Explanation of Quantum Mechanics

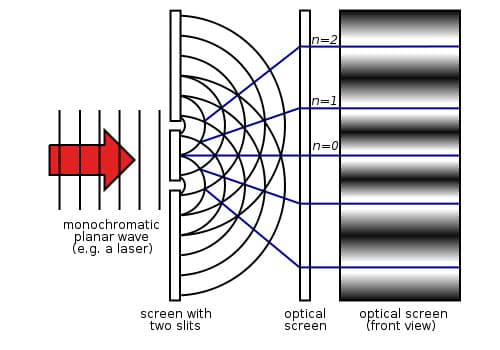

The double-slit experiment with light enables us to illustrate many of the implications of quantum mechanics and illustrates the limitations of classical mechanics. In the experiment, two slits are made in an otherwise impenetrable screen. Another screen with light sensitive detectors is set up parallel to the first screen. A light source is placed outside the first screen centered between the two slits so that the light emitted is equal distant from each slit. The light is turned on and the expectation according to classical physics and the photoelectric effect, which states that light is quantized in packets called photons, and is that the photons will go through the two slits like bullets. The photons that go through each slit will produce a pattern with greatest intensity across from the slit and diminishing in intensity away from the peak symmetrically. The pattern of the second slit will be the same. These two patterns will overlap and according to the classical model of the interaction of particles, the patterns will add linearly as I 1 + 2=I 1+I 2. However, this IS NOT what happens! Instead, the light forms an interference pattern! The pattern that is formed creates maximal intensity in the middle by constructive interference and bands of dark and light alternating out from the maximum intensity with decreasing intensity depending on whether they are in phase (constructive interference) or out of phase (destructive interference). Therefore, light, which has been shown to be made up of quantized packets of energy called photons, behaves like a WAVE! The light incident on the two slits, diffracts and interferes like a water wave.

Diagram 1

The Duality of Light

The results of this experiment are very odd indeed. But it gets stranger. Is light a particle or a wave? It turns out that we can continue with this experiment. What would happen if we close one slit at a time? It turns out that if we restrict the light from going through one slit and then the other that we get a pattern that is consistent with the model of light as a particle! There is no interference and the intensity can be represented as I 1 + 2=I 1+I 2 . We will discuss the explanation for this later, but for now it is sufficient to say that if we restrict the slit that the light can go through, it will behave like a particle.

But we are not done. There is more weirdness. What would happen if we leave both slits open but we reduce the intensity of the light that is emitted so much that only one photon is released at a time? Now, the photon is released and it goes through one of the slits and is detected when it hits the screen. From careful measurement of the detector it has been demonstrated that the light that is received always hits as a full "packet". The photons are never split into pieces. It takes a while but we allow the light to accumulate at the detector screen. Can you guess what it will look like? It turns out that even though only one photon passes through at a time, and the photons do not break apart, they still create an interference pattern! Somehow, the photons interfere with themselves and create a wave pattern consistent with I 1 + 2=I 1+I 2! Light behaves like a wave.

So, an ingenious experiment was performed. What if we place a photon detector (some type of EM radiation emitter with a short enough wavelength that it will scatter off the photon and indicate which slit the photon came through) inside the slitted screen? Now, the photon can go through either slit, but we will be able to tell which slit it came through. Will the light behave like a particle or a wave? It turns out, that no matter how low the frequency of the detector is, that simply by being detected, the photon having been detected, behaves as if one of the slits was shut. It acts like a particle and there is no interference pattern!

How can this be? Sometimes light acts like a particle and sometimes it acts like a wave. This is the duality of light. In fact, light is neither, but we do not have a better explanation. If photons are constrained, they will behave like particles. If they are allowed to pass through either slit unconstrained, their trajectory is indeterminate and then in some way they are able to pass through both! In this case, light will behave like a wave and produce a probability amplitude wave with interference!

This is not only true of light. In fact, the experiment has been done with electrons and it has been demonstrated that they also interfere and produce a probability interference wave pattern! So all particles actually have wave characteristics and are probability waves! So deterministic trajectories do not exist. If all particles have wave properties then why don't we see them and how has classical Newtonian physics survived for over 300 years? According to R. Shankar in Principles of Quantum Mechanics, if we were able to perform the double-slit experiment with 1 gram objects moving at 1 cm/s, the wavelength of each particle would be 10 -26cm! This is based on the formula Λ=2Πk=h/p. So the wavelength would be 10 -13 times smaller than the radius of the proton and for any reasonable values for the width of the slit and the distance to the screen our instruments will only detect the smooth average I 1 + 2= I 1 + I 2 . 18 So on the macroscopic scale, matter appears to behave like particles!

The explanation of quantum mechanics only explains what happens not why. "We conclude that electrons show wave-like interference in their arrival pattern despite the fact that they arrive in lumps, just like bullets. It is in this sense that we can say that quantum objects sometimes behave like a wave and sometimes behave like a particle. You may find this all rather mysterious. It is! We cannot do more to explain the magic of quantum mechanics — all we can do is describe the way quantum things behave. This description is quantum mechanics." 19 This is a crucial departure from classical mechanics. Hey and Walters attempt to explain particle-wave duality by indicating that, "It is as if the electrons start as particles at the electron gun, and finish as particles when they arrive at the detector, but the arrival pattern of electrons observed at the detector is as if they travelled like waves in between!" 20 J.L. Martin suggests that quantum reality is complex and that while some people suggest that a quantum particle is sometimes a particle and sometimes a wave that he "likes to add: 'and sometimes a clock'. However, the proper answer is 'none of these': to think of an electron as a classical particle or a classical wave, or even as some kind of paradoxical mixture of the two, is thoroughly misleading. The best description we know how to give is through the Schrodinger equation and the usual rules of quantum mechanics. It may be convenient to think of 'it' as a particle if we happen to be measuring its position r, or as a wave with wavevector k if we happen to be measuring its momentum hk-or for that matter as a clock with frequency v if we are measuring its energy hv (precisely the example of the 'atomic clock')… Is it now clear how very much the discussion depends on what we happen to be interested in at the moment?" 21 Obviously, the implications of quantum mechanics are profound and comprehensive and indeed it defies description.

The quantum wave function involves the probabilities regarding trajectories of particles. The quantum wave function also predicts the probability of arrival at different positions for an electron. The position of arrival of a single electron is thus inherently unpredictable: we can only make statements about relative probabilities of arrival for the electron. When the arrival of an electron is detected at one of the detectors, the previously spread-out probability wave function of this electron then collapses down to the region defined by this detector. "How this collapse happens is not governed by the Schrodinger equation. The collapse or 'reduction' of the wave function is the mystery of quantum mechanics." 22 In order to understand how strange this is, compare the behavior of a classical particle, which follows a classical trajectory all the way to the detector. Just before the particle arrives we could observe it heading for the chosen detector. But this is not true in quantum mechanics. Before the electron arrives at a detector we cannot say anything definite about it position or where it is headed. One of the fundamental difficulties for quantum physics is how classical quantities such as particle trajectories emerge from the probabilistic wave.

The Photoelectric Effect

The quantization of light, known as the photon, was demonstrated by the photoelectric effect experiment and explained by Einstein in 1905. When high frequency light is shone on certain metals, electrons are ejected. Classical physics could not explain why there is a cut-off frequency below which no electrons are emitted regardless of the amplitude of the light. The kinetic energy of the emitted electrons is determined by the frequency of light not the amplitude and the electrons are ejected almost instantly, if they are emitted, even if the intensity is very low. The explanation is that photons are quantized packets of energy. The photons have to have sufficient energy, based on the frequency, to overcome the atoms binding energy. When this minimum energy is supplied, the electron that is struck by the photon will be released. The amplitude of the incident light, which indicates the number of individual photons, determines how many electrons will be struck and emitted based on the equation E p h o t o n =hf (h is Planck's constant). An increase in the frequency results in kinetic energy of the ejected electron. Consequently, the concept of light behaving like a particle and a wave are not mutually exclusive! 23

The Uncertainty Principle

A fundamental principle of quantum mechanics is that we can only know the position and momentum of anything within a given amount. Stated differently, there is always uncertainty about where a particle is and its momentum which is the product of these quantities and is proportional to Planck's constant (which is extremely small, h =6.626 x 10 -34J's). The exact equation is ΔxΔp ≥ h/4Π. Consequently, the more accurately you know the position the less you know about the momentum and vice versa. This is the reason that when we measured the photons "position" in the dual-slit experiment that the wave characteristic collapsed. Based on this principle we never know what is going to happen, or when it will happen, even under a given set of conditions, only the probability of specific outcomes. 24 Uncertainty is a fundamental aspect of quantum mechanics and reality.

Schrodinger's Wave Function

There are challenging implications of Schrodinger's wave function, which indicates that matter can be explained by a wave function. This means that matter has a multitude of possible states that it can inhabit, and all of those states have a reality when the system is isolated from observation. The most familiar example is Schrodinger's cat. The thought experiment is that there is a cat in a box (with plenty of food and water) so that it cannot be observed, and it is present with a substance that emits a poisonous gas when it decays with a known half-life. The cat will die when the substance decays, but the half-life is a probabilistic event. So is the cat alive or dead in the period before we open the box? The answer is that there is a wave function of possibilities for the cat but until we open the box and make an observation, the cat is BOTH alive and dead! "Quantum mechanics seems to assert that it is in a quantum superposition. We cannot imagine how classical objects can be in a quantum superposition of two different states at once, let alone a living object like a cat. Can it really be that quantum mechanics says that it is the act of observing the cat that causes its wave function to collapse to a dead or alive cat?" 25 This wave function has been tested on the nanoscale and has proven to be true, so it is not theoretical and the implication is that quantum mechanics is continuous in its applicability… it does not just affect the atomic level, but is in fact relevant at all scales! We have been able to ignore the implications at our macroscale because the affects are "averaged out" over our billions of molecules. However, this "bizarre" reality has implications that are also useful for quantum computation and potentially for quantum computers, which would be able to take advantage of this feature of reality that there are actually a multitude of states that matter exists in that are probabilistic, until the system is "observed" and the wave function collapses into a single state.

The Many Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics

In the Copenhagen viewpoint, when an observer uses some classical measuring apparatus to make a measurement on a quantum superposition, only one of the many possible results is actually realized. The measurement process somehow mysteriously collapses all the different possible outcomes to the one observed outcome. Everett and DeWitt addressed this problem in a 'breathtakingly audacious way" by suggesting that all possibilities are realized, but each in a different copy of the universe. DeWitt indicates that each of these copies of the universe is itself constantly multiplying to allow for all possible outcomes of every measurement. In this theory there is no collapse of the wave function because the universe is replaced by a "multiverse" of parallel universes. This creative solution was dismissed by many prominent physicists. Feynman said "These are very wild speculations, and it would be little profit to keep discussing them" and Bell concluded, "if such a theory were taken seriously it would hardly be possible to take anything else seriously." 26 Quantum mechanics continues to pursue explanations of how measuring can have such a profound effect on the wavefunction nature of quantum reality.

Decoherence

A seemingly more reasonable attempt to solve the measurement problem goes by the name of "decoherence". According to this approach, quantum systems can never be totally isolated from the larger environment and the Schrodinger's equation must be applied not only to the quantum system but also to the entire coupled quantum environment. In The New Quantum Universe, the authors indicate that "Zurek claims that recent years have seen a growing consensus that it is interactions of quantum systems with the environment that randomize the phases of quantum superpositions. All we have left is an ordinary non-quantum choice between states with classical probabilities and no funny interference effects." 27 So if Hey and Walters are correct, there is a growing sense that interactions with the environment result in the appearance of particle behavior on the macroscopic world.

Quantum tunneling

Quantum 'particles' do not behave like classical objects! An electron "can tunnel through the forbidden region and appear on the other side! This 'barrier penetration' or 'quantum tunneling' is now a commonplace quantum phenomenon. It forms the basis for a number of modern electronic devices" 28, including the Scanning Tunnelling microscope. How can such tunneling occur? Based upon Heisenberg's uncertainty principle we have discussed the uncertainties in the measurements of position and momentum, but there is an equivalent relation exists between uncertainties in measurements of time and energy ΔEΔt ≈ h. According to classical mechanics we can never change the total amount of energy without violating the conservation of energy, however, in quantum mechanics, if the time uncertainty is Δt, we cannot know the energy more accurately than an uncertainty ΔE ≈ h/Δt . So in a sense, we can 'borrow' an energy Δ E to get over the barrier so long as we repay it within a time Δt ≈ h/ΔE. If the barrier is too high or wide, and based on probabilities, tunneling becomes extremely unlikely and all the electrons will be contained. The phenomenon of tunneling is a general property of wave motion and since all quantum 'particles' have wavelike properties all matter is capable of quantum tunneling.

Scanning Tunneling Microscope (STM)

Rohrer and Binnig came up with the idea of using the "vacuum tunneling" of electrons to study the surfaces of materials. The fundamental idea is very simple. According to quantum mechanics, electrons in a solid have a small, probabilistic chance of being found just outside the metal surface of the microscope "needle". The probability for this to happen is predicted to fall off rapidly with distance from the surface. Based on quantum mechanics, if we can bring a sharp, needle-like probe close to the surface, and apply an electrical voltage between it and the metal, a tunneling current will flow across the gap, even in a vacuum. Since the electron wave function falls off rapidly, the magnitude of this tunneling current is extremely sensitive to the distance between the probe and the metal. If the distance of the tip of the probe from the surface can be controlled accurately, we can use the magnitude of this current to create an image of the surface features. 29 The STM has been incredibly useful in nanotechnology engineering and has actually enabled the placement of single molecules on metallic surfaces.

Fusion in Stars Resulting from Quantum Tunneling

For decades physicists have been attempting to solve the issues related to harnessing the immense energy available in nuclear fusion. Fusion reactions are the basic process by which the stars generate their energy. This is all the more surprising because as it turns out the temperatures in stars correspond to kinetic energies much lower than the Coulomb barrier. The Coulomb barrier is the energy required to overcome the electromagnetic forces within the atom. "Fusion in the stars is only able to take place at these low temperatures because of quantum tunneling through the potential barrier. It is not an exaggeration to say that we owe our very existence to this ability of quantum particles to penetrate classically forbidden regions!" 30 It turns out that quantum tunneling is an essential process for the production of the energy source that makes life possible.

Nuclear Fission

The nucleus of the atom is made up of protons and neutrons confined within a very small space. We would expect this to be an unsustainable situation because the protons repel each with tremendous force when in such close proximity. However, the strong nuclear force dominates at very small distances allowing for the stability of the nucleus. However, if we keep adding protons and neutrons to make heavier and heavier nuclei, the range of the electric force, which is vast compared to the strong nuclear force, is enough for all the protons to repel each other. For the strong nuclear force, on the other hand, the nucleus is now so big, and the nuclear force so short ranged, that any given nucleon only feels strong attractive nuclear forces from nearby nucleons. Because of this, the weaker Coulomb repulsive force, which acts between all the protons in the nucleus, can become comparable or stronger than the attractive nuclear forces. This is the reason that stable heavy nuclei have more neutrons than protons: the excess neutrons give more attractive binding energy without any Coulomb repulsion. What happens if we start with a radioactive, large nucleus and change one of the protons into a neutron by beta decay, or eject an alpha particle? We end up with a new nucleus with fewer protons and less Coulomb repulsive energy. The new nucleus is therefore more strongly bound and more likely to be stable. Using these principles we can form the basis for the nuclear stability curve. "This process of nuclear fission can be thought of as a tunneling process, similar to the others we have described in this chapter. The energy of the fissioning nucleus can be pictured as a roller coaster potential…this shows two valleys minima of energy one of which is lower than the other. Classically, a particle at rest in the upper valley will stay there forever. Quantum mechanically, such a state is not completely stable the system has the possibility of tunneling through to the true lowest energy state. The 'false' minimum is called a 'metastable' state and fission may be imagined as a tunneling process from a state such as this." 31 Once again quantum tunneling is responsible for an understanding of the fundamental processes of physics that we normally never address in high school physics classes even when we teach nuclear processes. Therefore, quantum mechanics provides a unifying theme for divergent physical phenomenon. This is the goal of scientific explanation and a validation of the need for this unit.

Comments: