Content Objectives

This 3-4 week curriculum unit will be organized into three sections to scaffold the content and language that students will use in the culminating task. Upon the conclusion of the unit, students will write an argument about the disproportionate impact of flooding on the primarily Black population of Southbridge in Wilmington, Delaware. In the first part of the unit, students will learn key, content-specific vocabulary and build background knowledge about the effects of climate change, both globally, and locally. Students will also begin learning argument structure, and practice the form in writing and discussion activities related to readings and key content. In the second phase of this unit, students will analyze data and gather evidence of environmental injustice in the community of Southbridge. This evidence will prepare students to form and support claims for their culminating task. In the final section of this unit, students will apply what they have learned about argument structure to form an evidence-based argument about the unequal way in which the Southbridge community has been impacted by climate change. Additionally, students will develop a counterclaim with an effective rebuttal. Finally, students will study the advocacy and civic engagement of Southbridge residents that has resulted in a new storm and wastewater system to mitigate flooding in the next few decades. Students will study long-term climate change solutions to increased flooding as they develop the concluding paragraph of their argument, which will offer long-term solutions to flooding in Southbridge.

Climate Change

Climate change is defined by the United Nations as the “long-term shifts in temperature and weather patterns,” primarily caused by human action, such as fossil-fueled transportation, and industrial and agricultural activities.4

Climate change is driven by “the greenhouse effect.” With the help of “greenhouse gasses” like carbon dioxide, earth’s atmosphere traps outgoing infrared radiation and retains heat. As the sun shines on the earth, some of the solar radiation is absorbed by the earth's surface. Some infrared radiation escapes the earth’s atmosphere into space, and some is absorbed by greenhouse gasses like carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide. This natural process is essential to keep the planet warm enough to support human, animal, and plant life. However, since the 1950s, human activities, specifically the burning of fossil fuels, have increased greenhouse gasses in the earth’s atmosphere. As a result, less infrared radiation escapes into space through earth's atmosphere and more is re-emitted to warm the earth’s surface and lower atmosphere, causing the planet to warm.5

Global climate change has caused significant shifts in weather patterns, ecosystems, and oceans. For example, the warming climate is changing ecosystem patterns that affect plants, lifecycles and migration of animals, and growth of crops. Melting glacier ice and thermal expansion in warming oceans are contributing to sea level rise, which in turn has increased coastal inundation. Powerful storms and “extreme weather events”, especially in the eastern United States are growing in frequency, intensity, and duration, posing serious risks to human lives, housing, and health.6

Impacts of Climate Change in Delaware

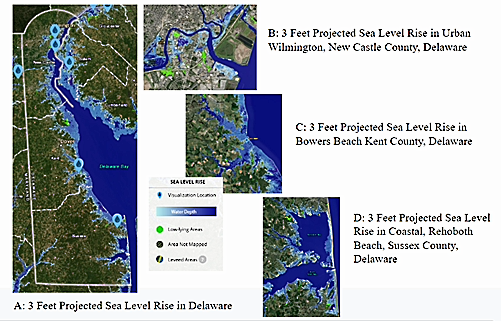

Climate change will have multiple impacts on Delaware with serious implications for infrastructure, agriculture, natural resources, and human health in the state. Delaware is a mid-Atlantic, coastal state that has and will continue to experience increased flooding due to sea level rise caused by melting glaciers, subsidence (or sinking of land), and thermal expansion as ocean water warms.7 Due to the combination of land sinking, sea level rising, and ocean currents unique to the mid-Atlantic region, Delaware and other mid-Atlantic states are experiencing sea level rise that is “faster and higher than elsewhere.”8 The Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC) has projected three potential sea level rise scenarios: low, intermediate, and high (Figure 1). The intermediate sea level rise scenario predicts approximately 3 feet of sea level rise by 2100. The intermediate scenario also predicts the high sea level rise scenario in which the sea level will rise by 3 feet by 2080.9 This projection puts many coastal and urban waterfront communities at risk for partial or total inundation by the end of the century.

Figure 1: 3 Feet Projected Sea Level Rise in Delaware, NOAA Sea Level Rise Viewer10

Precipitation in Delaware is also projected to increase by 10% by 2100. Rising average temperatures will produce more rainfall during winter months than snow. Additionally, the number of very wet days, defined as “2 inches or more of rainfall in 24 hours,” are expected to become more frequent.11 Coupled with sea level rise, heavier and more frequent precipitation will result in more flooding events.12 Moreover, conditions caused by more frequent rainfall puts agricultural crops and livestock at risk, threatens drinking water, sewer, and storm management systems, and poses risks to infrastructure like roads and bridges.13

Impacts of Flooding on Individuals and Communities

A study conducted in 2018 by the University of Maryland’s Center for Disaster Resilience found that urban flooding “is a growing source of significant economic loss, social disruption, and housing inequality.”14 Additional studies have concluded that flooding is the “costliest” of natural hazards when considering the amount of human lives lost or disrupted, as well as total cost of property damage.15

Loss of Property or Property Values

Vulnerable communities characterized by low-income status and higher percentages of people of color “suffer greater property loss in disaster events,” including floods. Many factors contribute to this finding, including a higher likelihood of geographic proximity to “disaster-prone areas” and older, less structurally-resilient residences.16

Costs associated with repairing or preventing flood damage place an added financial burden on residents living in flood-prone communities. Homeowners who seek to flood proof their homes to increase their property values are faced with costs ranging from “tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars.” This added financial burden often prevents many residents from moving away from flood-prone areas, or forces homeowners to sell property at a loss.17

Flood insurance is a measure intended to relieve the financial burden associated with flood damage and repairs. However, purchase of flood insurance is itself a financial burden. According to a 2018 study by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), of households located in Special Flood Hazard Areas, 51% of non-policyholder households are identified as low income.18 This statistic is concerning, considering the fact that many households in proximity to flood-prone areas are low-income. Households that do not have flood insurance due to affordability or lack of access to financial assistance to participate in the national flood insurance program are therefore placed at even greater financial risk.

Both residences and local infrastructure are affected by flooding events. Nearby residences not directly affected by flood damage may still experience effects of flooding by connected infrastructure, like roads. One study found that “a standard 2,400 square foot home with 4% of the nearby roads impacted by tidal flooding experienced a nearly 4,000 dollar loss in property appreciation.” Residences in proximity to a larger percentage of roads impacted by flooding saw even larger decreases in property appreciation.19

A decrease in property value causes a subsequent decrease in tax revenue which affects local services and economic investment in the community.20 Thus, proximity to flood-prone areas can also lead to economic disinvestment in entire communities. Communities characterized by low-income status and exposure to environmental hazards like flooding are made more vulnerable by the increasing frequency of flooding, decreasing property values, lower tax revenues, and flight of economic investment.

Mold Exposure and Respiratory Illnesses

Buildings and residences affected by flooding and water damage are more likely to have mold contamination. One of the most notorious examples of mold contamination after flooding is in the New Orleans area after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. It is estimated that approximately 46% of residences were contaminated with mold after hurricane-related flooding, and 17% of residences showed “heavy mold contamination.”21

Inhaling mold is associated with respiratory infections, especially in immuno-compromised individuals, pregnant women, young children, asthmatics, and the elderly.22 Studies have also linked exposure to mold in water-damaged facilities, like schools, with respiratory symptoms such as wheezing, asthma development or increased severity, and other respiratory illnesses.23

Cleaning a residence to prevent mold contamination after water damage is expensive and time consuming. Recommendations include discarding all items that cannot be washed, as well as removing and disposing of drywall and insulation affected by flooding. Floodwaters in areas with old infrastructure may also contain sewage.24

For communities that experience flooding frequently, the time and expense of clean-up to prevent mold contamination is extensive, and often not feasible. Additionally, chronic flooding leads to chronic exposure to mold contamination. This presents an additional environmental health hazard to flood-prone communities.

Stress, Anxiety, and Mental Health Outcomes

Residents of communities that experience flooding also experience higher levels of stress and anxiety and “in more extreme cases, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder” in the short and long term after a flooding event.25 For instance, Southbridge resident and community activist Marie Reed describes the fear of flooding she has developed since childhood in an interview with Delaware Public Media. Reed notes that when it rains, she doesn’t sleep and she looks out of her window “constantly.”26

Flooding events may negatively affect relationships within families due to financial burdens associated with repairing flood-damaged residences. Residential displacement after a flood event also leads to “poor mental health outcomes,” especially for residents lacking adequate insurance and access to financial assistance.27

Segregation of Urban Communities in Northern Delaware

Wilmington is Delaware’s largest city. Much like cities across the United States, it is broken into racially and socioeconomically segregated communities due to overt discriminatory practices, often supported or wholly endorsed by federal and state government agencies.

In the early 20th century, many Black Americans moved from the rural South to northern American cities, like Wilmington. Black Americans seeking to buy or rent property faced limited housing options, in part due to the discrimination of private property owners who refused to sell to racial and religious minorities, or who added a private covenant to their property deed which prevented the transfer of that property deed to a person of color. As a result, Black Americans, and other people of color, were “confined to discrete residential districts in which the prominent features were substandard housing and overcrowded conditions”28

Additionally, the Federal Housing Administration created and endorsed the policy of “redlining” in the 1930s. Though now illegal after the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, redlining was a government-supported policy in which mortgage lenders in more than 200 cities and towns across the U.S. used color-coded maps to approve or deny homeownership loans. This policy denied federally-insured loans to citizens living in communities deemed less than desirable where housing values were projected to decline. Racially diverse and all-Black communities were frequently identified with the lowest, “D-rating” and were outlined in red, thus systematically barring residents of redlined neighborhoods from obtaining mortgage loans.29

In addition to the devastating socioeconomic, intergenerational effects of redlining, residents of redlined neighborhoods are also disproportionately exposed to environmental hazards. When redlined communities were identified, government and businesses worked together to place polluting industries in these redlined neighborhoods, thereby disproportionately exposing the community to a significant burden of environmental hazards. For instance, to this day, redlined communities suffer from higher levels of air pollutants, regardless of population size or location. A recent study concludes that “pollution levels were higher in 80% in communities” that had been redlined compared to communities identified as more “desirable.”30 As a result of government policies like redlining, the effects of climate change, like flooding, are not shouldered equally. In fact, “people of color are more likely to live in neighborhoods with higher levels of pollution, increased flooding, and power outages caused by heat waves—all directly connected to climate change.”31

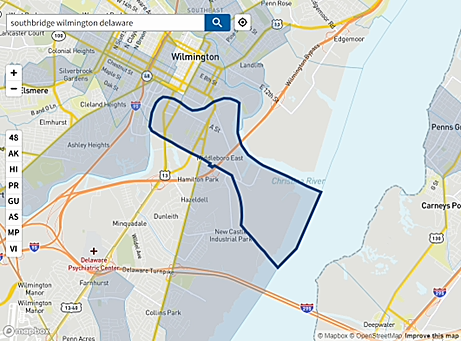

According to a study prepared for the Delaware State Housing Authority in 2003, Wilmington, Delaware is no exception to the national trend of highly segregated cities. The review concluded that residential segregation is not only evident in all three counties of Delaware, but “Wilmington has the highest level [of residential segregation], a condition that has remained virtually unabated over the past 30 years.”32 The community of Southbridge, located on the east side of Wilmington, demonstrates the way in which systemic housing discrimination of the past continues to impact the lives of residents today by exposing them to a disproportionate number of environmental hazards, some of which have been intensified by climate change (Figure 2). Southbridge is an historic, urban community of just over 2,000 residents located on a low-lying floodplain along the Christina River in close proximity to the Port of Wilmington. The community, which has existed for over a century, has seen major shifts in demographic data over time. In the late 1800s, Southbridge was a majority White community, with about 20% of residents identifying as Black. In the early to middle 20th century, a shift in racial demographics resulted in the current majority Black population.33 This demographic shift aligns chronologically with patterns in national and state-level housing discrimination and post-WWII suburbanization trends. The community has also been shaped by a number of industrial, agricultural, and residential uses. Moreover, Southbridge boasts a proud and well-documented history of civic engagement, “religious participation, and Black political leadership.”34

Figure 2: Southbridge, Wilmington, Delaware, Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool35

As of 2023, the community is predominately Black, with 69% of residents identifying as Black, 20% identifying as White, 6% identifying as Asian, and 2% identifying as Latino.36 When narrowed geographically to the core community that excludes the recently developed, more affluent Christina Landing in the same census tract, 83% of the 1,430 residents identify as Black.37 The community is identified as disadvantaged based on the prevalence of burden thresholds and majority low-income household classification. Burden thresholds include a number of factors including, but not limited to, a community’s exposure to climate-related threats, excessive energy costs, health risks, housing conditions, and exposure to legacy pollution. Communities identified as “disadvantaged” are at or above a 90th percentile for one or more burden thresholds, in addition to being at or above the 65th percentile for residents identified as low-income.38

Southbridge is in the 83rd percentile of low-income households across the United States. Southbridge residents are in the 90th percentile of people who have been diagnosed with asthma. Residents are in the 93rd percentile of residents located within five kilometers of hazardous waste facilities, and in the 96th percentile of residents located within five kilometers of one or more superfund sites.39 A superfund site is a tract of land that has been contaminated by hazardous waste that has been improperly or illegally dumped in an area.40 In addition, Southbridge residents are in the 98th percentile of U.S citizens with a projected flood risk to residential properties and businesses.41

This data suggests that the historically unfair housing practices by private and government actors created racially and socioeconomically segregated communities like Southbridge, both directly and indirectly resulting in an unequal share of economic and health burdens, as well as a disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards including both legacy pollution and climate-fueled flooding.

Unequal Impacts of Flooding in Southbridge

Flooding in Southbridge is a case study of the increased frequency of flooding statewide due to the effects of climate change. Though flooding is occurring and of increasing concern in census tracts across the state, the community’s vulnerability contributes to an uneven distribution of health and economic burdens in the wake of flooding events. Additionally, resources to prevent or mitigate the effects of flooding have historically flowed to wealthier communities with more economic resilience.

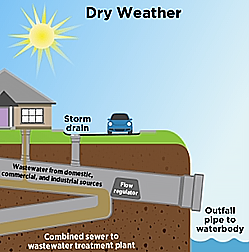

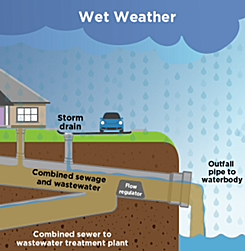

One issue that has contributed to the prevalence of flooding in Southbridge is its aging stormwater infrastructure. Southbridge’s “century-old” storm and waste-water management system has failed with increasing frequency during heavy rains and subsequent high river tides or tidal surges.42 The system is known as a “combined sewer overflow system.”

In this system, both storm and wastewater flow into the same pipes. Under dry conditions, wastewater flows unobstructed to a wastewater treatment facility. However, when the system becomes overburdened during wet conditions, excess water that combines stormwater and untreated wastewater flows into water sources, exposing nearby residents to water pollution including “bacteria, debris, and other hazardous substances.”43

Figure 3a and 3b: Combined Sewer Overflow Basics, Environmental Protection Agency44

This issue is compounded by the periodic opening and closing of old tide gates in the Christina River, which were initially intended to mitigate flooding of surrounding industry, businesses, and residences. However, during a heavy rain in Southbridge, if the combined sewer system overflows during a high tide or tidal surge when the Christina River tide gates are closed, the combined stormwater and wastewater can back up into residents’ homes and streets in the community.45

Until very recently, the issue of aging infrastructure contributing to the flooding in Southbridge had not been addressed by state and city officials. When the nearby Wilmington Riverfront, including the more affluent Christina Landing, began to experience fast-paced redevelopment and economic investment in the early 2000s, Southbridge community activists refused to be excluded from development projects while their community continued to experience decades of chronic flooding.46 Lifelong residents like Marie Reed can recall decades of serious flooding incidents dating back to her childhood in 1947.47

This is a stark contrast to the myriad of federal and state-funded measures taken to address the effects of flooding in some wealthy, and largely White, communities along Delaware’s coastline about an hour and a half south of Wilmington.

For example, in a census tract composed of residences in close proximity to the beach and oceanfront homes stretching from Bethany Beach to Fenwick Island, the 589 residents who live there are in the 98th percentile for risk from climate-change related flooding, like Southbridge residents. However, this community is not identified as disadvantaged because it does not meet the 65th percentile low-income characteristic of a disadvantaged community; in fact, the community is in the 22nd percentile of low-income households. The community is also 98% White.48 Though the community is at a significant risk of flooding due to the effects of climate change, many of these homeowners have much better access to resources to repair damage to their homes, or relocate entirely. Despite this, the state and federal government have historically spent millions of tax dollars to protect this community, and other wealthy coastal communities along Delaware’s coast. Recent expenditures on beach nourishment suggest this spending and investment in protecting these communities will continue into the future, also.

Beach nourishment, or beach replenishment, is the movement of sand to replace sand lost during erosion events caused by sea level rise, storms, ocean currents, and wave action. Without sufficiently wide beaches and dunes, beach communities would experience devastating floods. There are two ways to rebuild beaches and dunes. Sand can be trucked from an inland source onto a beach and spread by earth moving equipment. Alternatively, sand can be dredged from offshore and pumped back onto the beach through pipes; the sand is then shaped by earth moving equipment to rebuild the beach and/or dune.49

According to DNREC, beach nourishment has occurred since the 1950s, but has accelerated since the early 2000s to protect coastal communities.50 In a 2001 study of the cost of maintaining Delaware’s beaches, authors note the economic consequences of beach nourishment on local property owners, Delaware residents, and visitors to Delaware beaches. The study estimates that beach nourishment costs totaled over 18 million dollars from projects in 1989, 1992, 1994, and 1998 alone.51 Moreover, the study described the invested interest of real estate and property owners as beach nourishment raised property values. Of the projected 15 million dollars in benefits resulting from the proposed beach nourishment in 2001, “benefits to residential beachfront property owners totaled $12.7 million.”52

In addition to the millions of dollars spent in beach nourishment since the 1950s, the state recently approved a 50-year project facilitated by the Army Corps of Engineers that will replenish beach and dune areas stretching from Rehoboth Beach to Fenwick Island to mitigate the effects of coastal inundation. The project, started in 2023, is estimated to cost the state and federal government a total of 24 million dollars that “includes initial construction costs, periodic nourishment, major rehabilitation, and project monitoring.”53

The ways in which flood-prone communities in Delaware have historically received or been denied government intervention to protect lives, homes, and businesses vividly demonstrates environmental injustice as it relates to the effects of climate change. In an urban, low-income, and primarily Black community like Southbridge, flooding has caused unsafe housing and economic disinvestment, as well as increased prevalence of health issues for decades. Meanwhile, in higher income, largely White communities on Delaware’s coastline, millions of state and federal tax dollars have been spent and continue to be spent to mitigate flooding; this action has simultaneously increased the value of private and commercial residences while also stimulating development and economic investment that benefits the wealthy local community of beachfront property owners.

Advocacy and Action in Southbridge: Past, Present, and Future

Due to the advocacy of Southbridge residents and efforts made by the Southbridge Civic Association in partnership with the South Wilmington Planning Network and other organizations, a new, 26-million-dollar wetlands park opened in June of 2022 to provide recreational opportunities to local residents and mitigate future flooding. In addition, the project will update and separate the combined sewer and stormwater management system in Southbridge to prevent further contamination of local water sources and mitigate potential flooding of residential basements. The updated sewer and stormwater management system is expected to be completed by the end of 2023.54

This is undeniably a positive outcome for Southbridge residents, and a formal neighborhood action plan highlights the importance of resident leadership and involvement in further development of the area. Most specifically, recommendations include protections for Southbridge residents against the gentrifying effects of new residential and commercial development on the Wilmington Riverfront that is already shifting the community’s racial and income demographics.55

Moreover, sea level rise and legacy pollution continue to pose a risk to the Southbridge community. For example, if sea level rises four feet, about one foot above DNREC’s intermediate projection for the state of Delaware, the new wetlands park will be underwater by 2100. Harmful pollutants from Southbridge’s industrial legacy will also pose risks for residents if sea levels rise and overburden new systems intended to prevent residential exposure to pollutants in the soil.56

Additional solutions to sea level rise exist, and will likely be innovated upon as the effects of climate change become more intense and put more citizens at risk. One such solution to sea level rise is the use of “freeboarding” in new housing development, or adding freeboard to existing homes. A house that is freeboarded is elevated so that the lowest floor of the home is above predicted flood elevations, usually between 1 to 3 feet. Residents who freeboard their homes are at a decreased risk to flood damage and are eligible for a reduced rate of flood insurance.57

The financial responsibility of who should bear the burden of updating homes with freeboard in places like Southbridge is complex. While local government may argue that financial responsibility should be entirely shouldered by residents of Southbridge, others may argue that government practices directly and indirectly segregated the community to a vulnerable floodplain that faced systemic disinvestment as a result. Moreover, millions of federal and state tax dollars have been spent, and continue to be spent, on beach nourishment to protect wealthy, oceanfront communities from the effects of sea level rise.

Comments: