal.31 When farmers have less surface water, they must pump more groundwater which adds to the costs of farming and that impacts the poorer farmers the most.32

History of Increased Temperatures in California

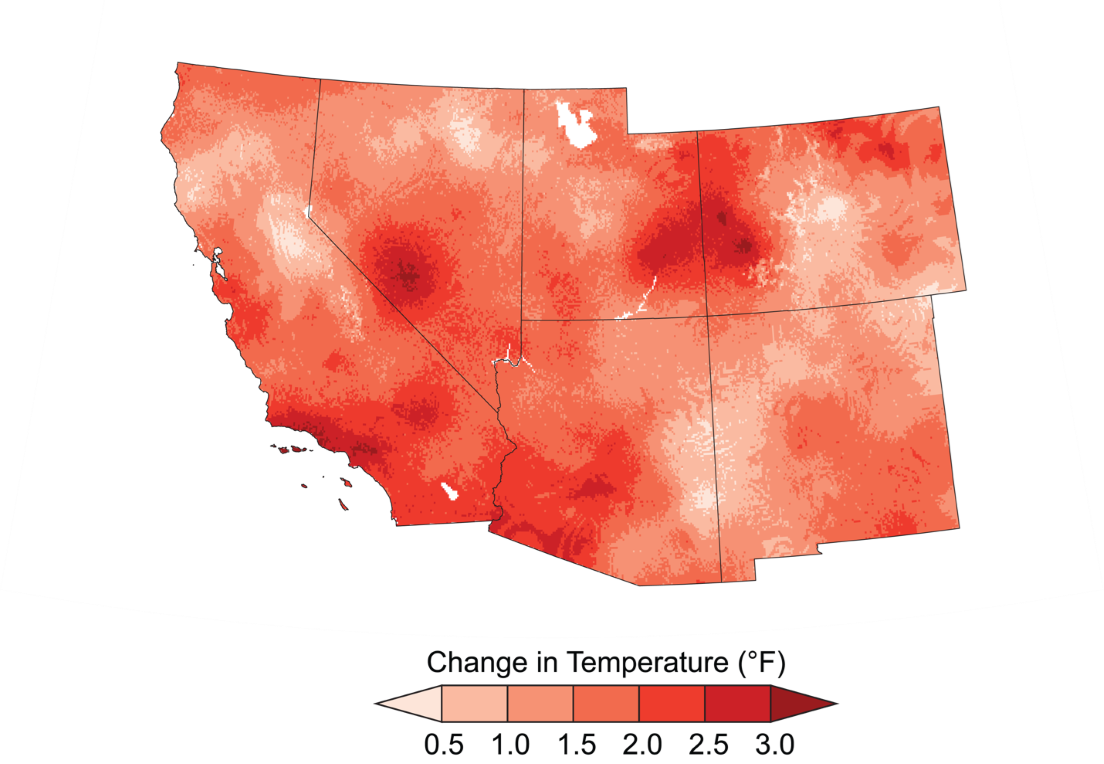

The past 115 years are now the warmest in at least the last 1700 years.33 Global annual averaged surface air temperature has increased by about 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius) since 1901 (Figure 2: Temperature Has Increased Across the Southwest).34 The length of the frost-free season, from the last freeze in spring to the freeze of autumn, has increased for all regions since the early 1900s. The frequency of cold waves has decreased since the early 1900s, and the frequency of heat waves has increased since the mid-1960s.35 Under continued climate change, higher temperatures would shift plant hardiness zones northward and upslope in the United States. Plant hardiness determines if a plant can survive in a certain place and bear fruit. These changes would affect individual crops differently depending on the crop’s temperature threshold. Increasing heat stress during specific phases of the plant cycle can increase crop failures. With elevated temperatures associated with failure of warm-season vegetable crops, it could lead to reduced yields or quality in the crops. While crops grown in some areas might not be viable under hotter conditions, crops such as olives, cotton, kiwi, and oranges may replace them. In parts of California, increasing temperatures would prompt geographic shifts in crop production, potentially displacing existing growers and affecting rural communities. Wine grape quality can be particularly influenced by higher temperatures. Increased levels of ozone and carbon dioxide near the surface, combined with higher temperatures, can decrease food quality and nutritive values of fruit and vegetable crops.36 Because many fruit and nut trees require a certain period of cold temperatures in the winter, decreased winter chill hours under continued climate change will produce fewer buds, smaller fruits, and lower yields, though the vastness may vary considerably.

Figure 2: Temperature Has Increased Across the Southwest. Source: Fourth National Climate Assessment.

Impact of higher temperatures on agriculture in California

For the foreseeable future, with remarkable cuts in emissions, global temperature increase could be limited to 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius) compared to preindustrial temperatures.37 Without significant reductions, annual average global temperatures could increase by 9 degrees Fahrenheit (5 degrees Celsius) or more by the end of this century compared to preindustrial temperatures.38

The number of cool nights has been decreasing since the 1950’s, a pattern that threatens the possibility of growing California’s lucrative wine grapes, fruit and nut tree crops.39 To successfully set fruit, these crops depend on a certain number of “chill hours,” or the number of hours at or below a certain temperature for a particular crop. Because each tree variety has a specific chill hour requirement, farmers select specific varieties of trees to maximize yields in their specific climate zone. Climate scientists predict that in a disastrous scenario, yields of almonds, walnuts, oranges, table grapes, and avocados may decline significantly in the next few decades. Shifting to new varieties with fewer chill hours is often unaffordable, given the typical lifespan of orchards and vineyards which yield crops for a few decades. Much of agricultural production depends on insect pollination. Crop failures and reduced yields can result from increased temperatures that discourage pollinator activity. Not allowing temperature to rise will benefit farmers to continue growing their crops without having to identify alternate crops.

Approaches for addressing water scarcity

Historically, considerable investments were made in water control and supply of water in California.40 The first measure taken by Californians was to drain and protect agricultural land from flooding. To support this, farmers changed their landscape as individual farms leveled the fields and constructed thousands of miles of ditches. In addition, individual farms, and reclamation districts built several thousand miles of major levees to break the state’s inland waterways. Without these investments, much of the Central Valley’s land could not have been planted with intensive crops. The second measure taken was to supply the state’s farms with irrigation water. This accounted for the growth of the state's irrigated acreage between 1890 and 2007 as shown in Table 1.

Constrained water resources and unpredictable precipitation patterns will be among the most challenging effects of climate change for agriculture in California. California is known for its uncertain precipitation patterns. Scientists predict even greater variability in precipitation ahead, and increased intensity and frequency of extreme weather occurrence.41 To address water scarcity, all the available water must be captured during wet years. Groundwater recharge with rainwater during rainy seasons, when possible, will reduce the depletion of this resource. To be able to do so, we need to create the necessary infrastructure to recharge groundwater, have improved storage and reconveyance of water, and build a climate resilient water system. Increasing water recycling and building water catchment systems on farms, will improve self-sufficiency on farms. In addition, farmers can invest in soil preservation to reduce water scarcity. Building soil health by improving the organic matter content improves soil structure and allows

water to better penetrate and be retained for plant access, thereby improving the soils water retention. Organic matter can hold up to 20 times its weight in water. Organic matter also increases fertility and can reduce reliance on chemical inputs and improve plant vigor to better resist pests and diseases.42 Farmers can practice rotational grazing. Rotational grazing is a process in which livestock are moved between fields to help promote pasture regrowth. Good grazing management increases the fields’ water absorption and decreases water runoff, making pastures more drought resistant. Increased soil organic matter and better forage cover are also water-saving benefits of rotational grazing.43 Compost used as fertilizer is known to help the growth of the plant as well as benefit the soil by adding organic matter. Mulch is a material spread on top of the soil to conserve moisture by reducing evaporation. Mulch made from organic materials that are easily available on the farm, such as straw or wood chips will break down into compost, further increasing the soil’s ability to retain water.44

It is important to note that most agricultural groundwater is not priced, while residential water usage is. Agricultural operations pay only for the costs to extract the groundwater, not for the water itself.45 Groundwater also isn’t metered, so it’s unclear how much farms are using, but it’s estimated that groundwater makes up about 40% of farm use in what used to be considered an average year, meaning a year with less intense drought. In a drought year, that farm use share can jump to about 80%.46 Having water used by farmers metered and charged, will allow farmers to know how much water they are using, and the price they need to pay for the water used. This should help bring awareness among farmers about limiting their water usage during droughts. In addition, having allocations and restrictions of groundwater to water decorative grass at businesses and institutions will also help conserve water.

Approaches for irrigating crops during water scarcity

To grow crops during water scarcity, farmers have converted to drip irrigation to improve water-use efficiency. By using a drip irrigation system, water is delivered directly to the roots of a plant, which reduces the evaporation of water that happens in other watering methods. Farmers can also plant cover crops and practice conservation tillage methods like mulch till, and strip till, to improve soil health, so their land can absorb and hold more water and better retain topsoil.47 Additional benefits of cultivating cover crops include reduction of weeds, increase in soil fertility and organic matter, and prevention of erosion and compaction. Doing so, allows water to penetrate the soil and improves its water holding capacity more easily.48

Farmers should be encouraged to use technology to help reduce the use of water. Timers can be used to allow farmers to plan when their crops need to be watered. Farmers can also use a soil moisture sensor to avoid watering crops when the soil has sufficient moisture. Using information from the weather forecast will allow farmers to create an irrigation schedule which they can change according to the weather reports. All the above practices will help farmers conserve water.

Growing less water intensive crops

One of the approaches farmers can take is to switch to crops that require less water. Instead of growing tomatoes and almonds, they can switch to growing garlic and garbanzo beans. When water is short, farmers can fallow annual crops so they can water their almond and pistachio trees, where they have made long-term investments.49 Growing crops that are appropriate to the region’s climate is another way that farmers can grow more crop. Crop species that are native to arid regions are naturally drought tolerant, while other crop varieties may have been selected for their low water needs.50 Olives, Armenian cucumbers, tepary beans, and orach are some of the more drought-tolerant crops. Dry farming is another method of growing crops where farmers depend on soil moisture to produce their crops during the dry season.51 For dry farming special tilling practices and careful attention to microclimate are necessary. Dry farming tends to enhance flavors but produces lower yields than irrigated crops. Wine grapes, olives, potatoes, and apple trees can also be successfully dry farmed in California.52 Organic methods of farming help retain soil moisture while keeping many of the more toxic pesticides out of the waterways. Healthy soil that is rich in organic matter and microbial life serves as a sponge that delivers moisture to plants.53

Comments: