Background and Teaching Strategies

Translating Expressions

Students love a single number answer, so the idea of working with expressions is always a challenge. Expressions need to be taught with an emphasis on the values and meaning in order for students to be able to work with them accurately and effectively in the Algebra classroom. Though most Algebra classes are set up to focus on algebraic expressions, it is important to help students make connections to what they already know and understand. The study, done by Subramaniam and Banerjee, asked students to find the perimeter of a figure with k sides, each with a length of 5. There were "near zero" correct responses. However when the students were given the task of finding the perimeter for a shape with 10 sides, each having a length of 4, over 60% got the correct answer. 2

An expression is recipe for a mathematical calculation. An introduction to expressions should begin with conversations about relationships between different values. I will begin with low numbers and simple ideas that allow all students to easily grasp the idea of the expression and to learn the standard way of writing basic expressions. Challenging manipulations can be used once students are clear on the components of the expression. As suggested by Roger Howe, "I advocate a gradual approach, steadily upping the ante, and checking for mastery at each stage."

A question to begin the process, "Ana has three more pencils than Carmen, how many does Ana have?" Most students will recognize the question cannot be answered, though some will attempt a solution. Those that jump for the solution are the ones who suffer from the need to always find a simplified answer. They will be a focus group later when I talk about the challenges of changing the way students think about the equal sign.

The majority will realize that they are unable to answer the question because there is not enough information. This question gives them a minute to ponder the idea of an "unknown amount." Before taking it to the variable expression, it is helpful to give students some amounts for Carmen. First Carmen has 1 pencil, then 5 pencils, then 10… allowing students to respond with how many pencils Ana must have. This dialogue helps students recognize the fact that each time I give them an amount for Carmen they are able to add 3 and find the amount for Ana. Numerical expressions are often clear and second nature. It is important to make the expression concrete by writing it down and connecting each part of the expression to the given definition.

Many students lose meaning and context with expressions when variables are introduced. In order to make a smooth transition I will write "Number of Carmen's Pencils + 3", as the expression. While the discussion seems very elementary for 8 th grade, the purpose is to avoid the disconnect that happens for most students with the variable and operation. Now is a good time to re-introduce the variable. I say, "re-introduce" because students have learned about variables in previous grades, however my concern is they have not been given a conceptual understanding and therefore don't use it with a clear awareness of its purpose. In the article, "Arithmetic to Algebra" Roger Howe makes a key point about variables. The unit must always be included in the definition along with the words "number of". 3 The variable is not identifying an item, but rather the number of items in the given problem. This "good mathematical hygiene," as Roger would say, prevents problems later on for many algebra students when they begin to work with systems of equations.

Once students can interpret and use the basic expressions, I will work with progressively more complex expressions, using a similar strategy. The original expression was "Ana has three more pencils than Carmen, how many pencils does Ana have?" The algebraic expression being p + 3, where p represents the number of pencils Carmen has. The next expression, Max has 3 times as many pencils as Carmen. I will repeat the same amounts for Carmen as I used in the previous example. Carmen has 1 pencil, 5 pencils, and 10 pencils. Students will be asked to determine how many pencils Max has. They will also have to decide what operation is being used to calculate the number of pencils Max has. Writing the arithmetic problems down is helpful, especially when making a connection to the algebraic expression. To create a visual example we will write down the arithmetic. Carmen has one pencil, how many does Max have? 1 x 3 = 3. Carmen has 5 pencils, how many does Max have? 5 x 3 = 15. Carmen has 10 pencils, how many does Max have? 10 x 3 = 30. So our new expression is "Number of Carmen's Pencils" x 3. Again being clear that our variable p does not represent pencils rather the number of pencils, we can write the second expression as 3p.

The next expression is a little tricky. Sam has 3 times as many pencils as Ana. The tricky part is, that we want to express the number of pencils that Sam has in terms of the number of pencils Carmen has. The increase in complexity here is a pivotal point. Students begin to disconnect from the original p + 3. It is crucial that the students again identify what the variable is representing as well as what the entire expression represents. Ideally the white board will be organized with each set of expressions. Therefore, we can go back and look at the previous expression for Ana, which is represented by p + 3. This moment is a great opportunity to identify students who track correctly with the expressions. I ask students, "If Sam has 3 times as many pencils as Ana, and Ana has 5 pencils, how many pencils does Sam have?" Students easily answer 15. The next question, "If we know how many pencils Carmen has, can we figure our how many pencils Sam has?" After students have had a moment to think the question through, I suggest that Carmen has 6 pencils, how many does Sam have? The three most common answers are 18 (because the student multiplied 6 x 3), 21 (because the student multiplied 6 x 3 and then added 3), and then of course the correct answer 27 (because the student added 6 + 3 and then multiplied the sum by 3). As students share their answers I also have them share the process. To clear up the confusion we begin with Carmen having 6 pencils and work our way through Ana, Max, and Sam. At this point we discuss the importance of parentheses. Students need to know that, when we put an expression in parentheses, we mean for the result of the whole expression inside to be multiplied by the number outside. Parentheses mean, "treat whatever is inside as a single number." The final expression for Sam will be 3(p + 3).

Even though students understand how to calculate the amount of pencils for Sam, some make a mistake and write the expression 3p + 3. Rather than just dropping this suggestion (if it is made), it is important to take this expression and define it in context of the situation. If 3p + 3 were the algebraic expression, then the verbal expression would have to be something like, Sam has three times as many pencils as Ana, and three more besides. Students need to be re-directed when they make an error, but it is equally important that they are aware of why a solution is not correct. Discussion about how Sam has 3 times as many pencils as Ana and therefore 3 must multiply to the whole quantity of p + 3 will reinforce the idea of parentheses. The precision with vocabulary here is also important. Students should be able to speak a verbal expression that represents 3(p + 3) using vocabulary such as "three times the quantity of p plus 3" or "three times the sum of p plus 3."

To continue practicing the precision of vocabulary students will take turns creating expressions and telling them to the class. The class writes them down and then compares to check for accuracy. I will give the students a few examples to get them started. See appendix A.

Simplifying Expressions

Students will learn to simplify complex expressions using the rules of arithmetic. The Associative, Commutative, and Distributive rules are not new to Algebra students. However, even the high achieving students see the properties as a vocabulary issue rather than rules to be internalized and applied. In her article Teaching Arithmetic and Algebraic Expressions, Subramaniam states, "Rules must be connected to concepts in order to enhance their learning and retention. Since concepts occur as referents in the statement of rules, conceptual misunderstanding may lead to incorrect learning of rules. Pupils need to be flexible in their application of rules and conceptual understanding mediates such flexibility." 4

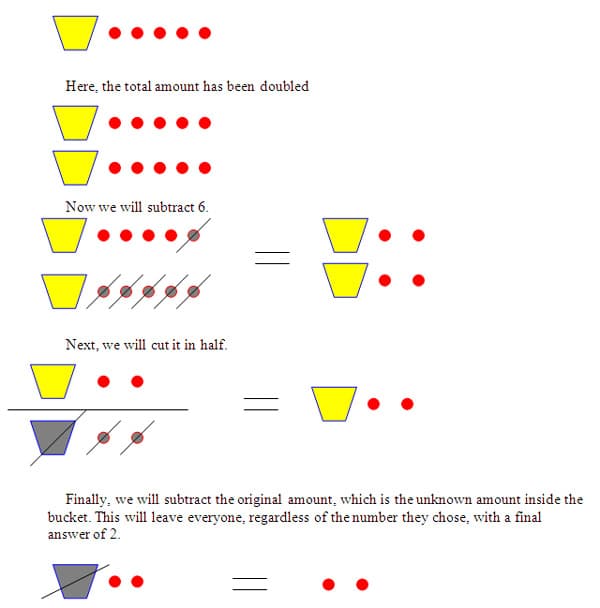

As an introduction to simplifying expressions I will begin this section with some number tricks. Students will fold a piece of notebook paper into three columns. They will do the work for each trick in its own column. This will allow them to go back and analyze their calculations to see if they can determine how the number trick works. Once we go through the number tricks and look at the visual diagram, students will go back and re-write expressions for the following three number tricks.

Trick 1: Choose a number between 1 and 10. Add 5. Double that. Subtract 6. Cut it in half. Subtract your original number.

I will then have students compare answers with a neighbor. Everyone should have a result of 2. I will give students two minutes to discuss why this happened with their group.

Trick 2: Choose a number between 1 and 10. Add 12. Multiply by 2. Subtract 18. Add the opposite of your original number. Subtract 6.

Everyone should now be at the original number they chose. Again I will have students discuss this with their group. I will encourage students to discuss why this trick is different from the previous trick.

Trick 3: Choose a number between 1 and 10. Add 7. Multiply by 4. Subtract 14. Divide by 2. Subtract the original number.

This trick will allow me to tell the student the number they chose by subtracting 7 from their final answer. Again students will be given some time to look at and discuss the three tricks. I will encourage students to share the different numbers they chose as well as the steps they took with each direction. It is my hope that a few students will look at the different papers within their group and begin to see the similarities in the process and work. Each group will be given the opportunity to share why the tricks worked.

Thinkmath.edc.org offers a simple visual explanation. I've included the drawing they would use to represent the first number trick.

In the bucket is the unknown amount that was chosen, along with 5 additional dots.

Once students understand the visual model, we will go back and replace the pictures with variables and numbers. I will have students look at the connection between the "unknown bucket" and a variable. Students will then work in groups to draw both visual models and write the expressions for the first three number tricks we did. Students will see how helpful variables and expressions are for explaining these number tricks. Students should then be given time to make up their own number tricks as well as the explanations for why the trick works.

Rules of Arithmetic

Arithmetic Rules will be an important focus of this unit. We will look first at the rules and how they apply to addition and then go back through to see how they apply to multiplication.

The Associative Rule of Addition allows us to group numbers in any order, (a + b) + c = a + (b + c). However, I find most students identify any expression with parentheses as the Associative Property regardless of the grouping. In order to avoid this misconception I want to give students scenarios to group the numbers in different ways but to see that the solution remains the same. What I find interesting is the concept seems elementary in a problem like Jay received $5 from his dad and $3 from his mom. How much money does he have? A couple hours later Jay's sister gave him $4. How much does he have now? Then to reword the same problem to Jay received $5 from his dad. Jay went into the kitchen and his mom gave him $3 and his sister gave him $4. How much money did Jay receive from his mom and sister? How much money does Jay have altogether? This type of discussion is obvious to most students. I feel it is important at this stage of clear numerical thinking to make the connection to the Associative Property using variables. Once students grasp the concept, the difficulty level will be raised. Students will be asked to find all the different ways to group the addends. Students will begin with 3, then 4, then 5 addends. They will work to come up with all the ways the addends can be grouped. Students will then extend this to writing word problems. They will keep the information the same in each problem, however write an explanation for the different groupings. This will be extremely challenging for many students especially the English Language Learners. In order to scaffold the activity, I will work with small groups to write the first problem. Then we will orally discuss how we would change the problem in order to change the grouping only. It will be important to check with struggling groups each step of the way, to be sure they are understanding both the concept of grouping as well as how to explain it in word format. I have never done an activity like this, but it makes me smile as I think about it. Students will struggle, but enjoy the challenge of it. I look forward to seeing what they come up with.

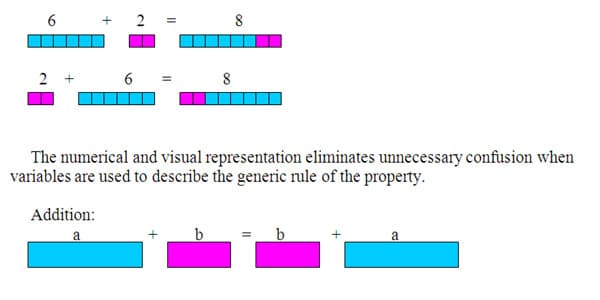

The Commutative Rule of Addition allows for numbers to be added in any order. For example 6 + 2 = 2 + 6.

Most students are comfortable with this straightforward explanation. However as expressions expand there is some difficulty with the movement of terms so as to collect like terms. I will address this difficulty later when I talk about collecting like terms.

Since the Associative and Commutative Rules of Addition are fairly obvious, I plan to deal with them first. Once students are clear on the addition rules we will move to the rules of multiplication.

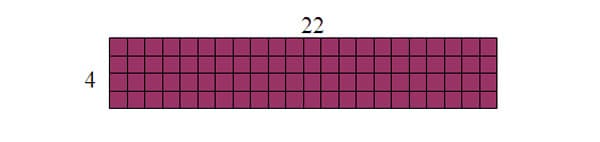

The Commutative Rule of Multiplication allows numbers to be multiplied in any order. It states that ab = ba just as 6 x 2 = 2 x 6. An array model is a clear way to show students this rule. Using graph paper to draw a box that is 2 units long by 6 units wide and then flipping the same rectangle so it is now 6 units long by 2 units wide. To help students generalize their understanding of this rule I will ask them if this same thing would be true if the numbers were 5 and 8, 9 and 4, 32 and 14, 25 and 25, x and 4? As students begin to realize it doesn't matter what whole numbers we use they will see it is a matter of multiplying the number of rows by the number of columns or the number of columns by the number of rows, regardless of what those values are. A couple of examples using larger numbers is important as well as drawing the rectangles using variable expressions to represent length and width. It is also a good idea to acknowledge different types of units. For example, 6 CDs at $8 each and 8 CDs at $6 each both cost $48. 8 pizzas with 10 slices and 10 pizzas with 8 slices both have 80 slices (however, size of slice might come into discussion here.)

The Associative Rule of Multiplication is a little tricky. To demonstrate I will use a shoebox. It is important to stop here and review the formula for volume. To clearly show the Associative Rule I will explain to students that the volume of the box is the area of its base times the height of the box. So the question becomes, will the volume change if we put the shoebox on a different side, giving it a different base? Once students agree that it doesn't change, we will look at the measurements and different ways we can group the factors.

The Distributive Rule is a unique rule, which connects addition and multiplication. This rule is a favorite among 8 th grade students. I find they prefer using the rule when variables are involved. Something like 4(3x +5) causes less of an uproar than 4(3 + 5). The tragic frustration stems from the fact that students have no depth in their understanding of the distributive property. They have never learned to break numbers apart (like 8 x 42 is equal to 8(40 + 2)). Therefore they don't see the connection between the order of operations and the distributive property. They recognize the need for order of operations in a problem like 4(3 + 5) but miss the connection that 4(8) is equivalent to 4(3) + 4(5) because 12 + 20 = 32. Time will need to be spent developing mental math skills to solve a problem like (8)(63) by breaking it up into 8(60 + 3). This will be a great opportunity to work with number manipulations and see the Rules of Arithmetic at work. It is crucial to take the time to break down their desire to compartmentalize everything they learn. Students must realize these rules are used because they work – always! The Distributive Rule is a phenomenal tool for calculation and we really don't teach students how to use it.

Since the Distributive Rule can be so valuable for mental calculations, I will use some mental math to introduce it in the classroom. I always place a high emphasis on the importance of showing work. Introducing an activity that requires mental math will spark interest in some students as well as anxiety in others. It is also an opportunity to see which students have some background with the Distributive Rule. I will ask students to mentally solve the following problems: 8 x 32, 4 x 39, and 12 x 26. Students will be given an opportunity to share the strategies they used to compute the problems mentally. This will be the first time I have done an activity like this, so I look forward to hearing the different approaches.

I anticipate that some students will have used the distributive property to expand the numbers, for example 8 x 32 will be broken down into 8 x 30 + 8 x 2. This observation will allow us to look at other problems and see why it works. Students will also discuss why we choose to break 8 x 32 into 8 x 30 + 8 x 2. Again this addresses the importance of students learning these rules conceptually so that they can be flexible and confident in the way they solve them. 8 x 30 + 8 x 2 is thought to be the easiest way to mentally solve the problem 8 x 32, however 8 x 15 + 8 x 17 and 8 x 25 + 8 x 7 are other forms of the distributive property, all of them creating equivalent expressions.

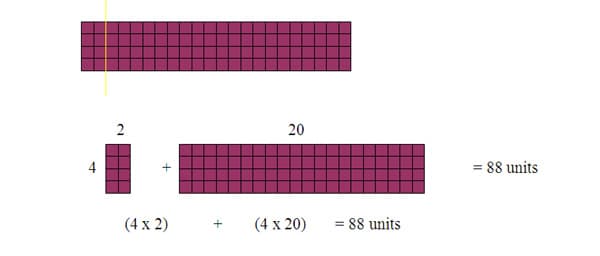

After the mental math and work breaking apart the multiplications problems, students will move to working with area figures to deepen their conceptual understanding of breaking these numbers apart. Take a problem like 4 x 22, I will show students a rectangle with a length of 22 and a width of 4.

I will ask students to find the area of the given rectangle by using the formula Area = length x width. Once students calculate the area of the rectangle to be 88, I will have a student draw a line to cut the rectangle into two rectangles. Which might create a figure like the one below.

Now rather than 4 x 22 representing the area we have broken the rectangle into 4 x 2 and 4 x 20. Students will then see visually the area of the rectangle has not changed, even though it has been broken apart. This idea can be extended into two-digit by two-digit multiplication as well. For example we will use a rectangle with a length of 47 and a width of 22. Now, the rectangle will be cut both horizontally and vertically and will create four new rectangles. Though many cuts could be made, to begin, we will cut the rectangle's width of 22 into 20 and 2. The rectangles length will then be cut into 40 and 7. The area of each new rectangle will be added together to get the total area of the original rectangle. So, 22 x 47 = 20 x 40 + 2 x 40 + 7 x 20 + 7 x 2 = 1,034.

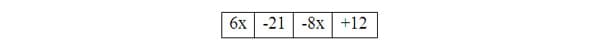

Solid understanding of the Distributive Rule is necessary to combine like terms with consistency and confidence. Students will be able to distribute numbers or variables into the parentheses and then use the commutative and associative rules to re-order terms. Students struggle with being able to identify a complete term as well as keep the correct sign with it. Once students simplify using the distributive property they will box each term with its sign in the expression. The students begin with an expression, 3(2x – 7) – 8x + 12. The students should start by distributing the 3 into the parentheses, so the new equivalent expression will be 6x + (– 21) + (– 8x) + 12. At this point, students box the terms so they can easily identify each individual term.

Students will then use the commutative property to re-order the terms. The re-ordered expression will be written 6x + (– 8x) + (– 21) + 12. In the past I have allowed students to identify and combine like terms, however doing this prevents them from seeing the distributive rule still at work. One of my favorite Roger Howe quotes is, "Shortcuts are the privilege of the expert." Therefore, students will need to show the distributive property as the next step. Taking the new expression and grouping together the like terms so (6x – 8x) – 21 + 12, and then recognizing that the x can be pulled out of both terms x(6 – 8) -21 + 12. Students continue to simplify x(-2) – 21 + 12 = -2x – 21 + 12, and finally the simplest form of the expression -2x – 9.

Once students learn the properties and how to use them to simplify the expressions they will need time to practice the manipulations. Students will practice by setting up a two-column paper. On the left, they will write the expression and work the computational part of the problem. On the right, they will list the property that is being used.

Example: Simplify 5(3x -7) + 4x

The expression in simplest form is 19x – 35.

The manipulations of the expressions will make a direct connection to the concept of equivalent expressions. Students apply the properties to the expressions in order to identify which expressions are equivalent. Students will need to be able to explain why expressions are equivalent by identifying which property they are using.

Comments: