Content

Part 1-The Dominant Narrative

Gold was discovered in California in 1848 almost simultaneous with the cession of the state by Mexico to the USA. A rush “Forty Niners” came to the region in 1849 and brought the Anthropocene to the state in a big way in a few very short years. Industrialism developed in other regions of the US in a steady evolution from water wheels and canals to steam engines and factories. In California the destructive power of industrialism arrived all at once. Mining became an industrial scale enterprise within a few years with all its exploitation of land and labor along the way.

The painting titled “Miners in the Sierras” is among the earliest to depict the California Gold Rush6. It was created in 1850-51 by Charles Christian Nahl and August Wenderoth who as immigrant/refugees from Germany gave up looking for gold and set up a studio in San Francisco. Their purpose of the painting was to show the importance of California to the future of the US. The miners’ red, white, and blue shirts supposedly symbolizing the US flag. The few miners in the painting are laboring alongside a river in a fertile lush mountain scene. There men appear to be working cooperatively and pleasantly. Some elements of interest in this oil painting are the clear blue skies and crystal clean water. The mountainsides are a mixture of bright greens and browns. And there is a neat, well-built house in the center of the middle distance—presumably where the miners go home to at night. Interestingly the house chimney is smoking which implies someone is home at midday—which was unlikely considering white women were rare in California at this time. This painting is portraying a dream-like idealized version of what would become called “Gold Country.” In the Sierra Nevada. This painting was produced in San Francisco in the early years of the Gold Rush, and it celebrates the dreamlike version of the Gold Rush many people still hold in their mind as what this period was “truly” like. This version of the story sticks with us, even though by the mid 1850s mining had already begun to change.

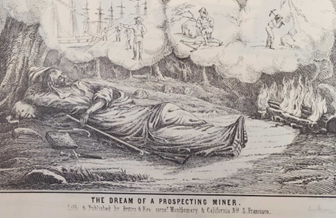

Figure 1: The Dream of a Prospecting Miner, Lithograph ca. 1848-59.

Students will also analyze the lithograph “The Dream of a Prospecting Miner” (fig. 1) which was sold on Letter Paper by Britton & Rey between 1849 and 1859. This was a kind of cheaply produced print which was faster and less labor intensive than earlier forms of printmaking. As such it was a type of image that could be created and sold remarkably quickly in response to customer demand.7 In the picture the miner is literally drawing of future wealth, and in his dreams, he is working alone, and finds his fortune alone. This idea corresponds to ideas of American individualism in the mid 19th century. The idea of the rugged “mountain man” who can blaze a trail through the wilderness in the tradition of Kit Carson, John Freemont, and others. In this case, that individual glory is marketed to US American men of any type. If you can buy a shovel, a gun, and get yourself to the hills of Gold Country, you too can be the hero of your own dreams.

Part two - the Counternarrative of Chinese men and Corporations.

The counter narrative to the imagined lone miner in the wilderness is quite a bit messier, and a lot more crowded. Firstly, the Miners who arrived were not all white US Americans, the first sizable populations of immigrants to arrive were from China and South America, and this unit will focus on the Chinese portion of the non-white, non-English-speaking population. The dream of “Gum San” (金山) or in English, “Gold Mountain” drew Chinese men with the same hopes and dreams that drove all “Forty Niners:” get rich and go home with a small–or large–fortune. And secondly, most miners didn’t work alone in the wilderness. Camps of groups of men grew up as Gold Country got crowded fast, and land claims were side-by-side nearly immediately.8

From the start Chinese immigrants were segregated from English speakers by language, culture, and religion. Chinese immigrants formed mutual support groups in San Francisco based on dialect and shared region of origin almost immediately. Men who were strangers in China entered gold country in groups formed in California.9

Chinese miners who were “ubiquitous” in Gold Country by 1852, found they needed to stick together for safety.10 They were targets of violence, robbery, fraud, and discrimination. This outsider status was reinforced in People v. Hall (1854) Chinese immigrants were categorized with Amerindians and African Americas as persons who were prohibited from testifying in court or voting.11

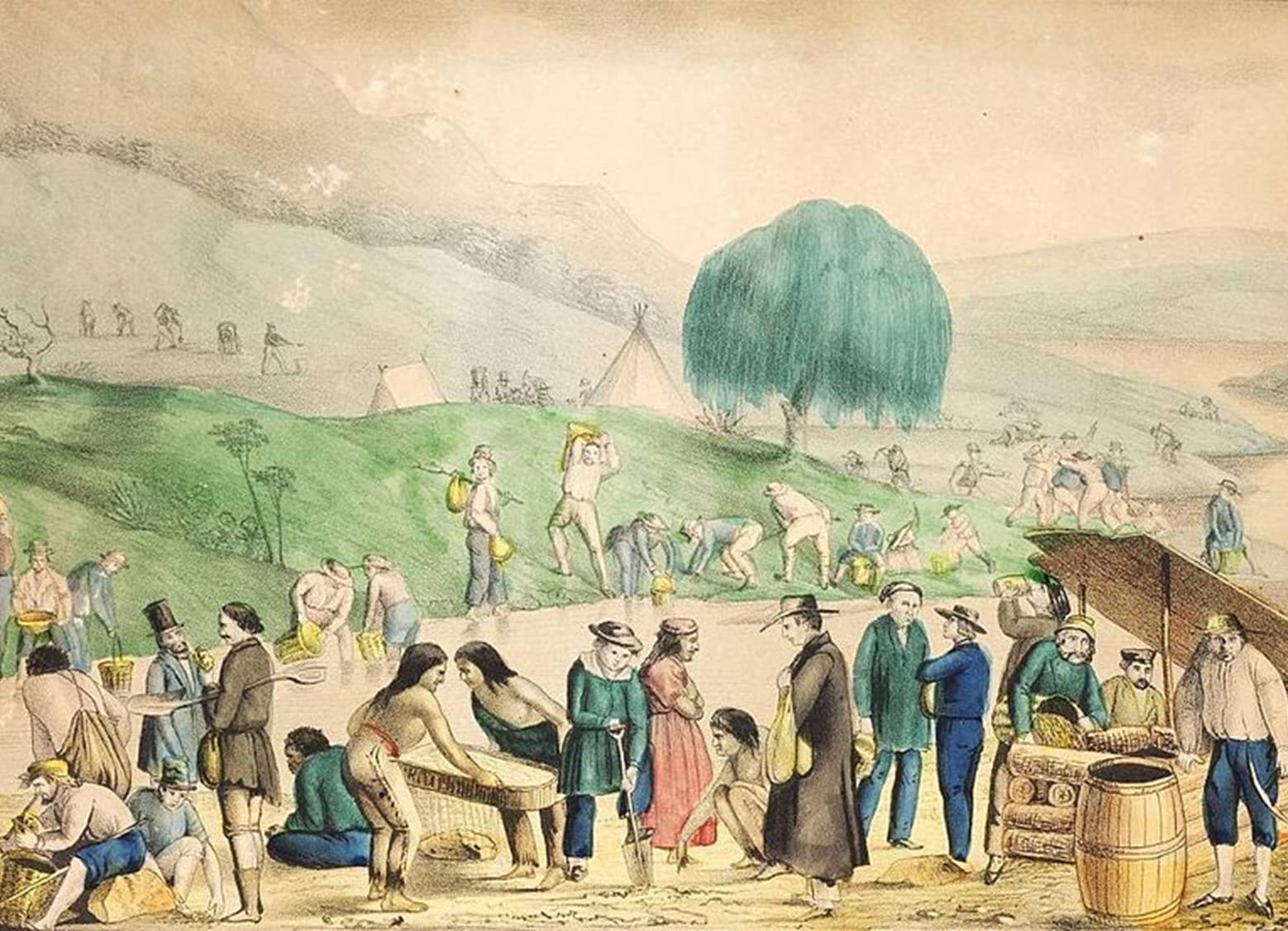

Figure 2: Gold Diggers, Lithograph 1849

In 1849 Kelloggs & Comstock, lithographers in San Francisco produced this print (fig. 2) titled “Gold Diggers”.12 Lithographs like this one were printed in one color (usually grey or sepia) and then patches of color were added by hand, often by women or children working in the printmaker’s studio. This image depicts a far more chaotic mining experience than Nahl and Wenderoth. In many ways it is more accurate, as rivers with rich placer deposits attracted hundreds of claims. Joseph Banks, on the ground in 1850 described how newcomers arrived in “almost one continuous stream of men. Every place is snatched up in a moment. This canyon is claimed to its very head, nearly 20 miles, each man being allowed but 20 feet.”13 The people are gathered around the Sacramento River, and the people in the foreground are doing a variety of mining tasks. The people appear to be of diverse but uncertain origins, the person in black at the center right might be a priest, two African American men appear in the lower left corner, and there appears to be some kind of brawl in the right midground. The image conveys the diverse attitudes, dress, and habits of people who came to search for gold, although it does not appear to have any explicitly Chinese individuals. It is not remote or isolated or as much in the “wilderness” as appears in the first painting.

Mining in California quickly became competitive: areas with rich deposits were crowded. White men kicked Chinese men out of their claims–often violently.14 The Foreign Miners Tax was instituted which was heavily enforced against Chinese Men –because they were the most visibly foreign.15 This taxation created a contradictory set of incentives. Chinese miners were a good source of tax revenue for local jurisdictions--between 10% and 50% of state tax revenues between 1850 and 1870--while adding little demand for any public services.16 On the other hand, Chinese miners were in direct competition with white men for claims to gold.17 In most locations they were marginalized but tolerated.

Figure 3: A Group of white and Chinese miners at a Sluice Box in Auburn Ravine, photo by Joseph Blaney Starkweather 1852.

This photograph (Fig 3) was taken in Auburn Ravine in 1852.18 Many copies of it exist, some of which have been colorized. White miners stand on the left side of a “Long Tom” sluice box. On the right side are four Chinese men identifiable by their shaved forehead hairstyle, and loose-fitting clothing. This image shows the proximity of the land claims which were “worked” by different groups of miners, and the casual nonchalance of mining directly adjacent to people who may not share a language in common.

Students should discuss how they feel about the veracity of a photograph compared to a painting or lithograph. Photos have a power of realism that reaches us in a way that feels more real than a painting or drawing. There are incidental details in the photo which add information that may have been unintended by the photographer. For example, the buildings in the background indicate that this claim site is not amidst wilderness. Some questions to consider are what truths does this photo tell us that Nahl’s painting does not? And what truth is hidden by photos like this one that might be expressed more in a painting?

Students will compare the Auburn Ravine group photo with studio portraits miners paid to have taken. Studio daguerreotypes taken in San Francisco in 1850 show white miners with the tools of their trade. One portrait of special focus is of an unnamed Chinese man taken by Isaac Wallace Baker.19 These portraits, presumably commissioned by the sitters, make us feel the humanity of the individuals who came to find their fortune in California.

Only a few years after the Gold Rush began, mining in California industrialized. The easy method of panning for placer gold in the river was replaced by more efficient mechanical inventions which made it possible to access the veins of gold more directly. Rivers were dammed and diverted to mine the riverbed. This required the skills to build dams and water diversions. Many Chinese men already had the water management skills to build the necessary canals and pumps to move water out of the diggings. But why would Chinese immigrants be better at this than English speakers?

Most early Chinese immigrants to California came from four districts known as Siyi 四邑 (Sze Yup) in the Guangdong 广东 (Kwangtung) province. Most people in this region were poor farmers. A minority of Chinese immigrants came from three districts known as Sanyi 三邑 (Sam Yup) and were more likely to have more education and experience in trade and business. Both groups were familiar (in different ways) with the systems of flooding and draining water for rice farming.20 The skill and knowledge from Chinese rice paddies was easy to transfer to the Sierra Nevada. The pumps most relied on by miners to drain rivers, and the tamped earth canals and flumes to divert water out of its natural course were built largely by Chinese men. So much so that even in places with few Chinese laborers the most common type of pumps were known to everyone as “Chinese pumps.”21

Often people point to the lack of evidence of specifically Chinese mining tools and techniques remaining in the Sierras. This ignores the fact that most productive areas were re-mined during the 1930s depression, and older artifacts would have been moved or destroyed. There is evidence that some of the Chinese immigrants were not just farmers or merchants and had prior experience in placer and lode mining. Chinese mines in Yunnan, Sichuan, Jiangxi, and Hunan were active on and off for thousands of years. David Valentine argues in his article “Chinese Placer Mining in the United States” that if China had mines, it had miners, and if those miners were relatively nomadic within China, they could easily make the choice to leave their homeland amidst the chaos of the Opium Wars (1839-64) and the Taiping Rebellion (1851-64) and head to California. If the largest number of emigrants came from Guangdong 广东 (Kwangtung), it is likely some of them were professional miners. That region had large non-agricultural mountainous areas with deposits of coal, gold, iron, lead, silver, and tin. This means that Chinese immigrants were more likely than the average US American to have the skills and knowledge to do well for themselves in any kind of mining.22

Industrial Mining Corporations Employed a lot of Chinese labor.

Chinese men looked the most foreign and had the largest language barriers to integrating with the other miners. However, employers recognized they were sober, hardworking, and in some ways superior to US American workers23. Many companies hired Chinese men to do specialized work like dig canals and build pumps. Sometimes Chinese men were hired to work in the same jobs as, but segregated from, white men. Chinese immigrants were usually less than a third of the workers, however they were willing to do the work white men refused to do. Just like their work on the railroads, Chinese laborers always received lower pay.

In some places Chinese men were driven out of mining wage work with violence. In a letter from Mariposa in 1856 a miner notes “The rapid increase of this class of people,” by which he means the Chinese, “began to incite alarm in the minds of our working and mining population, in many places they [Chinese immigrants] became a source of great annoyance, which results in many acts of violence towards this unfortunate race.”24 In these cases Chinese men were limited to hand panning the tailings of industrial mines, or hiring themselves out as wage labor in boom towns doing laundry, or cooking. The association of Chinese men with these marginal jobs served to reinforce stereotypes white people already had.

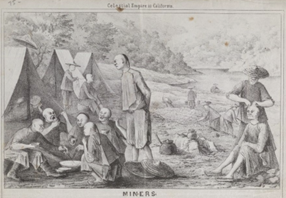

Figure 4: “The Celestial Empire in California” Lithograph ca. 1848-59

Chinese men formed their own communities within or at the edges of white towns. Some of their settlements continued to be temporary in case their residents needed to pick up and leave town at a moment’s notice. In this image (fig. 4) from the Beineke Manuscript Library at Yale University we can see some of the judgmental attitudes of the artist towards Chinese miners.

This image was printed on large sheets the size of modern “letter paper.” The image takes up half of the 11”x 14” page and the rest is left blank for the writing of a letter. Individuals wanting to send a letter home from California could purchase a sheet of Letter Paper with one of several available images at any given time. This image titled “Celestial Empire in California--Miners” was popular enough to make it into a set of souvenir reprints 100 years later.

The unnamed artist of this image gave the Chinese men serious and grumpy expressions. The men are clothed in loose cotton clothes with the queue hairstyle common to Chinese men of this period. Some individuals are eating with chopsticks, one in the right foreground is getting his head shaved, and one in the left midground is having his hair braided. In the background other men are panning for gold. Elements of Chinese culture that seemed exotic and foreign are abundant. The clothes, shoes, hairstyles and “basket hats” are everywhere. The cooking fire has a tea pot in the central place, and the men appear to be eating out of a communal pot while squatting on the ground.

It is important to note the unique clothing and hairstyles of Chinese men made them seem more foreign than other immigrants. Chinese men were judged sometimes to be more feminine than white men because of their long, braided hair, and loose flowing clothing. Many English-speaking immigrants to California would have been educated enough to project Orientalist prejudices common at the time. British, and Australian immigrants may have even had personal experience in Southeast Asia and brought with them ideas of the feminized Asian.25 In the larger cities Chinatowns developed as a safe space for Chinese men to form safe communities. In smaller towns there was still a desire to form a group for safety and comfort. In mining camps, the Chinese camp was its own segregated community.

Part three: California and Global Markets for Cinnabar and Mercury

Gold mining developed in relationship with other industries. The most obvious need was Ironworks to provide the tools for mining. The less obvious need was for quicksilver. Mercury, which most people know from its use in thermometers and other scientific equipment can also be used to absorb gold dust out of sand or sediment. Panning for gold works because gold dust is heavier than sand and sediment, but fine particles are difficult to collect and purify. Mercury is liquid at room temperature and absorbs gold particles into a mixture that can then be heated until the mercury evaporates leaving behind pure gold.

This created demand for the miracle material of mercury. The first mercury mines in Alta California were in the New Almaden hills, at the southern end of South San Francisco Bay.26 The mine complex was started in 1845 with a license from Mexico City. Local demand for mercury increased after gold was discovered. In the 1870s the New Almaden Mines opened and both mine complexes produced enough mercury to supply the needs of Californians as well as exporting mercury –commonly called “quicksilver” for its wiggly properties at room temperature-- to other states across the Western USA as well as to China for the color vermillion.

Quicksilver was a crucial resource, but the mining of it lacks the romantic association with the rugged individual who starts out poor and alone in the wilderness and strikes it rich. Mercury mining is a rich man’s business from the start. Its history is entwined with the Spanish crown, The Rothschilds, the Emperor of China, and wealthy Mexican landowners who spent more time in court suing over land ownership, contracts, and corporate shares than they did at the mines.27

Figure 5: Eduoart, Alexander. Blessing of the Enriqueta Mine 1860

The 1860 oil painting Blessing of the Enriqueta Mine by Alexander Edouart (fig. 5) shows the completely different feeling of a Mercury Mine. This image can be examined for clues as to the differences between these types of mining industries.28 The mine in the painting is being inaugurated with a gathering of a diverse but financially well-off group of individuals. The clothing is in Mexican and US American style, there are women, horses, and a dog present. There is a Catholic altar and priest presiding, and the whole scene is a celebration of the harnessing of industrial power and wealth to extract still more wealth from the ground. One detail that seems oddly placed is the plume of steam coming off the condensing furnaces lower in the valley.29

Students will also look at images of the mercury refining complex with its condensing furnaces, and publicity photos of the underground mine shafts for evidence of the actual working conditions of laborers in the mine owned by the wealthy well-dressed people in the painting. Stereoscope photographs by Carleton E. Watkins are a valuable source of visual information about the growth of mercury production in this location.30

The New Almaden mines were opened in 1845 with an officially registered land claim with the Mexican government (called a diseño) which was interested in quicksilver for its own ore processing. Andres Castillero, the original owner of the mine also valued the prospect of trade with China. Cinnabar (the base material which when heated creates mercury) was used in the creation of the vermilion lacquer which was popular in Chinese decorative objects. Contracts for trade with 广州 Guangzhou were finalized in 1850 with the gift of a Chinese pagoda to the owner of the New Almaden mine. The New Almaden Mines employed Cornish and Mexican miners to work underground and, in the furnaces, but employed a substantial population of Chinese men to do the lower paid work above-ground.31

Sulphur Bank Quicksilver Mining Company is a 160-acre site which was mined between 1865 and 195732. In the early years most of the underground mine work was done by Chinese men because white laborers refused to do the dangerous and grueling work. 33 Sulphur Bank hired on average 400 Chinese men and 150 whites at any given time. The mining work underground was dangerously hot in temperature because the area has natural sulfuric hot springs. Temperatures underground were consistently close to 100 degrees Fahrenheit, so it was dangerous to work underground for more than 20 minutes at a time without fresh air. Accidents happened. On one particularly gruesome occasion a geyser was struck and all the men in that mine were boiled to death, another time, a landslide cut off the supply of cool air from the outdoors and six men were suffocated by the heat and steam below ground34.

In 1879 the California state constitution prohibited corporations with state charters from employing “any Chinese or Mongolian,” which was a problem for Sulphur Bank which relied on Chinese laborers for almost all underground work. According to the Sulphur Bank Historic Site website, Tiburcio Parrott, the president of the mine “deliberately defied the law” because he believed it to be unconstitutional. The website continues to explain that “in the test case against him, the Circuit Court on March 22, 1880, handed down a strong opinion that held the law to be in contravention of both the Burlingame Treaty and the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.”35 California was in a labor paradox, employers needed low wage immigrant laborers, but white laborers felt this was unfair competition. Lawmakers tried to appease their constituents by excluding the unwanted immigrant competition. But as soon as one group was excluded another group had to be found to replace them.36

Employers generally were happy for their workers to fight each other in a race-based rivalry for the right to do dangerous work for low pay. We now know the extremely dangerous and damaging effects of extended contact with mercury, arsenic and other metals present in their workplace. As recently as 1990, Sulphur Bank Mine was designated as a Superfund Site to be contained and managed by the EPA. A plan is still being formulated for beginning the cleanup effort. The site has millions of cubic yards of contaminated soil along with a flooded pit filled with contaminated water. The contaminated water is held back from Clear Lake by a barrier of waste rock also brought out of the mine. Contaminants in this barrier are leeching into the lake sediment which moves up the food chain. Large fish, eaten by people have high concentrations of mercury. The state of California website contains up to date advisories with guidelines on the safe amounts of fish to eat in the region. Black Bass for example are considered “Do not eat” for all individuals while the Sacramento Blackfish may be eaten in at most one serving per week for people under the age of 50. 37

The long-term impact of mercury mining on humans and the environment is associated with the fact that mercury is a neurotoxin. Once it is pried out of the ground, it leaches into the water system and poisons everything downstream. The Guadalupe River in San Jose is continuously poisoned by mine runoff from the Almaden Quicksilver mines.38 Mercury in the sediment of waterways is absorbed by plants and animals. It concentrates as it passes up the food chain making large fish dangerous for human consumption. The New Almaden watershed flows past the back of my high school and continues north to empty into San Francisco Bay. The fish of the bay and the entire Pacific Coast today carry increasing traces of mercury which has its origins in the period of the Gold Rush.

Part 4 Hydraulicking Made Everything Worse.

Gold Mining evolved from panning in rivers, to damming the rivers and mining the silt, to eventually blasting the entire mountainside with pressurized water to get at veins of gold known as the “mother lode.”39 Hydraulic lode mining was first used in 1853. Flumes of water were diverted from rivers and pressurized into hoses using gravity. The complex system required investment capital, land claims, and work crews on a large scale to effectively make a profit.

Joint-Stock Companies organized an industrial system which hired wage labor to operate in a capital intensive industry.40 Banks such as Wells Fargo made their reputation financing investments in large mining equipment, but the high cost of setting up was out of reach of most Chinese immigrants in the 1850s.41 Reliant on wage labor, Chinese men were hired by hydraulic mining corporations to do the lowest paid jobs: digging canals to direct and concentrate the water for the flumes and hoses, and removing large boulders by hand.42

In this portion of the unit students will look at photos of hydraulic mining in progress. Like the Clipper ship advertisements analyzed earlier in this unit, photos of hydraulicking were circulated to show the modern, industrial, efficiency of high-tech mining. The photos could be used to seek investment from outsiders or to publicize an individual’s successful investment in progress.43 Carleton Watkins took many stereographic photos -- are a type of double image designed to give a 3-D effect --of mining in the Sierra Nevada in the second half of his career which can be used in this portion of the unit.44 My students will look at these as they were intended--as celebrations of industrial mining, and as advertisements for investment in this type of mining across the western USA. The water jets in the images vividly leap out of the image, and the whole scene is excitingly destructive in a sublime but deeply terrifying way.

Initially Chinese miners were excluded from larger scale mining efforts because of a lack of investment capital. But by the 1870s Chinese immigrants formed their own hydraulic mining companies too. And we know they purchased the latest cutting edge “Monitor” and “Little Giant” nozzles for their hoses.45 All of these mines produced tailings (runoff) that filled the rivers downstream with sludge. This created flooding–significantly in Sacramento in 1862–and damage to farmland across Northern California.

In the 1870s conflict between mining and farming over water and rivers led to the eventual outlawing of the mining practice entirely.46 Sedimentation laced with tons of mercury impacted everyone and everything downstream.47 The Sawyer Decision (Woodruff v. North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company) curtailed the dumping of mine tailings into rivers and effectively outlawed hydraulic mining in 1884.48 Both white and Chinese miners continued to work illegally. However, much like today, the extralegal activities of an immigrant group caught the most attention from law enforcement and the media. Illegal Hydraulicking by Chinese men was punished more often.49

Some of the damaging effects of hydraulic mining can still be seen today in Dutch Flat. And evidence of the downstream impact can be seen in the dikes around the city of Sacramento built in part because of flooding caused by rivers too full of debris from the mine tailings. Students will look at images of environmental damage as they appear today in various locations such as Malakoff Hydraulic mine pit on San Juan Ridge, and Dutch Flat which can be found online easily. Several former mining locations are inside state or national parks and can be visited by tourists. These two locations are used in this unit because they are near Lake Tahoe (which people from San Jose commonly visit for vacations). Similar environmental damage was done in mining sites across the western states.

To wrap up the discussion of industrial scale gold mining, students will examine the 1871 Currier and Ives lithograph titled Gold mining in California50.It shows in miniature a kind of stylized history of mining in California, while leaving out the ugliest parts. It modifies the landscape seen in the Nahl painting from earlier in this unit, adding more houses, tree stumps, a manager in a black suit outside the house at the center of the painting, and a small version of hydraulic mining. It contains no obviously Chinese men and has no evidence of the downstream impacts of mining. It still shows a still verdant rich landscape, but it evenly sprinkled with men working. Students will analyze the extent to which this image is useful as a historical document and how we should use images like this to understand the way people want to think about the past--whether those desires reflect reality or not.

Racist Outcomes of the Mining Boom period

After relatively peaceful coexistence in the 1848-1860s, in the 1860s-80s white Californians increasingly turned against their Chinese neighbors. Eventually culminating in the Chinese Exclusion Act. After 1870 violence against Chinese people in California increased. There was an economic depression and anxiety over competition for jobs. Henry George’s words in the New York Tribune, on the opposite side of the country expresses how widespread anti-Chinese sentiments had become: “It is obvious that Chinese competition must reduce wages, and it would seem just as obvious that, to the extent which it does this, its introduction is to the interest of capital and opposed to the interests of labor.”51

While it is true that Chinese men were often willing to work for lower wages than white men, the public rhetoric of politicians used Chinese workers in the same way African Americans were used--to change the conversation from one of class and labor, to one of race. Irish immigrants who may have otherwise felt solidarity with Chinese laborers were divided from them. Comments like that of Henry George seemed to put Chinese workers on the side of employers in a conspiracy to drive down wages. This makes little sense, as those employers were arguably exploiting Chinese workers to an even greater extent than other races.52

In the 1870s, wages were depressed, and groups of Chinese workers began establishing their own successful hydraulic mining corporations.53 Resourceful Chinese men claimed and re-worked claims that white miners had abandoned and were willing to pan the tailings from industrial scale mining enterprises.54 Chinese workers were also recorded in censuses and business records as doing nearly every type of work in cities. In California half of the workers making and mending boots and shoes and crafting cigars and selling tobacco were Chinese. Chinese men were 90% of the labor hired by the Central Pacific Railroad and did dangerous work with nitroglycerine to blast open tunnels through the Sierras.55 To anyone living in California at the time, it must have seemed that Chinese men were everywhere.

Between 1850 and 1900, Chinatowns developed in cities like San Francisco, Sacramento, and San Jose. The segregated communities developed out of shared cultural ties and were led by benevolent associations such as the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association 中華會館 or “Six Companies” in San Francisco. These organizations helped organize travel for people going to and from China. They cared for the sick and arranged the return of the dead to China for proper burial. These were separate from the “fighting Tongs” or San Ho Hui /Triad Society. These more violent groups organized illegal businesses around gambling, opium, and prostitution.56 English speakers in California in the 19th century tended to conflate the two types of organization and to assign the worst assumptions to both. All Chinese people were treated with derision and suspicion. One example of this blanket discrimination is an 1870 law banning Chinese people from walking on sidewalks in San Francisco.57

Anxieties culminated in far worse violence in some places. Alongside constant low-level violence there were a few moments of explosive violence. For example, a gang of 400 men attacked a Chinese settlement in San Francisco in 1867. White men stoned and maimed the residents and burned their shanties.58 Riots known as “the Chinatown War” in Los Angeles horrifically lynched 18 Chinese residents 1871.59 In 1877 three days of anti-Chinese riots led to the burning of much of San Francisco’s Chinatown.60 Political organizers led by Denis Kearney created The Workingman’s Party of California in 1877. Their central platform was centered around the slogan “The Chinese Must Go.” Illustrations of this slogan and political images from the time can be used to show students the racist imagery and scapegoating of Chinese for all manner of labor complaints.

In 1869, the California Democratic Party officially opposed the 14th Amendment on the grounds that it would bring “untold hordes of pagan slaves” into the state to compete for jobs with white workers.61 The Chinese Exclusion Act was enacted in 1882, renewed in 1892 and again in 1902. By the twentieth century Chinese Americans were minimal participants in the labor market.

Comments: