Background – The Math

Both the national mathematics and science standards reflect the need to integrate the two disciplines. The science standards speak directly about coordinating math and science programs so that students learn the necessary math skills for use in their science classes. The math standards state that students should be able to apply mathematics in contexts outside of math, and that "viewing mathematics as a whole also helps students learn that mathematics is not a set of isolated skills and arbitrary rules." 8 That's where Nanotechnology comes in! I will use content related to Nanotechnology to give students concrete examples that will help them overcome common mathematical weaknesses. At least some subset of the connections I am focusing on in this unit can be taught in nearly all of the math courses I teach. The following sections specify the key mathematical concepts I am including in this unit.

Scientific Notation

In every book and article I read about Nanotechnology, the concept of "Size and Scale" is of major importance because properties of nanoparticles are dependent on size. Unfortunately children and even many adults have difficulty with the conception of size. In my research, I learned that there is a continuum to conceptual understanding of size: ordering, grouping, number of times bigger or smaller, and absolute size. Younger children start by putting objects in relative order from small to large. The next stage in development is grouping objects of similar size, as in really big things, things we can see and maybe measure, really small things, things too small to see, etc. More sophisticated subjects in the studies specified more groups with narrower ranges of sizes. Most subjects had difficulty expressing the size of an object as a number of times bigger or smaller than another object. For example, the unit of measure to be compared could be the height of a person, and they were asked how many times longer a school bus is, or how many times smaller a ladybug is. Scale measurements were most accurate for objects close in size to human size, less accurate for very large (i.e. distance between cities) measurements, and even less accurate for very small (i.e. virus) measurements. 9 The more successful subjects explained that they estimated actual measurements of both objects and divided to calculate how many times bigger or smaller one was. The authors of the study determined that experiences of the subjects helped determine their level of success in estimating the scale factor between objects. 10 The final stage of development is estimating absolute size using conventional units such as meters, inches, etc. Again, subjects that could visualize changes in scale, or assign measurements and then multiply/divide them were most accurate in estimating absolute size. As nanoscience becomes more common, it is important for students to improve conceptual understanding of size and scale.

According to the math standards, students should develop a deeper understanding of very large and very small numbers and of various representations of them. In this unit, discussion of Nanotechnology necessitates representations of very small numbers, so scientific notation is a natural math topic to incorporate. Scientific notation is a shorthand notation for very small or large numbers. Numbers are written in the form n.pp x 10 a where n has a value between 1 – 9, a is an integer that represents the number of times needed to multiply/divide by 10 when the decimal point is after the 'units' place. The number of digits after the decimal (p's) depends on the number of significant figures (an important topic that will not be addressed in this unit). When a is greater than or equal to one, the number is greater than or equal to 10. When a is less than zero, the number is less than one, meaning we are dividing by 10 a times. The graphing calculators we use represent very large and small numbers in scientific notation using the format n.ppppp E aa, where n, p, and a represent the same as above. The exponent is shown following 'E' and is always written with two digits, using a leading zero, if appropriate. Often students ask what the 'E' means, but even more worrisome is that some ignore it, or don't look for it when answers are expected to be very small or very large! I will give instruction on scientific notation and equivalent decimals in all math classes, although students in the upper level courses may only need a 10-minute refresher while those in lower levels may require more.

Exponents

For reasons I do not understand, simplifying expressions involving exponents is a significant weakness of many of my students at all levels. Perhaps it is because we teach rules of exponents at the end of the Integrated Math 1 course and rush to finish so that students memorize rules without having a true understanding of them. Thus, when they reach the upper-level courses, their skills are weak. This unit will use the very small size of nanoparticles as a reference point, along with the concepts of scientific notation and place value in our base-10 number system, as an alternate means of learning/reinforcing exponent rules, especially the meaning of negative exponents. In addition, as I teach students to visualize the scale of nanoparticles relative to things they are familiar with, we will do repeated divisions to get from the macroscale to the nanoscale. I can demonstrate how to write the repeated division in multiple ways using both positive and negative exponents. I believe that teaching exponents in this context will have a tremendous positive impact on my students.

The following example illustrates several exponent rules. Start with a penny with a diameter of approximately 1cm. If we divide by 2, how many times must we divide until we reach a diameter less than 10 nm? To keep track of units, I would convert 1 cm to 0.01 m before starting to divide. Then, since 10 nm = 10 x 10 -9 m = 1 x 10 -8 m (this conversion could be a lesson in itself), our goal is to reach a number below 10 -8. A graphing calculator would be helpful to perform the 20 recursive divisions to reach 9.54 x 10 -9 = 0.00000000954 meters, which represents about 9.5 nm. So far, I have shown two representations of the same number (scientific notation and decimal), but it can also be written as 0.001/2 20 which shows the operations performed. Or, to demonstrate more exponent properties, it can be written as 0.01 x 2 -20 or as 0.01 x (2 -2) 10 if we only recorded every two divisions, repeated ten times to reach our goal. Of course, there are many other ways to demonstrate the meaning of exponents using the penny example. I think it also could be beneficial to describe in words what each numeric form means relative to a physical act of dividing by 2.

Geometry

Delaware math standards expect students to be able to use partitioning and formulas to find the surface area and volume of complex shapes. Because of the unique properties of nanoparticles, because of their increased surface area to volume ratio, students will have a reason to perform calculations for surface area and volume. That may sound simple, but I also want my students to understand the concept of measuring area, and not just use an algorithm to calculate it. A research article by Konstantinos Zacharos confirms what I have believed for many years – "students have difficulty in measuring area because of the emphasis on formulas without conceptual characteristics of the measurement." 11 Historically, in Euclidean Geometry, measuring area meant overlapping to compare the measured area of a surface to the area of a chosen unit. Thus, the measured area of the surface would be the quotient of the two, as in how many squares of a chosen size (i.e. 1 in by 1 in or 1 cm x 1 cm) it would take to cover the surface to be measured. The same article recommends that the tool used to perform a measurement should have the same dimensions as the object to be measured. Thus, length, having one dimension, is measured with a common tool such as a ruler. Area, having two dimensions, should be measured using 2-dimensional units such as squares or triangles to cover the surface. Volume, having three dimensions, should be measured using 3-dimensional units such as cubes to fill a space.

There is a geometry unit in our Integrated Math 2 course, but our students traditionally show a weakness on the Delaware State Test, so I would use illustrations of nanoscale materials with complex/composite shapes as warm-up problems for any other math course I teach to continue practicing these critical skills.

Logarithms

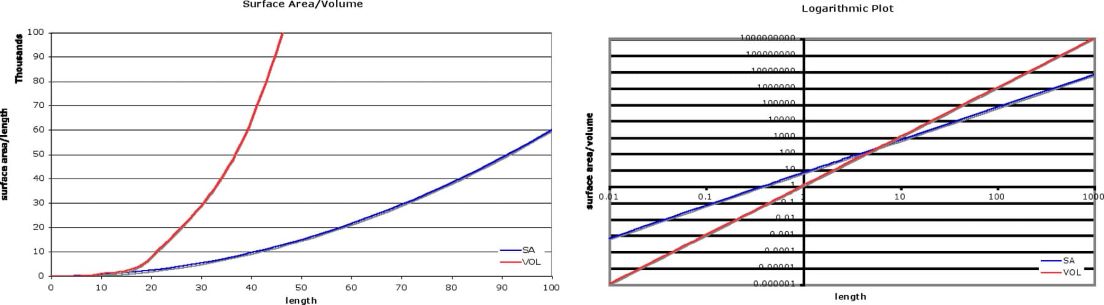

An additional math topic for precalculus students that comes from the study of nanoscale materials is logarithms. In essence, logarithms are exponents. The "log" of a number is the exponent that a base must be raised to in order to get the number. Logarithms and exponential functions are inverses of each other. The use of logarithms reduces multiplication to addition, and division to subtraction by applying exponent rules. Graphs that use logarithmic scales change a curved graph to a linear one (Figure 3). As an example, if students plot the surface area and volume measurements for varying scale factors (i.e. side length of a cube) the graphs are curves (SA L 2, V L 3), whereas on a logarithmic plot the surface area increases linearly with a slope of 2, and the volume

ul

In a

Figure 3 – Surface Area and Volume of a Cube

increases with a slope of 3. In a typical Precalculus course, logarithm concepts are taught as skills with drills to practice them. Relating the skills to what students have learned about nanoscale particles will add interest to the concept. Creating graphs with logarithmic scales and adding images or labels of common objects for sizes represented on the graph and discussing the difference in scale will, again, reinforce students' number sense while keeping the ideas of Nanotechnology fresh in their minds.

Fibonacci Series

The Fibonacci series is an integer pattern that has intrigued my students in previous classes whenever it came up. It is not part of any curriculum in my school, but I am including it here as an extra for students that may be interested in further exploration. The series begins with the integers 0, 1 and continues by adding the two previous numbers: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21…. The Fibonacci series has ties to nature as described in John Pelesko's book on self-assembly. It matches the breeding pattern of rabbits and the spirals in pineapples and pinecones and sunflowers. Counting the number of clockwise spirals and the number of counter-clockwise spirals, the pair of numbers are consecutive numbers in the Fibonacci series (unless outside factors interfere with growth). "They arise because of the relationship among the Fibonacci sequence, the golden mean, and optimal packing." 12 The golden mean, or golden ratio, has been studied since Euclid wrote about it in his book Elements in 303 BCE. It is an irrational number, , defined by (a+b)/a = a/b where a + b is the total length of a line segment and a is the longer of the two segments. Many ancient buildings, including the Parthenon, were built according to the proportion of golden ratio because it is aesthetically pleasing. 13 As each number in the Fibonacci series is divided by the previous number, the ratio approaches the golden ratio, approximately 1.618. 14 In nature, flowers often grow in spirals following the pattern of 360 * (golden ratio) because it is the most efficient use of space and allows optimal access to sunlight. 15 The connection to Nanotechnology cited in Pelesko's book is a self-assembly process which coats silver spheres with a layer of silicon oxide in either the spiral pattern described, or another natural (hexagonal) configuration.

Formulas

If I were collaborating with a science teacher to teach this unit, I would have him/her provide context and appropriate formulas related to Nanotechnology. I could include these already-familiar formulas with a gentle reminder of why/how they used them in science to practice solving, evaluating, and manipulating equations full of variables. However, I will not include formulas at this time.

Concentration

Concentration is another topic that I could potentially include. As we discuss size and scale, and students' conceptual understanding of very small things improves, it may be appropriate to review calculations for extremely low concentrations that would be expressed in parts per million (ppm) or parts per billion (ppb). In the past I found it helpful to refer to percent as parts per hundred, so that the calculations of ppm and ppb are set up in the same way, but with larger denominators.

Comments: