Strange Science at the Nanoscale

We live in our own world. We are used to seeing and comprehending things that are at our scale, or approximately our size. We can change that scale by looking down at the ants and other insects on the ground, or looking up into the night sky and looking at the stars and planets above us. Looking up or down, we are still very much occupied with the scale that is most present around us. We understand and comprehend fairly easily objects and their behaviors at this scale such as an apple falling from a tree due to gravity, or the effects of a collision between two cars on a highway.

Understanding Scale of Objects

It is hard for us to comperehend the incredible distances between planets in our solar system, and the distance to other stars. Once we begin to comprehend these vast spaces it becomes clear that physics has a lot of catching up to do if we ever wish to visit any of these places in person as opposed to with a telescope. Although it is possible to understand these distances our science and technology is still firmly grounded with the scale at which we live, forcing us to launch a vehicle to Pluto that will take 9 years of flight time to get there: and Pluto is an object still within in our own solar system.

If we look downward at an ant or other insects we find lots of things to be interested in, but we still have trouble comprehending what life is like at that size scale. Looking at a lone ant carrying a portion of a leaf or a cracker that is three to five times his size and likely 10 times or greater his weight perplexes us. In our world, we have trouble carrying large items as their size makes us unstable; even the greatest human body builders cannot carry 10 times their body weight as the structure of human bones would simply crush under these increased forces. 4

Objects and matter behave differently as they get larger or smaller. Plenty of Sci-Fi has been written or filmed with either shrinking or incredibly large humans. Either change in size (larger or smaller) is usually shown as a perfectly scaled human, or insect, or animal, just at a larger or smaller scale, yet physics makes this impossible. Consider the largest and smallest humans that have lived: the changes in body shape of a human at these different scales helps to clarify this phenomena without even dealing with the gross proportions of movies or stories such as Gulliver's Travels.

A larger human has more body weight and thus more gravitational force acting upon the body: to counteract this force, the person's base (feet and legs) need to be disproportionately bigger to compensate for the increased weight, just as when a tree gets taller its trunk at the base also gets much larger creating a larger cross-sectional area at ground level. Likewise, in a smaller human, the size of legs and arms become disproportionate to the size of the chest, because the chest still must maintain all of the organs needed for the body to function.

Looking at how a human embryo grows into a fetus shows this transition of size as the body begins to become more proportionate, although even a newborn has a disproportionate head size, which is larger than the rest of the body, and it takes many years of human growth for a young child to become proportionately accurate. The larger head size is due to the importance of the functions of the brain: if you can visualize this large-headed baby and consider shrinking the body down, the head would continue to be disproportionately larger as its functions-which require a certain number of cells and, therefore, a certain volume-would still be needed.

To better understand the concepts and nature at work at the nanoscale, it is important to look at some of the primary physical characteristics at work at the different sizes and how to calculate these differences as the scale diminishes. 5

Surface to Volume Ratio

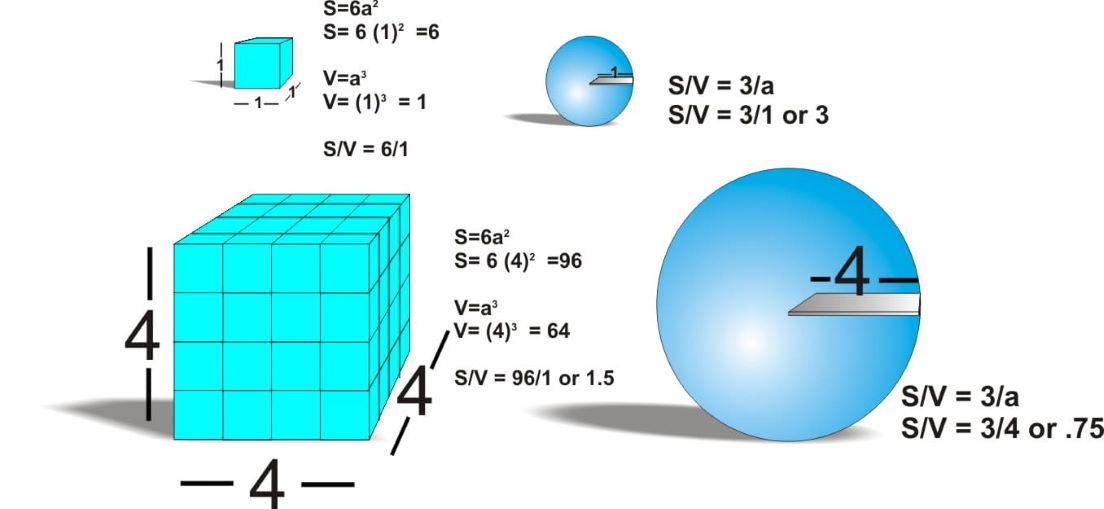

Surface to volume ratio is a concept taught in basic biology classes as a way to demonstrate the differences between multicellular and unicellular animals. This is done by showing that as an object shrinks in (a cell in this case) its surface to volume ratio increases. This concept is an important aspect of nanotechnology and should be explored further.

The surface area (S) to volume (V) ratio (S/V) is an important physical parameter. The surface area (S) is found from the formula 6(a) 2, where a is the length and width of each side. The volume (V) is found from the formula (a) 3. The surface to volume ratio can be simplified to 6/a. For example, if you have a cell that is 1 unit in length, 1 unit in width, and 1 unit in height it will have a volume of also 1 unit cubed. The ratio of S:V is 6. With a large S/V ratio, there is sufficient surface area for the cell to obtain its required intake of oxygen or any matter needed by the cell. If the cell is 4 times larger in dimension, then the surface area becomes 6(4) 2 or 96, and the volume is (4) 3 or 64. The ratio S/V is now 1.5:1. The larger cell has less surface area for the required intake of substances into the cell.

To illustrate this point using spherical objects (as nature tends to make spheres as opposed to nice neat cubes) the formulas are for surface of a sphere S= 4∏r 2 and the formula for volume is V= 4∏r 3/3 (divided by 3). This makes for a S/V ratio of 3/r for a spherical object. 6 Thus, S/V for a spherical object increases as r decreases. Figure 1 below illustrates the example for greater clarification.

figure1

Just How Small Are We Talking About?

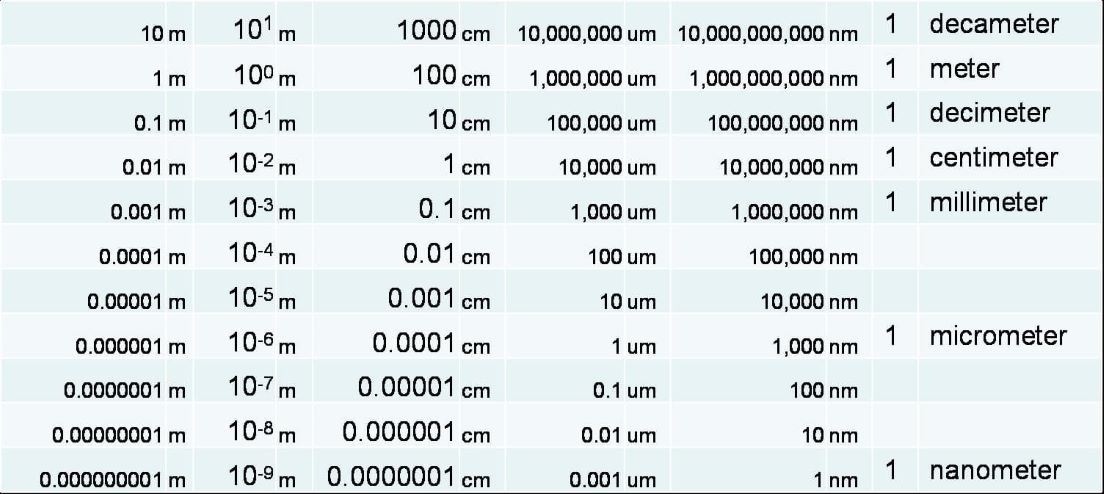

As previously stated it is difficult to comprehend the difference in scale from ours in working at the nanoscale. In a science class, student and teacher are generally working in a scale of centimeters, and may also employ the use of a meter or a millimeter. Rarely in the middle school will students be presented with the size of items smaller then this except for some brief examples in a book, such as wavelengths on the electromagnetic spectrum. In order to understand this scale it is important to look back at the units and prefixes associated with the metric system and the use of scientific notation. 7

The nanoscale is 10 -9 of the base unit of a meter. This means that in a meter there are 1 billion nanometers. A billion is already an astronomical number that is hard to comprehend, so to further illustrate the small scale at this level one can compare a nanometer to a millimeter. A millimeter still has one million nanometers in it. Suppose you asked a set of students to look at a millimeter on a ruler and asked them to place ten equidistant lines in the space between two millimeter marks. They could probably do that, but would they have the ability to scale down another ten and place 100 lines, or even 1000 lines, between the spaces of millimeter markings. The answer is an emphatic NO. Yet, even this does not illustrate the problem with understanding scale at this level, because even with these 1000 divisions, the lines are not close to nanoscale.

There are many good sites available for use in understanding scale. A site from the University of Utah (http://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/begin/cells/scale/) gives the ability to view objects in the macroscale, and continues to shrink down to objects at the nanoscale.

Scale and scientific notation are essential to teaching and understanding of objects at the nanoscale. Fig. 2 can be used to further develop the ideas of how to scale down in size for students so they can become more comfortable with the ideas. In the table the first column represents the size in meters using traditional numbering, followed by the same size using the base power of ten. Columns 2, 3, and 4 show the scale in centi, micro, and nanometers respectively. If not currently taught it is important to teach scientific notation.

Power of Ten in the Metric System

figure 2 (Courtesy Mark Saltzman 2010)

Strength to Weight or I'm Stronger than You

Strength to weight comparisons can be seen on a scale that we are comfortable with. As stated earlier, ants are capable of carrying far more weight comparable to their size than a human, which is due to the limiting effects of gravity as objects get smaller. The smaller the object gets, the greater the strength to weight ratio for that object. In the text Nanotechnology: Understanding Small Systems, the authors use scaling laws, similar to what has already been discussed with the S/V ratio. These authors disregard the overall shape of the object to provide a general understanding of the importance of size. They let length, width, and height of an object all be titled D, or characteristic dimension, of the object. It is important to point out that this will only provide a general understanding of the principal as the shape of the object would also be a key characteristic to understanding physical effects. For the purpose of better understanding the effects of scale, the definition of "D" works well.

The formulas for determining the strength to weight ratio are strength ≈ D 2 , weight ≈ D 3, so that strength/weight ≈ D 2/D 3 ≈ 1/D. In an example from the same text the authors compared a flea to an elephant giving a rough estimate of 1 m -1 for the elephant, versus about 1000 m -1 for a flea". 8 These numbers mean that a flea, for its size, is about 1000 times stronger than an elephant. This does not mean that the flea can lift 1,000 more weight than the elephant. Instead it means that the flea has much more strength per body mass than the elephant. To put it another way, if we were to look at a set of body builders in the Olympics and judge them by the strongest person would we look to see who lifts the most? To the general public they would probably say yes, but in the world of science and in accuracy this is not the case. The truth is that a smaller more dense body builder can lift more in ratio to his body weight then can a comparable larger and heavier body builder. True the larger body builder has lifted more overall weight, but in ratio of weight lifted to body mass, the smaller body builder is more successful, and thus should be considered the strongest. 9

Understanding this concept it is easy; if you continue to reduce an object eventually getting down to the nanoscale you not only increase the surface to volume ratio, but you also increase the strength to weight ratio. Thus a nanoparticle of carbon is much stronger than a much larger particle of carbon. This is one of the reasons many industries are beginning to look into the use of nanoparticles in their products.

Minimizing Effects of Gravity

Have you ever looked at small insects walking up a wall and wonder how they are able to do this? It is partly due to stickiness between their feet and the wall, but also due to the size of the object and the force of gravity on it. Pollen grains rely on riding air currents and traveling through that fluid medium: they can do this for large distances due to their size, because gravity does not bring them down to the surface of the earth. If a bird decides it is tired it can lay out its wings and glide due to expanding surface area to volume; if the same bird forgets to spread its wings gravity will take over quickly and the bird will splatter on the ground. If a flea was pushed off a two-story building it would land and hop away: gravity would not cause it to crush as it landed due to its miniscule size. If an elephant was pushed off the same building, it would be crushed under its own weight.

Using the scale of meter as the base unit, and disregarding the overall shape of the object, one can use the formula for force of gravity F g= mg and relate it to D, defined previously. In this relationship Fg ≈ D 3 as long as the units for two objects that are going to be compared remains constant. 10

Compare a rock to a particle of dust. If one has a rock that is 10cm (10 x 10 -2m) in size and a dust particle that is 10Μm (microns) or (10 x 10 -6m) in size, the dust particle is 10,000 times smaller than the rock. Using the comparison formula gravity has 10,000 3 (1 trillion) times less effect on the dust particle than the rock. These large numbers in the difference in size are pertinent as students are usually taught that all objects will fall at the same rate in a vacuum due to gravity. This concept is easy enough for students to grasp as they will be able to understand the large number and be able to understand why gravity would effect these particles with much less intensity than larger ones (especially since they can see the comparison by looking through disturbed particles either through a sunbeam, or other point source of light). If one disturbs this area you can see the dust particles flowing up and down; they do not instantly fall due to their small size, although the forces in the fluid (air pressure, and flow also come into play). This concept becomes more important for smaller objects. At the nanoscale objects are less dependent on the properties associated with gravity, instead they are more dependent on viscosity of the fluid they are in. 11

Movement of Particles

Understanding the scale of objects and the effects of scale is only one implication to being able to work and understand objects at the nanoscale. The effects can also be seen in the movement of the particles and how the particles react to each other at the molecular level through cohesion, viscosity, and attractions between particles.

Brownian Motion

Brownian Motion, named after botanist Robert Brown, attempts to explain the physics at work in the nanoscale environment. Robert Brown upon observing pollen under a microscope in the early 19 th Century noticed the pollen particles were in a constant state of motion. People attempted to explain this observation for 100 years. Finally in the early 20 th century it was explained that the motion of extremely small objects (or for that matter any object on an extremely small scale) was due to the atoms in a constant state of motion. We do not see evidence of this in our universe as we are far from the scale of individual atoms; if one was to be able to look very closely at objects such as the pollen this constant state of motion would be evident as it was for Robert Brown. 12

As the size of an object decreases its dependency and relationship to gravity also decreases. As the effects of gravity decrease the effects of viscosity on the object increases; viscosity affects the overall motion of the object and its ability to move. Viscosity is the measure of the resistance of a fluid to flow. In everyday terms one can define viscosity as how thick or thin a fluid is (meaning its overall rate of flow, thick moving slower and thin running faster). Thus in our macro-universe air and water which are the fluids we are in contact with the most are thin and thus have low viscosity (although water is much more viscous than air) making it fairly easy to move around in them, while honey or molasses are much thicker and thus have greater viscosity, making it harder to achieve the same movement through these fluids.

At the nanoscale the relative effects of viscosity in all fluids increase as the size of the object decreases. For example, if water has a viscosity of 1 to humans and a bacterium is 1/1000000 our size, then the effects of viscosity of water is 1 million or 10 6 to the bacterium compared to the human. Water is a very viscous fluid for the bacterium making it hard to move around in the fluid similar to what honey would be to us. Therefore, the bacterium in water has a similar experience to a person having to walk through fluid even thicker than honey or molasses. Although the viscosity of the water has not changed, the effects of the viscosity changes due to the size of the object. It requires a lot of energy to be able to function in a highly viscous world, thus the relationship of unicellular to multicellular is important when discussing the viscosity and energy consumption of objects at the nanoscale. 13

Reynold's Number

This relationship with small objects at this scale can be further illustrated with an explanation of the Reynold's number. This number deals with the ratio of an object's inertial forces to that of the viscous forces. As demonstrated earlier this can be done in general principal by comparison of two objects moving through the same fluid. The larger the Reynolds number of an object in motion, the greater the inertia, or the greater tendency of that object to continue moving (if no longer being propelled with energy). In contrast, the smaller the object the greater the effects of viscosity to that object, and thus that object will quickly stop moving (if the energy being used to propel the object ceases).

Consider a human swimmer in a pool. When the swimmer is completing full strokes, they move forward in the opposite direction of the force they are applying, obeying Newton's third law of motion. If this swimmer stops the strokes, they will continue moving forward or drifting forward through the fluid eventually coming to a stop due to frictional forces associated with the water; this is essentially showing a relationship to Newton's first law of motion. This swimmers Reynolds number can be calculated by taking the swimmers overall area multiplied to their velocity, and then multiplied to the fluid density, this product is then divided by the fluid viscosity number. Assume that 10 4 is the Reynold's number of the swimmer. We can compare this to a bacterium going through the same fluid, using the same rules and calculating a Reynold's number of around 10 -4. 14 In the case of the bacterium if it stopped moving its flagellum it would instantly stop moving as its inertial forces are far less than the viscosity of the fluid around it. The only motion the bacterium would continue with would be due to movements inside the fluid itself, or by being struck by another object.

Molecular Interactions

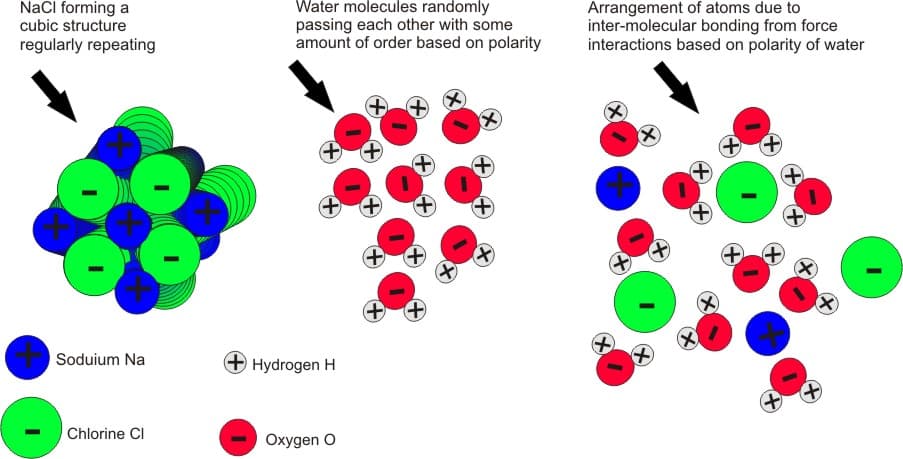

Intramolecular forces are the forces that hold compounds together. These are the cohesive bonds found in a compound either through the exchange of electrons or the sharing of electrons. Ionic or covalent bonds are strong and stable and require substantial energy to break.

Intermolecular forces are the forces found between different objects, or compounds. These can be found between compounds of an alike substance such as a teaspoon of water (H 2O), and can also be the interaction of different compounds such as a teaspoon of water with salt (NaCl) to it. The interaction of these forces is relatively weak compared to the intramolecular forces that hold a single compound together. But the forces are noticeable and important, and contribute to why we get structures on the macroscale, including ourselves. When NaCl is dissolved in H 2O the ionic bonds break down and allow the Na+ and Cl- to rearrange themselves based on the polarity of the H 2O (note: in this state the H 2O bonds remain firm and undisturbed). Although this is a general example of these interactions, it provides an excellent example as the relationship between salt and water is almost always used in teaching basic concepts of chemistry to students. For further clarification look at Figure 3. In the picture to the right you can see NaCl dissolved in H 2O; in looking at the picture note the arrangement of the molecules of water to the structures of Na+ and Cl-. This occurs due to the inter-molecular bonds between the hydrogens in water and the Cl-, and the oxygen in water and the Na+, as they have electrical bonding properties due to polarity.

(figure 3)

Understanding these properties, and that these properties exist and can be manipulated, is the cornerstone to nanotechnology and the ability to self-assemble objects.

Self Assembly

Self assembly is the ability to order objects that may not generally have order. This occurs due to the interactions between different molecules through hydrogen bonding, or use of attractive and repulsive forces. Self assembly may not always result in the correct arrangement of molecules that one is looking for, especially when attempting to generate them in a lab or industrial setting, but the relative ease at which the process works makes it cost efficient.

Self-assembly works by utilizing the fact that collections of molecules will always seek out the lowest energy level available to them. This may be in creating a bond with an adjacent molecule, or it may be a reorientation of the molecule itself to better establish intermolecular bonds such as Na+ and Cl- ions in the water. Think of a compass with its needle pointing north. If you shake the compass the needle no longer is pointing north, but once it reorients itself it again begins to point in its predestined location. This action of self assembly can even be seen at the macroscale in which we live. If you place cheerios in water or milk and give them some time to rearrange, they will begin to self assemble into a pattern of repeating hexagons. This can be done with many other products as well, bubbles for example will be attracted to each other through cohesion and thus reduce the surface area which has contact instead creating a larger structure made form these individual smaller items. For many other ideas on this look at John Pelesko's book Self Assembly.

Molecules self assemble all the time in living things. Phospholipids are molecules with two domains. One of these domains is a hydrophilic (attracted to water) and water-soluble and the other is hydrophobic (repelled from water). The hydrophilic structures are attracted to the polar water molecules found in the body while the hydrophobic sections are repelled by the water. These forces cause phospholipids to self-assemble into bilayer membranes. Phospholipids form a bilayer with the two hydrophilic sides facing opposite directions one facing outward into a water rich environment, and the other facing inward again into a water rich environment. The lipid (fat) layer represents the middle part of this membrane. This is a product of self assembly, as the individual molecules are attracted to one another through this intramolecular attraction between the hydrophilic end of the molecule and the water.

The principle of self assembly is one of the primary reasons people involved with nanotechnology have been successful at building things at such a small scale. Once it is understood how molecules will behave in different environments it is easy to use this as a method of getting molecules to join and form desired structures through this process.

Comments: